Trends in Vascular Surgery Activity: Results From the Spanish National Inpatient Registry Over an 18-Year Period (2005 to 2022) and Future Plan

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Vascular Disease Management or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

VASCULAR DISEASE MANAGEMENT. 2025;22(10):E82-E87

Abstract

Purpose. In this manuscript, the authors aim to identify the main trends in diagnosis, procedures, and costs of angiology and vascular surgery in Spain over a period of 18 years, with a time horizon in 2035. Methods. In this retrospective observational population-based study, data from the Spanish Minimum Basic Data Set were reviewed. All vascular patient hospitalizations reported from 2005 to 2022 were analyzed. Age and sex-adjusted incidence rates were calculated for all diagnostics and procedures. Generalized linear models were used for trend analysis. Results. Between 2005 and 2022, the adjusted rate of diagnostics in vascular surgery departments increased from 102.5 per 100,000 population in 2005 (confidence interval [CI],95%: 101.5-103.4) to 237.1 per 100,000 population (CI, 95%: 235.7-238.4) in 2022. The annual linear trend in total rate of diagnosis estimated shows a similar increase in all groups, with no interaction effect by sex or age (inter-rater reliability [IRR] = 1.02; CI, 95%: 1.01-1.04, P = .001). The adjusted rate of procedures reported in vascular surgery departments increased from 215.4 per 100,000 population (CI, 95%: 214.0-216.8) in 2005 to 521.7 (CI, 95%: 519.7-523.7) in 2022. The annual linear trend in total rate of procedures estimated was higher in groups under age 64 (P = .001), with no interaction effect by sex: IRR = 1.05 (CI, 95%: 1.04-1.07) in men and 1.07 (CI, 95%: 1.05-1.10) in women, while in groups over age 64, IRR = 1.01 (CI, 95%: 0.99-1.03) and 1.03 (CI, 95%: 1.01-1.05), respectively. The mean of all patient refined costs in 2016 was $4929.09 (€4200.44) and in 2022 was $5711.78 (€4867.43). The estimated annual increase adjusted by age and sex was $156.49 (€133.36) (CI, 95%: -2.60 to 269.30, P = .054). Conclusions. In Spain, despite the advances that have taken place in controlling vascular risk factors, the incidence rate of diagnosis and vascular procedures increased regardless of age and sex. Recommendations to face the growing demand and complexity of vascular surgery services include a yearly growth of the health care workforce until 2035 and the development and application of more accurate quality indicators for measuring vascular care and health outcomes.

Introduction

Globally, healthcare professionals, stakeholders, and politicians involved in the development of health policies and health workforce planning are facing a variety of challenges.1,2 Health care workforce shortages are some of the biggest and most pressing challenges.3 Despite economic development and technological progress, many countries are still struggling with staff shortages. The trends are worrying, as health care professionals are aging and there are insufficient efforts to replace retiring professionals. The World Health Organization predicts an increase in the global demand for social and health care workers, estimating that there will be 40 million new health jobs created by 2030.4,5

Nevertheless, cardiovascular diseases are still one of the main concerns in Spain, as it is the leading cause of death and disability adjusted life years lost in men and in women.6 In Spain, 26.4% of deaths in 2021 were due to diseases of the circulatory system, 25.2% to tumors, and 10.2% to infectious diseases.7

The increase in the incidence of vascular diseases, the decrease in mortality rates, and the aging of the population are causing an increase in the number of potential vascular patients who will demand diagnostic and treatment services at angiology and vascular departments in the coming years.

Health workforce shortages are conditioned by many factors; however, in order to plan and implement mitigating actions, it is necessary to acquire information on how large these shortages are and what the demands are. Unfortunately, in many countries, there is a lack of strategic planning based on the analysis of the health labor market, exacerbated by the lack of reliable data and information necessary to implement effective human resources policies in health care. The collection and subsequent analysis of data usually take time, so the data that are published correspond to previous years or are incomplete.

In addition, the incidence of vascular diseases in Spain continues to increase,7 due in part to the aging of the population, environmental factors, and certain lifestyles in society today.

Human resource planning for health is extremely important and widely discussed, which is why many scientists attempt to collect the best and most recent data and make them available to interested audiences.

To adequately respond to the challenges of the specialty, it is essential to monitor potential medical vascular workforce shortages.

The main objective of this study was to analyze trends in diagnosis, procedures, and costs of activity on services at angiology and vascular departments in Spain over a period of 18 years to identify trends in the future needs of specialists.

Materials and Methods

Design

A retrospective observational population-based study was conducted.

Data Source

For this study, the Spanish national information system Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS) of hospital discharges during the period between 2015 and 2022 was used. This database is created through the coding of hospital discharge reports. Data must be provided by all Spanish hospitals, both public and private, and are estimated to cover 98% of the Spanish population.8 For the study period (2005-2022), it contains data on approximately 60 million hospital discharges.9

In addition to demographic data (age, sex, and place of residence), the MBDS includes the diagnosis leading to hospital admission (primary diagnosis) as well as any surgical procedures performed.8

Data collected are coded in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9-CM/PCS) from 2005 to 2016, and the ICD-10-CM/PCS from 2016 to 2022.

Our data include the number of diagnostics, procedures, and costs in total and by sex and age group (< age 64, > age 64) of 108 angiology and vascular departments. To calculate rates, Spanish population data by sex and age group were provided by the national census (National Statistics Institute of Spain).

The Registry of Specialized Health Care Activity (RAE-CMBD) integrates administrative and clinical information on patients treated in different specialized care modalities, giving continuity to the CMBD but expanding, since 2016, its coverage to outpatient care modalities and the private sector. The rules for the registration and sending of data are established in Royal Decree 69/2015 that creates the RAE-CMBD. The statistical exploitation of these data is included among the operations of the National Statistical Plan.

In 2015, data from the Spanish Hospital Cost Network were available for the first time, thus serving as a basis for the development of predictive cost models and their extension to the clinical care data of the Spanish National Health System (SNHS) general hospitals.

Costs have been estimated with data of analytic accounting systems for a representative sample of Spanish public hospitals, and include all running costs.

Thus, in 2016 the weights and costs of the SNHS were published, both for the All Patient Diagnosis Related Group v27 grouping system and for All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG) v32. The APR-DRG costs suppose a more refined classification of the hospital casuistry, offering information in each case on the severity of the disease and the risk of mortality of the patient and its impact on the cost of the service.10

As a result of this process, in 2016 it was possible to publish for the first time some weights and costs of the SNHS based entirely on our own costs and on the actual care practice of our system.

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Statistical Methods

Crude and age-sex adjusted rate per 100,000 habitants (h) by direct method were computed. The direct method of adjusting for differences among populations involves computing the overall rates that would result if, instead of having different distributions, all populations had the same standard distribution. The standardized rate is defined as a weighted average of the stratum-specific rates, with the weights taken from the standard distribution. With the aim of estimating the number of diagnostics, procedures, and costs that will make the angiology and vascular surgery workforce in Spain with a time horizon to 2035, predictive multivariate Poisson regression models were adjusted, with numbers of diagnostics and procedures as dependent variables and year, sex, and age group (< age 64, > age 64) as predictor variables; population data were included as exposure variables.

Linear regression models were used, with APR costs as dependent variables. The models included the first level interaction with year. Linear trends expressed as IRR in the total sample and by groups defined by sex and age were estimated with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Predictions from 2022 to 2035 were performed using the 2022 standardized rate and linear trends estimated with models.

A P-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 17 software.

Results

Abbreviation: hab = habitants.

Diagnostics Annual Trends

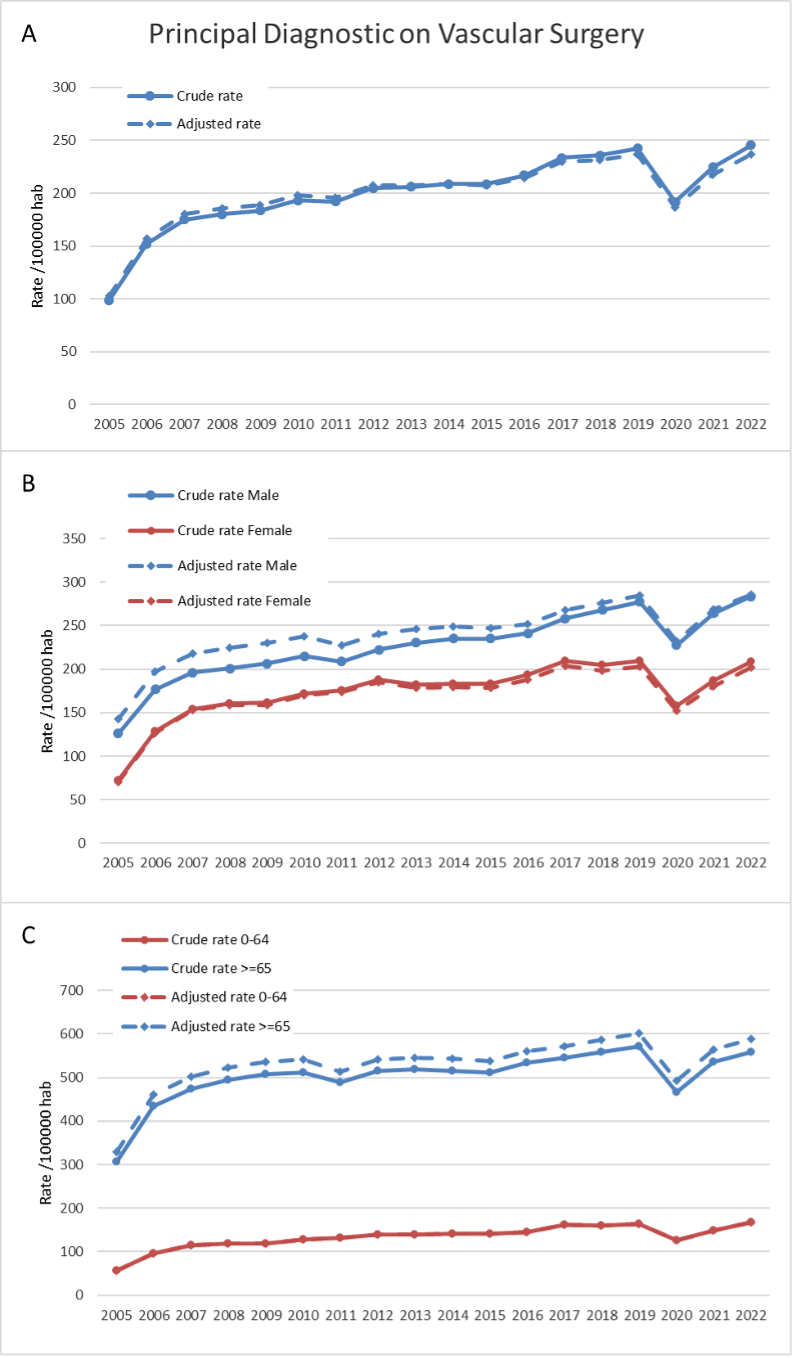

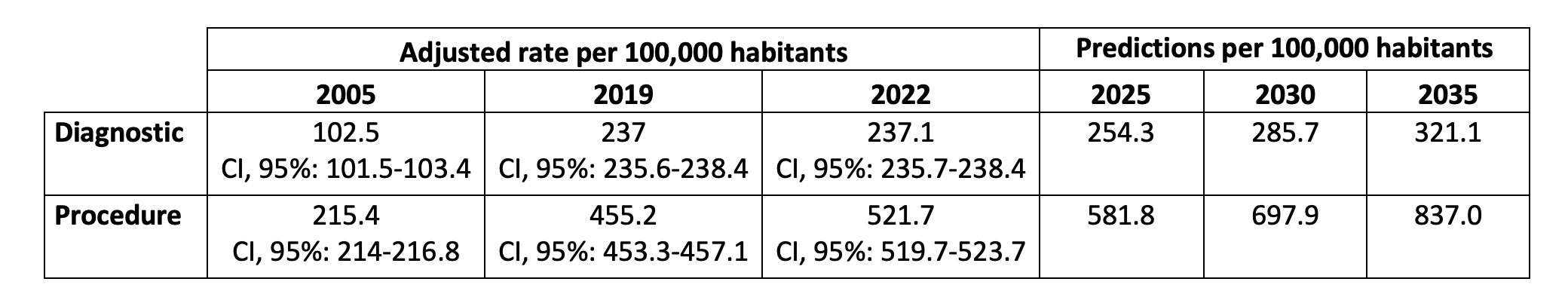

The adjusted rate of diagnostics in vascular surgery departments increased from 102.5 per 100,000 h (CI, 95%: 101.5-103.4) in 2005 to 237.1 per 100,000 h (CI, 95%: 235.7-238.4) in 2022 (Figure 1A). Similar trends were seen according to sex (Figure 1B) and age (Figure 1C).

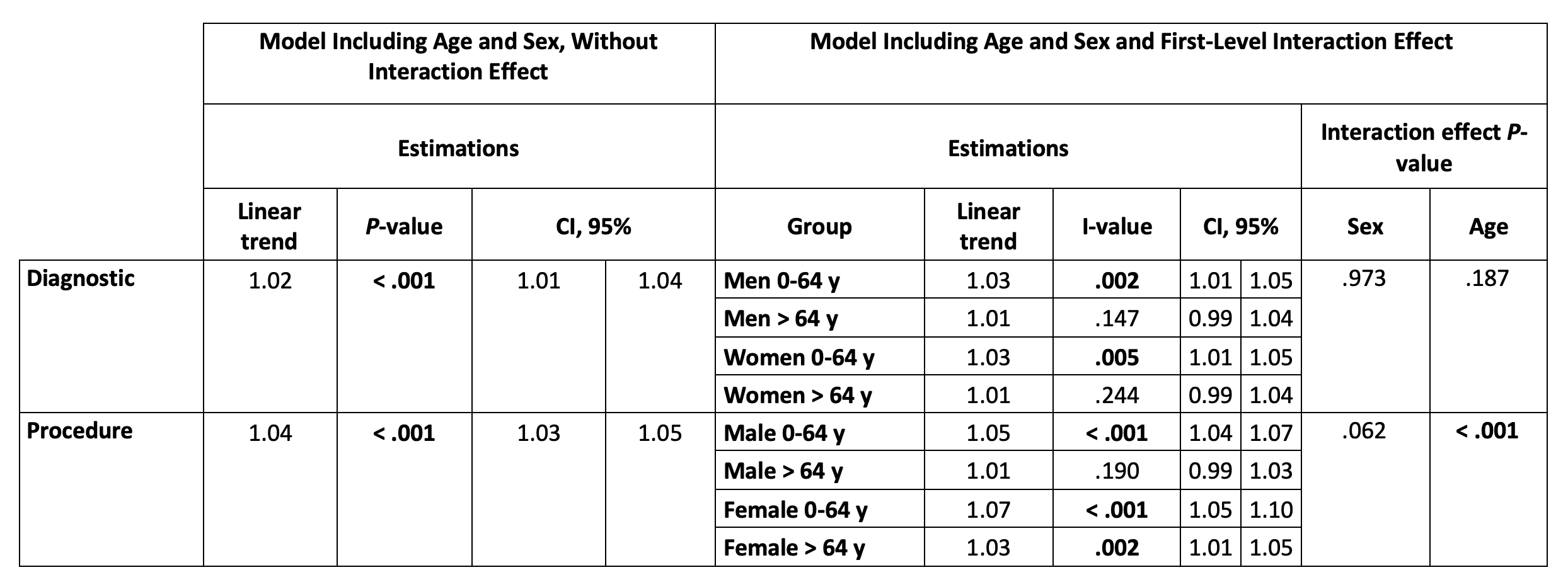

The annual linear trend in total rate of diagnosis estimated with Poisson models shows a similar increase in all groups, with no interaction effect by sex or age: IRR = 1.02 (CI, 95%:1.01-1.04, P = .001) (Table 1).

Procedure Annual Trends

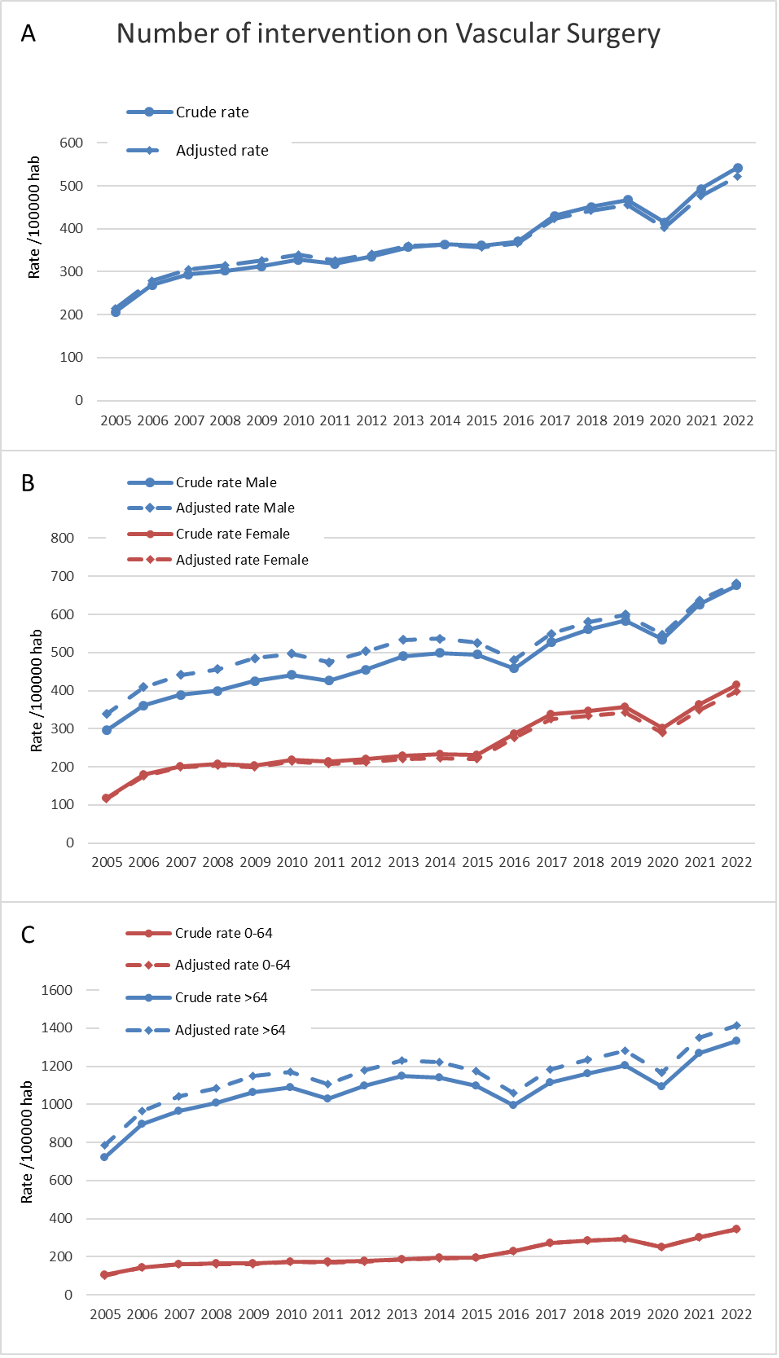

The adjusted rate of surgeries reported in vascular surgery departments increased from 215.4 per 100,000 h (CI, 95%: 214-216.8) in 2005 to 521.7 per 100,000 h (CI, 95%: 519.7-523.7) in 2022 (Figure 2A). Similar trends were seen in men and women (Figure 2B), but higher in ages over 64 than under 64 (Figure 2C).

Abbreviation: hab = habitants.

The annual linear trend in total rate of procedures estimated with Poisson models was higher in the under age 64 groups (P = .001), with no interaction effect by sex: IRR = 1.05 (CI, 95%: 1.04-1.07) in men and 1.07 (CI, 95%: 1.05-1.10) in women, while in over age 64 groups IRR = 1.01 (CI, 95%: 0.99-1.03) and 1.03 (CI, 95%:1.01-1.05), respectively (Table 1).

Activity and Cost Projected Trends

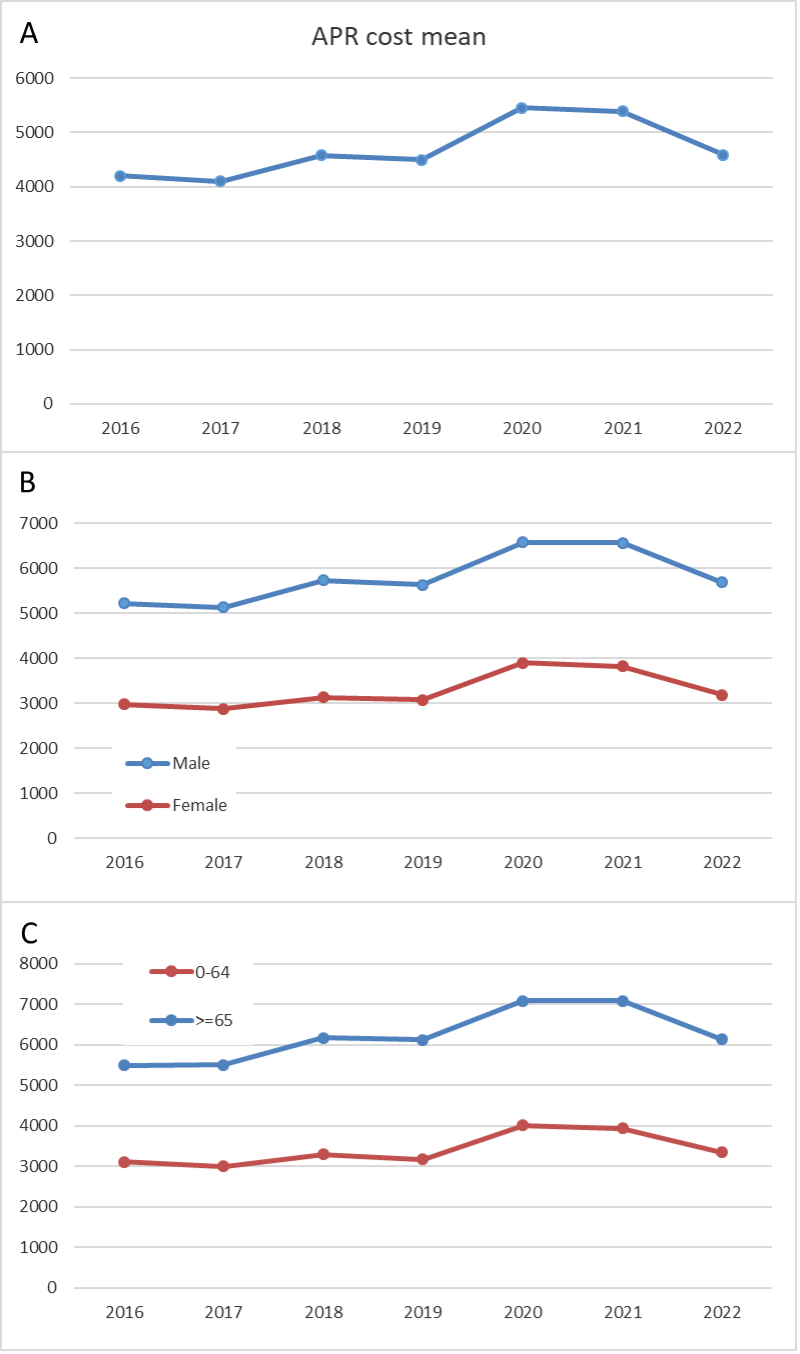

The mean APR cost in 2016 was $4929.09 (€4200.44) (the mean annual cost per discharge in vascular departments), and in 2022 was $5711.78 (€4867.43) (Figure 3).

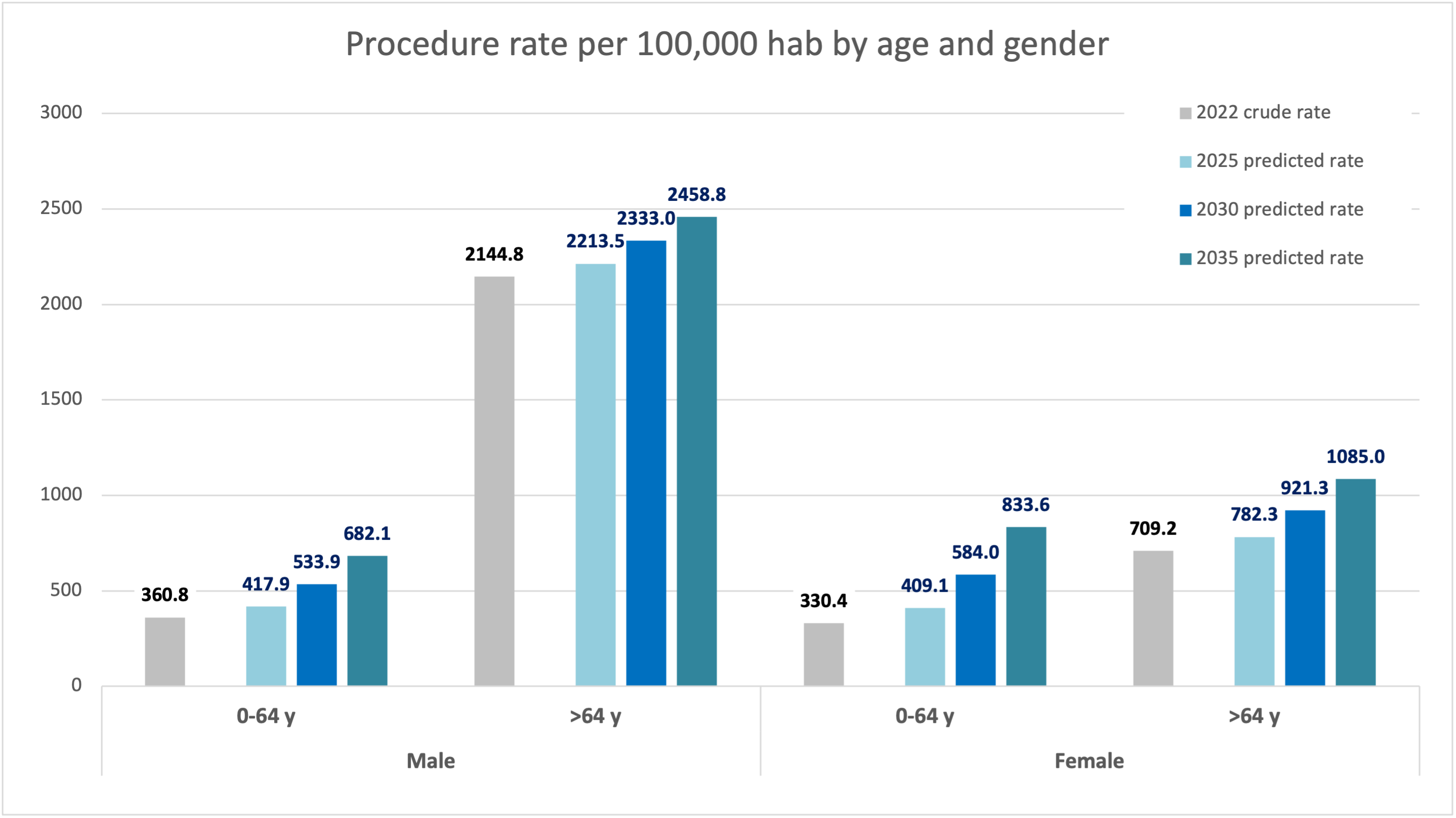

The annual increase estimated adjusted by age and sex was $156.49 (€133.36) (CI, 95%: -2.6 to 269.3, P = .054). The mean of costs predicted in the general population are $7417.85 (€6334.60) in 2030 and $8491.64 (€7251.58) in 2035, adjusted by age and sex (Figure 4).

The rate of cases predicted would attain 285.7 per 100,000 h diagnostic cases in 2030 and 321.1 per 100,000 h diagnostic cases in 2035. The rate of procedures in 2030 will be 697.9 per 100,000 h and 837 per 100,000 h in 2035. (Table 2, Figure 4).

Discussion

Each year, cardiovascular disease causes 3.9 million deaths (45% of all deaths) in Europe and over 1.8 million deaths (37% of all deaths) in the European Union. It is the main cause of death in men in the majority of European countries and the main cause of death in women in all but 2 countries.11

In this study, we performed countrywide analysis over a long period of time (2005-2022), enabling us to assess the trends in vascular diagnosis and procedures in patients admitted to hospitals in Spain. The main objective was to evaluate historic trends of vascular diagnosis and procedures and perform a projection to 2035 on vascular diseases in Spain.

Our main findings are: First, in our study, the trend of vascular diagnosis had an increased incidence of 134.6 per 100,000 h (from 102.5 to 237.1) from 2005 to 2022, similar for age and sex. This represents an increase of 131% compared with the initial situation (2.31 times).

Second, the adjusted rate of surgeries reported in vascular surgery departments increased 306.3 per 100,000 h (from 215.4 to 521.7) from 2005 to 2022, with similar trends in men and women and according to age. This represents an increase of 142% compared with the initial situation (2.42 times).

Third, the predicted rate of diagnosis for 2035 is more than triple than in the initial year. According to the model, the procedures rate will be 837 per 100,000 h in 2035 (3.9 times more procedures than in the initial year).

Fourth, this increase in vascular disease would impose a cost increase from $4929.09 (€4200.44) in 2016 to $8491.64 (€7251.58) APR cost per year in 2035 (an increase of 170% higher than the initial situation and an increase of 155.7% from 2022).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the vascular diagnostic and procedures rate trend.

The overall rate of procedures was higher in people over age 64 for both sexes (men > age 64 grow an IRR of 1.01 and women 1.03), but we observed a greater increase of procedures in those under age 64 (men grow IRR 1.05 and women 1.07) (P < .001). This could be associated with an increase in cardiovascular risk factors in young people, and in the case of young women it could be due to an increase in venous procedures, which is a reason for our next study.13,14

These results have important economic consequences for the SNHS and for private health insurance companies, as by 2035 the cost would be increased from $4929.09 (€4200.44) APR cost per year in 2016 to $8491.64 (€7251.58) APR cost per year.

We believe that the length of the study period and the exhaustive data provided by the MBDS provide sufficient internal validity, as all hospitalizations are included for the whole country, covering both public and private centers as well as all surgical procedures, including ambulatory ones. The disaggregation of the data by age and sex allowed us to calculate population rates for the different demographic groups.

Lastly, some mention should be given to the study’s limitations, as somewhat intimated above, regarding prediction. Despite the flexibility of generalized linear models the predictive ability over 20 years must be tempered by what else could happen. Procedures and medicine will change, and while things almost invariably become more expensive, it must be remembered how wrong our predictions have been in the past. What may or may not happen does not require lengthy expostulation but, when juxtaposed with a well-described analysis of what challenges are upon us, these types of considerations can both increase interest and provoke further discussion.

Finally, this analysis is not full until we also analyze the total population of Spain, and the official population projections for the period 2022 to 2070, as well as the feminization or aging of our specialty to the needs of vascular surgeons in Spain and the needs of specialists in 2035.

The present study has both major strengths and limitations: Some limitations are inherent in the data, although the MBDS provides information from a network of hospitals covering more than 98% of the Spanish population.9 It is possible that some cases may have not been captured by the public registry of hospital discharges and there may have been some coding errors. We assumed that the missing patients (not included in the study) have the same epidemiological and demographic characteristics as the included ones. Specifically, we assume that the diagnostic codes and surgical procedures are distributed among the missing patients similarly to the included patients.

Although we have analyzed data until 2022, we have to consider the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our health care system in 2020. In 2020, all health care, except for care specifically focused on COVID-19, suffered a transitory drop. Therefore, the figures for programmed diagnostic and intervention activities in 2020 are exceptionally low.

Conclusions

This nationwide study shows that there is an upward trend in the incidence of vascular diagnosis in Spain, both in men and in women. There is also an increase in vascular procedures in people under age 65 in both men and women.

According to the model's prediction, in 2035 there will be 35% more diagnoses and 60% more interventions in the specialty of vascular surgery than in 2022, and the total cost of these procedures will have increased by 56%. n

REFERENCES

1. Health and care workforce in Europe: time to act. World Health Organization; 2022. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289058339

2. Tomblin Murphy G, Birch S, MacKenzie A, Bradish S, Elliott Rose A. A synthesis of recent analyses of human resources for health requirements and labour market dynamics in high-income OECD countries. Hum Resour Health. 2016;4(1):59. doi:10.1186/s12960-016-0155-2

3. Kuhlmann E, Batenburg R, Wismar M, et al. A call for action to establish a research agenda for building a future health workforce in Europe. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):52. doi:10.1186/s12961-018-0333-x

4. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. World Health Organization; 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511131

5. High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth. Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce. World Health Organization; 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511308

6. Main causes of death (adjusted by death) between sex and autonomous community. Ministerio de Sanidad; 2023. https://www.sanidad.gob.es/fr/estadEstudios/sanidadDatos/tablas/tabla3.htm.

7. Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. https://www.ine.es.

8. Bernal-Delgado E, García-Armesto S, Peiró S, Atlas VPM Group. Atlas of variations in medical practice in Spain: the Spanish National Health Service under scrutiny. Health Policy. 2014;114(1):15-30. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.07.013

9. Application for the analysis and exploitation of RAE_CMBD. Ministerio de Sanidad. https:// icmbd.sanidad.gob. es/icmbd/login-success.do

10. Proceso de estimación de pesos y costes hospitalarios del SNS. Goberierno de España/Ministerio de Sanidad; 2022. https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/CMBD/2020_nota_metodologica_costes.pdf

11. CVD statistics. European Heart Network; 2017. https://ehnheart.org/about-cvd/the-burden-of-cvd

12. Piessens V, Heytens S, Van Den Bruel A, Van Hecke A, De Sutter A. Do doctors and other healthcare professionals know overdiagnosis in screening and how are they dealing with it? A protocol for a mixed methods systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e054267. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054267

13. GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223-1249. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2

14. Spain, Quick Facts. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2021. https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/health-by-location/profiles/spain?language=41

Affiliations and Disclosures

Sandra Vicente-Jiménez, MD, is from the Angiology and Vascular and Endovascular Department, Alcorcón University Foundation Hospital, Madrid, Spain, and the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canarias, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; Elia Perez-Fernández, MD, is from the Investigation Unit, Fundación de Alcorcón, University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; Carlos Maria Elvira-Martinez, MD, is from the Admission and Clinical Documentation Department, Clínico San Carlos University Hospital, Madrid, Spain; Patricia Lucia Barber-Pérez, MD, Manuel Maynar, MD, and Beatriz Gonzalez Lopez-Valcarcel, MD are from the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canarias, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; and Luis de Benito, MD, is from the Angiology and Vascular and Endovascular Department, Alcorcón University Foundation Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Manuscript accepted August 25, 2025.

Address for Correspondence: Sandra Vicente-Jiménez, Vascular Surgery Department, Alcorcón University Foundation Hospital, Av. Budapest 1, 28922 Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain. E-mail: sandravj1984@gmail.com