Bachmann’s Bundle Pacing: A New Approach for Decreasing Atrial Fibrillation Incidence?

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2026;26(1):10-12.

Linda Moulton, RN, MS

Faculty: Order and Disorder EP Training Program, Critical Care ED/CCE Consulting, Calistoga, California

In the field of cardiac pacing, the concept has evolved that pacemaker leads positioned to pace portions of the cardiac conduction system provide greater benefit than leads placed in other cardiac tissue areas, representing a shift toward a physiologic pacing approach. Recently, considerable attention has been directed toward lead placement within the ventricular conduction system.1,2 Pacing a portion of the cardiac conduction system to normalize electrical flow through the heart helps prevent conduction delay, which can lead to new arrhythmias. Attention has now turned to the right atrium (RA), with interest in using Bachmann’s bundle (BB) for atrial pacing. This paper will review the role of right atrial appendage (RAA) pacing and its consequences, and the emerging evidence for a change to BB pacing in the atria.

Background

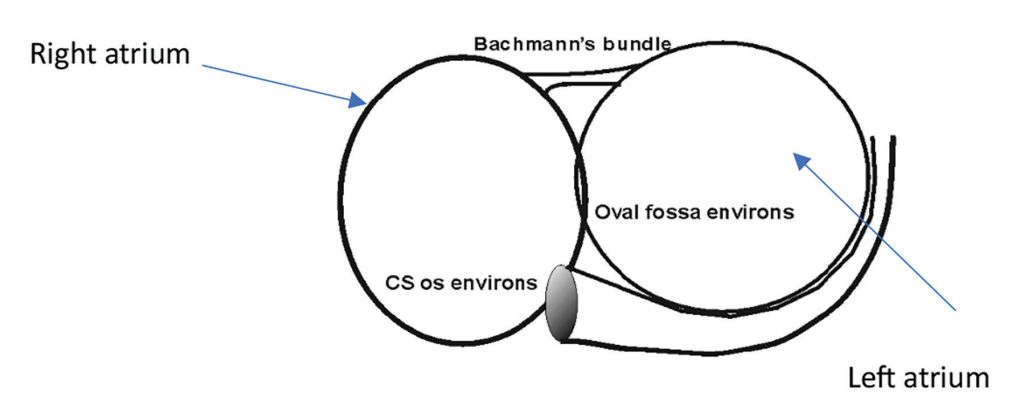

BB is one of the accessory conducting pathways and plays a major role in interatrial conduction, preferentially conducting from the RA to the left atrium (LA). It is a

Used with permission from the Order and Disorder EP Training Program.

circumferential muscle bundle located at the anterior wall of the LA. BB is a direct continuation of the terminal crest (crista terminalis), which separates the systemic venous sinus of the RA from the RAA. It extends into fibers within the anterior and posterior LA, anteriorly toward the LA appendage and posteriorly toward the pulmonary veins. The tissue type is similar to that of the atrioventricular node and His-Purkinje system, but without insulating tissue being present3-5 (Figure 1).

Van der Does et al6 examined conduction disturbances and unipolar voltage changes in BB associated with aging in subjects aged 36 to 83 years. They observed age-related increases in conduction abnormalities, generalized conduction slowing, and the presence of low-voltage areas. Lateral uncoupling at BB appeared to increase with advancing age, leading to P-wave prolongation and a higher likelihood of development of atrial fibrillation (AF). In a 2003 study, a 30-month follow-up of 16 patients with interatrial conduction block showed that 8 developed AF.7

RAA pacemaker lead placement has been performed for 50 years. This was historically favored because it was considered easier to accomplish procedurally,8 although it carries a risk of atrial perforation. However, the lateral location of the RAA can result in atrial conduction delays and P-wave prolongation. This activation delay has been associated with an increased risk of AF and atrial electromechanical dysfunction.7,9

As early as 2000, the RAA pacing site was being challenged. In a study from Yu et al10 that year, pacing at various RA sites demonstrated that RAA pacing produced the longest P wave. In 2001, Bailin et al11 reported a multicenter, prospective, randomized study comparing BB pacing with RAA pacing in patients with recurrent paroxysmal AF. Patients with BB pacing demonstrated shorter P-wave durations and a higher (P<0.05) rate of survival free from chronic AF at 1 year (75% vs 47% for RAA pacing). The BB area was identified without intracardiac recordings or echocardiographic guidance. The targeted lead placement site was a segment of the septum at the junction of the anterior septum and atrial roof, with the BB pacing location defined fluoroscopically.

Also in 2001, Roithinger et al12 studied 28 patients after radiofrequency ablation for supraventricular arrhythmias. Pacing was performed using standard multipolar catheters from the presumed insertion site of BB, the coronary sinus os, the high lateral RA, and the RAA. Total atrial activation time was significantly shorter with BB pacing compared with the other sites, suggesting the potential for AF prevention. In 2002, Gozolits et al13 used a 65-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) to pace 15 patients from the high RA, CS os, distal CS, high RA septum, and dual sites. Endocardial atrial activation time and P-wave duration were measured, with the shortest P-wave duration observed at the high septal (BB) area. The authors concluded that BB pacing may be beneficial in patients with AF.

In 2022, Infield et al14 reported a retrospective study comparing BB pacing versus RA septal pacing. The 2 lead positions were defined by fluoroscopic lead position and P-wave criteria. BB pacing was associated with a decrease in atrial arrhythmia burden, recurrence, and new incidence. The authors suggested the need for a prospective, randomized study. In 2024, Yoshimoto et al15 compared interatrial conduction delay during BB pacing and RAA pacing using biatrial strain rate echocardiography. BB pacing was defined by ECG criteria plus P-wave duration shortening. Mechanical synchronization between the RA and LA observed with BB pacing was comparable to that seen in sinus rhythm.

However, it may be that a single pacing site does not suit all patients. Van Schie et al16 investigated the optimal RA pacing site and suggested that it may vary among patients, indicating that the ideal site should be individually selected.

New Lead Placement Strategies

The goal in identifying a new location for atrial lead placement is to reduce the window of vulnerability during which an ectopic beat may initiate AF. Two major concerns regarding BB pacing are procedural technique and verification of location. In a 2002 animal study, investigators suggested that the optimal pacing site was the middle BB.17 This was followed in 2005 by Bailin’s early description of the technique for atrial lead implantation in BB.18 More recently, Lustgarten et al19 published a detailed step-by-step description of the BB lead implant/placement technique and, in 2025, proposed that the optimal pacing site is at the inferoseptal SVC at the RA junction.20

Verification of the BB location during implantation has been achieved through various methods. Early studies defined BB pacing fluoroscopically.11 In 2008, Saremi et al4 reported that BB and its vascular supply could be identified on cardiac computed tomography, but were less easily seen in patients with severe coronary artery disease or abnormal ECG findings. A 2022 case series used fluoroscopic and electrical mapping to identify the endocardial electrogram signature of the BB region and associated BB potentials.21 P-wave axis and morphology, along with the local electrogram signal at or near BB, were also used for localization. In 2025, investigators

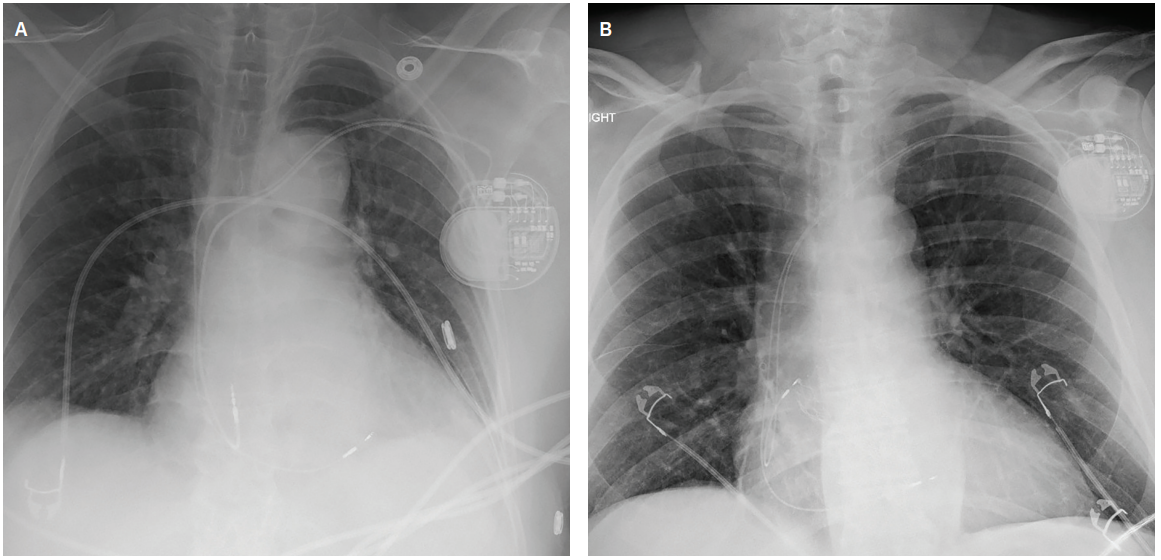

(Images provided by Zachary Hollis MD, personal communication, October 2025. Images courtesy of Zachary Hollis MD, used with permission.)

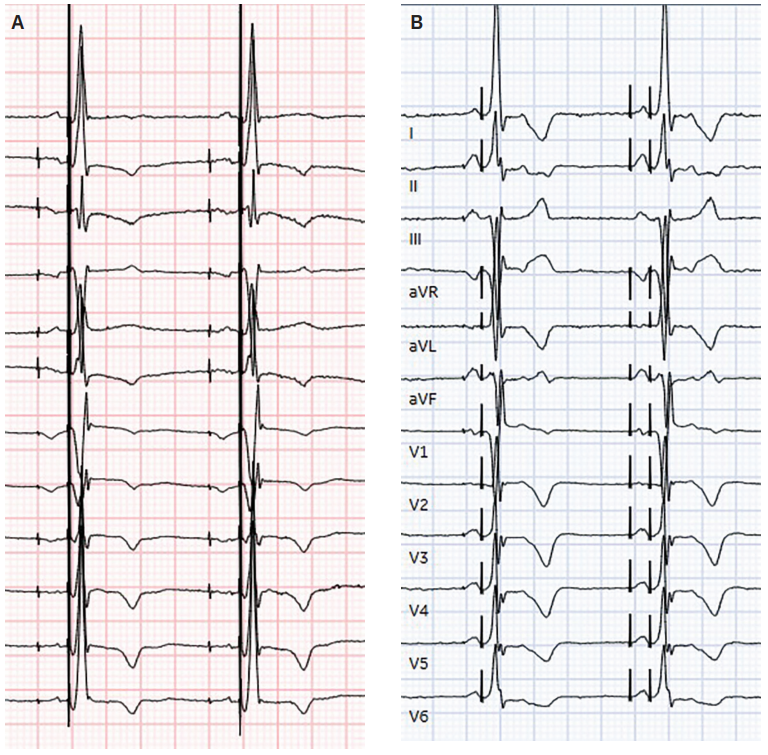

evaluated electrogram-guided BB pacing using sheath-assisted, stylet-driven atrial lead implantation.22 They incorporated 12-lead P-wave morphology and electrogram analysis, recorded BB potentials in most patients, and performed threshold testing that demonstrated BB capture in >80%. (Figure 2)

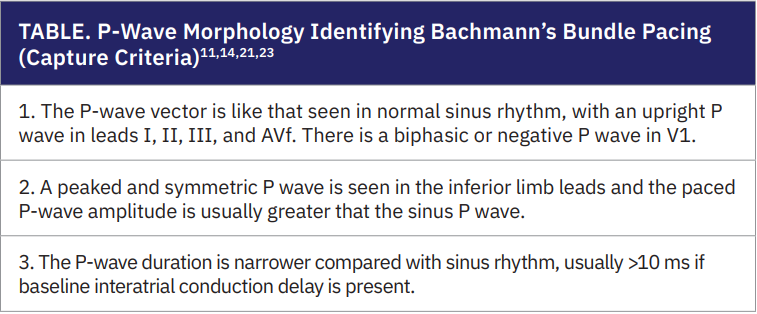

Several authors have reported consistent observations regarding P-wave morphology that characterize BB pacing (capture criteria)11,14,21,23 These include: a P-

Images provided by Zachary Hollis MD, personal communication, October 2025. Images courtesy of Zachary Hollis MD, used with permission.

wave vector similar to that seen in normal sinus rhythm, with an upright P wave in leads I, II, III, and aVF; a biphasic or negative P wave in V1; a peaked and symmetric P wave in the inferior limb leads, with paced P-wave amplitude typically greater than that of the sinus P wave; and a shorter P-wave duration compared with sinus rhythm, usually >10 ms when baseline interatrial conduction delay is present. (Table, Figure 3)

Extending this concept further, 2 recent case reports described the implantation of a wireless atrial pacemaker within BB.24,25

In addition to reducing the incidence of AF, BB pacing may also provide benefits for patients with heart failure. Subramanian et al23 examined the effects of BB pacing in patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction plus interatrial delay on ECG; they found that BB pacing resulted in improved NT-proBNP levels, exercise capacity, and diastolic function. In another study, Saga et al26 found that BB pacing achieved a higher percentage of left ventricular synchronized pacing compared with RAA pacing, offering potential advantages for patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Conclusion

BB pacing represents a new approach for reducing the incidence of AF. Compared with RA septal or RAA pacing, BB pacing has been associated with reductions in AF burden, recurrence, and initiation, and evidence suggests BB pacing is preferable to RAA pacing.

Utilizing the heart’s intrinsic conduction system for pacing (the interstates, going fast!) may be preferable to pacing random muscle tissue (the local roads, always slower!). Conduction times are decreased, and fewer pacing iatrogenic complications may occur. BB pacing represents another promising strategy to reduce the burden of AF in patients requiring pacing. The field of pacing continues to evolve, and further large-scale studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Disclosures: The author has completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reports stock in Medtronic, Johnson & Johnson MedTech, and Boston Scientific.

References

- Lewis AJM, Foley P, Whinnett Z, Keene D, Chandrasekaran B. His bundle pacing: a new strategy for physiological ventricular activation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(6):e010972. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.010972

- Huang W, Chen X, Su L, et al. A beginner’s guide to permanent left bundle branch pacing. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(12):1791-1796.

- Khaja A, Flaker G. Bachmann’s bundle: does it play a role in atrial fibrillation? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28(8):855-863. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00168.x

- Saremi F, Channual S, Krishman S, et al. Bachmann’s bundle and its arterial supply: imaging with multidetector CT-implications for interatrial conduction abnormalities and arrhythmias. Radiology. 2008;248(2):447-457. doi:10.1148/radiol.2482071908

- Anderson RH, Sutton R, Sánchez-Quintana B. Bachmann’s bundle: how anatomists and electrophysiologists see it. Heart Rhythm. 2025 May 8:S1547-5271(25)02412-9. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.04.064

- van der Does WFB, Houck CA, Heida A, et al. Atrial electrophysiological characteristics of aging. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2021;32(4):903-912. doi:10.1111/jce.14978

- Agarwal YK, Aronow WS, Levy JA, Spodick DH. Association of interatrial block with development of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(7):882. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00027-4

- Duong NC, Yang Z, Iaizzo PA. Anatomic, electrical, and hemodynamic characterization of Bachmann bundle in the swine heart. Heart Rhythm. 2025 May 8:S1547-5271(25)02341-0. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.04.022

- Goyal SB, Spodick DH. Electromechanical dysfunction of the left atrium associated with interatrial block. Am Heart J. 2001;142(5):823-827. doi:10.1067/mhj.2001.118110

- Yu WC, Tsai CF, Hsieh MH, et al. Prevention of the initiation of atrial fibrillation: mechanism and efficacy of different atrial pacing modes. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23(3):373-379. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb06764.x

- Bailin ST, Adler S, Guidici M. Prevention of chronic atrial fibrillation by pacing in the region of Bachmann’s bundle: results of a multicenter randomized trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12(8):912-917. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00912.x

- Roithinger FX, Abou-Harb M, Pachinger O, et al. The effect of the atrial pacing site on the total atrial activation time. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24(3):316-322. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00316.x

- Gozolits S, Fischer G, Berger T, et al. Global P wave duration on the 65-lead ECG: single-site and dual-site pacing in the structurally normal human atrium. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13(12):1240-1245. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.01240.x

- Infeld M, Nicoli CD, Meagher S, et al. Clinical impact of Bachmann’s bundle pacing defined by electrocardiographic criteria on atrial arrhythmia outcomes. Europace. 2022;24(9):1460-1468. doi:10.1093/europace/euac029

- Yoshimoto D, Sakamoyo Y, Uemura Y, et al. Comparative assessment of interatrial conduction delay during Bachmann’s bundle pacing and right atrial appendage pacing using biatrial strain rate echocardiography. Heart Rhythm. 2024 Dec 15:S1547-5271(24)03661-0. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm2024.12.016

- van Schie MS, Misier NR, Knops P, et al. Mapping-guided atrial lead placement determines optimal conduction across Bachmann’s bundle: a rationale for patient tailored pacing therapy. Europace. 2023;25(4):1432-1440. doi:10.1093/europace/euad039

- Duytshaever M, Danse P, Eysbouts S, Allessie M. Is there an optimal pacing site to prevent atrial fibrillation? An experimental study in the chronically instrumented goat. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13(12):1264-1271. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.01264.x

- Bailin SJ. Atrial lead implantation in the Bachmann bundle. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(7):784-786. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.03.006

- Lustgarten DL, Habel N, Sanchez-Quintana B, et al. Bachmann’s bundle pacing. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21(9):1711-1717. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.03.1786

- Lustgarten DL, Habel N, Infeld M, et al. The Bachmann bundle pacing target: retrograde mapping and microstructural correlation. Heart Rhythm. 2025 Apr 30:S1547-5271(25)02319-7. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.04.012

- Infield M, Habel N, Wahlberg K, et al. Bachmann’s bundle potential during atrial lead placement: a case series. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19:490-494. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.04.012

- Subramanian M, Yalagudin S, Saggu D, et al. Electrogram-guided Bachmann bundle area pacing to correct interatrial block: initial experience, safety, and feasibility. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22(4):1064-1070. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.08.024

- Subramanian M, Yalagudin S, Saggu DK, et al. Accelerated Bachmann bundle area pacing for atrial resynchronization in patients with non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized crossover trial. Heart Rhythm. 2025 Jul 25:S1547-5271(25)02709-2. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.07.028

- Bailin SJ, Vargas G, Powers EM, Dominic P. A wireless atrial pacemaker at Bachmann bundle. HeartRhythm Cas Rep. 2025. doi:10.1016/j.hrcr.2025.07.016

- Hollis Z, Yang E, Ryu K, et al. Leadless atrial pacing targeting Bachmann’s bundle for atrial resynchronization. JACC Case Rep. 2025;30(20):104083. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2025.104083

- Saga AU, Gurshaun R, Vedage N, et al. C1-499644-003 Bachmann’s bundle pacing is associated with increased LV synchronized pacing delivery in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22(4):S16. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.03.034