Health Care Costs and Clinical Outcomes of Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections: An Evaluation of Skin-Sparing Surgery

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Necrotizing soft tissue infection (NSTI) is a debilitating disease process that is characterized by rapid clinical progression and extensive tissue destruction, necessitating early surgical excision. Long-term care and outcomes of the resulting complex morbid wounds remain daunting. Objective. To review the skin-sparing surgery (SSS) approach to NSTIs and patient outcomes, including mortality rate, length of stay (LOS), and health care costs (HCC). Methods. The electronic medical records of patients treated at an adult regional burn and wound center between 2011 and 2021 and who underwent a SSS approach to wound closure were reviewed. Patients were excluded if surgical reports did not characterize widespread fulminant tissue destruction at multiple levels and use of a SSS approach. LOS, mortality rate, readmission rates, and HCC were also evaluated. Results. Seventy-one patients were included in the study. The mean number of SSS per patient during initial hospitalization was 3.56, and the mean number including revisions of all anatomic locations was 7.34. The initial hospital LOS averaged 23 days, and the initial encounter mortality rate was 1.4% (n = 1). The readmission rate within 30 days and within 90 days was 17% (n = 12) and 18% (n = 13), respectively. Further, 39.4% of patients were partially managed as outpatients during wound closure. The mean HCC over the treatment course, including indirect costs and direct costs, was $64 645.18 and $44 543.61, respectively. Conclusion. The results of this study show that the SSS approach to NSTI correlates with low mortality rates, decreased LOS, and low HCC. These findings can inform future studies involving the SSS approach as well as increase awareness of this alternative technique to surgeons caring for patients with NSTI.

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; EMR, electronic medical record; HCC, health care costs; LOS, length of stay; NSTI, necrotizing soft tissue infection; SSS, skin-sparing surgery.

NSTIs comprise rare but aggressive and life-threatening disease processes marked by rapid clinical progression and extensive tissue destruction that is generally belied by minimal cutaneous involvement. Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes (a major risk factor for the development of NSTIs) in the United States, the incidence of NSTIs has been steadily increasing.1-3 A previous study analyzing multiple national datasets estimated that the incidence of NSTI increased from 22 300 cases annually in 2012 to

33 600 in 2018.4 The estimated annual incidence was between approximately 8 and 10 per 100 000 people.4

Treatment of NSTI depends heavily on early recognition and expedient initiation of antibiotic therapy, traditionally accompanied by wide radical excision.5 Patients usually require repeat debridement procedures for control of the infectious process, which spreads rapidly along tissue planes.6-8 These multiple debridements often result in large, complex, open wounds that require extensive wound care and multiple operations for closure, many of which require skin grafting. Additionally, NSTIs are associated with frequent wound complications, such as infection and dehiscence, requiring readmission.2,9 Prior studies investigating the readmission rate within 90 days of initial hospitalization reported rates ranging from 24% to 30.3%4,9; in 1 study the most common complications associated with readmission were infection (65%), acute kidney injury (22%), and shock (10%).4

Not only does wound care associated with these complex and morbid wounds cause a strain on the health care system both in terms of resources and labor, but the cost of readmissions and repeated treatment of this infectious process contribute significantly to HCC. A 2021 study by Toraih et al9 examining more than 80 000 patients in the United States diagnosed with NSTI found that over 30% of these patients required readmission within 90 days. The median cost of readmission was $10 543, and readmission contributed an additional 174 640 hospital days for these patients. This resulted in an estimated financial burden of $1.4 billion. May et al4 reported a median cost of readmissions related to NSTI of $13 590, with median LOS of 7 hospital days for each readmission.

In 2010, researchers from the Department of Surgery, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, first described large skin preservation surgery in a patient with necrotizing fasciitis in which 41% of wound closure was achieved with spared skin and soft tissue.10

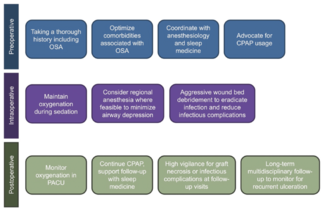

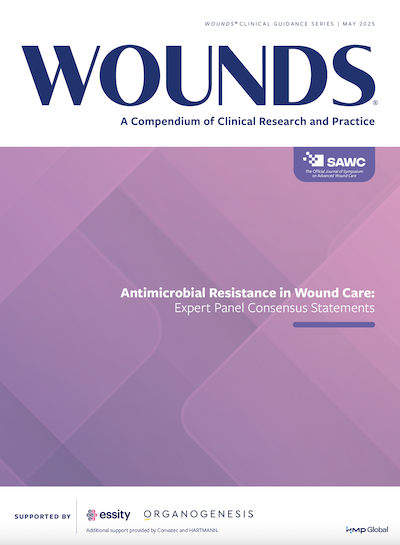

The skin-sparing approach to NSTI debridement was also described in a 2016 study by Tom et al,11 which focused on initial debridement with removal of necrotic and infected tissue while preserving overlying skin and associated vascular arcade for the purposes of wound closure. In that study, delayed primary closure was achieved in all but 1 of the 11 documented cases treated with skin-sparing NSTI debridement. Wong et al12 were the first to classify the infected skin into 3 different zones of skin and soft tissue involvement: zone 1 is the sentinel area of infection with full-thickness necrosis, zone 2 radiates centrifugally around zone 1 as an area of cellulitis, and zone 3 is normal skin and soft tissue (Figure 1A).

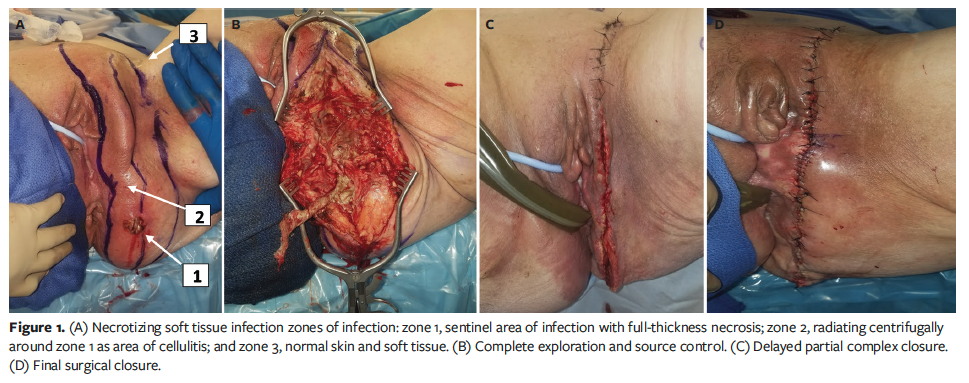

This technique has previously been described in detail in patients with Fournier gangrene, utilizing a concurrent triad of surgical debridement, complex closures, and negative pressure wound therapy. Use of this reproducible technique repeatedly resulted in a decreased need for skin grafting and diverting colostomy as well as the ability to partially manage patients on an outpatient basis during wound closure.13-15 The SSS technique involves incising over the area of prominent necrosis, creating a full-thickness exploratory incision on either side of the spared skin and soft tissue flaps to evaluate the extent of disease, creating counter-incisions as needed, and excising all necrotic tissue to include grossly necrotic skin (Figure 1B and Figure 2A). This allows for reevaluation of tissue left in situ to determine if skin and soft tissue are viable and can be used for wound closure.13,15

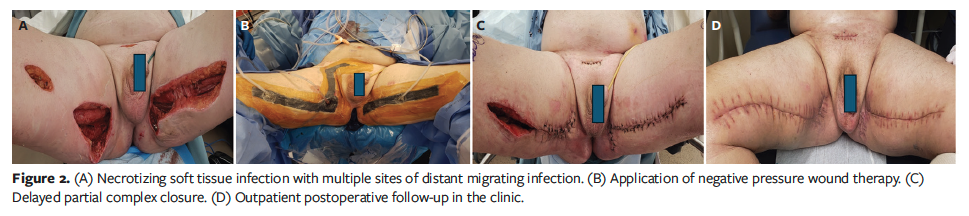

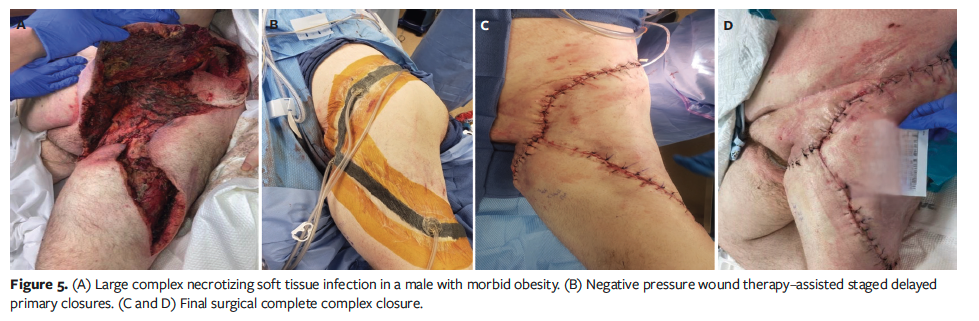

Because the financial burden and incidence of NSTIs among the general population (especially among those with diabetes) is increasing, decreasing hospital resource utilization is a constant goal to allow for better treatment of a larger number of patients. Hospitals and physician providers have sought an intervention that would decrease the LOS and readmission rate by decreasing wound morbidity while still providing adequate and expedient treatment of NSTIs. The skin and soft tissue–sparing surgical approach to NSTIs is a possible avenue. NSTIs tend to have extensive necrosis and centrifugal spread of infection with minimal cutaneous involvement (Figure 2). Historically, the traditional wide radical excision encompassed both the dead tissue as well as the surrounding overlying epidermal and dermal cellulitis. In contrast, the SSS approach preserves the overlying skin in zones 2 and 3 while resecting only necrotic subcutaneous soft tissue, dermis, and fascia (Figure 3A-D).12-14 As demonstrated in Figures 1-5, the overlying skin flaps allow for delayed primary wound closure, thus decreasing the need for skin grafting, which is associated with extensive scar contractures, defect deformities, and reduced functionality.6,12 Notably, Tom et al12 reported a 20% rate of skin grafting following debridement for NSTIs after using the SSS technique compared with a 90% rate of skin grafting using the traditional approach.

Limited data on SSS techniques and outcomes currently exist in the literature. Further, there is a paucity of data regarding costs associated with the SSS approach. The present study sought to evaluate the effect of the skin and soft tissue–sparing surgical approach in the management of NSTI in terms of clinical outcomes and HCC.

Methods

Objectives

The primary objective of the present study was to evaluate hospital LOS, mortality rate, and readmission rates of patients treated with the SSS approach to NSTI. Secondary outcomes evaluated included fixed and variable HCC incurred during the treatment process, in addition to indirect cost of hospitalization. Demographic and surgical outcome data were evaluated as well. This single-center retrospective study was reviewed and approved by the Wright State University Institutional Review Board.

Patient selection

The EMRs of patients who were treated at the authors’ adult regional burn and wound center between 2011 and 2021 and who underwent a SSS approach to wound closure were reviewed. Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, codes as well as CPT codes for NSTI, which included necrotizing fasciitis, Fournier gangrene, diabetic foot wound, abscess, spinal wound, and abdominal wound. Next, CPT codes were used to capture the patients who underwent the SSS approach. The surgical reports for these patients were then reviewed.

Additionally, an archival review of patients known to have undergone the SSS approach to NSTI treatment were

included after also reviewing their surgical reports for consistency. Patients without a SSS approach to surgical intervention or evidence of NSTI on review of the surgical report were excluded. The incision was determined to be skin sparing if there was noted undermining and tissue flap creation.

Data collection

Demographic data—including comorbidities such as tobacco dependence, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (eg, coronary artery disease)—were analyzed for eligible patients. Additional data points were obtained, including initial hospital LOS, mortality rate, wound measurements, number of surgeries during the treatment course, additional admissions, and total LOS throughout the entire treatment course. Charts were reviewed for accuracy. Sex and race were self-reported. Race and ethnicity help to ensure research is generalized and inclusive to any potential disparities.

HCC data were provided after an EMR database search for relevant hospitalizations and outpatient procedures. The HCC mined included variable and fixed cost, which includes components such as patient care labor, supplies, benefits, equipment depreciation, and physician cost. Indirect costs were also calculated and include all non–patient care departments involved in hospital management, such as maintenance, utilities, and accounting. The HCC over the entirety of the treatment process, including outpatient surgical events, were combined for each patient. All data were analyzed descriptively.

Results

Patient demographics

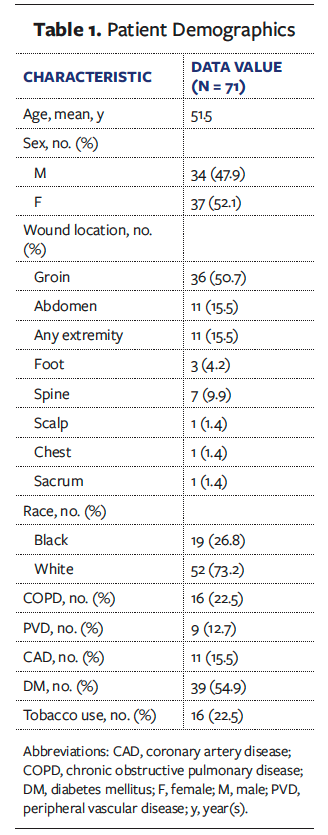

Seventy-one patients were identified as being eligible for the study based on their diagnosis of NSTI and surgical reports reflecting use of the skin-sparing surgical approach. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. Among the 71 patients included were 37 female patients (52.1%) and 34 male patients (47.9%). The average age was 51.5 years. In terms of race, 73.2% were White and 26.8% were Black. Wound location varied considerably, but the majority of patients (n = 36 [50.7%]) had groin/perineal wounds consistent with Fournier gangrene. Other wound locations included the chest, abdomen, extremities, spine, scalp, and sacrum. Notable comorbidities in this patient population included diabetes, present in 54.9% of the patients, tobacco use (22.5%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (22.5%). The comorbidities peripheral vascular disease and coronary artery disease were also included in subgroup analysis.

Clinical outcomes

The average wound surface area after initial debridement was 619.7 cm² (range, 51 cm²-4400 cm²). The average number of surgeries at initial hospitalization was 3.56 surgeries per patient treated with the SSS approach. The average number of surgeries per patient, including revisions of all anatomical locations, was 7.34. Twenty-eight of the 71 patients (39.4%) underwent 1 or more outpatient surgeries for wound closure/revision after the index admission. All surviving patients treated with the SSS approach achieved delayed primary closure.

The initial hospital LOS for patients whounderwent the SSS approach averaged 22.7 days (median, 16 days). The mortality rate for the initial hospitalization was 1.4% (n = 1). The overall hospital LOS involving all surgical debridement, reconstructions, and revisions during the evaluated years was 24.01 days (median, 9 days). The acute readmission rate (<30 days) for wound infections and dehiscence was 17% (n = 12). The total readmission rate at 90 days following presentation and first debridement was 18% (n = 13).

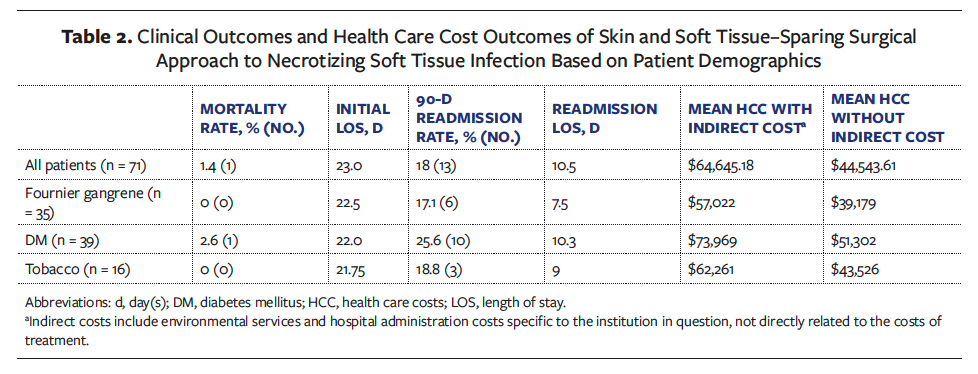

Table 2 summarizes clinical outcomes and HCC among all evaluable patients. Further subgroup analysis of patients with Fournier gangrene showed decreased mortality, initial hospital LOS, and 90-day readmission rate in this population compared with all patients. In contrast, patients with diabetes had increased mortality, 90-day readmission rate, and overall HCC compared with all patients. Patients with a history of tobacco use had a lower rate of readmissions compared with those patients with diabetes.

HCC utilization

The mean HCC during the entirety of patient treatment, including indirect costs to the patient, was $64 645.18 (median, $22 283.25). The mean HCC without indirect costs to the patient was $44 543.61 (median, $15 742.56). As shown in Table 2, patients with diabetes incurred higher HCC compared with those with a history of tobacco use.

Discussion

Qualitative research indicates that SSS in the management of NSTIs continues to show promising outcomes. The present study is the first to analyze clinical and hospital care cost data of NSTIs managed using a skin-sparing surgical approach. The qualitative analysis of SSS in NSTIs has been previously described and illustrated by the authors of the present article.13,15 In the present study, the analysis was extended to review HCC outcomes in the management of NSTIs using skin and soft tissue–sparing surgery. The overall goal was to highlight patient outcomes regarding hospital LOS and overall cost of treatment, as well as the benefit of using delayed primary closure rather than skin grafting for these complex wounds. To the authors’ knowledge, this is also the largest study evaluating hospital care cost and clinical outcomes using skin and soft tissue sparing–surgery for NSTIs.

The present study demonstrated an overall low mortality rate of 1.4% within the population of 71 patients. Mortality rates as high as 40% for patients with NSTI have been reported16,17; however, historically, mortality rates for NSTI have ranged from 11% to 22%.18,19 The average LOS in the present study was 22.7 days for the initial hospitalization, with a median of 16 days. While other centers have reported a significantly higher LOS (up to 69 days) for these patients,1 the results in the present study corroborate with the more frequently reported LOS range of 3 days to 40 days.20,21 In the present study the readmission rate for acute wound complications was found to be 18% within 90 days, compared with a range of 24% to 29% in the literature.1,4,9,22 In the present study, the average LOS for each hospitalization per NSTI patient was 15.32 days, with a total LOS for all hospitalizations per NSTI patient (including readmissions and outpatient revisions) of 24.01 days; 39.4% of this patient population was partially managed on an outpatient basis. The mean hospital cost per patient of the skin-sparing surgical approach was $44 543.61, which includes costs directly related to patient care only; this cost is less than the $64 517 per NSTI patient cost of the traditional approach reported in a previous study.21 These results show that the skin and soft tissue–sparing surgical approach to NSTI is associated with low mortality rates, hospital LOS, and overall estimated HCC.

Limitations

The limitations of the present study, as with many studies involving NSTIs, include low sample size. This is a small sample group because it involved review of records at a single institution at which a single surgeon used this specific technique over the course of 10 years. Given these limitations, this study lacks direct comparative capacity and statistical analysis for significance. In addition, the differing definitions of direct and indirect costs across institutions makes any direct cost comparison with values in the literature difficult. Inflation over the 10-year span also affects health care institutions differently across the United States, which makes comparisons outside the authors’ institution difficult. The study focused heavily on initial debridement techniques and subsequent reconstruction; thus, patients who underwent repeated surgeries for their treatment were selected in searching for CPT codes consistent with staged delayed primary closures involving the SSS approach. Patients who died after a single procedure were not included in the study, which may have contributed to the lower mortality rate compared with other studies.

Conclusion

The use of SSS in the management of NSTIs stands in contrast to the traditional approach of progressive wide radical excision. This reproducible SSS technique has proven to be a viable alternative that is associated with reduced LOS, mortality, split-thickness skin grafting, and overall low hospital resource utilization. This study partially addresses the paucity of data in the current literature regarding the promising benefits of SSS in the management of NSTIs.

Authors of this study are planning future studies that focus on cost comparisons between the traditional wide radical excision approach to NSTI vs the skin-sparing surgical approach in order to allow for patient matching and standardization of cost data collection, which will enable statistical analysis and determination of significance. Additionally, a health care-associated quality of life survey is planned to follow up with the patients treated with the SSS approach to assess their satisfaction with their wound management, cosmesis, and functional limitations compared with patients treated with wide radical excision.23 Currently, there is a paucity of data in the literature regarding quality of life following NSTI treatment of any sort, so further study in this area may prove useful to help delineate the most appropriate and beneficial surgical approach. These qualitative outcomes may further inform future quantitative studies in the evaluation of HCC and quality of life using the SSS approach as well as foster increased awareness of this alternative technique for treating patients with NSTI.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Travis L. Perry, MD; Jordan Silverman, MD; Courtney Johnson, DO; Benjamin Kleeman, BS; and Priti Parikh, PhD

Affiliations: Department of Surgery, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, USA

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Patrick Siler for data mining. The authors would also like to acknowledge Phillip Heyse, MD; Lindsay Kranker, MD; Eileen Curry, MD; and Michael Johnson, MD, for coauthorship of an earlier case series on necrotizing soft tissue infection.

Correspondence: Travis L. Perry, MD; Wellstar Cobb Hospital Attn: Burn Clinic, 3950 Austell Road, Austell, GA 30106; travis.perry@burncenters.com

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest. This study received no funding. The original data contained in this article were accepted for an oral presentation at the 18th Annual Academic Surgical Congress, which was held February 7-9, 2023, in Houston, TX.

Ethical Approval: This single-center retrospective study was reviewed and approved by the Wright State University Institutional Review Board.

Manuscript Accepted: March 20, 2025

References

1. Kobayashi L, Konstantinidis A, Shackelford S, et al. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: delayed surgical treatment is associated with increased number of surgical debridements and morbidity. J Trauma. 2011;71(5):1400–1405. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31820db8fd

2. Mills MK, Faraklas I, Davis C, Stoddard GJ, Saffle J. Outcomes from treatment of necrotizing soft-tissue infections: results from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Am J Surg. 2010;200(6):790–797. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.008

3. Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, Schwab CW. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(2):279–288. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.032

4. May AK, Talisa VB, Wilfret DA, et al. Estimating the impact of necrotizing soft tissue infections in the United States: incidence and re-admissions. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2021;22(5):509–515. doi:10.1089/sur.2020.099

5. Endorf FW, Cancio LC, Klein MB. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections: clinical guidelines. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(5):769–775. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181b48321

6. Hua C, Bosc R, Sbidian E, et al. Interventions for necrotizing soft tissue infections in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD011680. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011680.pub2

7. Gelbard RB, Ferrada P, Yeh DD, et al. Optimal timing of initial debridement for necrotizing soft tissue infection: A Practice Management Guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(1):208–214. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001857

8. Norton KS, Johnson LW, Perry T, Perry KH, Sehon JK, Zibari GB. Management of Fournier’s gangrene: an eleven year retrospective analysis of early recognition, diagnosis, and treatment. Am Surg. 2002;68(8):709–713.

9. Toraih E, Hussein M, Tatum D, et al. The burden of readmission after discharge from necrotizing soft tissue infection. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91(1):154–163. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003169

10. Perry TL, Heyse RP, Little A, Johnson M. Large flap preservation in a patient with extensive necrotizing fasciitis: is vertical transmission of infection directly proportional to centrifugal spread of disease?. Wounds. 2010;22(6):146–150.

11. Tom LK, Wright TJ, Horn DL, Bulger EM, Pham TN, Keys KA. A skin-sparing approach to the treatment of necrotizing soft-tissue infections: thinking reconstruction at initial debridement. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(5):e47-60. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.01.008

12. Wong CH, Yam AKT, Tan ABH, Song C. Approach to debridement in necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 2008;196(3):e19–e24. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.076

13. Tom LK, Maine RG, Wang CS, Parent BA, Bulger EM, Keys KA. Comparison of traditional and skin-sparing approaches for surgical treatment of necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2020;21(4):363–369. doi:10.1089/sur.2019.263

14. Perry TL, Kranker LM, Mobley EE, Curry EE, Johnson RM. Outcomes in Fournier’s gangrene using skin and soft tissue sparing flap preservation surgery for wound closure: an alternative approach to wide radical debridement. Wounds. 2018;30(10):290–299.

15. Kranker LM, Curry EE, Perry TL. Response to Tom et al., Comparison of traditional and skin-sparing approaches for surgical treatment of necrotizing soft-tissue infections (DOI: 10.1089/sur.2019.263). Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2020;21(5):474–475. doi:10.1089/sur.2020.037

16. Bruun T, Rath E, Madsen MB, et al. Risk factors and predictors of mortality in streptococcal necrotizing soft-tissue infections: a multicenter prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(2):293–300. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa027

17. Kumar T, Kaushik R, Singh S, Sharm R, Attri A. Determinants of mortality in necrotizing soft tissue infections. Hell Cheirourgike. 2020;92(5):159–164. doi:10.1007/s13126-020-0568-1

18. Pasternack MSM. Cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, and subcutaneous tissue infections. In: Mandell G, Bennett J, Dolin R (eds). Mendell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practices of Infectious Disease. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2015:1195–1216.

19. Nawijn F, Smeeing DPJ, Houwert RM, Leenen LPH, Hietbrink F. Time is of the essence when treating necrotizing soft tissue infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:4. doi:10.1186/s13017-019-0286-6

20. Tahmaz L, Erdemir F, Kibar Y, Cosar A, Yalcýn O. Fournier’s gangrene: report of thirty-three cases and a review of the literature. Int J Urol. 2006;13(7):960–967. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01448.x

21. Widjaja AB, Tran A, Cleland H, Leung M, Millar I. The hospital costs of treating necrotizing fasciitis. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(12):1059–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03622.x

22. Urbina T, Canoui-Poitrine F, Hua C, et al. Long-term quality of life in necrotizing soft-tissue infection survivors: a monocentric prospective cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):102. doi:10.1186/s13613-021-00891-9

23. Czymek R, Kujath P, Bruch HP, et al. Treatment, outcome and quality of life after Fournier’s gangrene: a multicentre study. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(12):1529–1536. doi:10.1111/codi.12396