Association Between Obesity and Diastolic Dysfunction in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Featured is the presentation entitled "Association Between Obesity and Diastolic Dysfunction in AF Patients" by Prashanthan Sanders, MBBS, PhD, FHRS, from Session 5 at Western AF 2025.

Transcripts

Thank you, Nassir, for having me back again at this meeting. I always enjoy it.

So, in terms of obesity, we've all come to accept that this is one of the highest attributable risks for developing AF. There are a number of mechanisms by which obesity leads to AF, but I also want to highlight the fact that there are a number of coexisting conditions that occur in people who have obesity, which give rise to AF on their own. We also know that there are significant clinical implications to patients by the obese state, and this we've come to accept.

We’re much less aware of HFpEF or diastolic dysfunction in AF, and this has been alluded to in Carolyn Lam's talk. What we know is that in the HFpEF population, the prevalence of AF can be as high as 50%. Similarly, in the AF population, this is documented at around 20%. This is a bidirectional relationship—they can lead to each other. But as was mentioned in the earlier talk, they share several common risk factors that have been outlined here, that may make these twins rather than being that of a vicious circle as outlined by Carolyn Lam. One of these risk factors is obesity, and given its frequency in our community, this is going to be important for us.

One of the problems in terms of determining how many of our AF patients have HFpEF is that it's really hard to diagnose HFpEF unless someone is in pulmonary edema and you can then work out if they have a normal left ventricular function. There are a couple of scoring systems, none of which are perfect. This is work from Johnathan Ariyaratnam and colleagues where they looked at invasive studies during the time of AF ablation and compared it to what each of these scoring systems do, and they don't do that well. They're modest at best in terms of the diagnosis. It highlights that we may be underestimating what we see in our AF ablation population. So, one of the things that Jonathan did as part of his PhD program is conduct invasive studies in consecutive patients undergoing AF ablation, putting in arterial pressures, left atrial pressures, and also right atrial pressures. We took people who did not have clinical HFpEF and we evaluated them in terms of left atrial pressure more than 15 milligrams of mercury. We also infused saline into the left atrium looking at how compliant the atrium was, how it enlarged on echo together with what the pressures do. We found that there's a group who have HFpEF and there's a group that has early HFpEF that is on the way and doesn't respond so well in terms of compliance of the atria. These were the results of that study. It shows that 75% or so of our patients coming for AF ablation now have HFpEF physiology, despite the fact they have not presented with clinical HFpEF features as yet. So, this highlights the enormity of the problem that we are dealing with, and I think this is one of the missed risk factors that we've had in terms of our management.

What's more in this series is that if you look at AF symptoms, the patients in yellow and red who have a degree of HFpEF actually have more symptoms of AF ablation. When we do CPAP testing, their VO2 max is a lot less. When we look at quality of life, they have worse quality of life as a result of having this coexisting condition. If we try to look at mechanism in terms of the cardiomyopathy, the compliance of the atria—that is how much it dilates for the pressure—is reduced in those with HFpEF physiology as is on echo, their reservoir strain function.

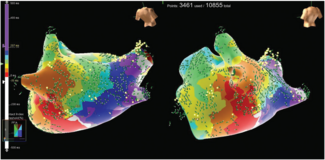

If we look at the EP parameters, these atria are much sicker in those with early HFpEF and HFpEF. They have lower voltages and lower conduction velocity within the atria. So, we're dealing with a sicker state in patients who demonstrate this sort of HFpEF physiology.

Where does obesity fit into this? If we look at our population in terms of those who are obese and non-obese, what we see is that the greater proportion of patients with obesity actually have HFpEF physiology despite not presenting with HFpEF. If we look at their atrial pressures, the obese individual has a higher left atrial pressure. This is interesting, because if we look at the right atrial pressure compared to the left atrial pressure, the red lines are showing the obese individual. The right atrial pressure seems to be much higher. Now, one of the things about the right atrial pressure is it's an indication of pericardial constraint of the heart. So, we are seeing a greater amount of that, and I'll show you more of this as we go in the next few slides.

It's not surprising that obesity leads to HFpEF physiology. We've shown in our animal studies a greater degree of interstitial fibrosis, greater epicardial fat, and fat infiltration that all can lead to this sort of physiology.

In the clinical situation, the Mayo Clinic Group have shown that LV end-diastolic pressure and LA pressures are higher. We've shown pericardial fat to be more excessive, and in areas adjacent to the pericardial fat, there's more low-voltage regions.

Now, one of the things that obesity does is there is an increased blood volume in patients who are overweight and obese, and this has been well-documented in the literature. Concurrent with this, and perhaps not surprising, if we look at cardiac size in our series, it's bigger in obese individuals. So, this kind of gives you an idea. Your pericardium can only fit so much, but your cardiac size is much, much bigger. Obesity leads to increased blood volume, increased left atrial pressures, and a phenotype of HFpEF, and this has been documented in a number of series. This is using pulmonary capillary wedge pressures in this publication.

What we also did was look at the cardiac volume to the right atrial pressure and then the cardiac volume to the right atrial versus left atrial pressure ratio. The red dots show the obese individual. Again, you can see this is pushed upwards. There is a right atrial pressure increase that seems to be correlating to a degree with the cardiac volume. In fact, there have been previous publications that also show that this constraint leads to flattening of the septum, because the pressure within the right ventricle is quite high as a result, so this is not a new phenomenon.

In terms of adipose tissue, we know it leads to a cardiomyopathy. We know it leads to the electrophysiological changes through paracrine effects, and this is a huge area of study. If we look at epicardial fat in terms of what happens to the right atrial pressures, again, we see that the obese individual shown here in red has higher pressures when they have more epicardial fat, that it's taking up more space within that pericardial sac. So, this is an additional feature why obese individuals have more HFpEF physiology.

So, what do we have? In the obese state, we know that you can get left atrial remodeling and a cardiomyopathy from that. We also know that blood volume increases LA pressures, end-diastolic pressures, and also left ventricular hypertrophy. There is also pericardial restraint and there's this interdependence of the ventricles because they both have to contract against each other. We know LA dilatation leads to a substrate change. We know in pericardial fat contributes to both of these, and all of this physiology gives rise to this concept of AF and HFpEF through these mechanisms.

Now, there is good news in this. This is a study from R. Mahajan and colleagues where they studied obese sheep and got the sheep to lose weight. In the top line, we see normalization of electrical properties. In the middle, we see fibrosis that occurred due to obesity going away. In the bottom line, we see pericardial fat infiltration reducing with this. Pressures in the heart are the first thing that reduces in this model of weight loss, so I think we have some hope in this.

So, HFpEF is highly prevalent in obesity, contributes by LA substrate change, plasma expansion, cardiac enlargement, epicardial adipose tissue, and elevated pressures within the heart. I want to highlight that in the recent guidelines we introduced the management of risk factors; on the steps of these pillars was the HEAD2 TOES concept of looking at risk factors where we preemptively put H as heart failure management. We may need to start thinking about this for our AF patients, that HFpEF may be an important thing for us to manage upstream. Thank you.

The transcripts have been edited for clarity and length.