Nerandomilast in Fibrotic Lung Diseases: A Clinical Evidence and Market Access Series

Part 3: Access Challenges and the Potential of Nerandomilast

Part 3: Access Challenges and the Potential of Nerandomilast

Click here to download the PDF version of this article.

Executive Summary

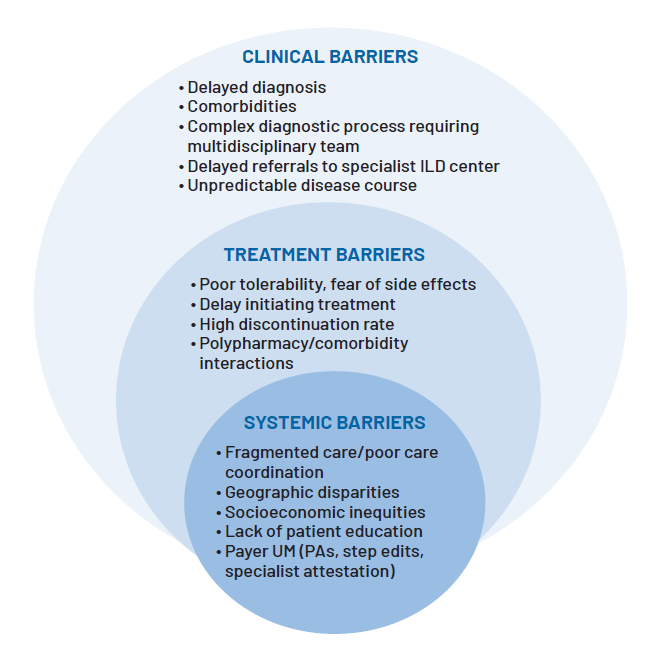

Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF), are devastating conditions marked by diagnostic delays, rapid progression, and premature mortality. Despite advances with antifibrotic therapies, patients continue to face systemic barriers across the care continuum: protracted time to diagnosis, fragmented care, geographic and socioeconomic disparities, payer utilization hurdles, and poor treatment tolerability. On average, patients wait 2.7 years for an accurate diagnosis, and about half are hospitalized at least twice before identification. These delays and systemic inequities translate into high costs, with patients incurring annual direct medical expenses of $20,000 to $30,000, on average, primarily driven by hospitalizations.

The current standard of care, which includes antifibrotics, oxygen supplementation, and palliative therapy, slows but does not reverse disease progression. Although clinically valuable, antifibrotic

therapies convey costs of approximately $9,000 per month in the United States; however, discontinuation due to tolerability issues undermines patient outcomes and erodes payer value by generating spend without sustained clinical benefit. Patients report high levels of anxiety and inadequate support, while rural and disadvantaged populations remain disproportionately affected.

As a result, adherence and persistence remain limited, and health care utilization continues to escalate, yielding suboptimal return on therapeutic investment. Cumulative annual costs—including antifibrotics, hospitalizations, oxygen therapy, and follow-up testing—can exceed $130,000 for a typical patient.

Nerandomilast, an investigational oral, selective phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) inhibitor now in late-phase clinical development, has demonstrated promising efficacy in both IPF and PPF, with an improved tolerability profile that may support better adherence. If confirmed and approved, it could represent a meaningful addition to the ILD treatment landscape, broadening therapeutic options and potentially reducing discontinuation rates, improving persistence, and potentially lowering total care costs linked to hospitalizations, side effect management, and treatment inefficiencies.

Realizing the full benefits of innovation will require proactive payer engagement, evidence generation, and equitable access strategies. Stakeholders can improve patient outcomes by addressing persistent barriers while optimizing health care resources. In fibrosing ILDs, where treatment delay translates to irreversible loss of lung function, closing access gaps is both a clinical imperative and an economic necessity.

Introduction

Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF), represent a devastating cluster of conditions marked by severe clinical trajectories and significant system-level challenges.1,2 Over the past decade, therapeutic advances have expanded treatment options. Yet patients still encounter major barriers to timely diagnosis, effective therapy, sustained access to care, and substantial health care utilization.3,4 These challenges are compounded by the unpredictable, variable nature of disease progression and the complexity of managing comorbidities in an older population, with the disease typically presenting in the sixth or seventh decade of life.5

This white paper examines the multifaceted barriers that limit access to optimal care for patients with fibrosing ILDs, focusing on IPF and PPF. It explores payer, provider, and patient perspectives, highlighting how novel therapies in development, including nerandomilast, an investigational agent with a unique mechanism, may help address persistent access gaps if approved by regulatory authorities. The goal is to provide a clear view of the challenges and potential strategies to improve patient outcomes through evidence-based access decisions.

Fibrosing ILDs: A Growing and Devastating Burden

Fibrosing ILDs are progressive, scarring diseases of the lung parenchyma that impair gas exchange and lead to inexorable respiratory decline.5 IPF, the prototypical fibrosing ILD, has an adjusted prevalence of 2.40 to 2.98 cases per 10,000 individuals in North America, with both incidence and prevalence rising. Once categorized as a rare disease, IPF may no longer meet that designation.6 Mortality is sobering—median survival is only three to five years from diagnosis, comparable to many aggressive cancers.7

Recognition of PPF as a distinct form of fibrotic disease outside of IPF has expanded awareness of fibrosing ILDs. Patients with fibrosing ILDs such as chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, interstitial pneumonia, connective tissue disease–associated ILD, and unclassifiable ILD are at risk of developing a progressive fibrosing phenotype. An estimated 13% to 40% of these non-IPF fibrosing ILDs progress within two years despite appropriate management, with clinical trajectories, including rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) and transplant-free survival, closely resembling those seen in IPF.8 Collectively, fibrosing ILDs exert substantial human and economic costs. Patients experience severe dyspnea, worsening cough, functional limitations, and deterioration of quality of life. At the same time, health care systems absorb costs from frequent hospitalizations due to acute exacerbations, oxygen therapy, and end-of-life care.1

Recognition of PPF as a distinct form of fibrotic disease outside of IPF has expanded awareness of fibrosing ILDs. Patients with fibrosing ILDs such as chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, interstitial pneumonia, connective tissue disease–associated ILD, and unclassifiable ILD are at risk of developing a progressive fibrosing phenotype. An estimated 13% to 40% of these non-IPF fibrosing ILDs progress within two years despite appropriate management, with clinical trajectories, including rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) and transplant-free survival, closely resembling those seen in IPF.8 Collectively, fibrosing ILDs exert substantial human and economic costs. Patients experience severe dyspnea, worsening cough, functional limitations, and deterioration of quality of life. At the same time, health care systems absorb costs from frequent hospitalizations due to acute exacerbations, oxygen therapy, and end-of-life care.1

Current Treatments: Incremental Progress but Persistent Gaps

Until 2014, treatment options for IPF were limited and largely ineffective, relying on immunosuppressant therapy with little evidence of benefit, supplemental oxygen, and supportive care. In 2014, findings from the PANTHER-IPF trial demonstrated that triple therapy with prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine—then considered the standard of care for IPF—was associated with higher risks of hospitalization and mortality.5

A transformative shift occurred in 2014, when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pirfenidone and nintedanib, the first antifibrotic therapies demonstrated to slow the decline in lung function. Nintedanib was later approved for other chronic ILDs with a progressive phenotype and for systemic sclerosis–associated ILD, further expanding therapeutic options.9,10

While these therapies represent meaningful progress, they fail to address the full disease burden. Antifibrotics do not reverse established fibrosis or halt progression entirely, nor do they significantly improve clinical symptoms—their role appears to be in slowing decline, buying patients valuable time.5 Yet, tolerability remains a major barrier. Both pirfenidone and nintedanib are associated with significant gastrointestinal side effects, including nausea and diarrhea, as well as elevations in liver enzymes, all of which frequently lead to dose reductions or discontinuation.5 For many patients or providers, the fear of side effects may contribute to delayed treatment initiation or poor adherence.11

A retrospective cohort analysis determined the total paid amount for IPF patients on pirfenidone averaged $8,889.49 per month, with $394.49 out of pocket. In contrast, patients on nintedanib averaged $9,367.91 monthly, with $397.51 out of pocket. Overall, both therapies cost more than $106,000 per year. Yet, nearly 43% of treated patients discontinued their medication during the study period, with an average treatment duration of only 10 months.12

A retrospective cohort analysis determined the total paid amount for IPF patients on pirfenidone averaged $8,889.49 per month, with $394.49 out of pocket. In contrast, patients on nintedanib averaged $9,367.91 monthly, with $397.51 out of pocket. Overall, both therapies cost more than $106,000 per year. Yet, nearly 43% of treated patients discontinued their medication during the study period, with an average treatment duration of only 10 months.12

Prescription costs are in addition to several other expenses faced by patients with IPF, who often have multiple comorbidities requiring additional medications, frequent oxygen supplementation, hospitalizations, office visits, imaging, and lab testing. According to a Markov model–based analysis, annual follow-up costs alone—including oxygen therapy ($8,916), office visits ($890), pulmonary function tests ($680), echocardiograms ($401), computed tomography (CT) scans ($241), palliative care ($160), pulmonary rehabilitation ($62), and six-minute walk tests ($51)—total approximately $12,291 per patient.13

Polypharmacy further complicates management. Patients with fibrosing ILDs are often older and have multiple comorbidities such as hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).14 Drug-drug interactions and competing medication burdens can potentially exacerbate tolerability issues and fragment adherence. As a result, patients might struggle to achieve sustained benefit from antifibrotic therapy, leaving a pressing unmet need for treatments with improved tolerability, simplified administration, and differentiated mechanisms of action.

The Diagnosis Dilemma: Lost Time, Lost Opportunity

One of the greatest barriers to effective ILD care is delayed diagnosis. A retrospective analysis of Medicare fee-for-service claims data (2014-2019) found that, on average, patients received an IPF diagnosis 2.7 years after their first recorded respiratory-related diagnosis. About half of the patients experienced two or more hospitalizations for respiratory issues before IPF was formally identified.15 The delay is mainly attributable to nonspecific symptoms and overlapping comorbidities, with features such as cough and dyspnea frequently misattributed to asthma, COPD, or heart failure. The inherent complexity of the diagnostic process, including the requirement for multidisciplinary discussion, adds to these delays. Moreover, limited recognition of IPF in general practice often postpones referral to specialized ILD centers, where timely diagnosis, expert management, and access to supportive resources can be achieved.16

Each month lost to diagnostic delay represents irreversible progression of lung fibrosis. A prolonged delay in diagnosis is linked to diminished quality of life, which, in turn, is associated with declining lung function, the emergence of comorbidities, and overall disease progression, often culminating in emergency events, hospitalizations, and increased mortality. By the time patients are diagnosed, many may have already lost substantial lung function, limiting the potential benefit of therapy.16

Each month lost to diagnostic delay represents irreversible progression of lung fibrosis. A prolonged delay in diagnosis is linked to diminished quality of life, which, in turn, is associated with declining lung function, the emergence of comorbidities, and overall disease progression, often culminating in emergency events, hospitalizations, and increased mortality. By the time patients are diagnosed, many may have already lost substantial lung function, limiting the potential benefit of therapy.16

A systematic review of 25 cost studies and seven cost-effectiveness analyses found that annual direct medical costs ranged from $1,824 to $116,927 per ILD patient (median $32,834), driven primarily by inpatient care (55%), followed by outpatient visits (22%) and medications (18%). In contrast, indirect costs for employed patients ranged from $7,149 to $10,902 per year (median $9,607). Of the cost-effectiveness analyses, only one study showed that a therapy (ambulatory oxygen) was cost-effective versus best supportive care.17

For IPF specifically, a systematic literature review of 88 studies estimated annual per-patient costs at approximately $20,000, 2.5-3.5 times higher than national health care expenditure, with matched control comparisons consistently showing excess utilization and costs.18

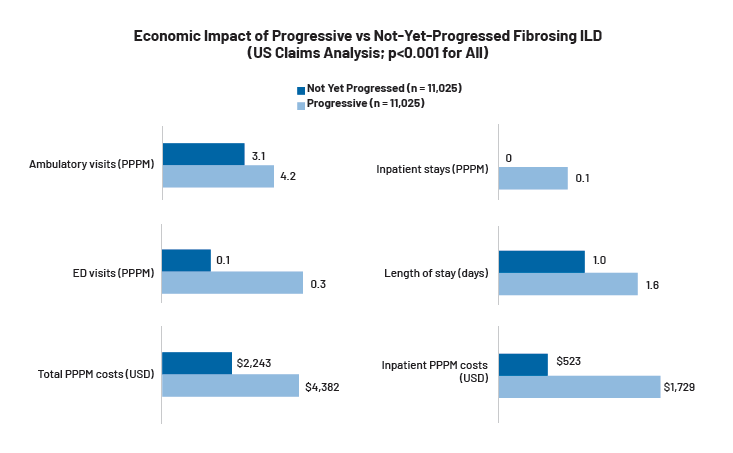

As ILD advances, patients require more frequent outpatient and emergency visits, hospitalizations, and long-term interventions, translating into higher health care utilization and costs. A retrospective study of 22,050 insured US adults newly diagnosed with non-IPF fibrosing ILD—conducted using administrative claims data from the Optum Research Database—found that progressive disease was associated with significantly higher health care utilization and costs when compared to patients with ILDs who had not yet progressed. Progressive patients had more ambulatory visits (4.2 vs 3.1 per patient per month [PPPM]), emergency department (ED) visits (0.3 vs 0.1 PPPM), and inpatient stays (0.1 vs 0.0 PPPM) with longer admissions (1.6 vs 1.0 days). Total PPPM costs were nearly double ($4,382 vs $2,243) for progressive patients, driven primarily by higher inpatient costs ($1,729 vs $523 PPPM), highlighting the economic impact of disease progression and the potential value of interventions that can help reduce hospitalizations.19

The Unpredictable Course of ILDs: A Challenge for Patients and Payers

Even once diagnosed, ILDs present a uniquely unpredictable disease course. Some patients experience a slow, steady decline, while others suffer a rapid progression punctuated by acute exacerbations that resemble respiratory crises.5 Predicting individual trajectories is nearly impossible,1 complicating both clinical decision-making and payer forecasting of disease burden.

Even once diagnosed, ILDs present a uniquely unpredictable disease course. Some patients experience a slow, steady decline, while others suffer a rapid progression punctuated by acute exacerbations that resemble respiratory crises.5 Predicting individual trajectories is nearly impossible,1 complicating both clinical decision-making and payer forecasting of disease burden.

For patients, this uncertainty fuels anxiety and complicates life planning. Consulting multiple physicians and receiving conflicting information—combined with limited psychological support, scarce educational resources, and difficult decisions such as whether to pursue lung transplantation—all contribute to heightened anxiety. Surveys indicate patients frequently lack clear guidance on the disease, treatment options, and supportive care at the time of diagnosis.20

Online surveys from patients and pulmonologists in Europe and Canada, for example, found that 40% of surveyed patients did not feel that they received enough information from their physicians at diagnosis, with just 42% reporting that they were offered pharmacological treatment at the same

time as receiving their diagnosis, and only 10% initiating treatment when it was first presented.21

For payers and providers, the unpredictable disease course challenges the allocation of resources. It raises questions about when to escalate care or initiate costly therapies, underscoring the importance of early intervention and continuous monitoring.

Beyond Diagnosis: Fragmented Care

ILD management requires multidisciplinary expertise spanning pulmonology, radiology, and pathology, with guidelines set by the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) committee recommending the use of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) as a gold standard for diagnosing patients with IPF.22 Yet, care is often fragmented, and running MDTs in practice may be burdensome and time-consuming, with patients frequently moving between specialists without a coordinated or well-communicated treatment plan.22 Fragmentation may increase the risk of duplicative testing, inconsistent recommendations, and delayed treatment initiation.

For payers, fragmented care drives inefficiency, unnecessary utilization, and inconsistent outcomes. Integrated, coordinated care models remain underdeveloped in ILD management, leaving patients and health systems vulnerable to avoidable complications.

Socioeconomic Barriers and Geographic Disparities

Access to ILD care is not evenly distributed. Geographic disparities mean that patients living in rural areas, without access to academic or ILD specialty  centers, face substantial travel burdens, often leading to delayed or foregone care. Community providers may lack the expertise to recognize and manage the more than 200 distinct ILDs that require multidisciplinary care, vigilant monitoring, and timely diagnosis to optimize outcomes—and research has found that rural patients generally present to specialist care with worse disease severity compared to their suburban counterparts. Additionally, utilization of antifibrotics is often hindered by a lack of access to specialist centers, primarily due to geographic distances.23

centers, face substantial travel burdens, often leading to delayed or foregone care. Community providers may lack the expertise to recognize and manage the more than 200 distinct ILDs that require multidisciplinary care, vigilant monitoring, and timely diagnosis to optimize outcomes—and research has found that rural patients generally present to specialist care with worse disease severity compared to their suburban counterparts. Additionally, utilization of antifibrotics is often hindered by a lack of access to specialist centers, primarily due to geographic distances.23

While treatments and palliative care can delay progression and relieve symptoms, disparities in access, driven by race, gender, geography, and socioeconomic status, disproportionately affect disadvantaged populations.23

Studies show that patients with lower socioeconomic status were less likely to be on antifibrotic therapy when referred to an ILD treatment center. High out-of-pocket costs for antifibrotics, oxygen therapy, and supportive care can discourage adherence or push patients to ration treatment. In addition, patients with IPF residing in more affluent areas or possessing non-Medicaid insurance demonstrated a higher likelihood of receiving lung transplants and post-discharge rehabilitation, whereas those of lower socioeconomic status or with Medicaid or no insurance faced markedly reduced access to these interventions.23

For payers, these disparities highlight the need for equitable coverage strategies that reduce financial toxicity while ensuring access to high-value therapies.

Payer Utilization Management Strategies: Necessary Guardrails or Barriers to Care?

To manage costs, payers often use utilization management (UM) strategies such as prior authorization (PA), step therapy, and restrictive reauthorization criteria for antifibrotic coverage. While antifibrotics are generally covered on formulary, PA requirements typically confirm an IPF diagnosis, often with specialist attestation, recent pulmonary function test results (eg, FVC), and evidence from high-resolution CT (HRCT) or lung biopsy.

Although intended to ensure appropriate use, these processes frequently create friction that delays treatment initiation. PA reviews can take weeks, and step therapy may require patients to fail older, less effective regimens before accessing antifibrotics. For patients with fibrosing ILDs, these delays can have profound clinical consequences for a progressive, irreversible illness. For providers, administrative burden increases frustration, may weaken the therapeutic alliance between patients and clinicians, and may discourage guideline-concordant prescribing.24 In essence, UM strategies may risk short-term savings at the expense of long-term costs associated with accelerated disease progression and hospitalizations.

Nerandomilast: A Novel Mechanism in Development

Nerandomilast is an investigational oral phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) inhibitor designed to modulate key inflammatory and fibrotic pathways implicated in ILD progression. Unlike current antifibrotics like pirfenidone, which primarily target fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition, nerandomilast acts upstream by regulating pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling and fibroblas-timmune interactions.25,26

Early clinical studies suggest that nerandomilast may offer favorable tolerability and efficacy, preventing a decrease in lung function in patients with IPF over 12 weeks, regardless of whether patients received a background antifibrotic agent.27 Importantly, its selective PDE4B inhibition may mitigate some of the tolerability challenges seen with antifibrotics.26

Initial data from phase 3 confirmatory studies show that nerandomilast could meaningfully add to the ILD treatment landscape. Importantly, nerandomilast is being studied both as monotherapy and in conjunction with currently approved antifibrotics, reflecting an interest in whether additive or

Initial data from phase 3 confirmatory studies show that nerandomilast could meaningfully add to the ILD treatment landscape. Importantly, nerandomilast is being studied both as monotherapy and in conjunction with currently approved antifibrotics, reflecting an interest in whether additive or

synergistic effects could improve long-term patient outcomes.

In the FIBRONEER-IPF and FIBRONEER-ILD phase 3 confirmatory trials, nerandomilast demonstrated statistically significant reductions in the rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks compared with placebo across populations with IPF and PPF, respectively.28,29 These findings suggest a possible pan-ILD effect, positioning nerandomilast as the first therapy to show benefit in both IPF and PPF within large, randomized phase 3 trials.

Equally important, nerandomilast was generally well tolerated across both trials, with lower rates of treatment discontinuation compared with historical data from antifibrotics.28,29 The possibility of improved adherence and persistence, driven by a differentiated safety profile, may have significant

downstream implications for real-world effectiveness and health care resource utilization if future regulatory approvals are obtained.

Taken together, initial phase 3 data suggest that nerandomilast could represent a meaningful addition to the ILD treatment landscape, potentially expanding therapeutic options beyond the current standard of care.

However, as nerandomilast remains an investigational agent, further data and regulatory review will be required before its role in clinical practice is established. An ongoing open-label extension (OLE) trial, known as FIBRONEER-ON, is evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of nerandomilast (BI 1015550) in patients with IPF or PPF. This extension trial allows patients who completed the FIBRONEER-IPF and FIBRONEER-ILD trials to continue treatment with nerandomilast and aims to assess adverse events over the two-year study, along with long-term efficacy outcomes, including FVC change, and time to first exacerbation, disease progression, hospitalization, and death.30

Why Access Matters in Fibrosing ILDs: Outcomes Depend on Early and Sustained Care

When considered together, the barriers facing ILD patients form a complex ecosystem of unmet needs. Diagnostic delays, unequal access to specialists, high drug costs, payer restrictions, tolerability concerns, and geographic disparities all contribute to suboptimal outcomes. These challenges are interconnected—for example, delayed diagnosis leads to later initiation of costly therapy, while tolerability issues lead to discontinuation that undermines payer investment.

Understanding these interconnected barriers is critical. Each represents a point at which the value of therapy is eroded, either through underutilization, poor adherence, or inefficient resource allocation.

Timely initiation and consistent adherence to antifibrotic therapy can help slow lung function decline, reduce the risk of acute exacerbations, and improve outcomes.31 Yet, system-level barriers often erode these benefits. Without systemic interventions, patients continue to experience fragmented and inadequate care. And every month of delayed therapy may mean irreversible loss of lung capacity.

Timely initiation and consistent adherence to antifibrotic therapy can help slow lung function decline, reduce the risk of acute exacerbations, and improve outcomes.31 Yet, system-level barriers often erode these benefits. Without systemic interventions, patients continue to experience fragmented and inadequate care. And every month of delayed therapy may mean irreversible loss of lung capacity.

For payers, untreated or undertreated diseases may translate into higher downstream costs, including emergency visits, hospitalizations, and long-term supportive care. The challenge is to balance cost containment with timely access, ensuring that utilization strategies do not inadvertently accelerate disease burden or health care costs.

Nerandomilast’s Potential to Address Access Barriers

If ultimately approved, nerandomilast could play a meaningful role in addressing many of the barriers described above. While definitive evidence awaits phase 3 readouts and results from extension studies, early data and its pharmacologic profile suggest several potential advantages:28,29

- Tolerability: Selective PDE4B inhibition may improve gastrointestinal tolerability relative to broader PDE4 inhibition or existing antifibrotics, reducing discontinuation rates linked to side effects, or potentially supporting earlier intervention in patients who otherwise go untreated due to fear of side effects.

- Polypharmacy compatibility: A favorable tolerability profile could ease concerns for older patients managing comorbidities with multiple medications.

- Broader indication potential: Nerandomilast is being studied in IPF and non-IPF fibrosing ILDs, which could broaden eligibility and improve access for patients currently excluded from antifibrotic treatment.

- Equity of access: Improved tolerability and oral dosing could benefit patients in rural or underserved areas who face challenges accessing specialty centers for infusion or intensive monitoring.

- Economic potential: If nerandomilast is priced competitively, its oral, twice-daily regimen with good tolerability could reduce total care costs (eg, fewer doctors’ visits to monitor and treat side effects, fewer treatment dropouts, improved quality of life, reduced hospitalizations, delayed lung transplant).

For payers, nerandomilast’s potential to improve adherence and reduce discontinuation is critical. Poor persistence with antifibrotics erodes value, as payers incur costs without realizing full clinical benefit. A therapy that patients can tolerate and remain on may deliver greater value by maximizing outcomes per dollar spent.

Engaging Payers: Strategies for Evidence and Access

As new therapies for fibrosing ILDs approach potential market entry, stakeholders must engage payers early with robust and comprehensive evidence. Real-world evidence can play a critical role in this process by demonstrating the impact of treatment on adherence, persistence, and health care utilization outcomes in routine clinical practice. These data provide payers with insights into how therapies perform outside the controlled environment of clinical trials and help establish the practical value of treatment.

Health economic modeling will also be vital to quantify the costs associated with delayed diagnosis, treatment discontinuation, and hospitalizations, compared with the potential value of effective and sustained therapy. By framing the conversation around cost offsets and long-term outcomes, stakeholders can show how improved access translates into financial and clinical benefits.

Subgroup analyses can strengthen the evidence base by identifying populations most likely to benefit from treatment, supporting targeted coverage strategies that align with payer priorities. Collaborative initiatives with ILD specialty centers will be equally important, as these partnerships can promote timely diagnosis, enhance care coordination, and reduce inefficiencies in the patient journey.

Ultimately, payers will require compelling evidence of clinical efficacy and a clear demonstration of economic impact. Showing that improved tolerability and adherence can reduce hospitalizations, slow disease progression, and optimize health care resource utilization will be essential to securing broad, equitable coverage and ensuring that patients realize the full benefits of therapeutic innovation.

Looking Ahead: A Tipping Point for ILD Care

The field of fibrosing ILDs is at an inflection point. A decade ago, no approved antifibrotics existed. Today, multiple therapies are available, and new mechanisms are in development. Yet, persistent barriers continue to blunt the potential impact of innovation. As new agents like nerandomilast advance through clinical trials, payers and providers have an opportunity to reshape access strategies to ensure that patients derive maximum benefit.

The field of fibrosing ILDs is at an inflection point. A decade ago, no approved antifibrotics existed. Today, multiple therapies are available, and new mechanisms are in development. Yet, persistent barriers continue to blunt the potential impact of innovation. As new agents like nerandomilast advance through clinical trials, payers and providers have an opportunity to reshape access strategies to ensure that patients derive maximum benefit.

Nerandomilast, a selective PDE4B inhibitor in development, has the potential to address several of these barriers if future trials confirm efficacy and tolerability. For payers, clinicians, and decision-makers, preparing for this next generation of therapy requires scientific evaluation and thoughtful strategies to overcome systemic barriers to access. By addressing these challenges proactively, the health care community can help ensure that innovation translates into meaningful improvements in patient care. Improving access is clinically necessary and economically prudent in fibrosing ILDs, where time lost equals lung lost.

References:

- Kolb M, Vašáková M. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):57. doi:10.1186/s12931-019-1022-1

- Wuyts WA, Papiris S, Manali E, et al. The burden of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: a DELPHI approach. Adv Ther. 2020;37(7):3246-3264. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01384-0

- Cosgrove GP, Bianchi P, Danese S, Lederer DJ. Barriers to timely diagnosis of interstitial lung disease in the real world: the INTENSITY survey. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12890-017-0560-x

- Bramhill C, Langan D, Mulryan H, Eustace-Cook J, Russell AM, Brady AM. A scoping review of the unmet needs of patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). PLoS One. 2024;19(2):e0297832. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0297832

- Pleasants R, Tighe RM. Management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(12):1238-1248. doi: 10.1177/1060028019862497

- Pergolizzi JV Jr, LeQuang JA, Varrassi M, Breve F, Magnusson P, Varrassi G. What do we need to know about rising rates of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? A narrative review and update. Adv Ther. 2023;40(4):1334-1346. doi:10.1007/s12325-022-02395-9

- Tomassetti S, Ravaglia C, Piciucchi S, et al. Historical eye on IPF: a cohort study redefining the mortality scenario. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1151922. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1151922

- Kang HK, Song JW. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis: where are we now? Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2024;87(2):123-133. doi:10.4046/trd.2023.0119

- Boehringer Ingelheim. FDA approves Ofev® as the first and only therapy to slow the rate of decline in pulmonary function in patients with systemic sclerosisassociated ILD [Press Release]. Boehringer Ingelheim. September 6, 2019. Accessed August 28, 2025. https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/us/media/press-releases/fda-approves-ofev-first-and-only-therapy-slow-rate-declinepulmonary-function-patients-systemic

- Boehringer Ingelheim. FDA approves Ofev® as first treatment for chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype [Press Release]. Boehringer Ingelheim. March 9, 2020. Accessed August 28, 2025. https://www.boehringeringelheim.com/us/media/press-releases/fda-approves-ofev-first-treatmentchronic-fibrosing-ilds-progressive-phenotype

- Lee CT, Hao W, Burg CA, Best J, Kolenic GE, Strek ME. The impact of antifibrotic use on long-term clinical outcomes in the pulmonary fibrosis foundation registry. Respir Res. 2024;25(1):255. doi:10.1186/s12931-024-02883-2

- Dempsey TM, Payne S, Sangaralingham L, Yao X, Shah ND, Limper AH. Adoption of the antifibrotic medications pirfenidone and nintedanib for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(7):1121-1128. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202007-901OC

- Dempsey TM, Thao V, Moriarty JP, Borah BJ, Limper AH. Cost-effectiveness of the anti-fibrotics for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):18. doi:10.1186/s12890-021-01811-0

- Glassberg MK. Overview of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, evidence-based guidelines, and recent developments in the treatment landscape. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(11 Suppl):S195-S203. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31419091/

- Herberts MB, Teague TT, Thao V. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States: time to diagnosis and treatment. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):281. doi:10.1186/s12890-023-02565-7

- Wang X, Xia X, Hou Y et al. Diagnosis of early idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current status and future perspective. Respir Res. 2025;26(1):192. doi:10.1186/s12931-025-03270-1

- Wong AW, Koo J, Ryerson CJ, Sadatsafavi M, Chen W. A systematic review on the economic burden of interstitial lung disease and the cost- effectiveness of current therapies. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):148. doi:10.1186/s12890-022-01922-2

- Diamantopoulos A, Wright E, Vlahopoulou K, Cornic L, Schoof N, Maher TM. The burden of illness of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a comprehensive evidence review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(7):779-807. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0631-8

- Singer D, Bengtson LGS, Conoscenti CS, et al. Burden of illness in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(8):871-880. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.8.871

- Wuyts WA, Peccatori FA, Russell AM. Patient-centred management in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: similar themes in three communication models. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(132):231-238. doi:10.1183/09059180.00001614

- Maher TM, Swigris JJ, Kreuter M, et al. Identifying barriers to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treatment: a survey of patient and physician views. Respiration. 2018;96(6):514-524. doi: 10.1159/000490667

- Cottin V, Martinez FJ, Smith V, Walsh SLF. Multidisciplinary teams in the clinical care of fibrotic interstitial lung disease: current perspectives. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(165):220003. doi:10.1183/16000617.0003-2022

- Tikellis G, Holland AE. Health disparities and associated social determinants of health in interstitial lung disease: a narrative review. Eur Respir Rev. 2025;34(176):240176. doi:10.1183/16000617.0176-2024

- Anderson KE, Darden M, Jain A. Improving prior authorization in Medicare Advantage. JAMA. 2022;328(15):1497-1498. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.17732

- Bonella F, Spagnolo P, Ryerson C. Current and future treatment landscape for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Drugs. 2023;83(17):1581-1593. doi: 10.1007/s40265-023-01950-0

- Aringer M, Distler O, Hoffmann-Vold AM, Kuwana M, Prosch H, Volkmann ER. Rationale for phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition as a treatment strategy for interstitial lung diseases associated with rheumatic diseases. RMD Open. 2024;10(4):e004704. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2024-004704

- Richeldi L, Azuma A, Cottin V, et al. Trial of a preferential phosphodiesterase 4B inhibitor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(23):2178-2187. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2201737

- Maher TM, Assassi S, Azuma A, et al. Nerandomilast in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(22):2203-2214. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2503643

- Richeldi L, Azuma A, Cottin V, et al. Nerandomilast in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(22):2193-2202. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2414108

- Wuyts WA, Richeldi L, Assassi S, et al. Design of the FIBRONEER-ON openlabel extension trial of nerandomilast (BI 1015550) [Abstract]. Eur Respir J.2024;64(suppl 68):PA672. doi:10.1183/13993003.congress-2024.PA672

- Maher TM, Strek ME. Antifibrotic therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: time to treat. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):205. doi:10.1186/s12931-019-1161-4

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of First Report Managed Care or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.