Empowering Shared Decision-Making in ICD Therapy: Interview With Melanie S Sulistio, MD, on a Novel Decision-Aid

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2025;25(6):25-26.

Interview by Jodie Elrod

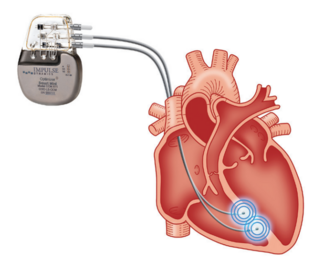

In this interview, EP Lab Digest speaks with Melanie S Sulistio, MD, about her research1 developing a decision-aid to better align patients’ implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock status with goals of care. Dr Sulistio discusses the motivation behind creating this patient-centered tool, the shifting conversations between patients and providers regarding end-of-life care, and the potential impact this decision-aid could have on clinical practice. Dr Sulistio is a Professor of Medicine in the Department of Internal Medicine’s Division of Cardiology at UT Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center.

Before we get into the details of your recent work, could you start by telling us about your background and role at UTSW? You have been deeply involved in both clinical cardiology and medical education—how have those dual passions shaped your approach to patient-centered initiatives like this ICD decision-aid project?

Before we get into the details of your recent work, could you start by telling us about your background and role at UTSW? You have been deeply involved in both clinical cardiology and medical education—how have those dual passions shaped your approach to patient-centered initiatives like this ICD decision-aid project?

Thank you for your interest in my background. Since starting as faculty at UTSW in 2009, I have been intently focused on medical education. This is evident by some of the roles I have held, including Simulation Director for Internal Medicine (IM) Residency, Associate Program Director (APD) of the IM Residency, APD of the Cardiovascular Fellowship, and then Associate Dean of Student Affairs for the medical school. Concurrently, I built my general cardiology practice and attended on Cardiac ICU (CICU) rotations. However, my passion for teaching in medicine has always been rooted in ensuring future physicians and physicians in training provide the best, most excellent, compassionate patient-centered care. Daily encounters with major gaps in both education and clinical care, particularly around communication, provoked significant frustration. I used that frustration to fuel the work I have done around aligning ICD shock settings with patients’ goals of care, particularly when having major changes in quality of life or at end of life. This not only allowed me to address a major gap in our system/care that led to one patient being shocked 28 times, unbeknownst to anyone because of recent onset aphasia from an embolized left ventricular thrombus/cerebrovascular accident, but it also allowed me to lead a team of learners in an effort to continuously improve patient care, something I believe we should all be doing in medicine. Now, it is the nidus for my initiation of a new primary palliative/cardiology clinic.

This project reflects a major interdisciplinary effort between UTSW and the Parkland Center of Innovation and Value. What inspired your team to develop this decision-aid video, and how did you identify the need for it among patients with ICDs?

The patient who I mentioned above and cared for in the CICU inspired the entirety of this work. When it became evident that she had been shocked 28 times while conscious, causing significant pain and suffering, it prompted my investigation into patients’ knowledge of their ICDs, clinicians’ viewpoints, and practice around discussing ICD settings, leading to my discovery of the absence of processes within our system to ensure patient ICD shock status is aligned with their goals of care, particularly at end of life and at times of major changes in quality of life. It began with a review paper,2 which led to investigation that ICD educational tools have little to no diversity,3 and then surveying Parkland patients with ICDs who had been referred to palliative care to discover knowledge levels.4 We found that in this safety-net diverse population with many barriers to care, their ICD knowledge was far lower than what had been previously reported in primarily white populations. This made it clear we needed to make an ICD educational tool designed specifically for our Parkland patients to help close this knowledge gap and empower them to make informed decisions regarding their ICD.

Can you share more about how you approached creating patient-centered, accessible content—especially for a diverse population facing language and health literacy barriers?

We knew we would adhere to Parkland guidance regarding literacy level based on the wonderful work they do every day creating patient content, which at the time was third-grade level or lower. It was also important that the content be narrated by actual Parkland patients with ICDs. Finally, a Spanish version was critical to make the content as accessible as possible for Parkland patients.

On our team, we had Christine Chen, MD, who at the time was still a medical student; she is an artist and created the animation. Stakeholders on the steering committee from various specialties (electrophysiology, general cardiology, congestive heart failure, and pallliative care) helped create and modify the script. Under the great leadership of our cardiovascular fellow at the time, Mark Berlacher, MD, we filmed the content with the help of Kristin Alvarez, PharmD, BCPS, and the Parkland Center of Innovation and Value.

Your study showed a significant increase in patients’ understanding of ICD function after watching the video. What surprised you most about the patient feedback or learning outcomes?

Many things surprised us. The first was how dramatic the acquisition of knowledge affected the patients. One young woman told us she had been fearful to hold her children for fear they would be shocked, and the video comforted her by showing her that she could indeed safely hold her children. Some patients asked us why they had not been given information like this video before their device implantation, which had been performed at other institutions. Across the board, patients thought the video was helpful.

Advance care planning involving ICD management is often overlooked. How do you see this video shifting conversations between patients and providers—particularly for those approaching end-of-life care?

Thank you for bringing up this important gap in our medical care. My hope is that this video can be used as an effective tool to empower patients with knowledge so they can have informed conversations with their clinicians. Not only is this video compassionate for patients by giving them information, but it is also intended to be compassionate to clinicians who are often hard-pressed for time, especially in overstressed systems such as safety-net hospital systems. It allows them to share the video with their patients, saving precious time for the critical conversation between patient and clinician, and offering shared decision-making regarding ICD shock status.

Looking ahead, how do you envision this tool being integrated into clinical workflows at scale, and what lessons can other institutions take from your team’s approach to implementing patient-centered education?

We had hoped that we could use this on a larger scale by pushing the video out via MyChart, but this has proved to be ineffective, as studied by Carla McStay, MD, from UTSW and presented at the 2025 Annual Assembly of Hospice and Palliative Care,5 presented by the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. Patients are simply not as engaged as we had hoped with their MyChart communication, for understandable reasons. However, we hope to effectively use the video in the outpatient clinics during wait times (eg, some of our providers have already adopted this, both in cardiology and palliative care clinics) and for inpatients to view in their rooms during admissions. Some important lessons for others to consider are: (1) understanding the critical nature of clinician buy-in for its use; (2) easily accessing the video via QR code and making it a part of internal processes (ie, to consider automatic addition to discharge paperwork if the patient has an ICD on the problem list; and (3) taking the time to understand current state of where it can be most effectively used.

References

1. Chen CL, Godfrey S, Newcomer K, et al. Development of an innovative decision-aid to better align patients’ implantable cardioverter defibrillator shock status with goals of care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2025;18(3):e011544. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.124.011544

2. Khera R, Pandey A, Link MS, Sulistio MS. Managing implantable cardioverter-defibrillators at end-of-life: practical challenges and care considerations. Am J Med Sci. 2019;357(2):143-150. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.11.016

3. Abousaab C, Chen C, Suarez A, et al. Charging…everybody clear?: A look at accessibility of content in implantable cardioverter defibrillator patient resources. Am J Med Sci. 2022;364(1):124-126. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2022.01.017

4. Berlacher M, Abousaab C, Chen C, et al. ICD knowledge and attitudes at end of life in a diverse and vulnerable patient population. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2022;33(4):1793-1808. doi:10.1353/hpu.2022.0138

5. Zhang J, Sulistio M, Alvarez K, et al. Epic-Fail: ICD education through a patient portal in highly diverse, safety-net population. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2025;69(5):e424-e425. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2025.02.030