Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia: Are We Saving Limbs but Losing Lives?

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Vascular Disease Management or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

VASCULAR DISEASE MANAGEMENT. 2025;22(11):E92-E98

Abstract

Chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) is a manifestation of end-stage atherosclerosis with high risk for limb loss and loss of life. Surgical and endovascular treatments to restore blood flow to the lower extremity are effective in reducing the risk of amputation. However, mortality following successful lower-extremity revascularization is alarmingly high, with 20% of patients dead in 1 year and 70% dead in 5 years. The primary cause of death is coronary artery disease (CAD), which is often asymptomatic due to a limited ability to walk. Current guideline-directed management of cardiac risk in CLTI patients is best medical therapy and atherosclerotic risk factor control with no cardiac testing of patients without cardiac symptoms. This strategy has been ineffective in reducing the high mortality rate. In this article, we consider a new strategy based on noninvasive cardiac testing using coronary computed tomography angiography to identify patients with silent coronary ischemia, which is a marker for risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and sudden cardiac death. Ischemia-guided coronary revascularization has been shown to reduce the risk of death and MI in CAD patients, and this has now been utilized in patients with CLTI in order to improve long-term survival.

Introduction

Chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI), defined by ischemic foot pain at rest, nonhealing ulcerations, or gangrene, is the most severe manifestation of peripheral arterial disease (PAD).1 Patients with CLTI are at high risk for limb loss and require prompt lower-extremity revascularization (LER) to avoid amputation. They are also at increased risk of death due to coexisting coronary artery disease (CAD), which is often asymptomatic and unrecognized. Patients with CLTI may not experience chest pain symptoms due to a limited ability to walk or diabetes mellitus. In major prospective randomized trials of patients with CLTI undergoing LER, more than 50% have no known CAD at baseline, and at 5 years more than 50% have died due to CAD.2,3 In a population-based study of almost 100,000 patients in the Danish national registries, patients with first hospitalization for CLTI were compared to patients with first hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction (MI).4 In both groups, 80% of patients had no known CAD at baseline. At 3 years, 40% of patients with CLTI had died while only 20% of patients with acute MI died.4 The twofold higher mortality of patients with CLTI was attributed to low use of evidence-based best medical therapy (BMT) while ignoring the fact that patients with acute MI are typically treated with coronary revascularization in addition to BMT. It is more likely that the high mortality of patients with CLTI was related to unrecognized and untreated coexisting CAD. This article focuses on these apparently “good risk” patients with CLTI with no known CAD (no cardiac history, no prior MI, and no chest pain symptoms) who are expected to have good survival following LER.1

Are We Saving Limbs but Losing Lives?

There is no doubt that we are saving limbs with timely diagnosis of CLTI and treatment with LER. LER is effective in saving limbs by restoring arterial circulation to the foot and avoiding the need for amputation. Successful restoration of pulsative blood flow to the foot has a dramatic effect on tissue perfusion, relieving symptoms and preventing amputation. However, we are losing lives due to coexisting CAD, which is often asymptomatic, undiagnosed, and untreated due to the absence of chest pain symptoms. Within 1 year following successful LER, 20% of patients will have died,5 and within 5 years, 2 of 3 patients (70%) will have died.6 This alarming mortality rate is higher than for acute MI and most cancers.5 The risk of death is 3 to 4 times higher than the risk of amputation, and the primary cause of death is coexisting CAD.3 The annual mortality rate for patients undergoing LER is 10% to 12% per year, the same as it was 4 decades ago. This is in sharp contrast to the marked decline in annual mortality for patients with symptomatic CAD to 1% to 2% per year, in association with coronary revascularization as a mainstay of treatment.7

Historical context

Forty years ago, the high prevalence of CAD in patients with PAD and the potential benefit of coronary revascularization in reducing the mortality of vascular surgery patients were first brought to light by Hertzer, et al in a landmark study of 1000 coronary angiograms prior to elective vascular surgery.8 This study showed that 60% of patients had more than 70% coronary stenosis and that 45% had no symptoms of CAD. Elective coronary artery bypass grafting, the only method of coronary revascularization at that time, significantly improved 5- and 10-year survival of patients undergoing vascular surgery.8 However, the strategy of coronary revascularization to improve the survival of patients with PAD fell by the wayside 20 years ago with publication of the Coronary Artery Revascularization Prophylaxis (CARP) trial.9 This study randomized 510 patients with angiographic coronary stenosis greater than 70% undergoing peripheral or aneurysm surgery to preoperative coronary revascularization or no coronary revascularization. At 2.7 years, there was no difference in all-cause mortality (23% in both groups), and the authors concluded that “a strategy of coronary artery revascularization before elective vascular surgery among patients with stable cardiac symptoms cannot be recommended.”9 This randomized study has had a major longstanding impact on the management of CAD in patients with PAD both before and after vascular surgery procedures. Current PAD guidelines, while acknowledging the high cardiac-related risk in patients with PAD, recommend no preoperative cardiac testing of patients without cardiac symptoms because it will not change patient management, citing the 20-year-old CARP trial as evidence that coronary revascularization does not improve long-term survival.10 All patients should simply be treated with BMT and risk-factor control to minimize cardiac risk. Coronary revascularization should be considered only in patients who develop cardiac symptoms or in those who experience an acute cardiac event such as an MI.

Outdated relevance of the CARP trial

It should be noted that the CARP trial is now outdated primarily due to significant advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CAD. Coronary revascularization is no longer based on visual estimates of angiographic percent stenosis alone but requires evidence of functionally significant stenosis.11 Hemodynamic significance of coronary lesions can be determined invasively by measuring fractional flow reserve (FFR) in the cath lab or noninvasively using computational methods applied to coronary computed tomography angiography data (FFRCT).12 Ischemia-guided coronary revascularization has been shown to reduce death and MI and improve long-term survival in patients with CAD compared to BMT and is now the standard of care for coronary revascularization.13

Thus, while we are saving limbs by timely diagnosis and treatment of lower-extremity ischemia, we may be losing lives by failing to diagnose and treat coexisting CAD, which is the primary cause of death in patients with PAD.

Is BMT Good Enough?

Guideline-recommended medical management of cardiac risk in patients with PAD is mainly derived from a large body of randomized trial evidence in patients with CAD, some of which include subsets of patients with PAD. While the overall benefit of BMT and risk-factor control is well documented, evidence specific for patients with PAD is lacking. The VOYAGER PAD trial is the only randomized trial that was specifically focused on medical therapy in patients with PAD following LER (primarily claudicants). Rivaroxaban was effective in reducing the composite endpoint of acute limb events and cardiovascular events (P < .01), primarily due to a reduction in limb events. However, there was no reduction in cardiovascular death or MI.14

While guidelines stress the importance of BMT in reducing cardiac risk, there is no randomized trial evidence showing the effectiveness of BMT in reducing death or MI. This does not suggest that optimal medical therapy is of no value in management of CAD, but rather that a new strategy is needed to address the problem of high mortality in patients with PAD due to coexisting CAD. BMT alone is not good enough.

New Guidelines for Evaluation of Suspected CAD

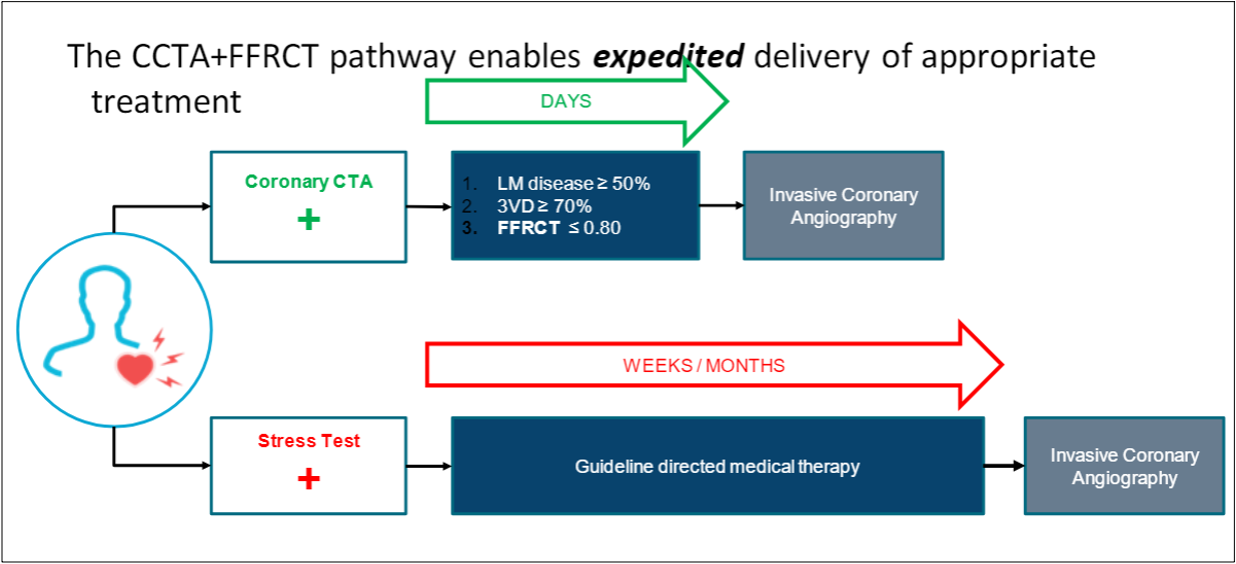

The 2021 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain highlighted as the top takeaway message, “Chest pain is more than pain in the chest.”15 Patients with CAD most often present with symptoms other than anginal chest pain, particularly women. Symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea, and nausea are anginal equivalents, and patients with such symptoms should be suspected of having CAD The current guideline-recommended pathway for intermediate-high risk patients with “suspected CAD” and no known CAD is (1) coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) for the diagnosis of CAD (Class 1A) and (2) FFRCT for patients with 40% to 90% coronary stenosis to diagnose coronary ischemia and to guide decision-making regarding the use of coronary revascularization (Class 2a) (Figure 1).15

Patients with CLTI are certainly high-risk patients, and they often have symptoms of fatigue and dyspnea in addition to a limited ability to walk, which should lead one to suspect CAD. Despite a lack of chest pain symptoms, patients with PAD often have unsuspected “silent coronary ischemia,” which is a marker for sudden cardiac death or acute MI.16 Thus, patients with CLTI should be suspected of having CAD and evaluated accordingly.

A New Strategy for Managing CAD in CLTI

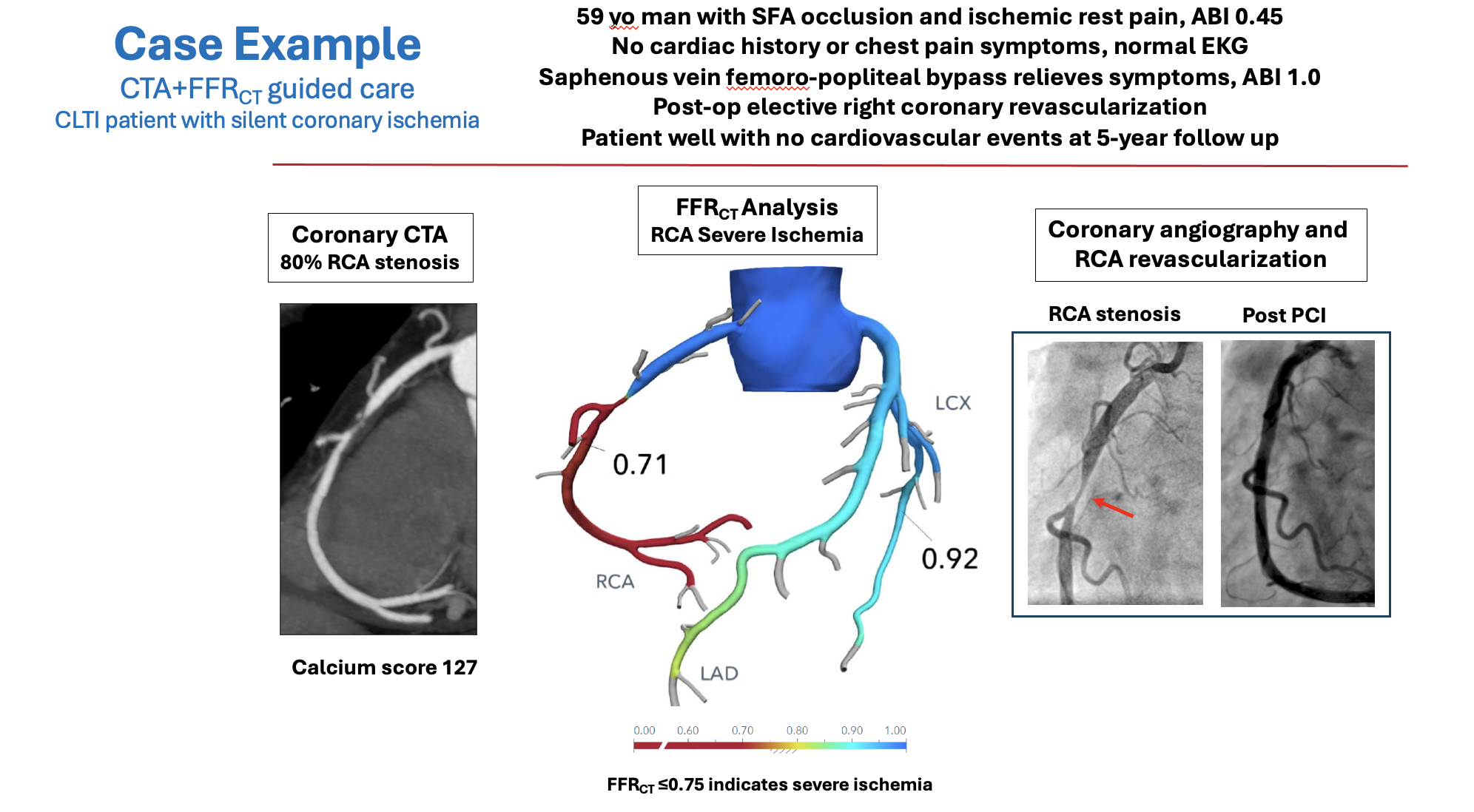

Consistent with the new cardiac evaluation guidelines, we propose a new strategy for managing CAD in patients with CLTI based on (1) diagnosis of silent coronary ischemia and (2) ischemia-targeted coronary revascularization to reduce the risk of adverse cardiac events and improve long-term survival. The diagnosis of coronary ischemia is made using coronary CTA and FFRCT. This can identify patients with high-risk, ischemia-producing lesions and differentiate them from patients without coronary ischemia who have a favorable long-term prognosis. Coronary revascularization can be performed on an elective basis after treatment of lower-extremity ischemia, with a focus on restoring coronary blood flow to normal. This strategy has been applied to patients with CLTI and no known CAD in a single-center, prospective, Institutional Review Board-approved study. A case example is shown in Figure 2.

High Prevalence of Silent Coronary Ischemia in CLTI

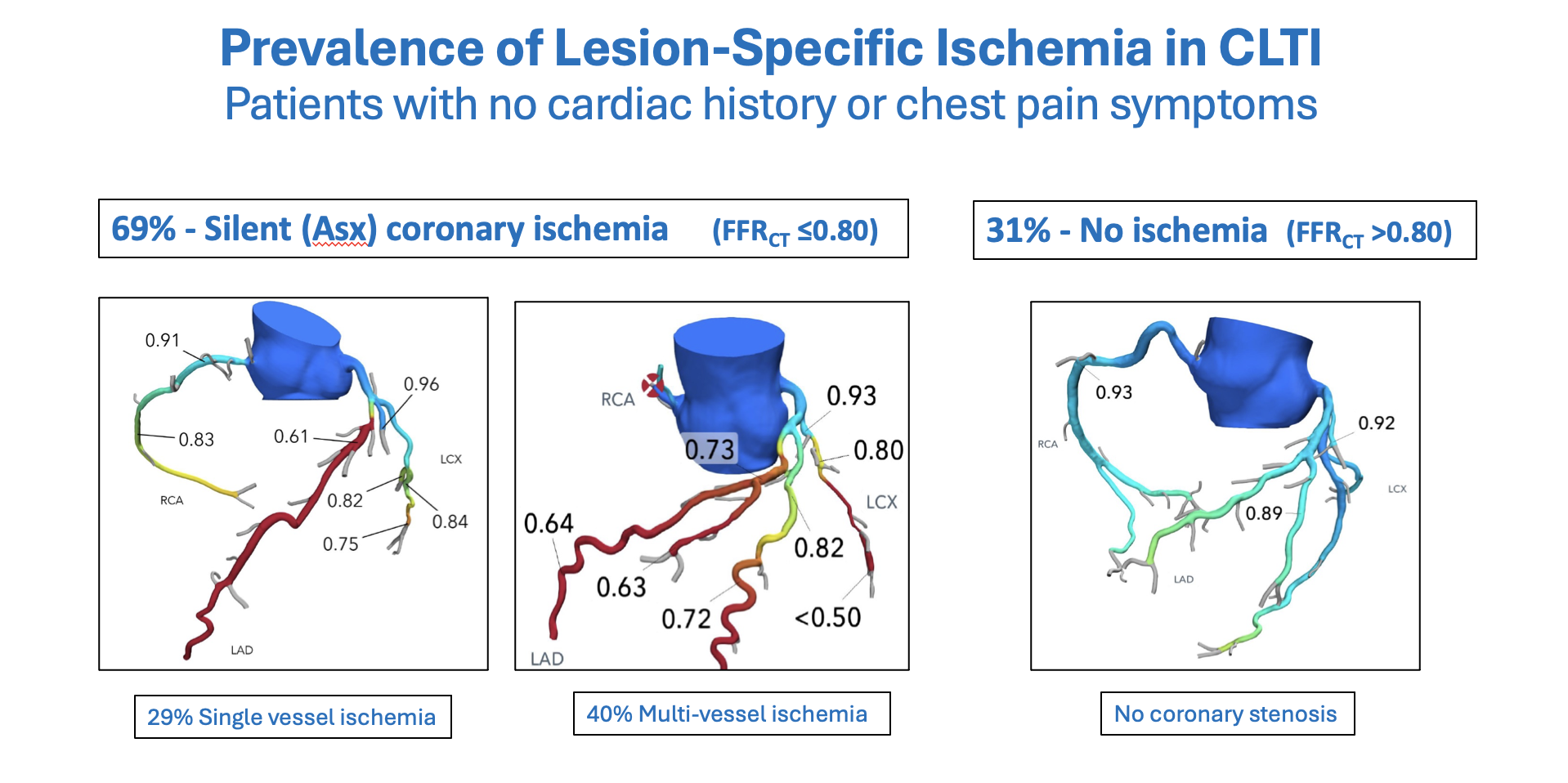

The first report of systematic preoperative cardiac evaluation included 54 patients with CLTI and no cardiac history or chest pain symptoms. Coronary CTA + FFRCT imaging revealed that 2 of 3 patients (69%) had unsuspected, silent coronary ischemia (FFRCT ≤ 0.80 distal to a stenosis).17 This was an unexpected finding because all patients were free of cardiac symptoms and all had been cleared for elective LER in accordance with guidelines. The LER procedures were performed as planned, with no adverse cardiac events or deaths. However, the finding of silent coronary ischemia identified patients who were at high risk for future cardiac events, particularly those with left main ischemia (8%) and multivessel ischemia (40%). This prompted multidisciplinary patient management with BMT and Heart Team guidance on the need for and timing of elective coronary revascularization. The strategy of proactive treatment of silent coronary ischemia was shown to improve 1-year outcomes of patients with PAD following LER compared to historic controls.18 Systematic cardiac evaluation of patients with CLTI and no known CAD using coronary CTA + FFRCT at other centers have found similarly high rates of silent coronary ischemia (71%) (Figure 3).19

Ischemia-Targeted Coronary Revascularization vs Usual Care

To evaluate the clinical benefit of selective coronary revascularization in patients with CLTI and silent coronary ischemia, a single-center prospective study was conducted in 231 patients with no known CAD admitted to the hospital and cleared for elective LER. Patients with (a) systematic preoperative cardiac evaluation using coronary CTA + FFRCT with selective postop coronary revascularization (n = 111) were compared to (b) concurrent matched controls receiving Usual Care (n = 120) as recommended by guidelines with no preoperative coronary testing and no coronary revascularization. Limb-salvage surgery was successfully performed in all patients in both groups with no perioperative (30-day) mortality. In the CTA + FFRCT group, 58% had severe, silent coronary ischemia (FFRCT < 0.75), and elective ischemia-targeted coronary revascularization was performed in 42% of patients. No patients in the Usual Care group had elective coronary revascularization.

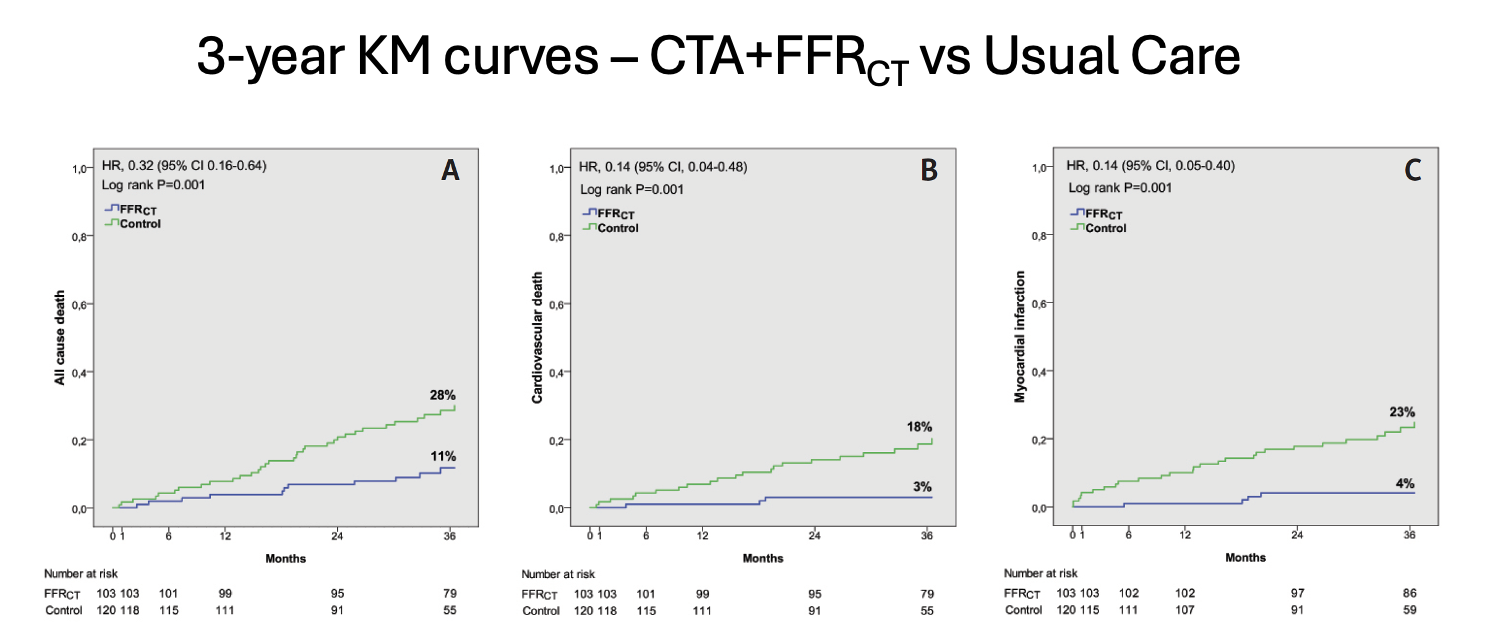

At 2-year follow-up, compared to Usual Care, the FFRCT group had fewer major adverse cardiovascular events (11% vs 23%, P = .02), fewer Mis (6% vs 18%, P = .01), and fewer cardiovascular deaths (5% vs 13%, P = .03).20

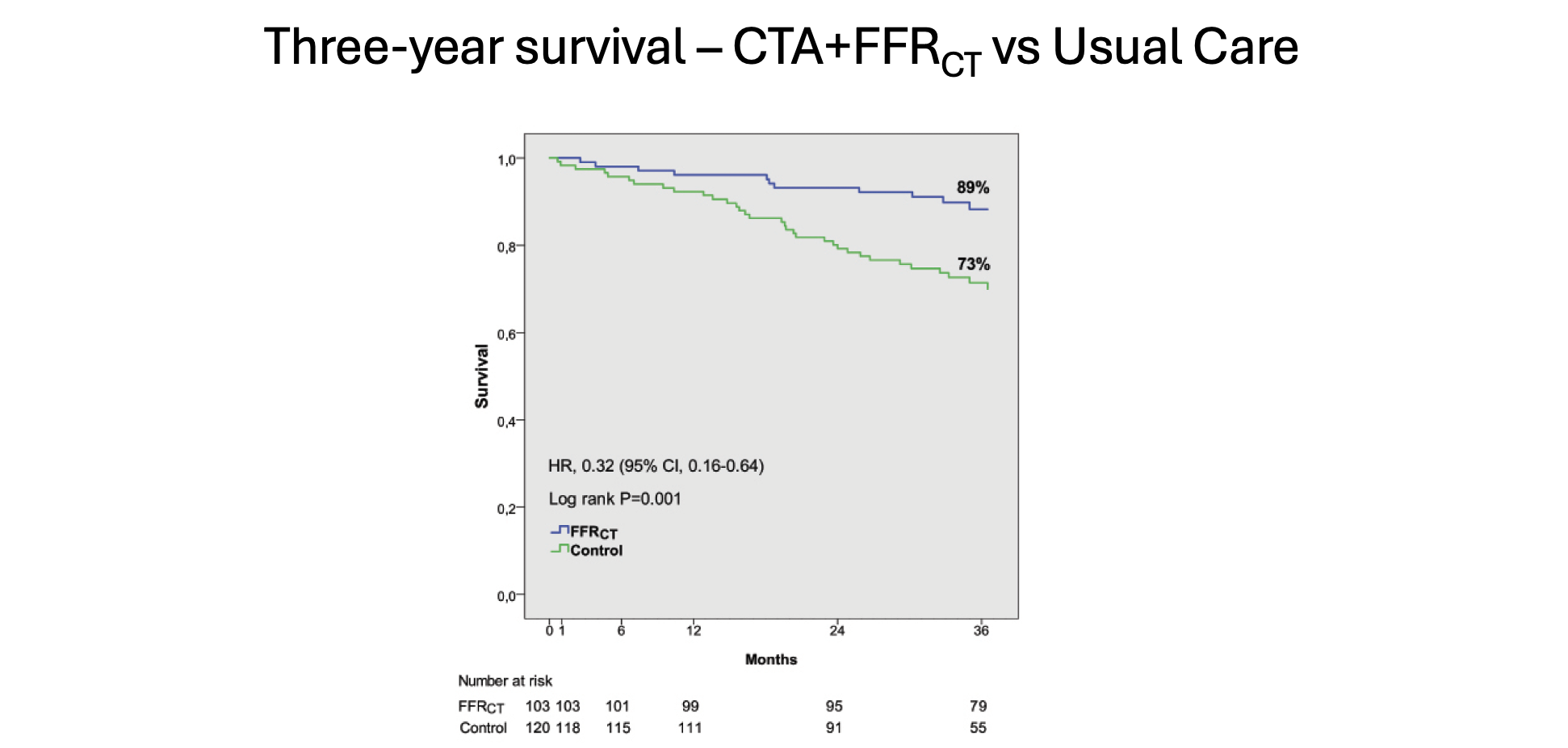

At 3 years in the FFRCT group, there was a twofold reduction in all-cause death (11% vs 28%, P <.001), primarily due to a sixfold reduction in cardiovascular death (3% vs 18%, P < .001) and a sixfold reduction in MI (4% vs 23%, P < .001) (Figure 4). Survival at 3 years was 89% in the FFRCT group compared to 73% in the Usual Care group (P < .001) (Figure 5).21

Long-term follow-up at 5 years showed a continuing benefit of coronary revascularization, with more than 50% reduction in all-cause death compared to patients receiving Usual Care (24% vs 47%, P < .001). This was associated with a fivefold reduction in cardiac death (5% vs 26%, P < .001) and a fourfold reduction in MI (7% vs 28%, P < .001). Five-year survival of patients with CLTI and CTA + FFRCT guided care was 76% compared to 53% for patients receiving guideline-directed Usual Care (P < .001).22

Can We Do Better With Selective Coronary Revascularization?

The results provided by the above-mentioned study suggests that we can do better with selective coronary revascularization. This study is the first evidence that diagnosis of silent coronary ischemia together with selective ischemia-guided coronary revascularization can reduce cardiac events and significantly improve long-term survival of patients with CLTI. However, it is important to note that this was a nonrandomized observational study with the potential for selection bias. Results from single-center studies cannot be generalized, and prospective, multicenter, randomized trial evidence are needed to validate these findings. One such randomized trial is currently underway.

Multicenter Randomized SCOREPAD Trial

The Selective COronary REvascularization in PAD patients after lower-extremity revascularization (SCOREPAD) trial (NCT 06250790) is aimed at addressing the problem of high mortality following LER.23 This prospective, international, multicenter randomized trial will enroll up to 600 patients with CLTI or severe limiting claudication and no known CAD (no prior MI, no coronary angiography or coronary revascularization, and no cardiac symptoms) after successful lower extremity revascularization. Patients will be randomized to (a) coronary CTA + FFRCT evaluation with ischemia-guided coronary revascularization, in addition to BMT or (b) Usual Care with BMT alone and no coronary revascularization. The primary endpoint at 2 years will be cardiac death, MI, or unplanned coronary revascularization, with extended follow-up to 5 years. Patient enrollment is currently underway; for further information, contact dainis.krievins@stradini.lv

Conclusions

More than 50% of patients with CLTI and no known CAD die within 5 years following successful LER. The primary cause of death is coexisting CAD, which is often asymptomatic, undiagnosed, and untreated. Current guideline-directed management of cardiac risk relies solely on evidence-based medical therapy and risk factor control, and this has been ineffective in reducing the alarmingly high mortality of patients with CLTI. A new strategy based on identifying patients with silent coronary ischemia using coronary CT-derived FFR together with proactive ischemia-targeted coronary revascularization shows promise in reducing adverse cardiac events and improving long-term survival following LER for CLTI. Further evidence from multicenter controlled and randomized trials is needed to define the role of coronary CTA + FFR-CT in the management of CAD in patients with CLTI. n

Affiliations and Disclosures

Christopher K. Zarins, MD, is Chidester Professor of Surgery, Emeritus, at Stanford University in Stanford, California, and Founder and Sr. Advisor for Clinical Science at HeartFlow, Inc., in Mountain View, California.

Dainis Krievins, MD, is Professor of Vascular Surgery at the University of Latvia and Director, Institute of Science, at Stradiņš University Hospital, both in Riga, Latvia.

Christopher K. Zarins, MD, has a financial interest In HeartFlow, Inc. Dainis Krievins, MD, reports no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Manuscript accepted October 20, 2025.

Address for correspondence: Christopher K. Zarins, MD, HeartfFlow, Inc., 331 E. Evelyn Ave., Mountain View, CA 94041. Email: zarins@heartflow.com

References

1. Conte MS, Bradbury A, Kolh P, et al; GVG Writing Group for the Joint Guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS), European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS), and World Federation of Vascular Societies (WFVS). Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019;58(1S): S1-S109.e33. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.05.006

2. Farber A, Menard MT, Conte MS, et al; BEST-CLI Investigators. Surgery or endovascular therapy for chronic limb-threatening ischemia. N Engl J Med. 2020;387(25):2305-2316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2207899

3. Bradbury AW, Moakes CA, Popplewell M, et al; BASIL-2 Investigators. A vein bypass first versus a best endovascular treatment first revascularization strategy for patients with chronic limb threatening ischaemia who require an infra-popliteal, with or without an additional more proximal infra-inguinal revascularization procedure to restore limb perfusion (BASIL-2): an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10390):1798-1809. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00462-2

4. Bager LGV, Petersen JK, Havers-Borgersen E, et al. The use of evidence-based medical therapy in patients with critical limb-threatening ischemia. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023;30(11):1092-1100. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwad022

5. Mustapha JA, Katzen BT, Neville RF, et al. Disease burden and clinical outcomes following initial diagnosis of critical limb ischemia in the Medicare population. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(10):1011-1012. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.12.012

6. Levin SR, Farber A, Goodney PP, et al; VQI-VISION. Five year survival in Medicare patients undergoing interventions for peripheral arterial disease: a retrospective cohort analysis of linked registry claims data. Eur J Vasc Enodvasc Surg. 2023;66(4):541-549. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2023.07.055

7. Mensah GA, Wei GS, Sorlie PD, et al. Decline in cardiovascular mortality: possible causes and implications. Circ Res. 2017;120(2):366-380. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309115

8. Hertzer NR, Beven EG, Young JR, et al. Coronary artery disease in peripheral vascular patients. A classification of 1000 coronary angiograms and results of surgical management. Ann Surg. 1984;199(2):223-233. doi:10.1097/00000658-198402000-00016

9. McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary-artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2795-2804. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041905

10. Aboyans V, Ricco J, Bartelink MEL, et al. Editor’s Choice - 2017 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55(3):305-368. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.07.018

11. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(3):e18-e114. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001038

12. Nørgaard BL, Terkelsen CJ, Mathiassen ON, et al. Coronary CT angiographic and flow reserve-guided management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(18):2123-2134. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.043

13. Navarese EP, Lansky AJ, Kereiakes DJ, et al. Cardiac mortality in patients randomised to elective coronary revascularization plus medical therapy or medical therapy alone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(45):4638-46 doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab24651

14. Ultee KHJ, Steunenberg SL, Schouten O. Rivaroxaban in peripheral artery disease after revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(21):2089-2090. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2030413

15. Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al; Writing Committee Members. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(22):e187- e285. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.053.e285

16. Conti CR, Bavry AA, Petersen JW. Silent ischemia: clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(5):435-441. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.050

17. Krievins D, Zellans E, Erglis A, Zvaigzne L, Lacis A, Jegere S et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic ischemia-producing coronary stenosis in patients with critical limb ischemia. Vascular Disease Management .2018;15(9):E96-E101.

18. Krievins D, Zellans E, Latkovskis G, et al. Pre-operative diagnosis of silent coronary ischemia may reduce post-operative death and myocardial infarction and improve survival of patients undergoing lower-extremity surgical revascularization. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;60(3):411-420. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2020.05.027

19. Stanley GA, Scherer MD, Hajostek M, et al. Utilization of coronary computed tomography angiography and computed tomography-derived fractional flow reserve in a critical limb-threatening ischemia cohort. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2024;10(2):101272. doi:10.1016/j.jvscit.2023.101272\

20. Krievins D, Zellans E, Latkovskis G, et al. Diagnosis of silent coronary ischemia with selective coronary revascularization may improve 2-year survival of patients with critical limb threatening ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2021;74(4):1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2021.03.059

21. Zellans E, Latkovskis G, Zarins CK, et al. Three-year survival of critical limb-threatening ischemia patients with FFRCT-guided coronary revascularization following lower-extremity revascularization. J Crit Limb Ischem. 2021;1(4):E140-E147.

22. Latkovskis G, Krievins D, Zellans E, et al. Ischemia-guided coronary revascularization following lower-extremity revascularization improves 5-year survival of patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J Endovasc Ther. 2024;15266028241245909. doi:10.1177/15266028241245909

23. Krievins D, Erglis A, Zarins CK. Addressing the need to improve long term survival following lower extremity revascularization in a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2024;68(4):541-542. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2024.06.015