Nerandomilast in Fibrotic Lung Diseases: A Clinical Evidence and Market Access Series

Part 2: Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis Phase 3 Trial Results

Part 2: Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis Phase 3 Trial Results

Click here to download the PDF version of this article.

Executive Summary

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) are high-burden diseases with limited treatment options.

- This paper focuses on nerandomilast, a selective phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) inhibitor with antifibrotic and immunomodulatory effects.

- In a Phase 3 trial, nerandomilast showed statistically significant preservation of lung function in patients with PPF, both with and without background antifibrotic therapy.

- Nerandomilast demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with low rates of treatment discontinuation and no increase in PDE4-associated adverse events versus placebo.

- Mortality was substantially lower in the nerandomilast treatment groups versus placebo, indicating a potential survival benefit.

- Together, these data suggest nerandomilast has the potential to transform treatment paradigms in PPF as a monotherapy and add-on treatment.

Introduction

Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases: Separate But Overlapping Entities

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) encompass a diverse range of pulmonary conditions with different, and often indeterminant, etiologies, many of which result in fibrotic remodeling of the lung. Among these, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the archetypal progressive fibrotic ILD, marked by irreversible scarring of lung parenchyma, progressive respiratory decline, and premature mortality despite treatment.1,2 The therapeutic landscape for IPF has evolved with the introduction of antifibrotic agents, yet these agents offer only incremental survival benefits, and they fall short of altering the fundamental trajectory of the disease, with patients still experiencing relentless disease progression.3,4

Progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF)—as defined by the 2022 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/Japanese Respiratory Society/Asociación Latinoamericana de Tórax (ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT) Clinical Practice guidelines—encompasses a broader spectrum of non-IPF fibrotic ILDs that share similar patterns of disease progression, symptom burden, and functional decline and involve progression beyond the interstitial space into the broader lung parenchyma.5 These include fibrotic connective tissue disease-related ILD, fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonia, pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis, and unclassified fibrotic ILDs, among others.5

Progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF)—as defined by the 2022 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/Japanese Respiratory Society/Asociación Latinoamericana de Tórax (ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT) Clinical Practice guidelines—encompasses a broader spectrum of non-IPF fibrotic ILDs that share similar patterns of disease progression, symptom burden, and functional decline and involve progression beyond the interstitial space into the broader lung parenchyma.5 These include fibrotic connective tissue disease-related ILD, fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonia, pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis, and unclassified fibrotic ILDs, among others.5

Despite differences in etiology, PPF follows a clinical course that mirrors IPF and carries a similarly poor prognosis once progression begins. Critically, current treatment strategies for PPF are often extrapolated from IPF data and offer limited benefit in halting disease progression or extending survival. No therapies are specifically approved for PPF in most markets, with treatment decisions often guided by individualized clinical judgment in the absence of definitive guidance for non-IPF progressive ILDs.6

As such, PPF represents a major therapeutic gap, characterized not by lack of recognition but by a lack of effective, targeted interventions. The need for new, well-tolerated agents that address the fibrotic cascade across ILD subtypes remains urgent and unmet.6

The ILD Treatment Landscape

The treatment landscape for ILD has not seen new antifibrotic options enter the armamentarium since 2014, when the first-generation antifibrotics pirfenidone and nintedanib were both approved.7,8 The tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), nintedanib, targets multiple receptors involved in fibrogenesis to inhibit fibroblast proliferation, migration, and differentiation.9 Pirfenidone exerts its antifibrotic effects through different mechanisms that include antioxidative effects, downregulation of transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1), and inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine activity.9 Nintedanib is approved in the US to treat IPF and other chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype and systemic sclerosis-associated ILD.8 Pirfenidone has only received US approval to treat IPF.7

Nintedanib and pirfenidone modestly slow the annual rate of forced vital capacity (FVC) decline in IPF but do not substantially alter the underlying disease processes or improve survival to a meaningful extent.9 In fact, several studies show an increased risk of hospitalization in patients treated with antifibrotics even though they had less severe baseline symptoms, but this may have been an unintended byproduct of confounding variables such as more prolonged survival in treated patients.10 While direct comparisons of antifibrotics in IPF and PPF are sparse, emerging data suggest that the benefits of antifibrotics may be smaller in PPF than in IPF. In a study of real-world patients, antifibrotic therapy preserved 562 mL of FVC at 96 months in IPF (−1131.34 mL with antifibrotics vs −1692.8 mL without) and 654 mL in non-IPF PPF (−533.90 mL vs −1187.9 mL). Despite this numerically greater FVC preservation in PPF, overall survival was significantly prolonged only in IPF (P=0.001), with no survival benefit observed in PPF (P=0.3263).11

Nintedanib and pirfenidone modestly slow the annual rate of forced vital capacity (FVC) decline in IPF but do not substantially alter the underlying disease processes or improve survival to a meaningful extent.9 In fact, several studies show an increased risk of hospitalization in patients treated with antifibrotics even though they had less severe baseline symptoms, but this may have been an unintended byproduct of confounding variables such as more prolonged survival in treated patients.10 While direct comparisons of antifibrotics in IPF and PPF are sparse, emerging data suggest that the benefits of antifibrotics may be smaller in PPF than in IPF. In a study of real-world patients, antifibrotic therapy preserved 562 mL of FVC at 96 months in IPF (−1131.34 mL with antifibrotics vs −1692.8 mL without) and 654 mL in non-IPF PPF (−533.90 mL vs −1187.9 mL). Despite this numerically greater FVC preservation in PPF, overall survival was significantly prolonged only in IPF (P=0.001), with no survival benefit observed in PPF (P=0.3263).11

In this study, participants with PPF were frequently prescribed immunosuppressive therapies to treat underlying systemic disease—especially patients with connective tissue disease—which may have influenced disease progression independently of antifibrotics, making it harder to isolate the effects of antifibrotic treatment.11

Nerandomilast: A Novel Approach

After more than a decade of therapeutic stagnation, the ILD treatment landscape may be on the verge of transformation. Nerandomilast, a selective phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) inhibitor, has demonstrated statistically significant efficacy in slowing lung function decline in patients with IPF, as measured by absolute change in FVC.12 Importantly, this clinical benefit was achieved with a safety and tolerability profile that compares favorably to existing therapies.

After more than a decade of therapeutic stagnation, the ILD treatment landscape may be on the verge of transformation. Nerandomilast, a selective phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) inhibitor, has demonstrated statistically significant efficacy in slowing lung function decline in patients with IPF, as measured by absolute change in FVC.12 Importantly, this clinical benefit was achieved with a safety and tolerability profile that compares favorably to existing therapies.

Since their approvals in 2014, pirfenidone and nintedanib have been associated with significant tolerability challenges, including gastrointestinal side effects, liver enzyme elevations, and photosensitivity reactions, which often lead to dose reductions or treatment discontinuation.7,8,13 Real-world data show that many patients experience continued respiratory symptoms, fatigue, and quality-of-life deterioration despite antifibrotic treatment. As a result, long-term adherence remains a critical challenge, particularly in a population already burdened by progressive disease and polypharmacy, highlighting a need for therapies that are both more effective and better tolerated.3,12,14,15

Mechanism of Action

Nerandomilast is a selective PDE4B inhibitor with antifibrotic and immunomodulatory effects, a dual activity that distinguishes it from existing antifibrotic therapies.16 PDE4B exists in five subtypes (PDE4B1-5); except for PDE4B5, all subtypes are found in lung tissues.17 PDE4B plays a key role in inflammation and fibrosis. Knockout mice lacking PDE4B show impaired T helper 2 (Th2) cytokine production, eosinophil infiltration, and airway hyperreactivity. PDE4B deletion significantly reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) production in monocytes and macrophages and disrupts Th2-cell proliferation. In human lung fibroblasts, PDE4B knockdown inhibits cytokine-induced fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation.17 By intervening at this upstream signaling node, nerandomilast can potentially disrupt the fibrotic cascade while minimizing systemic immune suppression or organ toxicity.17 As such, nerandomilast offers a rationally designed, pathway-specific approach that may potentially reduce side effects and, in turn, improve patient adherence and persistence.

FIBRONEER-ILD Trial

Study Design

The FIBRONEER-ILD trial was a global, Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study enrolling 1176 patients with ILD other than IPF. Importantly, the study was designed to reflect real-world clinical practice by including a heterogeneous, non-IPF ILD population with evidence of radiographic fibrosis and functional decline.18

The FIBRONEER-ILD trial was a global, Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study enrolling 1176 patients with ILD other than IPF. Importantly, the study was designed to reflect real-world clinical practice by including a heterogeneous, non-IPF ILD population with evidence of radiographic fibrosis and functional decline.18

To ensure meaningful representation of patients encountered in routine care, inclusion criteria allowed for a wide range of fibrotic ILDs, with thresholds for lung function (FVC ≥ 45%; diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) ≥ 25%) that support generalizability to both community and academic settings.18

A critical design feature with strategic implications was the stratification of patients based on background nintedanib use. Patients already on a stable dose for ≥ 12 weeks at screening could remain on therapy. Initiation of nintedanib after week 12 was allowed if ILD progressed or acutely worsened. This allowed FIBRONEER-ILD to evaluate nerandomilast’s efficacy and safety both as a monotherapy and as an add-on to existing antifibrotic treatment. This dual-arm relevance enhances nerandomilast’s utility across treatment lines and may support broader clinical adoption. Pirfenidone use was excluded, minimizing treatment overlap and ensuring clarity in assessing nerandomilast as both a monotherapy and an add-on to nintedanib, which is key to understanding the agent’s place in future treatment algorithms.18

Treatment Assignment and Follow-Up

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive nerandomilast 18 mg twice daily, nerandomilast 9 mg twice daily, or placebo. Patients were stratified based on baseline nintedanib use (yes or no) and the results of computed tomography (CT) imaging (usual interstitial pneumonia [UIP] or UIP-like fibrotic pattern vs other fibrotic pattern). Dose reductions and interruptions of background nintedanib therapy and dose interruptions of nerandomilast therapy were permitted to manage adverse events. Visits occurred at baseline; weeks 2, 6, 12, 18, 26, 36, 44, and 52; and at 12-week intervals thereafter. Patients who were still receiving nerandomilast or placebo at the end of the trial were eligible to continue open-label nerandomilast in an extension study. Data have been collected and analyzed through the 52-week visit.18

Efficacy Endpoints and Analyses

The primary endpoint was the absolute change in FVC at week 52. The key secondary endpoint was a composite endpoint comprised of acute exacerbation, hospitalization, and/or death. Safety endpoints included adverse events, with particular focus on those associated with PDE4 inhibitors, such as vasculitis, depression, and suicidality.18

Analyses included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of nerandomilast or placebo. The primary endpoint—change in FVC at week 52—was evaluated using a mixed model for repeated measures, adjusting for treatment, background nintedanib use, CT pattern, and baseline FVC. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random, except for deaths before week 52, where values were imputed using the lowest 10th percentile of observed FVC changes to prevent a bias toward less severe outcomes. Safety outcomes were presented using descriptive statistics.18

Results: Primary Endpoint

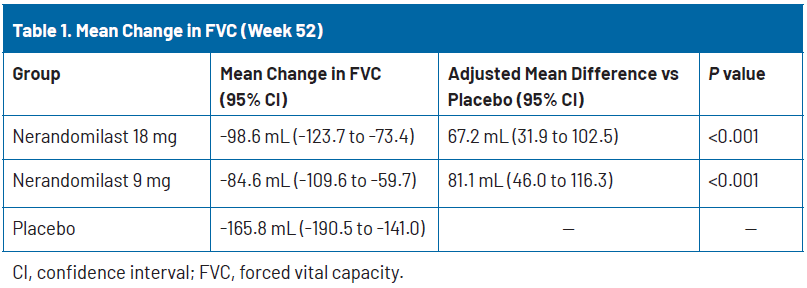

The primary endpoint was met. At week 52, the adjusted mean change in FVC was −98.6 mL (95% confidence interval [CI], −123.7 to −73.4) in the nerandomilast 18 mg group, −84.6 mL (95% CI, −109.6 to −59.7) in the nerandomilast 9 mg group, and −165.8 mL (95% CI, −190.5 to −141.0) with placebo (Table 1). The adjusted difference in FVC between the nerandomilast 18 mg and placebo groups was a statistically significant 67.2 mL (95% CI, 31.9 to 102.5; P<0.001). The adjusted difference between the nerandomilast 9 mg and placebo groups was also statistically significant (81.1 mL [95% CI, 46.0 to 116.3; P<0.001]).18

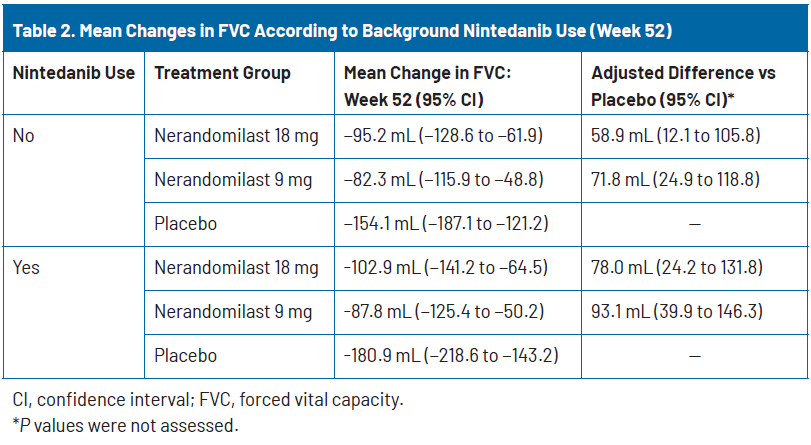

Despite nearly half of the placebo group receiving background nintedanib, a substantial decline in FVC was still observed (−180.9 mL at week 52), consistent with the progressive character of pulmonary fibrosis in these patients. As in the study of nerandomilast for IPF,12 patients on background nintedanib experienced greater FVC decline than those not receiving it (−180.9 mL vs −154.1 mL in the placebo group), possibly due to more advanced disease at baseline, as reflected by their having a longer duration of ILD and lower baseline DLCO. In these very impaired patients, nerandomilast slowed disease progression in both subgroups, showing a treatment difference of +78.0 mL vs placebo in those receiving background nintedanib and +58.9 mL vs placebo in those not receiving background nintedanib (Table 2).18

Key Secondary Endpoints

While the primary endpoint confirmed nerandomilast’s impact on slowing lung function, key secondary outcomes further underscore the agent’s clinical relevance, particularly across the heterogeneous spectrum of PPF.

While the primary endpoint confirmed nerandomilast’s impact on slowing lung function, key secondary outcomes further underscore the agent’s clinical relevance, particularly across the heterogeneous spectrum of PPF.

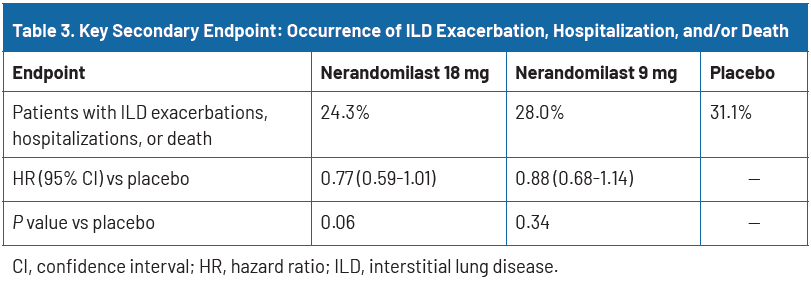

The composite secondary endpoint—time to first ILD exacerbation, respiratory hospitalization, or death—occurred less frequently in both nerandomilast groups compared to placebo: 24.3% in the 18 mg group and 28.0% in the 9 mg group versus 31.1% with placebo. Although differences did not meet the threshold for statistical significance (hazard ratio [HR] 0.77; P=0.06 for 18 mg), the directionally favorable trend across both doses reinforces a consistent treatment effect across clinically meaningful outcomes (Table 3).18

Notably, however, all-cause mortality was substantially lower in both arms versus placebo. A total of 6.1% of patients (24/391) in the nerandomilast 18 mg group and 8.4% (33/393) in the 9 mg group died, compared with 12.8% (50/392) in the placebo group. The HRs for death were 0.48 (95% CI, 0.30–0.79) for nerandomilast 18 mg and 0.60 (95% CI, 0.38–0.95) for 9 mg, translating to a relative reduction in death of over 50% and 40%, respectively, versus placebo.18

Efficacy Across ILD Subtypes

A fundamental strength of the FIBRONEER-ILD trial lies in its broad population, enrolling patients with a wide range of fibrotic ILDs and providing a test of nerandomilast’s utility across the PPF spectrum.

Subgroup analyses demonstrated that the treatment effect of nerandomilast was generally consistent across ILD diagnoses, with adjusted mean FVC changes at week 52 aligning closely with those seen in the overall population. The reproducibility of benefit across these heterogeneous diagnoses reinforces nerandomilast’s broad clinical applicability.18

As discussed earlier, nerandomilast also showed comparable efficacy in patients on and off background nintedanib therapy, suggesting an additive benefit and positioning it flexibly for either monotherapy or as an adjunct to existing antifibrotics. In patients not on nintedanib, nerandomilast 9 mg and 18 mg reduced FVC decline by 71.8 mL and 58.9 mL, respectively, versus placebo. In those on background nintedanib, the adjusted difference versus placebo was even greater: 93.1 mL and 78.0 mL, respectively.18

Taken together, these data support nerandomilast’s potential as a pan-ILD therapy, offering a mechanism-specific option with consistent efficacy across fibrotic ILD subtypes. For payers and health systems, this broad clinical utility may reduce the need for subtype-specific treatment segmentation, simplify therapeutic decision-making, and enable more inclusive access strategies.

Taken together, these data support nerandomilast’s potential as a pan-ILD therapy, offering a mechanism-specific option with consistent efficacy across fibrotic ILD subtypes. For payers and health systems, this broad clinical utility may reduce the need for subtype-specific treatment segmentation, simplify therapeutic decision-making, and enable more inclusive access strategies.

Safety and Tolerability

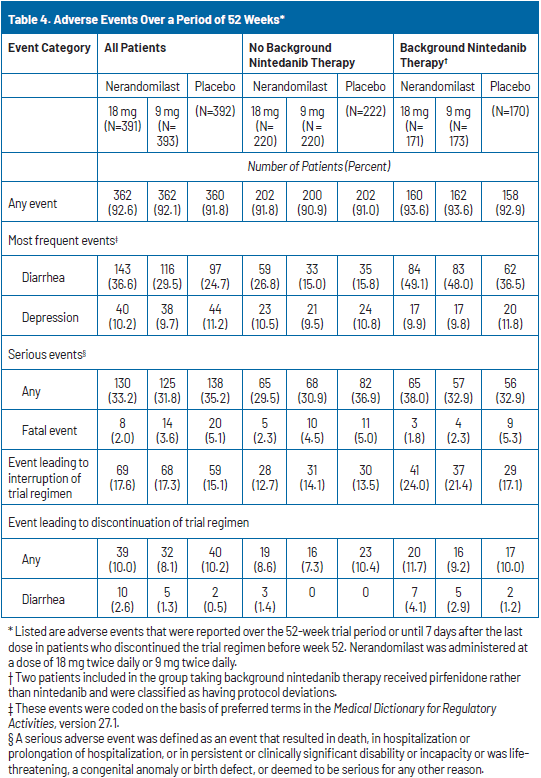

Nerandomilast exhibited a favorable safety profile, with similar rates of adverse events and serious adverse events through week 52 across all treatment groups. Diarrhea was the most common adverse event, occurring in 36.6% of patients receiving nerandomilast 18 mg, 29.5% of those receiving 9 mg, and 24.7% of those receiving placebo. Diarrhea occurred more frequently in patients who were also receiving background nintedanib therapy. However, severe diarrhea was infrequent, reported in 2.1% of the nerandomilast 18 mg group, 1.7% of the 9 mg group, and 1.0% of the placebo group (Table 4). There was no imbalance between the nerandomilast and placebo groups in the incidence of adverse events of interest with PDE4 inhibitors, including vasculitis, depression, and suicidality.18

Adverse events leading to temporary treatment interruption occurred in 17.6%, 17.3%, and 15.1% of the 18 mg, 9 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Permanent discontinuations due to adverse events occurred in 10.0% of the 18 mg group, 8.1% of the 9 mg group, and 10.2% of the placebo group. The most common causes of treatment discontinuation were worsening of pulmonary fibrosis (1.0%, 1.5%, and 3.1%) and diarrhea (2.6%, 1.3%, and 0.5%) across the 18 mg, 9 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Discontinuation rates were similar regardless of whether patients received background nintedanib therapy (Table 4).18

Discussion

Implications for Clinical Practice

The FIBRONEER-ILD trial enrolled a clinically relevant population, including many patients already receiving stable doses of nintedanib at baseline, suggesting ongoing disease progression despite available antifibrotic therapy. In the trial, nerandomilast provided additional FVC preservation in patients no longer receiving antifibrotic treatment and those receiving background nintedanib therapy, supporting its potential role as either monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.18

The FIBRONEER-ILD trial enrolled a clinically relevant population, including many patients already receiving stable doses of nintedanib at baseline, suggesting ongoing disease progression despite available antifibrotic therapy. In the trial, nerandomilast provided additional FVC preservation in patients no longer receiving antifibrotic treatment and those receiving background nintedanib therapy, supporting its potential role as either monotherapy or adjunctive therapy.18

Nerandomilast also demonstrated efficacy across multiple fibrosing ILDs, which supports its potential role as a pan-ILD therapy. By targeting fibrotic and immunologic pathways, nerandomilast may address disease mechanisms common to multiple ILD subtypes, including those with systemic inflammatory components.18

Diarrhea was the most common side effect, but was generally mild and infrequently led to discontinuation, and serious PDE4-related adverse events were not elevated compared to placebo.18 By contrast, existing antifibrotics like pirfenidone and nintedanib are associated with more frequent and severe side effects, often leading to treatment discontinuation.7,8

Taken together, with its unique mechanism of action, tolerability, and consistent efficacy across ILD subtypes, nerandomilast may be positioned in several distinct clinical scenarios:

- As a first-line monotherapy for patients with progressive fibrosing ILD who may be ineligible or intolerant to, or choose to avoid, existing antifibrotics

- As an add-on to nintedanib in patients experiencing disease progression despite stable background therapy, offering them a dual-mechanism approach

- As a sequencing option for patients discontinuing antifibrotic therapy due to side effects

- As a pan-ILD treatment option in clinical settings where diagnostic precision is limited

The trial’s inclusion of patients with documented progression despite prior therapy underscores nerandomilast’s potential utility in real-world PPF management, where disease trajectories are heterogeneous and treatment durability is a concern. Its consistent efficacy across ILD diagnoses and background therapies reinforces its versatility in practice. It suggests that future clinical guidelines may incorporate nerandomilast as a flexible option across lines of therapy and disease subtypes.

In summary, nerandomilast has the potential to fill a critical gap in the ILD treatment armamentarium by expanding therapeutic options, reducing discontinuation rates, and supporting broader disease management strategies aligned with evolving definitions of PPF.

Economic Impact: Payer Considerations

As health care systems face growing pressure to manage rising costs in high-risk populations, payer decision-makers are increasingly focused on therapies that deliver measurable clinical value alongside economic efficiency. The economic burden of PPF is substantial, with acute exacerbations driving disproportionate health care costs. It has been estimated that there is an 80% risk of hospitalization after an exacerbation of ILD,19 which often requires intensive, high-cost care.20 A US insurance claims study reported mean total costs of $77,666 per PPF patient, including $35,364 for claims related to ILD. Of the total expenses, 83.6% were costs associated with hospitalizations.20

As health care systems face growing pressure to manage rising costs in high-risk populations, payer decision-makers are increasingly focused on therapies that deliver measurable clinical value alongside economic efficiency. The economic burden of PPF is substantial, with acute exacerbations driving disproportionate health care costs. It has been estimated that there is an 80% risk of hospitalization after an exacerbation of ILD,19 which often requires intensive, high-cost care.20 A US insurance claims study reported mean total costs of $77,666 per PPF patient, including $35,364 for claims related to ILD. Of the total expenses, 83.6% were costs associated with hospitalizations.20

Nerandomilast may offer meaningful clinical and economic value by slowing functional decline, reducing mortality, and potentially decreasing the frequency of exacerbations that lead to costly hospitalizations. In contrast to existing antifibrotics, which deliver modest incremental benefit at high costs, nerandomilast’s differentiated mechanism and favorable tolerability profile may reduce the need for supportive care and discontinuation-related treatment gaps.

A US-based cost-effectiveness analysis of antifibrotics for IPF found lifetime treatment costs exceeding $675,000, with gains of just 0.32–0.37 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) over symptom management—reflecting incremental cost-effectiveness ratios far above accepted willingness-to-pay thresholds.21 While similar cost-effectiveness analyses for PPF are lacking, evidence suggests the benefit of antifibrotics may be smaller in PPF than in IPF. As noted above, in a study of real-world patients, antifibrotic therapy preserved 562 mL of FVC at 96 months in IPF and 654 mL in non-IPF PPF, with significant prolongation in survival occurring only in patients with IPF.11

A US-based cost-effectiveness analysis of antifibrotics for IPF found lifetime treatment costs exceeding $675,000, with gains of just 0.32–0.37 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) over symptom management—reflecting incremental cost-effectiveness ratios far above accepted willingness-to-pay thresholds.21 While similar cost-effectiveness analyses for PPF are lacking, evidence suggests the benefit of antifibrotics may be smaller in PPF than in IPF. As noted above, in a study of real-world patients, antifibrotic therapy preserved 562 mL of FVC at 96 months in IPF and 654 mL in non-IPF PPF, with significant prolongation in survival occurring only in patients with IPF.11

- Emphasis on potential cost offsets, with modeling to estimate potential cost savings based on reduced exacerbation rates and prolonged time to disease progression, as well as downstream savings opportunities, such as the potential for fewer specialist visits and improved treatment persistence compared to existing antifibrotics.

- Early and proactive engagement with payer decision-makers, particularly to provide budget impact models that reflect real-world hospitalization costs and current resource utilization in the PPF population.

- Generation of real-world evidence to bridge the trial-to-practice gap, including post-approval studies, retrospective claims analyses, outcomes tracking, and partnerships across diverse payer networks to validate trial findings in routine care.

- Exploration of value-based or performance-based contracting models potentially tied to hospitalization reduction, adherence, or FVC stabilization as measurable surrogate endpoints.

By combining its clinical versatility with a mechanism that may reduce health care utilization, nerandomilast is well positioned to address payer concerns around value-based care. Ongoing engagement and real-world validation will be critical to securing access and ensuring appropriate use across the spectrum of fibrotic ILD.

Future Directions

Long-term data will be essential to confirm whether the clinical benefits observed with nerandomilast over 52 weeks translate into sustained clinical and economic value. Patients completing the FIBRONEER-ILD trial are now eligible for an open-label extension study with ongoing 12-week evaluations, providing critical insights into the durability of response, long-term safety, and impact on health care resource utilization.

Long-term data will be essential to confirm whether the clinical benefits observed with nerandomilast over 52 weeks translate into sustained clinical and economic value. Patients completing the FIBRONEER-ILD trial are now eligible for an open-label extension study with ongoing 12-week evaluations, providing critical insights into the durability of response, long-term safety, and impact on health care resource utilization.

Importantly, the extension study may clarify nerandomilast’s role in distinct PPF subgroups, particularly those with complex treatment needs, including unclassifiable fibrosing ILD, where diagnostic uncertainty often limits access to standard antifibrotic therapies.

The extension study may also elucidate nerandomilast’s potential role in patients with rapid functional decline despite prior antifibrotic use who may require combination strategies or in older adults and comorbid patients who may be unable to tolerate existing antifibrotics due to the side effect burden.

Given its targeted PDE4B inhibition and dual antifibrotic–immunomodulatory mechanism, nerandomilast is also well positioned for personalized therapy approaches, including as an adjunctive therapy in patients with incomplete response to monotherapy, as an alternative to patients discontinuing antifibrotics due to tolerability issues, or as a monotherapy in patients with early-stage progressive fibrosis.Examining personalized approaches that account for disease etiology, rate of progression, and comorbidities could help optimize treatment selection and improve outcomes while controlling costs.

Conclusion

Nerandomilast represents a significant advance in the treatment of PPF, addressing a critical unmet need in a patient population with limited therapeutic options and poor prognosis. Its novel mechanism, combining antifibrotic and immunomodulatory effects, alongside demonstrated efficacy in preserving lung function and reducing mortality, positions it as a promising addition to the ILD armamentarium, both as monotherapy and in combination with existing antifibrotics. The favorable safety and tolerability profile further supports its clinical use. However, its potential for longer-term use, value in various PPF patient subpopulations, and impact on patient adherence require confirmation in future research.

Nerandomilast represents a significant advance in the treatment of PPF, addressing a critical unmet need in a patient population with limited therapeutic options and poor prognosis. Its novel mechanism, combining antifibrotic and immunomodulatory effects, alongside demonstrated efficacy in preserving lung function and reducing mortality, positions it as a promising addition to the ILD armamentarium, both as monotherapy and in combination with existing antifibrotics. The favorable safety and tolerability profile further supports its clinical use. However, its potential for longer-term use, value in various PPF patient subpopulations, and impact on patient adherence require confirmation in future research.

Given the substantial and growing burden of fibrosing ILD on patients, health care systems, and society at large, clinicians, payers, and policy makers must prioritize broad, evidence-based access to nerandomilast for patients with progressive and debilitating lung diseases.

Robust clinical data from the FIBRONEER-ILD trial demonstrate nerandomilast’s meaningful impact on slowing disease progression while maintaining a favorable safety profile. To help translate such benefits into real-world patient outcomes, stakeholders must collaborate to develop and implement access strategies that reflect the agent’s demonstrated value. Doing so not only improves long-term clinical outcomes for patients but can also potentially reduce health care resource utilization and associated costs. Proactive, informed decision-making will be critical to ensure the timely availability of nerandomilast, if approved, ultimately shaping a more patient-centered and sustainable approach to managing progressive fibrosing ILD.

References

- Gandhi S, Tonelli R, Murray M, Samarelli AV, Spagnolo P. Environmental causes of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24(22):16481. doi:10.3390/ijms242216481

- Zheng Q, Cox IA, Campbell JA, et al. Mortality and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ERJ Open Res.2022;8(1):00591-2021. doi:10.1183/23120541.00591-2021

- Maher TM, Bendstrup E, Dron L, et al. Global incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2021;22(1):197. doi:10.1186/s12931-021-01791-z

- Raghu G, Chen SY, Hou Q, Yeh WS, Collard HR. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US adults 18-64 years old. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):179-186. doi:10.1183/13993003.01653-2015

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(9):e18-e47. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

- Montero IE, Hernandez-Gonzalez F, Sellares J. Epidemiology and prognosis of progressive pulmonary fibrosis: a literature review. Pulm Ther. 2025;11(3):347-363. doi:10.1007/s41030-025-00302-5

- Espriet (pirfenidone) [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc.; 2023.

- Ofev (nintedanib) capsules [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2024.

- Kou M, Jiao Y, Li Z, et al. Real-world safety and effectiveness of pirfenidone and nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2024;80(10):1445-1460. doi:10.1007/s00228-024-03720-7

- Lee CT, Hao W, Burg CA, Best J, Kolenic GE, Strek ME. The impact of antifibrotic use on long-term clinical outcomes in the pulmonary fibrosis foundation registry. Respir Res. 2024;25(1):255. doi:10.1186/s12931-024-02883-2

- Niitsu T, Fukushima K, Komukai S, et al. Real-world impact of antifibrotics on prognosis in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. RMD Open. 2023;9(1):e002667. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002667

- Richeldi L, Azuma A, Cottin V, et al. Nerandomilast in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(22):2193-2202. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2414108

- Zhao R, Xie B, Wang X, et al. The tolerability and efficacy of antifibrotic therapy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: results from a real-world study. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2024;84:102287. doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2024.102287

- Rajala K, Lehto JT, Sutinen E, Kautiainen H, Myllärniemi M, Saarto T. Marked deterioration in the quality of life of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis during the last two years of life. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):172. doi:10.1186/s12890-018-0738-x

- van Manen MJG, Geelhoed JJM, Tak NC, Wijsenbeek MS. Optimizing quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2017;11(3):157-169. doi:10.1177/1753465816686743

- Aringer M, Distler O, Hoffmann-Vold AM, Kuwana M, Prosch H, Volkmann ER. Rationale for phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition as a treatment strategy for interstitial lung diseases associated with rheumatic diseases. RMD Open. 2024;10(4):e004704. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2024-004704

- Kolb M, Crestani B, Maher TM. Phosphodiesterase 4B inhibition: a potential novel strategy for treating pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220206.doi:10.1183/16000617.0206-2022

- Maher TM, Assassi S, Azuma A, et al. Nerandomilast in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(22):2203-2214. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2503643

- Kreuter M, Belloli EA, Bendstrup E, et al. Acute exacerbations in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis. ERJ Open Res. 2024;10(6):00403-2024. doi:10.1183/23120541.00403-2024

- Olson AL, Maher TM, Acciai V, et al. Healthcare resources utilization and costs of patients with non-IPF progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease based on insurance claims in the USA. Adv Ther. 2020;37(7):3292-3298. doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01380-4

- Dempsey TM, Thao V, Moriarty JP, Borah BJ, Limper AH. Cost‑effectiveness of the anti‑fibrotics for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):18. doi:10.1186/s12890-021-018-0

©2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Consultant360 or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.