Mobile Cardiac Monitoring With Same-Day Discharge After Loading With Intravenous Sotalol is Safe and Effective in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2026;26(2):21-25.

Rohan Mylavarapu, MD1; Zayd Parekh, DO1; Emily Cox, NP2; Weihai Zhan, PhD3; Imdad Ahmed, MD, MBA, CPE, FACC, FHRS, FACP2

1Internal Medicine, Mercyhealth, Rockford, Illinois; 2Mercyhealth System, Illinois and Wisconsin; 3Office of Research, University of Illinois Chicago, Rockford, Illinois

Sotalol is a class III antiarrhythmic agent routinely used for rhythm control in patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation (AF).1 Despite its proven efficacy, sotalol is associated with the risks of QT interval prolongation, bradycardia, and potentially life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias (VAs).1 Consequently, initiation and dose titration have traditionally required inpatient admission with continuous telemetry monitoring until steady-state plasma concentrations and peak QTc intervals are achieved.2 Sotalol loading has been performed almost exclusively with oral administration, which does not reach steady-state levels until the fifth dose, necessitating a minimum of 3 days of hospitalization.2 In 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an intravenous (IV) formulation of sotalol for loading using model-informed pharmacologic data.3 This alternative approach offers the potential to reduce inpatient stays to as little as 24 hours, thereby lowering health care costs and easing operational burdens, particularly in smaller hospitals with limited bed capacity, staffing, and financial resources.4

The PEAKS registry was among the first multicenter studies to evaluate the real-world safety of IV sotalol loading. In this study, patients underwent 24 hours of inpatient monitoring, which included IV loading and completion of 2 oral doses.5 The findings demonstrated a low incidence of proarrhythmic complications, providing early clinical support for IV sotalol as a viable alternative to conventional oral loading protocols.5 Furthermore, the DASH-AF trial suggested steady state drug levels and peak QTc prolongation could be achieved as early as 6 hours after IV administration, sparking interest in same-day discharge (SDD) strategies.6 This study also found that utilization of outpatient mobile cardiac monitoring after SDD resulted in similar QTc prolongation and low rates of complications when compared to traditional multi-day oral initiation.6

While these studies support a shift toward shorter inpatient monitoring periods, additional data on longer-term outcomes, such as 30-day readmission rates, are needed to fully evaluate the safety and practicality of this approach in diverse clinical settings.3,5-6 In this single-center retrospective study conducted at a resource-limited community hospital, we implemented inpatient serial ECG monitoring and 1 week of outpatient Holter monitoring following IV sotalol. We assessed rates of proarrhythmic complications, sotalol discontinuation, and 30-day readmissions. Given the limited evidence on SDD protocols, this study aims to further inform the feasibility, safety, and short-term outcomes of IV sotalol initiation supported by abbreviated inpatient telemetry and extended ambulatory surveillance.

Methods

Patient Selection

This was a retrospective study comprised of patients who underwent IV sotalol infusion for rhythm control between August 2024 to March 2025 at a community tertiary center through the Mercyhealth System. Patients were selected based on age >18 and had normal heart rate (HR) and QTc intervals prior to sotalol infusion.

Sotalol Administration and Monitoring

One electrophysiologist (IA) oversaw all patients during the IV sotalol administration. Forty-four patients with AF were infused with IV sotalol over 1 hour at a dose determined by their creatinine clearance. Oral sotalol was given 4 hours after the start of IV infusion. Electrocardiograms (ECGs) were done every 15 minutes during the infusion, at the start of oral administration, and 2 hours after. These patients underwent a cardioversion or ablation if they remained in AF after the completion of the IV infusion. They were then placed on a mobile cardiac monitor and discharged the same day. The oral dose of sotalol upon discharge was determined by the IV loading dose and creatinine clearance. After discharge, the patients were contacted by the electrophysiologist for the next 2 days prior to their doses in the morning and evening. Their HR and QTc intervals were evaluated, and patients were instructed to either hold or take their prescribed oral dose. Patients were seen in the outpatient clinic 7 days after starting therapy to assess medication tolerance. At this follow-up, patients were offered either ablation or cardioversion if they remained in AF and their respective sotalol dosing was adjusted as well. Measured outcomes included adverse arrhythmic events leading to discontinuation of sotalol, trends of HR and QTc interval with Holter monitoring, 30-day readmission rates, and overall mortality.

determined by their creatinine clearance. Oral sotalol was given 4 hours after the start of IV infusion. Electrocardiograms (ECGs) were done every 15 minutes during the infusion, at the start of oral administration, and 2 hours after. These patients underwent a cardioversion or ablation if they remained in AF after the completion of the IV infusion. They were then placed on a mobile cardiac monitor and discharged the same day. The oral dose of sotalol upon discharge was determined by the IV loading dose and creatinine clearance. After discharge, the patients were contacted by the electrophysiologist for the next 2 days prior to their doses in the morning and evening. Their HR and QTc intervals were evaluated, and patients were instructed to either hold or take their prescribed oral dose. Patients were seen in the outpatient clinic 7 days after starting therapy to assess medication tolerance. At this follow-up, patients were offered either ablation or cardioversion if they remained in AF and their respective sotalol dosing was adjusted as well. Measured outcomes included adverse arrhythmic events leading to discontinuation of sotalol, trends of HR and QTc interval with Holter monitoring, 30-day readmission rates, and overall mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous patient characteristics and outcomes were summarized using means and standard deviations, whereas categorical and dichotomous variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. To assess the statistical significance of changes in HR and QTc interval over specific time periods (eg, from baseline to 60 minutes and from baseline to day 7), the distribution of these changes was first evaluated visually using histograms and P–P plots. Normality was then tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed data, paired Student’s t-tests were used to assess statistical significance, while for non-normally distributed data, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied.

Mixed-effects logistic regression (ie, a generalized linear mixed model with a logit link) was used to assess whether the change (conversion to normal sinus rhythm) was statistically significant, accounting for potential confounders and within-patient correlations across time periods. Patient ID was included as a random intercept to account for repeated measures. For the analysis of 30-day readmissions, Firth’s logistic regression, a bias-reduction method appropriate for small sample sizes, was used to identify associated factors. Only statistically significant covariates were included in the final model, and interactions between covariates were evaluated. Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

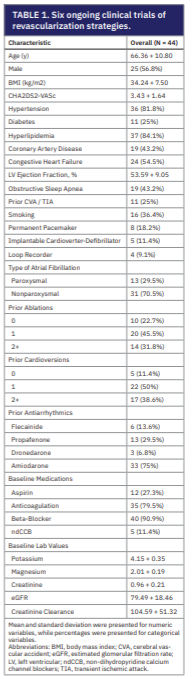

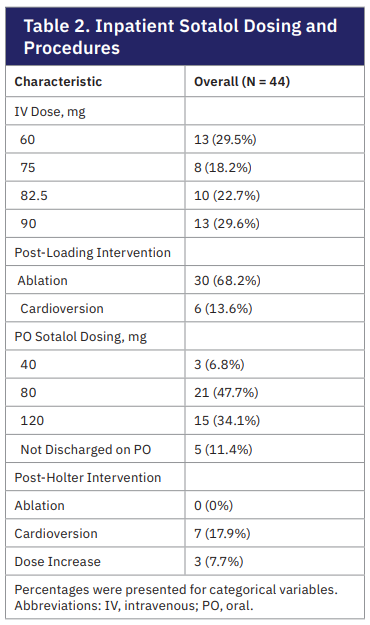

In this retrospective cohort study, 44 patients underwent IV sotalol loading with mobile cardiac monitoring for 7 days between August 2024 to March 2025. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 66.4 + 10.8 years with 56.8% being male. Of all patients, 29.5% had paroxysmal and 70.5% had nonparoxysmal AF. Previous attempts of rhythm control included 77.3% with at least one ablation, 88.6% with at least one cardioversion, and administration of flecainide (13.6%), propafenone (29.5%), dronedarone (6.8%), and amiodarone (75%). Permanent pacemakers were present in 18.2% of patients and loop recorders were in 9.1% of patients. The average creatine clearance was 104.6 + 51.3 and the dose of IV sotalol was determined based on this laboratory value. IV sotalol doses ranged from 60 mg (29.5%), 75 mg (18.2%), 82.5 mg (22.7%), and 90 mg (29.6%). Following IV sotalol infusion, 30 patients (68.2%) underwent ablation and 6 patients (13.6%) underwent cardioversion. For those discharged on oral sotalol after these interventions, twice daily dosing ranged between 40 mg (6.8%), 80 mg (47.7%), and 120 mg (34.1%).

2024 to March 2025. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 66.4 + 10.8 years with 56.8% being male. Of all patients, 29.5% had paroxysmal and 70.5% had nonparoxysmal AF. Previous attempts of rhythm control included 77.3% with at least one ablation, 88.6% with at least one cardioversion, and administration of flecainide (13.6%), propafenone (29.5%), dronedarone (6.8%), and amiodarone (75%). Permanent pacemakers were present in 18.2% of patients and loop recorders were in 9.1% of patients. The average creatine clearance was 104.6 + 51.3 and the dose of IV sotalol was determined based on this laboratory value. IV sotalol doses ranged from 60 mg (29.5%), 75 mg (18.2%), 82.5 mg (22.7%), and 90 mg (29.6%). Following IV sotalol infusion, 30 patients (68.2%) underwent ablation and 6 patients (13.6%) underwent cardioversion. For those discharged on oral sotalol after these interventions, twice daily dosing ranged between 40 mg (6.8%), 80 mg (47.7%), and 120 mg (34.1%).

Outcomes

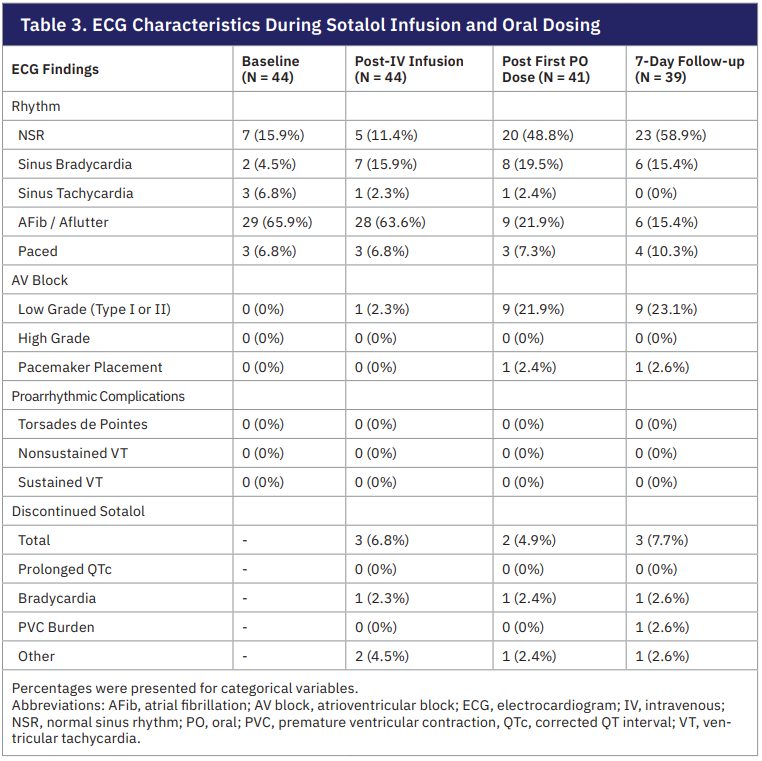

At baseline, the cardiac rhythm among the 44 patients was normal sinus rhythm in 7 (15.9%), sinus bradycardia in 2 (4.5%), sinus tachycardia in 3 (6.8%), AF in 29 (65.9%), and paced rhythm in 3 (6.8%). At the completion of the IV sotalol infusion, 28 patients (63.6%) remained in AF without conversion to normal sinus rhythm. Thirty patients (68.2%) subsequently underwent ablation and 6 patients (13.6%) underwent electrical cardioversion. The first dose of oral sotalol was administered after the respective procedures. At the time of discharge, 7 patients (17.1%) had recurrence of AF. They were discharged on the same dose of sotalol but with a plan for repeat cardioversion at 7-day follow-up. After undergoing cardioversion, 4 patients converted to sinus rhythm and 3 remained in AF. Sotalol doses were increased in those that remained in AF with close follow-up in the outpatient EP clinic.

Proarrhythmic complications were monitored throughout the duration of the study. At baseline, no patients had first-degree and second-degree Mobitz type 1, or high grade (second-degree Mobitz type 2 and third degree) AV blocks. First-degree atrioventricular (AV) blocks were seen in 1 patient (2.3%) after IV infusion, 9 patients (21.9%) after the first oral dose, and 9 patients (23.1%) at 7-day follow-up. After the first oral sotalol dose, 1 patient developed complete heart block and required pacemaker placement. None of the patients had complications such as Torsades de pointes, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), or sustained VT. In total, 8 out of 44 patients required sotalol discontinuation at various points of the study. IV infusion was stopped in 3 patients (6.8%) for symptomatic bradycardia, hypotension from an ejection fraction of 20%, and worsening supraventricular tachycardia. Two patients (4.9%) had completed the IV infusion and tolerated the first oral dose but could not be discharged with the medication for symptomatic bradycardia and hypotension, respectively. Between inpatient discharge to 7-day follow-up, 3 patients (7.7%) were discontinued from oral sotalol for bradycardia, high premature ventricular contraction burden, and symptomatic sinus pause requiring pacemaker placement.

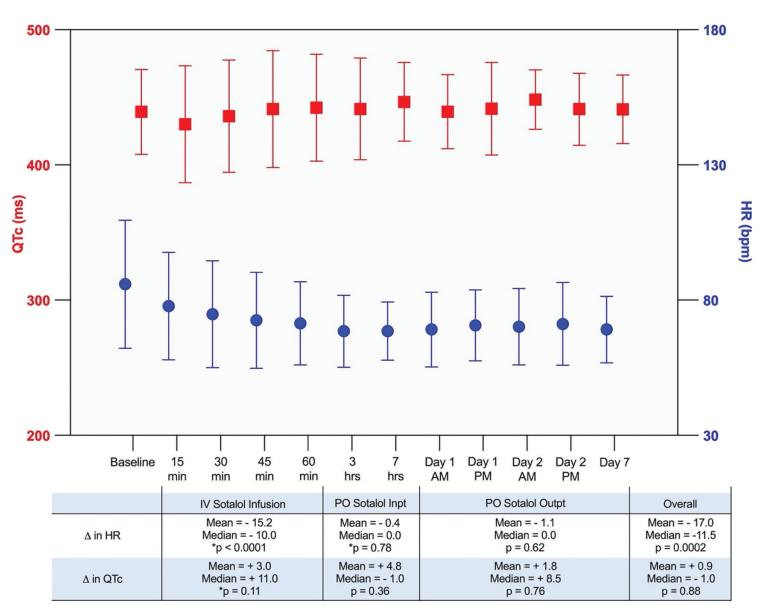

Because sotalol may cause bradycardia and QTc prolongation, serial ECGs during IV infusion, an ECG after the first oral dose, and outpatient Holter monitoring were performed to monitor the HR and QTc interval. The average baseline HR was 85.9 + 23.7 beats per minute (bpm) and QTc was 439.3 + 31.4 ms. At the completion of IV sotalol infusion, the average HR decreased to 71.4 + 15.4 bpm, which was a mean decrease of 15.2 bpm (P<0.0001). There was a nonsignificant increase in QTc to 442.4 + 39.4 ms (P=0.11). Subsequent changes in HR following the first inpatient oral dose and outpatient monitoring were minimal, with a mean drop 0.4 bpm (P=0.78) and 1.1 bpm (P=0.62), respectively. The QTc throughout the same period of monitoring had a mean increase of 4.8 ms and 1.8 ms, reflecting an average of 446.7 + 29.2 ms on discharge from the hospital and 441.2 + 25.4 ms at 7-day follow-up. The overall change in HR from the start of IV loading to the outpatient follow-up was a mean decrease by 17.1 bpm (P=0.0002), with the largest drop occurring during IV infusion. The overall mean increase in QTc was 0.9 ms (P=0.88).

performed to monitor the HR and QTc interval. The average baseline HR was 85.9 + 23.7 beats per minute (bpm) and QTc was 439.3 + 31.4 ms. At the completion of IV sotalol infusion, the average HR decreased to 71.4 + 15.4 bpm, which was a mean decrease of 15.2 bpm (P<0.0001). There was a nonsignificant increase in QTc to 442.4 + 39.4 ms (P=0.11). Subsequent changes in HR following the first inpatient oral dose and outpatient monitoring were minimal, with a mean drop 0.4 bpm (P=0.78) and 1.1 bpm (P=0.62), respectively. The QTc throughout the same period of monitoring had a mean increase of 4.8 ms and 1.8 ms, reflecting an average of 446.7 + 29.2 ms on discharge from the hospital and 441.2 + 25.4 ms at 7-day follow-up. The overall change in HR from the start of IV loading to the outpatient follow-up was a mean decrease by 17.1 bpm (P=0.0002), with the largest drop occurring during IV infusion. The overall mean increase in QTc was 0.9 ms (P=0.88).

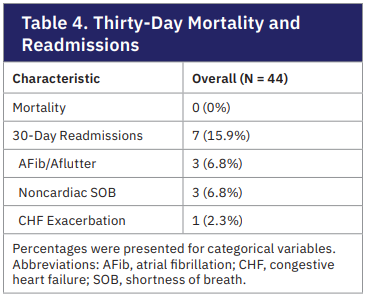

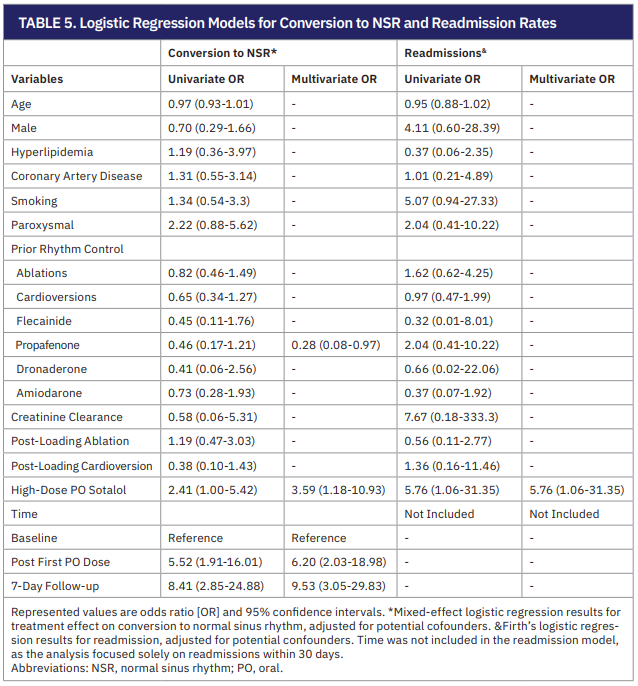

Thirty-Day Complications and Regression Models

Patient mortality and complications were monitored up to 30 days after SDD following IV sotalol loading. The overall mortality was 0%. Seven of 44 patients (15.9%) were readmitted within 30 days for AF recurrence (6.8%), shortness of breath from noncardiac reasons (6.8%), and heart failure exacerbation (2.3%). We additionally performed a generalized linear mixed model to assess the treatment effect on conversion to normal sinus rhythm (NSR) and a Firth’s logistic regression model for readmission rates adjusted for cofounders. These models showed that patients who were on prior propafenone for rhythm control were less likely to convert to NSR after IV sotalol loading and subsequent ablation or cardioversion (OR: 0.28, 95% CI, 0.08-0.97). The odds of converting to NSR among those treated with high-dose oral sotalol (120 mg) were approximately 3.59 times those of patients who received lower does (OR: 3.59, 95% CI, 1.18-10.93). Interestingly, time from IV sotalol loading played an important role in sinus conversion. This was seen in the number of patients in sinus rhythm after the first oral dose and those at 7-day follow-up (OR: 6.20, 95% CI, 2.03-18.98 vs OR: 9.53, 95% CI, 3.05-29.83). The model also showed that patients receiving high-dose oral sotalol were more likely to be readmitted within 30 days of IV infusion for any cause (OR: 5.76, 95% CI, 1.06-31.35).

Abbreviations: Inpt, inpatient; outpt, outpatient.

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study demonstrates that SDD following IV sotalol loading and oral maintenance therapy is a safe, feasible, and effective strategy for managing atrial arrhythmias. Real-time Holter monitoring at discharge enabled dynamic assessment of QTc and HR, allowing for timely intervention when needed. Importantly, this is the first study to evaluate 30-day hospital readmission rates following this initiation protocol, further validating its safety. The combination of structured outpatient monitoring and low complication rates supports the broader adoption of this approach, especially in community hospitals where inpatient resources may be constrained.

These findings are particularly relevant given the limitations of traditional oral sotalol initiation, which historically required a 3-day inpatient stay to achieve plasma steady-state levels that are primarily influenced by renal function.1-3 However, oral loading introduces considerable variability due to unpredictable factors such as gastrointestinal absorption, food intake, and body habitus. These variables are especially problematic in patients with obesity or congestive heart failure (CHF), who are already at increased risk for VAs.7-9 IV sotalol mitigates these limitations by offering a more consistent and controlled pharmacokinetic profile. In our cohort, comprised predominantly of patients with obesity and CHF, IV loading proved to be both safe and effective. These findings align with prior studies like DASH-AF and PEAKS, though our population had a notably higher burden of CHF.5,6 Taken together, this suggests that IV sotalol may offer a superior and more predictable loading strategy when compared to oral options.

Building on this, our rhythm control outcomes were clinically meaningful. While 63.6% of patients remained in AF immediately following IV loading, most converted to sinus rhythm after ablation or cardioversion and initiation of oral sotalol. By day 7, nearly 59% were in sinus rhythm, with only 15.4% in recurrent AF. These findings highlight the value of IV sotalol for both preprocedural stabilization and postprocedural rhythm support. Logistic regression identified several important predictors of conversion. Patients treated with high-dose oral sotalol (120 mg BID) had significantly greater odds of achieving sinus rhythm, while those previously treated with propafenone were less likely to convert, suggesting a more refractory arrhythmic phenotype. Notably, the odds of conversion increased substantially between the inpatient phase and 7-day outpatient follow-up (OR 6.20 vs 9.53). This delayed benefit underscores that sotalol’s full therapeutic effect may continue to evolve after discharge.

sinus rhythm after ablation or cardioversion and initiation of oral sotalol. By day 7, nearly 59% were in sinus rhythm, with only 15.4% in recurrent AF. These findings highlight the value of IV sotalol for both preprocedural stabilization and postprocedural rhythm support. Logistic regression identified several important predictors of conversion. Patients treated with high-dose oral sotalol (120 mg BID) had significantly greater odds of achieving sinus rhythm, while those previously treated with propafenone were less likely to convert, suggesting a more refractory arrhythmic phenotype. Notably, the odds of conversion increased substantially between the inpatient phase and 7-day outpatient follow-up (OR 6.20 vs 9.53). This delayed benefit underscores that sotalol’s full therapeutic effect may continue to evolve after discharge.

The PEAKS registry demonstrated that peak pharmacodynamic effects of sotalol loading occur during the IV infusion phase.5 Consistent with their findings, we observed a significant reduction in heart rate during infusion (mean drop of 15.2 bpm, P<0.0001), with minimal additional changes after oral dosing. QTc prolongation was mild and nonsignificant, with a net mean increase of just 0.9 ms from baseline to day 7 (P=0.88), suggesting a low proarrhythmic risk when patients are carefully monitored. Although 7 patients developed sinus bradycardia during infusion, only one required discontinuation, and the incidence of high-degree AV block and VAs remained low. We also expanded on the ambulatory monitoring protocols used in the DASH-AF trial by extending the observation period to 7 days post-discharge. During this period, only one patient developed complete heart block requiring pacemaker implantation.6

Our study is the first to quantify 30-day readmission rates following same-day IV sotalol initiation. The overall readmission rate was 15.9%, driven primarily by AF recurrence, dyspnea, and CHF exacerbations. High-dose oral sotalol was associated with higher odds of readmission, possibly reflecting greater underlying arrhythmic burden or increased sensitivity to the drug. Despite this, there were no cases of Torsades de pointes, sustained VAs, or deaths. Although 18.2% of patients discontinued sotalol due to bradycardia, hypotension, or arrhythmic events, these complications were identified and addressed promptly to prevent lasting morbidity and mortality. Taken together, our findings reinforce that IV sotalol loading, followed by early discharge and structured outpatient monitoring, is a safe and effective strategy for rhythm control. The predictable hemodynamic profile, favorable safety outcomes, and manageable readmission rates support broader implementation of this protocol, including in resource-limited community hospital settings.

Finally, this study underscores the potential cost-effectiveness of IV sotalol loading in community hospitals. Traditional oral initiation protocols are associated with costs exceeding $3000, more than half of which stems from room and board.4,10 In contrast, IV loading can shorten hospital stays by at least one day, with projected savings of up to $3800 per patient.11 Moreover, recent data show that patients initiated on IV sotalol have significantly shorter hospitalizations than those receiving oral loading (1 day vs 3.6 days, P<0.001), without any increase in adverse drug events like bradycardia or QT prolongation.12 This makes IV sotalol a cost-conscious, resource-efficient option for rhythm control.

Limitations

Several limitations exist regarding the study performed. First, the generalizability of the study findings may be limited given the nonrandomized nature of this retrospective cohort single-center study. Due to the inherent nature of the study design being an observational study, there is always a risk of selection bias and inability to establish causality. Second, the limited sample size may underestimate the adverse outcomes observed. For example, in the multivariate analysis performed, the high oral dose of sotalol was associated with both conversion to NSR and readmission to the hospital; however, the confidence intervals for both findings were extremely wide. This suggests that future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to assess rates of adverse outcomes and their associated factors.

Conclusions

The study performed suggests that SDD with outpatient cardiac monitoring after loading with IV sotalol can be a safe and effective alternative that reduces hospital length of stay. This strategy can reduce resource and hospital bed utilization in a community hospital. Further multicenter research with larger scale patient population will be necessary to further validate these findings.

Disclosures: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Alboni P, Razzolini R, Scarfò S, et al. Hemodynamics effects of oral sotalol during both sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(5):1373-1377. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(93)90545-c

- Chung MK, Schweikert RA, Wilkoff BL, et al. Is hospital admission for initiation of antiarrhythmic therapy with sotalol for atrial arrhythmias required? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(1):169-176. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00189-2

- Somberg JC, Vinks AA, Dong M, Molnar J. Model-informed development of sotalol loading and dose escalation employing an intravenous infusion. Cardiol Res. 2020;11(5):294-304. doi:10.14740/cr1143

- Varela DL, Burnham TS, May H, et al. Economics and outcomes of sotalol in-patient dosing approaches in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2022;33(3):333-342. doi:10.1111/jce.15342

- Steinberg BA, Holubkov R, Deering T, et al. Expedited loading with intravenous sotalol is safe and feasible – primary results of the Prospective Evaluation Analysis and Kinetics of IV Sotalol (PEAKS) Registry. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21(7):1134-1142. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.02.046

- Lakkireddy DJ, Ahmed A, Atkins D, et al. Feasibility and safety of intravenous sotalol loading in adult patients with atrial fibrillation (DASH-AF). JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2023;9(4):555-564. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2022.11.026

- Shaikh F, Wynne R, Castelino RL, et al. Effect of obesity on the use of antiarrhythmics in adults with atrial fibrillation: a narrative review. Clin Cardiol. 2024;47(8):e24336. doi:10.1002/clc.24336

- Hanyok JJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sotalol. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(4):A19-A26. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(93)90021-4

- Huang CY, Overholser BR, Sowinski KM, et al. Arrhythmias in patients with heart failure prescribed dofetilide or sotalol. JACC Adv. 2024;3(11):101354. doi:10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.101354

- Kim MH, Klingman D, Lin J, Pathak P, Battleman D. Cost of hospital admission for antiarrhythmic drug initiation in atrial fibrillation. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(5):840-848. doi:10.1345/aph.1l698

- DelGrosso K, Wood K. Establishing an intravenous sotalol loading program. Heart Rhythm O2. 2024;6(2):233-236. doi:10.1016/j.hroo.2024.11.011

- Liu AY, Charron J, Fugaro D, et al. Implementation of an intravenous sotalol initiation protocol: implications for feasibility, safety, and length of stay. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2023;34(3):502-506. doi:10.1111/jce.15819