The Effect of COVID-19 on Diabetic Foot Ulcer Surgery at a Safety Net Hospital

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Management of diabetic foot ulcers requires detailed and continuous work. Social distancing and lockdown restrictions instituted during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 were essential to saving lives and preventing hospital overflow, but they caused many difficulties for patients and health care providers. Objective. To show the changes in wound care surgery affected by COVID-19 at a safety net hospital. Methods. All ulcer-related surgeries performed at a single institution from March 2018 through February 2023—that is, 2 years before, the year of, and 2 years after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic—were reviewed. Because the imposed outpatient and elective surgery restrictions started in March 2020, the period from March through February was used for the review. Wound-related surgeries included wound debridement, incision and drainage, exostectomy, digit amputations, midfoot amputations, and major amputations. Results. During the entire period, 1858 ulcer-related surgeries were performed at the authors’ institution. A total of 723 surgeries were performed in the 2 years before COVID (pre), with 368 performed in the initial year of COVID (Covid) and 767 in the 2 years after the first year of the pandemic (post). Conclusion. COVID-19 significantly impacted various aspects of ulcer management at the clinic. The authors’ wound clinic remained open on a limited basis, and the number of patients seen was markedly lower. After the restrictions were lifted, wound care visits remained significantly lower than the pre-pandemic level; the fear of COVID-19 had a lasting impact on the number of visits. The number of exostectomy and digit amputations has increased since the first year of the pandemic. Midfoot amputation and major amputation did not change much after the initial year of the pandemic, which may be due to death from COVID-19. The fear and death associated with COVID-19 affected wound care and continue to affect wound care and limb salvage, but determining the actual number affected is challenging.

Each year, approximately 1.6 million people in the United States and 18.6 million people worldwide are affected by diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs).1 Neurological, vascular, and biomechanical factors contribute to DFU. Approximately 50% to 60% of ulcers become infected, and about 20% of moderate to severe infections lead to lower extremity amputations.1

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Covid-19 virus a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 31, 2020.2 The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Alex Azar, declared the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak a public health emergency on the same day.3 On February 11, 2020, the WHO announced the name of the disease that caused the 2019 Novel Coronavirus outbreak: COVID-19, an abbreviation of Coronavirus Disease 2019.4 On March 11, 2020, the WHO International Health Regulations Emergency Committee declared the coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of international concern.5 COVID-19 was then proclaimed a pandemic. Local governments and the US Department of Public Health ordered a stop to nonessential surgery starting March 18, 2020, based on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

recommendation to discontinue all non-emergent medical services.6 States began to implement shutdowns and advised people to stay home to prevent the spread of COVID-19.7

A review by Pride et al showed substantial decreases in surgical volume across specialties, which were observed in the following months.8 Winter Beatty et al related an estimated cancellation or delay of 28 million nonurgent surgeries globally.9 Wound care was severely affected due to the decreased ability for follow-up and the generalized fear of COVID-19. Pride et al noted that the disruption in regular access to wound care caused by the pandemic and patients’ perception of safety caused significant problems in managing diabetes and related foot complications.8 Outpatient clinics were consolidated, staff were furloughed, patient appointments were rescheduled or canceled, and telemedicine was used to conduct visits. The wound clinics at Boston Medical Center remained open on a limited basis; many patients had to go to the emergency department for care.

Several operating rooms and postoperative care units were converted into patient rooms. There was an increase in patients seen in the emergency department for wound care after their wounds had become infected, often severely infected. As a result, more urgent surgeries were required. Vascular and podiatric services at Boston Medical Center used the most operating time during the pandemic. The authors’ hospital-based clinic sees an average of 25 000 patients of all pathologies, both new and follow-up, yearly, or approximately 2100 per month (2 100 × 12 = 25 200), 480 per week (480 × 52 = 24 960), or 100 per day (100 × 5 = 500). Not counting inpatients, wound care accounts for 25% of the patient volume, with 25 patients treated daily. Vascular and podiatry services see 95% of wound patients, excluding postoperative visits during the restriction period from March 2020 to October 2020. Podiatric service saw approximately 10 wound patients daily at a location different from our usual wound clinic. After the restriction was lifted at the beginning of November 2020, it took more than a year for the clinic to return to normal.

Many reviews on the effect and management of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes have been published.10,11,12 Shin et al reported some cases affected by COVID-19.13 The present study's authors observed similar cases during the COVID-19 pandemic, many requiring foot and leg amputations. There are many guidelines for managing DFU, diabetic foot infection (DFI), and critical limb ischemia.14,15,16 Although healthcare workers continued to follow the guidelines, the pandemic made patient management difficult.

The present study examines the impact of COVID-19 outpatient service and elective surgery restrictions on the number of wound surgeries performed during and after the initial year of the pandemic at a safety-net hospital. The number of ulcer-related surgeries performed before, during, and after the first year of the pandemic was analyzed to examine the potential social and medical impacts of COVID-19 on ulcer care and amputations. The institutional review board of the authors’ institution approved this review with an exemption.

Methods

The number of ulcer-related surgeries performed in a safety net institution from March 2018 through February 2023 was reviewed. All patients were diagnosed with diabetes and peripheral artery disease. These data were compared with other scheduled surgeries in the same period. For this study, the annual reports run from March of 1 year through February of the following year. This coincides with the restriction of nonessential surgery in March 2020. The COVID year periods are as follows: pre-2018-19 (March 1, 2018-February 28, 2019); pre-2019-20 (March 1, 2019-February 29, 2020); COVID-2020-21 (March 1, 2020-February 28, 2021); post-2021-22 (March 1, 2021-February 28, 2022); and post-2022-23 (March 1, 2022-February 28, 2023).

The authors of the present manuscript reviewed all wound-related surgeries performed in the periods noted above. These surgeries were categorized as wound bed debridement (WDB), incision and drainage (IND), exostectomy (EXO), digit amputation (DAM), midfoot amputation (MFA), and major amputation (MJA). WDB consisted of removing necrotic or devitalized tissue. Only the debridement done in the operating room was captured for this study. IND involved the removal of the deep necrotic tissue, dead and senescent cells, and osteomyelitic bones. EXO involved the removal of the bony prominence causing ulceration, including distal phalangectomy, metatarsal head resection, Charcot EXO, and calcanectomy. DAM involved the removal of the phalanx and part of the metatarsal. MFA included transmetatarsal, Lisfranc, and Chopart amputations. MJA included below-knee and above-knee amputations. Revision amputations were not counted. Traumatic amputations, Charcot reconstruction, and all nondiabetic soft tissue procedures were excluded. At this safety net hospital, race, ethnicity, and other disparities affected the care of patients; the pandemic deepened the gap. The authors discuss herein how COVID-19 contributed to this gap.

Results

Nonamputations

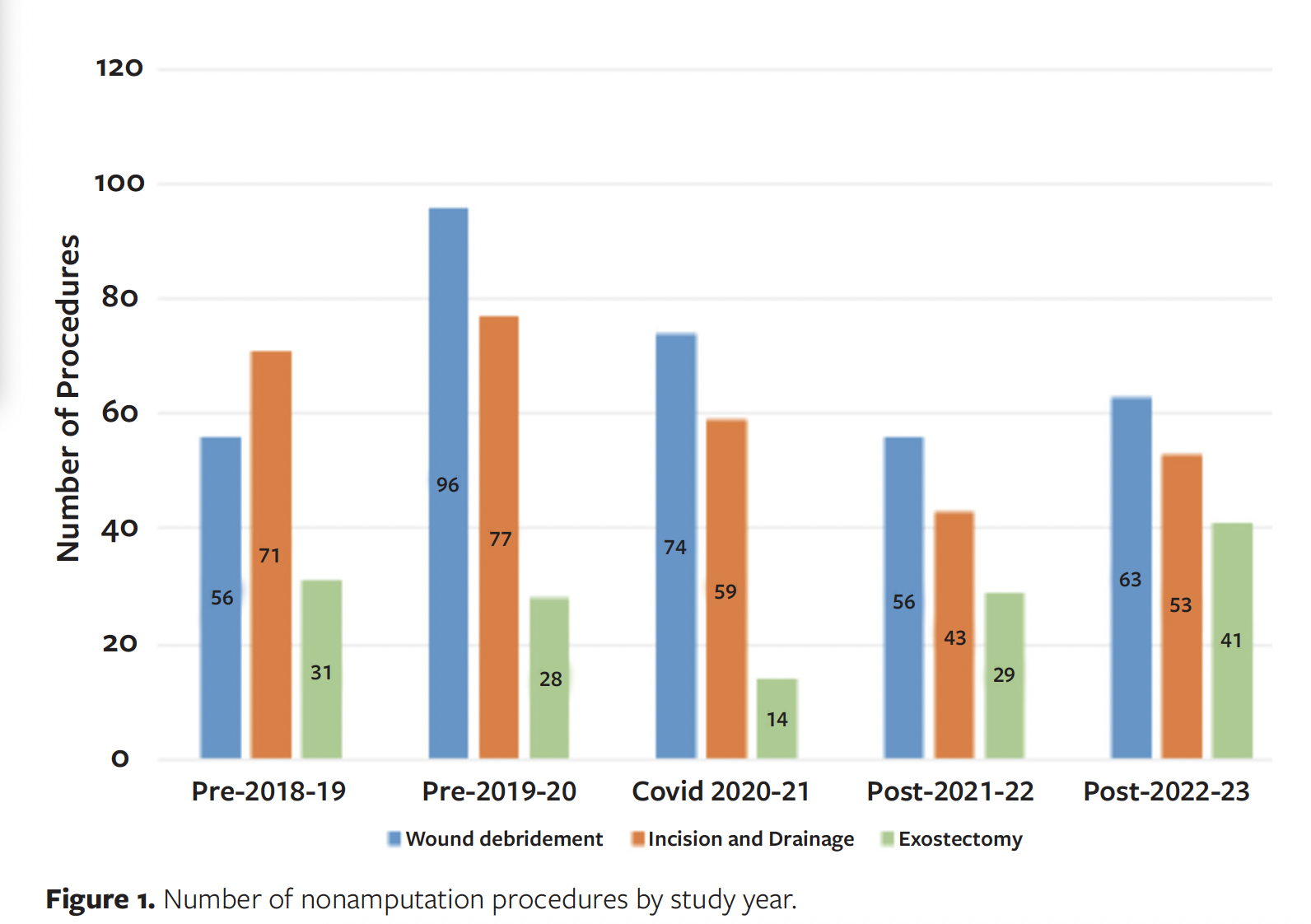

WDBs and INDs were trending up in pre-2018-19 and pre-2019-20, dropped in COVID-2020-21 and post-2021-22, but increased in post-2022-23 (Figure 1). EXOs were level during the pre-2018-19 and pre-2019-20, dropped in COVID-2020-21, and sharply increased in post-2021-22 and post-2022-23. Levels dropped markedly from pre-2019-20 to COVID-2020-21 for all 3 treatments, which may indicate difficulty accessing care. Patients could not go to the clinic and could not get an operating time.

Amputations

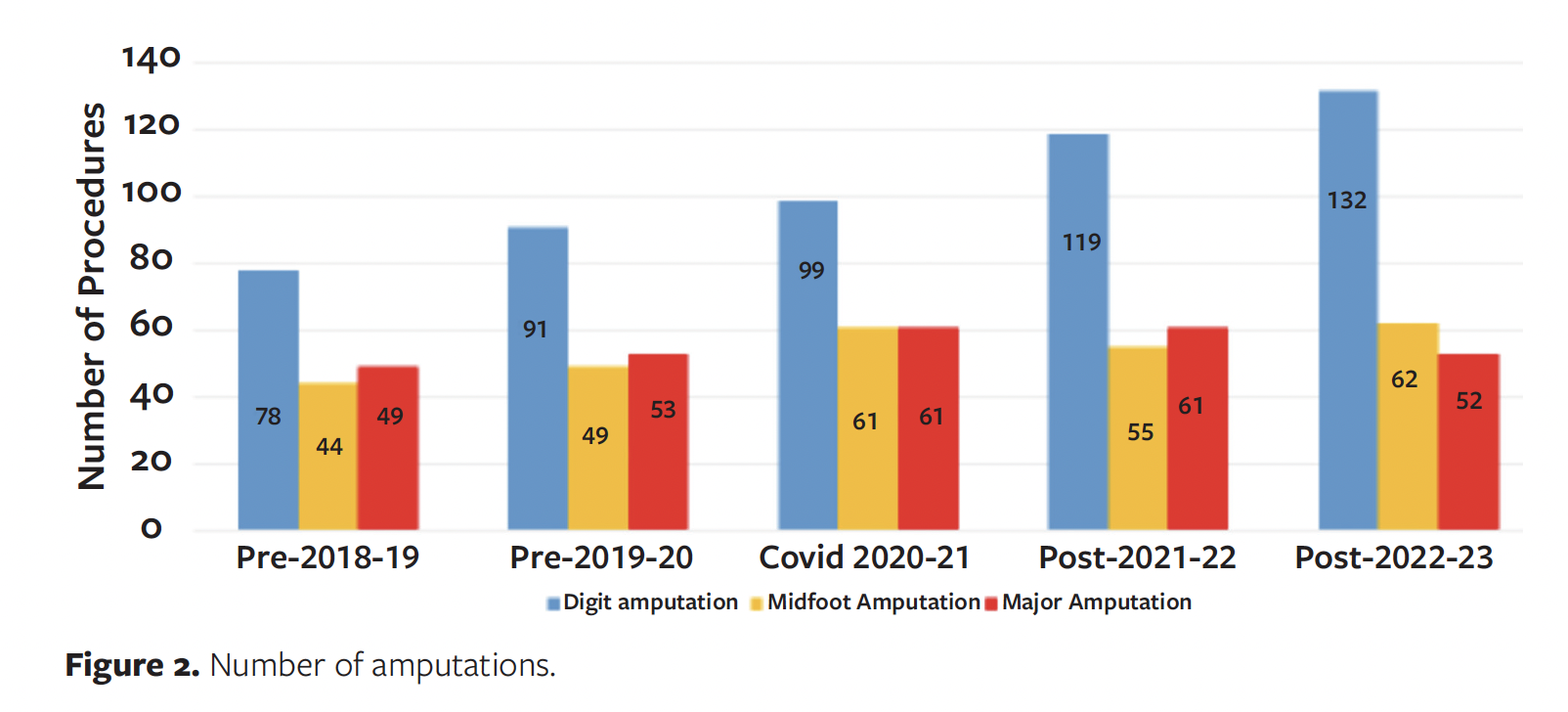

DAM was shown to be the most common type of amputation in many studies and may precede limb loss.17,18 Similar data were observed at the institution where the authors of the present study are based. The number of DAMs would have been higher had partial amputations been counted. The data in the present review showed that DAMs continued to increase each period studied. From pre-2018-19 to pre-2019-20, there was a 17% increase in DAMs, with an increase of 9% from pre-2019-20 to COVID-2020-21, 20% from COVID-2020-21 to post-2021-22, and 11% from post-2021-22 to post-2022-23 (Figure 2). Overall, there was a 69% increase in DAMs from pre-2018- 19 to post-2022- 23. COVID-19 may have influenced this increase.

MFAs have been used as limb salvage procedures because patients can ambulate better following MFA than after more proximal amputation. MFAs increased by 11% from pre-2018-19 to pre-2019-20, increased by 24% from pre-2019-20 to COVID-2020-21, dropped by 10% from COVID-2020-21 to post-2021-22, and rebounded by 13% by the following year (post-2022-23) to the level of COVID-2020-21 (Figure 2).

MJAs increased by 8% from pre-2018-19 to pre-2019-20 and increased by 15% from pre-2019-20 to COVID-2020-21; the number stayed the same the following year (post-2021-22) and then dropped 13% from post-2021-22 to post-2022-23 (Figure 2).

All 3 types of amputation increased from pre-2019-20 to COVID-2020-21, showing the effect of COVID-19. Some MFAs and MJAs may not have been captured due to either access to care or mortality during the pandemic.

All surgical procedures

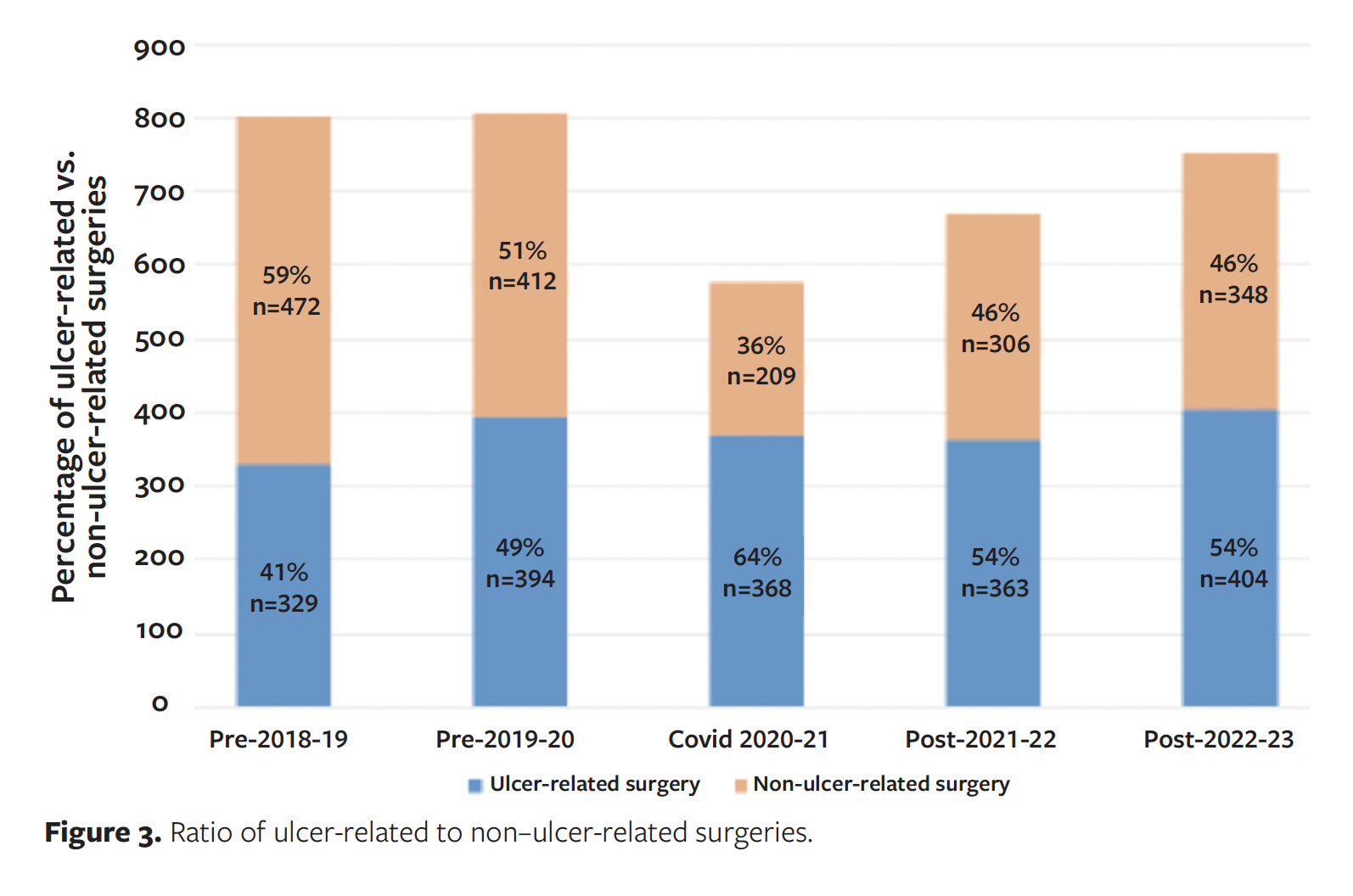

The percentage of ulcer-related procedures versus non–ulcer-related surgeries, respectively, for each period was 41% vs 59% in the pre-2018-19 period, 49% vs 51% in the pre-2019-20 period, 64% vs 36% in the COVID-2020-21 period, 54% vs 46% in the post-2021-22 period, and 54% vs 46% in the post-2022-23 period (Figure 3). The data showed that the number of elective surgeries in the department was high before the lockdown. That number dropped significantly because of the restriction, then bounced back, but as of this writing it had not reached the same level as pre-2019-20. Many studies showed an increase in amputations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rogers et al cited reports of amputation increased up to 3 times compared to pre-pandemic.19 Pride et al cited many studies showing an increase in amputation rates.8 Casciato et al showed that the number of foot-related surgeries increased from pre-pandemic to pandemic, but not significantly, and the number of major amputations increased significantly.20 Ergişi et al concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic did not indirectly influence the incidence or severity of lower extremity amputations resulting from diabetes-related complications, despite potential disruptions to routine medical care.21 The present study, however, showed that although DAMs continued to increase from pre-2018-19 to post-2022-23, MFAs and MJAs did not exhibit significant variation over these 5 years (Figure 2).

Mortality

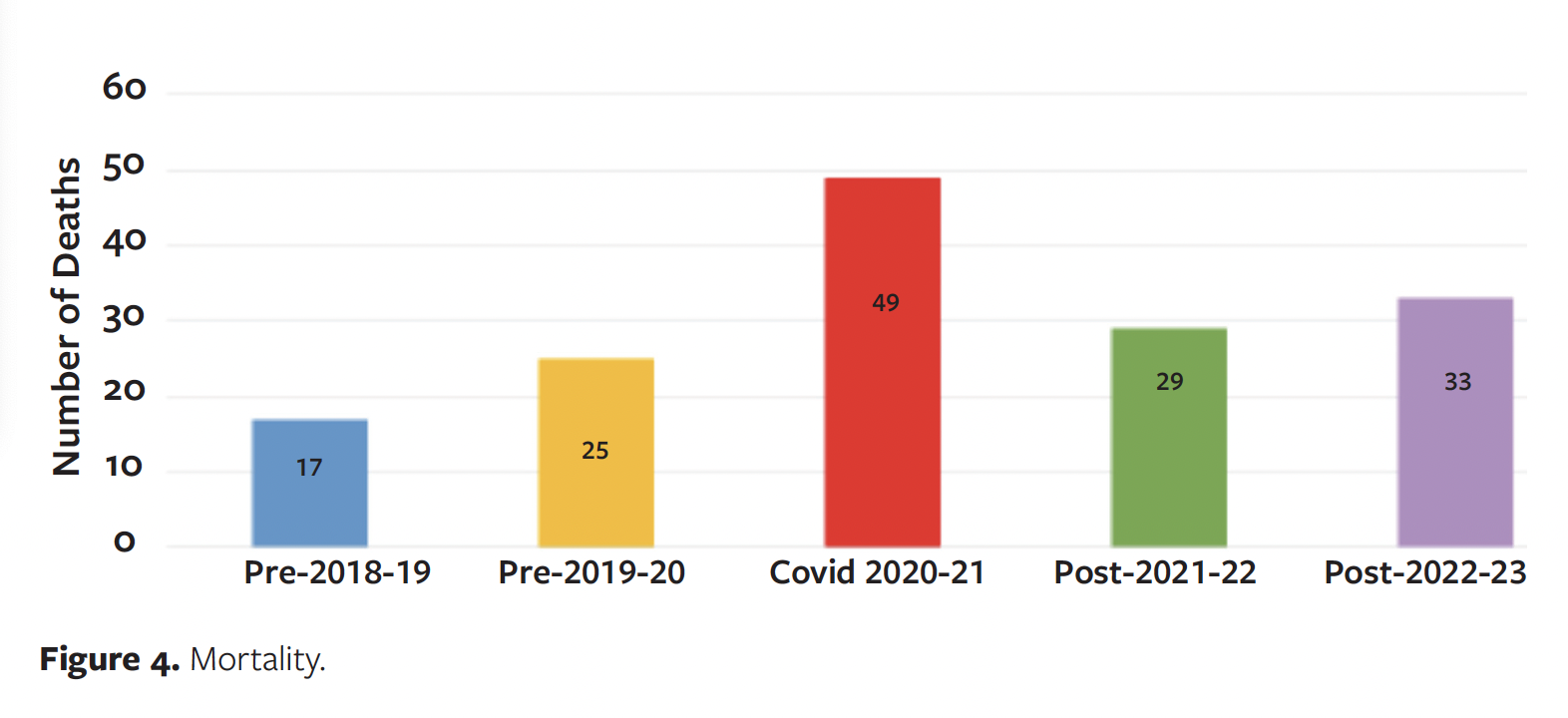

COVID-19 caused many deaths, with even more COVID-19-related morbidity. At the authors’ institution, there was a 47% increase in mortality from pre-2018-19 to pre-2019-20, a 96% increase from pre-2019- 20 to COVID-2020-21, a 41% decrease from COVID-2020-21 to post-2021-22, and a 13.8% increase from post-2021-22 to post-2022-23. Of the 49 deaths in the COVID-2020-21 time frame, 15.2% (8) were in the nonamputation group, 41.3% (20) had DAMS and MFAs, and 43.5% (21) had MJAs. This showed the devastating effect of COVID-19 on severe ulcer conditions and the ability to manage the ulcers (Figure 4).

Overall results

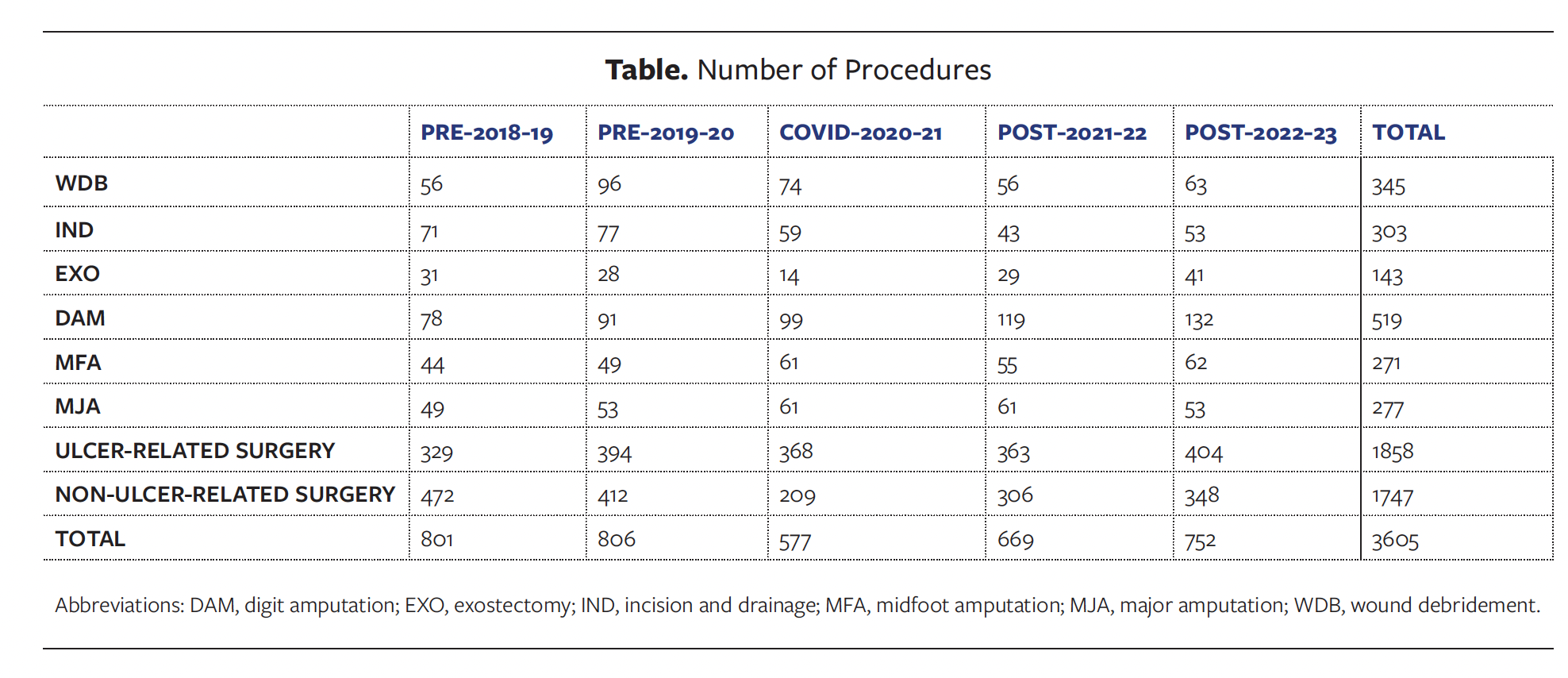

Overall, from March 1, 2018, to February 28, 2023, there were 1858 ulcer-related procedures, not counting any revision procedures. There were 345 WDBs, 303 INDs, 143 EXOs, 519 DAMs, 271 MFAs, and 277 MJAs (Table). There were 1747 non–ulcer-related procedures in the same period: 472 in pre-2018-19, 412 in pre-2019-20, 209 in COVID-2020-21, 306 in post-2021-22, and 348 in post-2022-23. Complete details on ulcer-related and non–ulcer-related surgeries performed in the study period are shown in the Table.

Discussion

The pandemic affected all levels of wound care at the institution discussed in the present study. During the early period of restrictions in the pandemic, clinics were only open to patients requiring wound care. It was necessary to wear gowns, double masks, and double gloves when debriding wounds. Wound care visits decreased by more than 50%. Almost all patients seen during this restricted period needed debridement, but the present review does not include the data on debridement done in the clinic. When patients needed to go to the operating room for WDB, IND, EXO, or MFA, they had to be treated as having positive COVID-19 test results; all surgical team members wore double gowns, gloves, and masks, and the procedure had to be performed in a negative-ventilation room. The vascular surgery team handled all MJAs with similar operating restrictions. In the present study, WDB, IND, and EXO are categorized as nonamputation procedures, and DAM, MFA, and MJA are categorized as amputation procedures. Wound care begins with debridement, which can usually be performed in the clinic. Some WDB and IND for serious wounds traditionally performed in the operating room had to be done in a clinic or emergency department during the restricted period because of the need for operating room availability; thus, those instances were not captured in this review. Many operating rooms and postanesthesia care units were converted into patient rooms.

In this review, health disparities are evident among the patients included in this study. The 2020 United States Census showed that among the general population, 61.6% are White, 14.4% are Black, and 18.7% are Hispanic or Latino. However, of patients in the review pool in the present study, 28.1% identified as White, 41.3% as Black, and 19.7% as Hispanic. These statistics highlight that ethnic minority groups, who are already disproportionately affected by diabetes and its complications, were more vulnerable to diabetes complications during the initial year of the pandemic. For many patients who receive care at the authors’ institution, English is not the primary language they use for communication: 14.4% use Spanish, and 10.9% use other languages, including Albanian, Arabic, Bengali, Cambodian, Cantonese, French, French Creole, Italian, Krio, Polish, Portuguese, Portuguese Creole, Punjabi, Russian, Somalian, Swahili, Tamil, Ukrainian, Vietnamese, and sign language. Having to rely on limited telemedicine further contributed to language barriers, allowing for avenues for miscommunication and hindering effective diagnosis, treatment, and education. Managing DFU evaluation and treatment was also limited to telehealth, further delaying treatment and increasing the need for emergency procedures.

Insurance coverage and housing were other disparities evaluated in this study. Of the surveyed patients, 12% did not have health insurance, 21% had Medicare, and 33% had Medicaid or MassHealth. Concerning housing, 61% of patients lived in apartments (many subsidized), 5% in shelters, and 4% in rehabilitation or nursing homes.

Ethnic minority populations, particularly Black and Hispanic patients, had a higher incidence of lower extremity amputations compared with White patients. Among patients with DAM and MFA, 26% are White, 45% are Black, and 20% are Hispanic. Among patients with leg amputations, 34% are White, 44% are Black, and 10% are Hispanic.

Studies have shown that during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients faced several barriers to accessing medical clinics and hospitals, including a lack of public transportation and fear of infection.9,22 These concerns exacerbated complications with limited access to podiatry clinics and wound care centers. This disruption in care likely resulted in more associated lower limb amputations than is typical. These socioeconomic disparities were prevalent in the reviewed patient population even before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic amplified the existing struggles of marginalized groups in terms of comorbidities, employment, and housing. The present study helps to highlight the need for further support in institutions that serve patients with these various socioeconomic disparities, given these patients’ increased susceptibility to emergency procedures.

The increase in wound-related surgeries compared to non–ulcer-related surgeries in the present study highlights the importance of podiatric care, encompassing not only wound care but also routine diabetes surveillance, as a vital service during national health emergencies. The emergency shift of outpatient services to inpatient settings and the allocation of staff to those settings affected preventive podiatric foot care. These regular high-risk foot screenings and patient education in the outpatient setting can allow for early identification and prevent complications. The increase in all levels of amputation during the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the restrictions, highlights the need for wound care in limb salvage efforts. The decrease in WDBs, INDs, and EXOs was likely secondary to the delay in seeking treatment, leading to more amputations. The sharp increase in mortality at the start of the pandemic and the subsequent decrease emphasize the effects of COVID-19. Little research has been conducted on the reasons for the increase in amputations following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, more focused research is needed. The most accepted hypothesis is the need for follow-up care.

Limitations

While the number of wound-related surgeries performed at the hospital in this study is significant, its limitations include a focus on a single institution. The number of all procedures in 2020 and 2021 is likely lower than it should be due to factors such as fear of attending clinic visits, access issues, patients relocating to different areas, and unreported mortality.

Conclusions

Research into the long-term effects of COVID-19 infection is ongoing. Further research into the effect of decreased comorbidity follow-up during the pandemic, such as routine diabetes, peripheral artery disease, and neuropathy management, could aid in understanding the continued increase in DAMs. There is also a need to do better in order to reduce the disparities seen in DFUs and the amputation rate in ethnic minority groups. The data in this study highlight how these marginalized groups were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 restrictions. Further research into these ethnic minority groups’ socioeconomic status, access to health care, education, language, and cultural barriers could be crucial in the health care system. The data from the present study suggest that health institutions like the one studied herein would benefit from policy changes surrounding diabetes education and care in ethnic minority populations and from equipping health care providers with better telemedicine services. These strategies would be vital should a pandemic like COVID-19 arise again.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Hau Pham, DPM; Ewald Mendeszoon, DPM; Vitaliy Volansky, DPM; Justin Ogbonna, DPM; Wei Tseng, DPM; Elizabeth Sanders, DPM; David Coker, DPM; and Ashley Daniel, DPM, MBS

Affiliation: Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA

Acknowledgments: Dr Daniel Reubens, a podiatric resident during the pandemic (from July 1, 2018, to June 30, 2021), reviewed transmetatarsal amputations and the effect of COVID-19. The current authors expanded on this and reviewed all wound-related procedures for a longer time frame.

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: The institutional review board of the authors’ institution accepted the review and granted it exempt status.

Correspondence: Hau Pham, DPM; Boston Medical Center, 732 Harrison Ave, Boston, MA 02118; Hau.pham@bmc.org

Manuscript Accepted: April 28, 2025

References

1. Armstrong DG, Tan TW, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic foot ulcers: a review. JAMA. 2023;330(1):62-75. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.10578

2. World Health Organization. Situation Report – 10: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/situation-report---10

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, February 7, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 7, 2020. 69(5);140–146. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/pdfs/mm6905-H.pdf

4. World Health Organization. Situation Report – 22: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/situation-report---22

5. World Health Organization. Situation Report – 51: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). World Health Organization, 2020.

6. Poulose BK, Phieffer LS, Mayerson J, et al. Responsible return to essential and non-essential surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;25(5):1105–1107. doi:10.1007/s11605-020-04673-9

7. Jacobsen GD, Jacobsen KH. Statewide COVID-19 Stay-at-home orders and population mobility in the United States. World Med Health Policy. 2020;12(4):347-356. doi:10.1002/wmh3.350

8. Pride L, Kabeil M, Alabi O, et al. A review of disparities in peripheral artery disease and diabetes-related amputations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Semin Vasc Surg. 2023;36(1):90-99. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2022.12.002

9. Winter Beatty J, Clarke JM, Sounderajah V, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency adult surgical patients and surgical services: an international multi-center cohort study and department survey. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):904–912. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000005152

10. Hussain A, Bhowmik B, do Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: knowledge in progress. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108142

11. Bornstein SR, Rubino F, Khunti K, et al. Practical recommendations for the management of diabetes in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(6):546–550. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30152-2

12. Rogers LC, Lavery LA, Joseph WS, Armstrong DG. All feet on deck – the role of podiatry during the COVID-19 pandemic: preventing hospitalizations in an overburdened healthcare system, reducing amputation and death in people with diabetes. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2023;113(2):20-051. doi:10.7547/20-051

13. Shin L, Bowling FL, Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM. Saving the diabetic foot during the COVID-19 pandemic: a tale of two cities. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):1704-1709. doi:10.2337/dc20-1176

14. Steed DL, Attinger C, Colaizzi T, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of diabetic ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14(6):680-92. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00176.x

15. Lipsky BA, Senneville É, Abbas ZG, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of foot infection in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36 Suppl 1:e3280. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3280

16. Conte MS, Bradbury AW, Kolh P, et al. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(6S):3S-125S.e40. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2019.02.016

17. Griffin KJ, Rashid TS, Bailey MA, et al.. Toe amputation: a predictor of future limb loss? J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26(3):251-254. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.03.003

18. Molina CS, Faulk JB. Lower Extremity Amputation. [Updated 2022 Aug 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546594/

19. Rogers LC, Snyder RJ, Joseph WS. Diabetes-related amputations during COVID-19: a pandemic within a pandemic. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2023;113(2):20-248. doi:10.7547/20-248

20. Casciato DJ, Yancovitz S, Thompson J, et al. Diabetes-related major and minor amputation risk increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2023;113(2):20-224. doi:10.7547/20-224

21. Ergişi Y, Özdemir E, Altun O, et al. Indirect impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on diabetes-related lower extremity amputations: a regional study. Jt Dis Relat Surg. 2022;33(1):203-207. doi:10.52312/jdrs.2022.564

22. Liu C, You J, Zhu W, et al. The COVID-19 outbreak negatively affects the delivery of care for patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(10):e125–e126. doi:10.2337/dc20-1581