Photobiomodulation in Wounds of Individuals With Diabetes: A Nonrandomized Pilot Study

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Photobiomodulation (PBM) has shown promising results in accelerating wound healing and modulating inflammation. Objective. To evaluate the feasibility of PBM therapy in treating lower limb wounds in people with diabetes. Materials and Methods. This was a 12-week prospective, pilot, multicenter, nonrandomized clinical trial. The 25 participants were divided into the intervention group (IG), in which a laser was applied once a week (660 nm, 100 mW power, 2 J/cm2, continuous wave, visible beam) and hydrogel was applied daily, and the control group, in which hydrogel was applied daily. Participants older than 18 years with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and with lower limb wounds smaller than 100 cm² were included. Participants with lupus, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome were excluded. Comparisons between the groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test, and comparisons between different time points were performed using the Friedman test. The Fisher exact test was used to assess associations between groups and qualitative variables. Results. No statistically significant difference in wound area was observed when comparing the 4 time points evaluated between groups. However, there was a significant difference when comparing the 4 time points in the IG (P < .0083). No significant difference between groups was observed in the expression of the cytokines investigated. Conclusion. Application of PBM at an intensity of 2 J/cm² once a week did not produce measurable changes in the cytokine gene expression. However, significant reduction in wound area and an improvement in tissue repair were observed in patients treated with PBM.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is both characterized by hyperglycemia and is associated with a chronic inflammatory response by an imbalance in cytokine production, which leads to tissue deterioration.1,2 Among the cytokines involved in this process, interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), interleukin 10 (IL-10), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α),3 and transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)4 are particularly notable. Due to the imbalance in cytokine production, in individuals with DM wound healing tends to stall in the inflammatory phase, the first phase of the healing process, making progression to the subsequent phases difficult.5

Supportive therapies are necessary in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds, and the search for accessible and low-cost interventions is constant. Among these therapies is photobiomodulation (PBM), which involves wound irradiation with light of different wavelengths ranging between the visible spectrum and infrared, using lasers, light-emitting diodes, and other devices.

PBM has 3 different mechanisms of action described to date. The first involves the absorption of light by the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase, which is located in the electron transport chain in mitochondria. This enzyme converts light into adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reactive oxygen species (ROS),6 which contribute to the reduction of the inflammatory process and, in turn, facilitate wound healing.7 The second mechanism occurs through opsins, transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 (TRPV1) channels, and aryl hydrocarbon receptors.8 This modulates the passage of essential ions, such as calcium, protons, and Na+ /K+. The third mechanism is related to the activation of TGF-β1 by the ROS produced, which promotes cellular regeneration and wound healing.8

Several studies have highlighted the benefits of PBM, including modulation of the inflammatory process, cytokine levels, and oxidative stress.9-12 Furthermore, a review that included 3 clinical trials showed a reduction in wound area in individuals who received this treatment.13 Another study demonstrated that PBM has a stimulating effect on fibroblasts in human skin, increasing cellular proliferation and viability.14

PBM has shown promising results in accelerating wound healing and modulating inflammation. However, compared with other therapies, evidence regarding the efficacy of PBM is still lacking. Considering the high epidemiological impact of DM and of the associated hard-to-heal wounds, it is essential to obtain robust scientific evidence on the feasibility of PBM as a therapy. This evidence is crucial for adjusting treatment protocols and parameters before conducting larger clinical trials that would require significant time and resources.

Pilot multicenter studies have emerged as indispensable tools for identifying and validating effective therapies for diabetic foot ulcer (DFU). These studies enable the evaluation of interventions in diverse populations and clinical settings, enhancing the generalizability of results and the precision of adjustments for protocol standardization.

PBM has demonstrated promising results in accelerating wound healing and modulating inflammation; however, more consistent evidence is needed to compare its efficacy with conventional therapies. There is a vast literature demonstrating the safety of PBM in the treatment of DFU, with no reports of adverse events, despite different protocols and treatment durations.15-18 In these studies, PBM was applied up to twice a week for 12 weeks. One review demonstrated that studies investigating the dose effect of PBM at various wavelengths (range, 405 nm-850 nm), fluences (range, 0.5 J/cm²-10 J/cm²), and power densities (10 nW/cm² and 40 nW/cm²) found that the best effects on tissue repair occurred at a power density of 10 mW/cm² and a fluence range of 0.5 J/cm² to 2 J/cm²; additionally, the wavelength was bimodal at 425 nm and 660 nm.17

Given these findings, the objective of the current pilot study was to assess the feasibility of PBM therapy in treating lower limb wounds in people with DM. The primary outcome was the evolution of the wound; this outcome was analyzed based on reduction in wound area in centimeters squared, as determined by measuring the length and width of the wound. The secondary outcome was the ulcer characteristics, including the type of wound bed tissue, depth, edges, granulation tissue, necrotic tissue type and amount, exudate type and amount, skin color, edema, and induration surrounding the wound, as well as epithelialization.

The development of this pilot study is an essential step in guiding future research and contributing to the development of more accessible and efficient therapies for treating wounds in individuals with DM.

Materials and Methods

This was a 12-week prospective, pilot, multicenter, nonrandomized clinical trial designed to assess the feasibility of PBM therapy in treating lower limb wounds in people with DM.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the State University of Campinas (No. 43782721.4.1001.5404), Campinas, Brazil, in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was registered at the Brazilian Registry of Clinical Trials (No. RBR-9vv5rsw, available at https://ensaiosclinicos.gov.br/rg/RBR-9vv5rsw) and followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) guidelines.19

Data collection

Data collection was conducted at an outpatient facility at the university hospital of the State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil, and at another university hospital in the metropolitan region of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from April 2022 through April 2024.

Participants

Individuals aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of type 1 or 2 DM who presented with a DFU smaller than 100 cm² were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included participants with lupus, pyoderma gangrenosum, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels greater than 12%. Discontinuation criteria included allergic reactions or failure to attend more than 2 consecutive appointments.

Recruitment and allocation of participants

Participants were allocated using sequential sampling. Those who met the eligibility criteria were alternately assigned to the intervention group (IG) or the control group (CG), until all participants had been assigned to a group. Any participant with 2 or more wounds received the same therapy for all wounds, which explains the higher number of participants in the IG.

The IG visited the outpatient facility once a week for wound cleansing, debridement if necessary, and the PBM application protocol, which consisted of laser irradiation (660 nm, 100 mW power, 2 J/cm2, continuous wave, visible beam, once a week) followed by application of a carboxymethylcellulose hydrogel.20 The distance between the laser application spots was 1 cm², ensuring that the same energy was irradiated per centimeter squared on the wound edges and bed.21 Participants and health care professionals wore protective glasses during the procedure.

The CG attended the outpatient facility for wound cleansing, debridement if necessary, and application of a carboxymethylcellulose hydrogel. All participants in both groups were treated with carboxymethylcellulose hydrogel and were instructed to change the dressing daily by applying this product to the wound bed and covering it with sterile gauze.

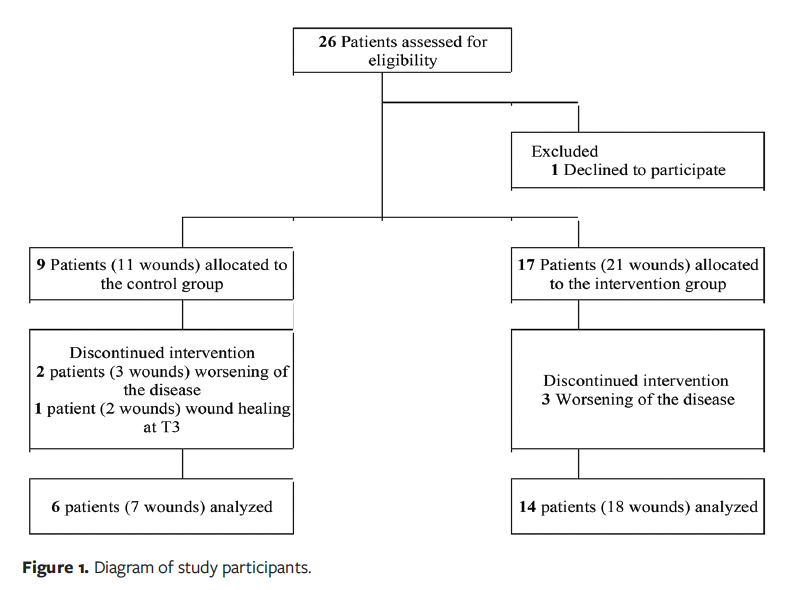

A total of 26 participants were eligible to participate; however, 1 patient dropped out, so 25 participants were included. Of these, 9 participants were allocated to the CG; 2 participants had 2 wounds each, for a total of 11 wounds. A total of 17 participants were allocated to the IG; 4 of them had 2 wounds, for a total of 21 wounds in this group. During the study, 3 participants (with 5 wounds) dropped out of the CG: 2 due to worsening of DM and 1 due to wound healing at 3 weeks. In the IG, 3 participants dropped out due to worsening DM. Thus, 6 participants with 7 wounds were included in the CG, and 14 participants with 18 wounds were included in the IG (Figure 1).

Patient demographics and wound evaluation

Sociodemographic data were collected and documented at the baseline visit (T0). Additionally, at that visit wounds were evaluated for amputation risk using the Wound, Ischemia, and Foot Infection (WIfI) classification.22 Wounds were assessed at T0 and at 4 weeks (T4), 8 weeks (T8), and 12 weeks (T12) using the Brazilian version of the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool (BWAT).23 The BWAT was used to evaluate wounds based on size, depth, edges, undermining, necrotic tissue type, necrotic tissue amount, exudate type, exudate amount, skin color surrounding the wound, peripheral tissue edema and induration, granulation tissue, and epithelialization. The final BWAT score ranges from 13 to 65, with higher scores indicating worse wound status.

Wounds were photographed weekly from a distance of 20 cm, next to a ruler, using a digital camera (PowerShot SX400 IS; Canon) without flash. Wound areas were calculated using the open-source software ImageJ version 1.49 (National Institutes of Health), with the scale set for each measurement based on the ruler in the captured image. All technical aspects of image acquisition were followed according to the recommendations of Spear.24

Wound fluid collection and cytokines gene expression analysis

The wound fluid was collected using a sterile cervical brush25 by gently rubbing the brush on the wound bed at T0, T4, T8, and T12. After collection, the biological material was immersed in TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in microtubes and stored at −20°C until RNA extraction for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) technique.

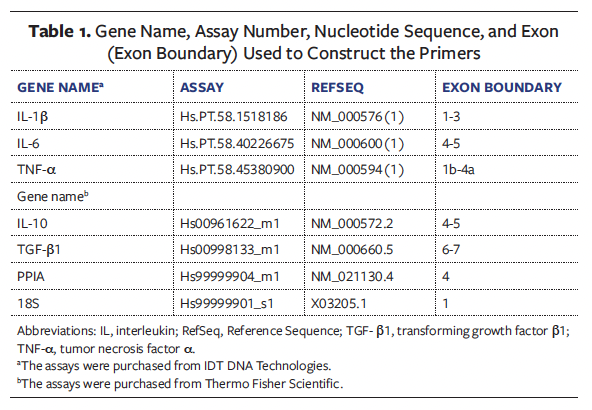

RNA extraction and gene expression analysis of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and TGF-β1 (Table 1) were performed according to Barbieri et al.25 PPIA and 18S were used as housekeeping genes. The results used were 2^-dct, a formula used to calculate the relative expression of a target gene compared to a reference gene (housekeeping gene) in PCR experiments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Incorporated) and SPSS version 23 (IBM Corporation) software. Sociodemographic and clinical characterization of participants were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The Mann-Whitney test26 was used to compare groups with regard to sociodemographic variables, wound area, and BWAT scores at each time point. The Friedman test26 was used to compare time points within each group regarding wound area and BWAT scores. The application of the Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test occurred only after confirming that the Friedman test had shown significant results. The Fisher exact test27 was used to assess associations between groups and qualitative variables. The Bonferroni correction was applied to the significance level in these comparisons.28 The alpha level set for these analyses was .0083. Data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characterization of participants

A total of 20 participants were included in this study. In the CG, 6 participants with a total of 7 wounds were included, and the wounds were treated with hydrogel alone. In the IG, 14 participants with a total of 18 wounds were included, and the wounds were treated with PBM and hydrogel.

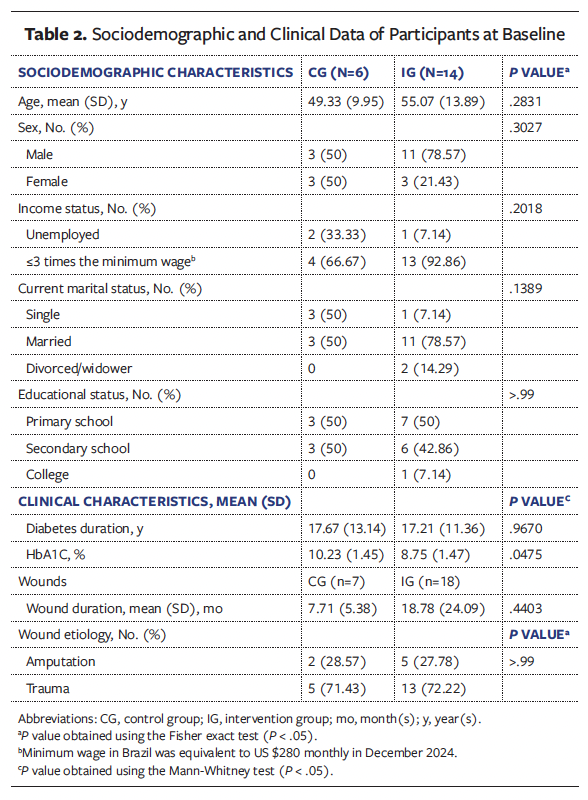

In the CG, the participants’ mean age was 49.33 years, 50% were male and 50% were female (n = 3 for both; patient sex was self-reported), and 50% (n = 3) were single (Table 2). Most of the participants had an income of up to 3 minimum Brazilian wages (US$280 monthly). Half of the participants had completed primary school (ie, elementary education). The mean duration of DM was 17.67 years, and the mean HbA1c level was 10.23%. The mean wound duration at baseline (T0) was 7.71 months, and 5 wounds were caused by trauma.

In the IG, the participants’ mean age was 55.07 years, 79% (n = 11) were male and 21% (n = 3) were female, and 79% (n = 11) were married. Most participants (92.86% [n = 13]) had an income of up to 3 minimum Brazilian wages (US$280 monthly). Half of the participants had completed primary school. The mean duration of DM was 17.21 years, and the mean HbA1c level was 8.75%. The mean wound duration at baseline (T0) was 18.78 months, and 13 wounds were caused by trauma.

All wounds were located on the lower limb. Five individuals had 2 wounds.

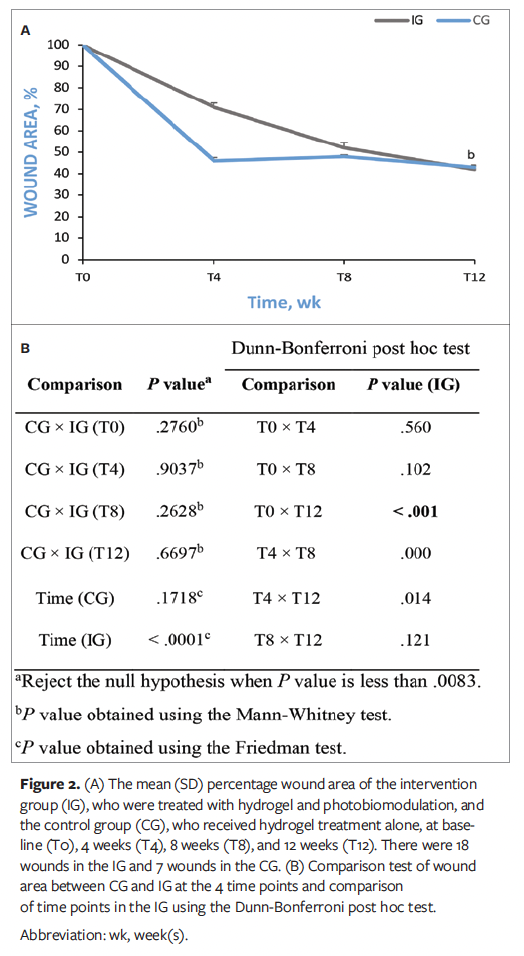

Wound area

There was no statistically significant difference between groups regarding wound area at the 4 time points analyzed (T0, T4, T8, and T12). In the CG, there was no significant difference in wound area at these time points. However, the IG showed a significant difference in wound area when comparing the 4 time points analyzed (P < .0083) (Figure 2A). Based on this result, a Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test was conducted to determine at which time points statistically significant differences occurred, and it was found that the statistically significant difference in wound area occurred between T0 and T12 in the IG (P < .001) (Figure 2B).

WIfI classification

Based on the WIfI classification,22 in the CG 6 wounds were classified as stage 1 (small or superficial without gangrene) and 2 were classified as stage 2 (deep ulcers with exposed bone, joint, or tendon with or without gangrene limited to digits).

In the ischemic evaluation, all wounds were classified as stage 0, with no signs of ischemia. In the infection evaluation, 6 wounds were classified as stage 0, with no signs of infection, and 1 was classified as stage 1, indicating the presence of mild local infection. In infection stage 1, only the skin and subcutaneous tissue are involved, with erythema greater than 0.5 cm and less than or equal to 2 cm around the ulcer.

In the IG, 16 wounds were classified as stage 1, and 2 wounds were classified as stage 2. In the ischemic evaluation, 15 wounds were classified as stage 0, and 3 were classified as stage 1. In the infection evaluation, 6 wounds were classified as stage 0, and 1 wound was classified as stage 1.

BWAT–Brazilian version

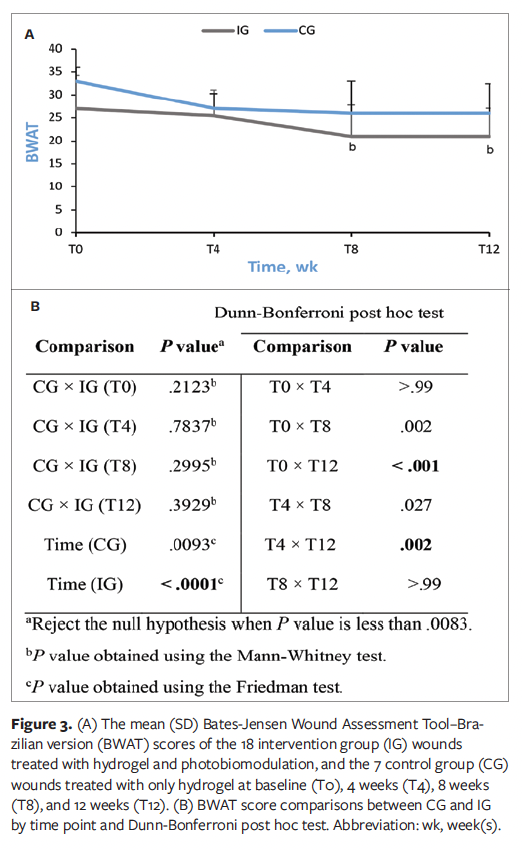

The wounds were analyzed based on size, edges, exudate type, peripheral tissue edema, granulation tissue, and epithelialization. In the CG, there were no statistically significant differences in the mean BWAT scale scores at any time point analyzed. However, in the IG, significant differences were found between the time points (P < .0083) (Figure 3A). Consequently, the Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test was performed and showed statistically significant differences between T0 and T8 (P = .002), T0 and T12 (P < .001), and T4 and T12 (P = .002) in the IG (Figure 3B).

Cytokine gene expression

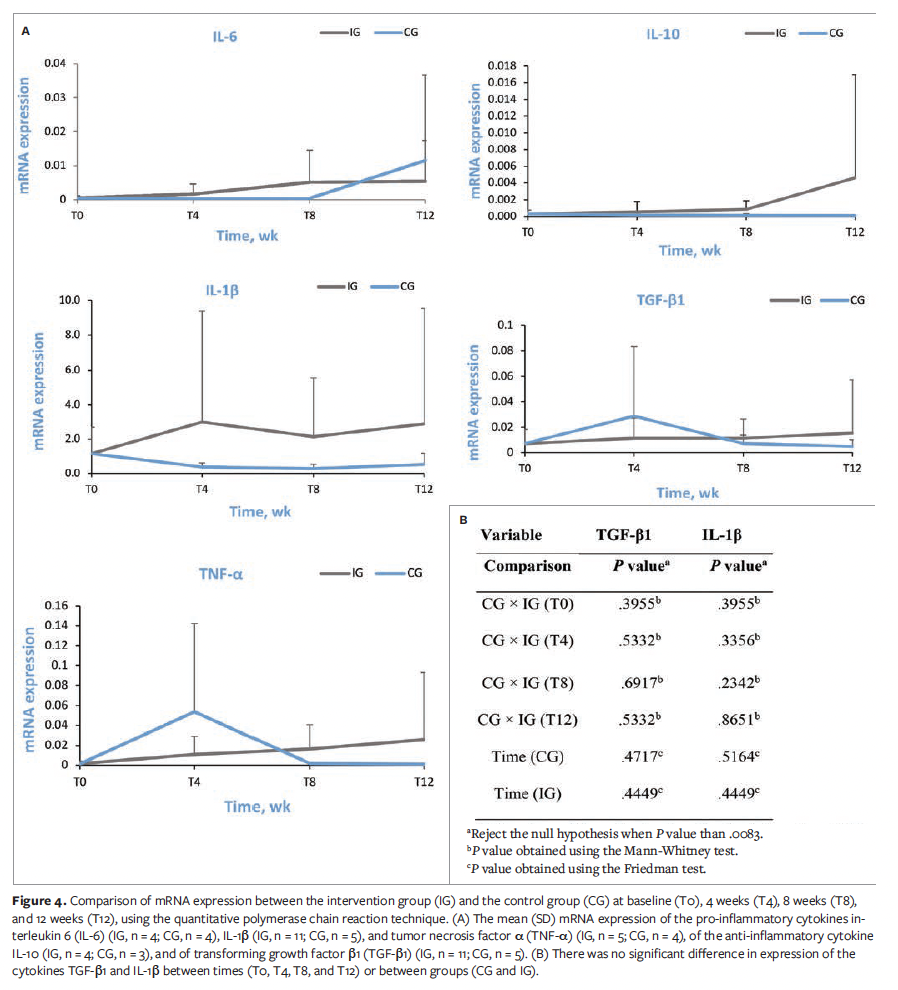

Figure 4A shows the comparison of mRNA expression between the IG and the CG at T0, T4, T8, and T12, using the qPCR technique. In this figure, “n” represents the number of wounds.

Comparison tests were carried out only on the cytokines TGF-β1 and IL-1β because a small number of samples showed the expression of genes in the cytokines IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α. Expression of the cytokines TGF-β1 and IL-1β showed no significant difference between time points (T0, T4, T8, and T12) or between groups (CG and IG) (Figure 4B).

Discussion

This pilot, multicenter, nonrandomized clinical trial provided proof of concept by investigating the use of PBM in DFUs, analyzing wound healing in terms of wound area and modulation of inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, the study assessed the feasibility of conducting a randomized clinical trial.

Patients with DM have recurrent, hard-to-heal wounds, and due to the clinical aspects of the disease, wound healing is delayed. The literature describes risk factors for the occurrence of wounds in these patients, such as male biological sex, advanced age, less schooling, and income.29

In the present study, the sociodemographic characterization of the participants shows a predominance of adult males, a mean age of 53.8 years for males, and a predominance of primary school education. Regarding the clinical aspects of the disease, the participants in the present study had a mean HbA1c level of 9.49%, which is higher than the recommended value (5.7%).30 This mean level in the present study reflects poor glycemic control, thus contributing to the risk of ulceration and making healing more difficult. Glycemic management is a crucial aspect of controlling DM because persistently high blood sugar levels increase the risk of wound development and amputation.31

According to the literature, there is a close relationship between glucose levels and the progression of DM complications such as DFUs.32 Studies demonstrate a positive correlation between wound healing and good glycemic control.32,33 The HbA1c level serves as a crucial clinical predictor of wound healing, indicating that for every 1% increase in HbA1c, there is a corresponding decrease in healing of approximately 0.028 cm2.32,33 Therefore, the participants included in the present study were subject to strict monitoring of glycemic control at the service where the study was conducted.

In the current study, the wounds were classified as superficial, with no signs of ischemia or infection, based on the WIfI system. Wound evaluation was performed using the Brazilian version of the BWAT, and based on the parameters of this tool, it was noted that the IG showed an improvement in wound healing, which indicates that PBM is effective in modulating wound healing by accelerating the wound closure time and improving the wound bed tissue. Furthermore, the findings indicate a reduction in wound area in the IG, reinforcing PBM’s potential as an adjuvant therapy for wound healing.

However, the nonsignificant difference in wound area at T4 in the CG compared with the IG may have been influenced by wound duration. Wound duration in months was shorter in the CG than in the IG. Chronic wounds are defined as wounds that stagnate in the inflammatory phase or do not undergo an orderly process to restore the anatomical and functional integrity of the tissue, or both.34 However, it is not well established in the literature when a wound becomes chronic; therefore, these wounds with a shorter duration in the current study may have progressed more quickly at T4 than those in the IG with a longer duration.

Technologies in the health field have been advancing in order to make the general population’s life better. One such technology is PBM, which has been used in the management of DFUs and has shown promising results, such as wound area reduction.35-37

Studies have shown beneficial aspects of PBM. For example, a double-masked randomized clinical trial that enrolled 23 patients with DM demonstrated a reduction in wound area after using PBM (685 nm, 10 J/cm²).37 A different double-masked randomized clinical trial that used PBM (660 nm and 890 nm, twice a week) in the management of DFUs showed an improvement in granulation tissue.38 These results reinforce the potential of PBM as a therapeutic intervention for the healing of DFUs.

The qPCR analysis did not show the expression of some of the investigated genes, making it impossible to compare the expression levels of IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α between groups due to the small number of participants. The expression of TGF-β1 and IL-1β was compared between the groups, and no significant differences were observed across time points or between groups, despite the appropriate amount of RNA being extracted.

These findings suggest that, although PBM has effects on wound healing, its effect on cytokine gene expression was not prominent in the present study. This outcome may be attributed to the small sample size.

The wound healing process is a highly coordinated and intricate sequence of events involving numerous growth factors, such as TGF-β1, which plays a role in inflammation, angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, extracellular matrix remodeling, cellular growth, and differentiation.39

Although the present study did not find significant differences between the analyzed groups, a literature review indicates that PBM contributes to cellular viability, mitochondrial ATP activity, and the integrity of fibroblast membranes in human skin.40 Another important factor to consider is IL-1β, a pro-inflammatory cytokine that stimulates the Th1 immune response and IL-6 production.41 In the present study, the researchers did not observe the expression of this cytokine, a finding similar to that of a study that investigated IL-1β expression in saliva from individuals with oral mucositis treated with PBM.42

The findings of the present study do not support the expert opinion that using PBM at a wavelength of 660 nm and an intensity of 2 J/cm² can improve wound healing in individuals with DM over a 12-week treatment period.

Limitations

This study has limitations, including the inability to mask the groups, which is justified by the nature of the phenomenon. Additionally, this was a nonrandomized pilot study with a small sample size, which is typical for studies of this type. Another limitation is the difference in HbA1c values between the groups; patients in the CG had higher HbA1c values compared with patients in the IG, which may have contributed to the tissue repair in the IG.

Conclusion

It is worth noting that wound management is not restricted to local therapies but rather, it also requires attention to many other factors, such as the appropriate use of medications, glycemic control, sleep quality, and nutrition. Therefore, future studies consisting of randomized clinical trials, with sample size calculation and well-defined protocols for power density, fluence range, and wavelength, could be useful. However, it is important to state that the protocol model presented herein should not be reused because it did not show any effect at any level for PBM. Additionally, the follow-up period for the wound should be extended to assess recurrence.

Author & Publication Information

Authors: Beatriz Barbieri Bortolozo, MSc1,2; Amanda Ramiro Gomes da Silva, MSc3; Thais Paulino Prado, PhD1,2; Bianca Campos Oliveira, PhD3; Joseane Morari, PhD2; Flávia Cristina Zanchetta, PhD1,2; Eliana Pereira Araújo, PhD1,2; Beatriz Guitton Renaud Baptista de Oliveira, PhD3; Bruna Maiara Ferreira Barreto Pires, PhD3; Priscila Peruzzo Apolinario, PhD1; and Maria Helena Melo Lima, PhD1,2

Affiliations: 1School of Nursing, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil; 2Laboratory of Cell Signaling, Obesity and Comorbidities Research Center, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil; 3Aurora of Afonso Costa School of Nursing, Fluminense Federal University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the State University of Campinas (No. 43782721.4.1001.5404). All participants provided written informed consent.

Correspondence: Maria Helena Melo Lima, PhD; R. Tessália Vieira de Camargo, 126 - Cidade Universitária, Campinas - SP, Brazil, 13083-887; melolima@unicamp.br

Manuscript Accepted: August 11, 2025

References

1. Alvim R de O, Dias FAL, Oliveira CM de, et al. Prevalence of peripheral artery disease and associated risk factors in a Brazilian rural population: the Baependi Heart Study. International Journal of Cardiovascular Sciences. 2018;31(4):405-413. doi:10.5935/2359-4802.20180031

2. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes−2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S135–151. doi:10.2337/dc20-S011

3. Schaper NC. Lessons from Eurodiale. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28 Suppl 1:21–26. doi:10.1002/dmrr.2266

4. Sen CK, Roy S. Redox signals in wound healing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780(11):1348–1361. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.01.006

5. Guo S, DiPietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89(3):219–229. doi:10.1177/0022034509359125

6. Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. The definition and measurement of antioxidants in biological systems. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18(1):125–126. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(95)91457-3

7. Anders JJ, Lanzafame RJ, Arany PR. Low-level light/laser therapy versus photobiomodulation therapy. Photomed Laser Surg. 2015;33(4):183–184. doi:10.1089/pho.2015.9848

8. Mosca RC, Ong AA, Albasha O, Bass K, Arany P. Photobiomodulation therapy for wound care: a potent, noninvasive, photoceutical approach. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32(4):157-167. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000553600.97572.d2

9. Kumar Rajendran N, George BP, Chandran R, Tynga IM, Houreld N, Abrahamse H. The influence of light on reactive oxygen species and NF-кB in disease progression. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019;8(12):640. doi:10.3390/antiox8120640

10. Fernandes KPS, Costa Souza NH, Mesquita-Ferrari RA, et al. Photobiomodulation with 660-nm and 780-nm laser on activated J774 macrophage-like cells: effect on M1 inflammatory markers. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2015;153:344–351. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2015.10.015

11. Salehpour F, Farajdokht F, Cassano P, et al. Near-infrared photobiomodulation combined with coenzyme Q10 for depression in a mouse model of restraint stress: reduction in oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis. Brain Res Bull. 2019;144:213–222. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.10.010

12. Pigatto GR, Silva CS, Parizotto NA. Photobiomodulation therapy reduces acute pain and inflammation in mice. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019;196:111513. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111513

13. Santos CMD, da Rocha RB, Hazine FA, Cardoso VS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of low-level laser therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2021;20(3):198-207. doi:10.1177/1534734620914439

14. Ayuk SM, Houreld NN, Abrahamse H. Effect of 660 nm visible red light on cell proliferation and viability in diabetic models in vitro under stressed conditions. Lasers Med Sci. 2018;33(5):1085–1093. doi:10.1007/s10103-017-2432-2

15. Kajagar BM, Godhi AS, Pandit A, Khatri S. Efficacy of low level laser therapy on wound healing in patients with chronic diabetic foot ulcers-a randomised control trial. Indian J Surg. 2012;74(5):359-363. doi:10.1007/s12262-011-0393-4

16. Barolet D, Roberge CJ, Auger FA, Boucher A, Germain L. Regulation of skin collagen metabolism in vitro using a pulsed 660 nm LED light source: clinical correlation with a single-blinded study. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(12):2751-2759. doi:10.1038/jid.2009.186

17. Mgwenya TN, Abrahamse H, Houreld NN. Photobiomodulation studies on diabetic wound healing: an insight into the inflammatory pathway in diabetic wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2025;33(1):e13239. doi:10.1111/wrr.13239

18. Miranda MB, Alves RF, da Rocha RB, Cardoso VS. Effects and parameterization of low-level laser therapy in diabetic ulcers: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-umbrella. Lasers Med Sci. 2025;40(1):109. doi:10.1007/s10103-025-04366-2

19. Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N; the TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):361–366. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.3.361

20. Deutsch G, Oliveira BC, Pessanha FS, Cassiano KM, de Oliveira, BGRB, de Castilho SR. Cost of treatment and reduction achieved by chronic ulcer in diabetic patients - a comparison between hydrogel and human recombinant epidermal growth factor. International Journal of Development Research. 2020;10:41286-41290. doi:10.37118/ijdr.20158.10.2020

21. Rennert R, Golinko M, Kaplan D, Flattau A, Brem B. Standardization of wound photography using the Wound Electronic Medical Record. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2009;22(1):32-38. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000343718.30567.cb

22. Mills Sr JL, Conte MS, Armstrong DG, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Threatened Limb Classification System: risk stratification based on wound, ischemia, and foot infection (WIfI). J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(1):220-234.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.003

23. Alves DF dos S, Almeida AO de, Silva JLG, Morais FI, Dantas SRPE, Alexandre NMC. Translation and adaptation of the Bates-Jensen wound assessment tool for the Brazilian culture. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem. 2015;24(3):826–833. doi:10.1590/0104-07072015001990014

24. Spear M. Wound photography: considerations and recommendations. Plast Surg Nurs. 2011;31(2):82–83. doi:10.1097/PSN.0b013e31821baa7e

25. Barbieri B, Silva A, Morari J, et al. Wound fluid sampling methods and analysis of cytokine mRNA expression in ulcers from patients with diabetes mellitus. Regen Ther. 2024;26:425–431. doi:10.1016/j.reth.2024.06.016

26. Pagano M, Gauvreau K, Mattie H. Principles of Biostatistics. 3rd ed. Chapman & Hall; 2022.

27. Mehta CR, Patel NR. A network algorithm for performing Fisher’s exact test in rxc contingency tables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78(382):427-434. doi:10.2307/2288652

28. Johnson RA, Wichern DW. The Bonferroni Method of multiple comparison. In: Johnson RA, Wichern DW, eds. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Prentice-Hall International Inc; 1992:197-199.

29. Schmidt MI, Hoffmann JF, de Fátima Sander Diniz M, et al. High prevalence of diabetes and intermediate hyperglycemia - the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6:123. doi:10.1186/1758-5996-6-123

30. McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJM, Selvin E, Hicks CW. Etiology, epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2022;46(1):209–221. doi:10.2337/dci22-0043

31. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 12. Retinopathy, neuropathy, and foot care: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(1 Suppl 1):S252–S265. doi:10.2337/dc25-S012

32. Ajjan RA. How can we realize the clinical benefits of continuous glucose monitoring? Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19(S2):S27-S36. doi:10.1089/dia.2017.0021

33. Markuson M, Hanson D, Anderson J, et al. The relationship between hemoglobin A(1c) values and healing time for lower extremity ulcers in individuals with diabetes. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2009;22(8):365-372. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000358639.45784.cd

34. Lazarus GS, Cooper DM, Knighton DR, Margolis DJ, Pecoraro RE, Rodeheaver G, et al. Definitions and guidelines for assessment of wounds and evaluation of healing. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(4):489-493.

35. Woodruff LD, Bounkeo JM, Brannon WM, et al. The efficacy of laser therapy in wound repair: a meta-analysis of the literature. Photomed Laser Surg. 2004;22(3):241–247. doi:10.1089/1549541041438623

36. Kaviani A, Djavid GE, Ataie-Fashtami L, et al. A randomized clinical trial on the effect of low-level laser therapy on chronic diabetic foot wound healing: a preliminary report. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29(2):109–114. doi:10.1089/pho.2009.2680

37. Landau Z, Migdal M, Lipovsky A, Lubart R. Visible light-induced healing of diabetic or venous foot ulcers: a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29(6):399–404. doi:10.1089/pho.2010.2858

38. Minatel DG, Frade MAC, França SC, Enwemeka CS. Phototherapy promotes healing of chronic diabetic leg ulcers that failed to respond to other therapies. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41(6):433–441. doi:10.1002/lsm.20789

39. Penn JW, Grobbelaar AO, Rolfe KJ. The role of the TGF-β family in wound healing, burns and scarring: a review. Int J Burns Trauma. 2019;2(1):18–28.

40. Peplow PV, Chung TY, Ryan B, Baxter GD. Laser photobiomodulation of gene expression and release of growth factors and cytokines from cells in culture: a review of human and animal studies. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29(5):285-304. doi:10.1089/pho.2010.2846

41. Ferrero-Miliani L, Nielsen OH, Andersen PS, Girardin SE. Chronic inflammation: importance of NOD2 and NALP3 in interleukin-1β generation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147(2):227–235. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03261.x

42. Khalil M, Hamadah O, Maher Saifo, et al. Effect of photobiomodulation on salivary cytokines in head and neck cancer patients with oral mucositis: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(10):2822. doi:10.3390/jcm13102822