Concomitant Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation With Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement: Effective, Evolving, and Underutilized

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2025;25(11):12-17.

Panos N Vardas, MD1; Omar Mahmud2; Ioannis Liapis, MD3; and Marvi Tariq, MD1

1Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama; 2Medical Student, Medical College, The Aga Khan University, Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan; 3Department of Surgery, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama

Overview

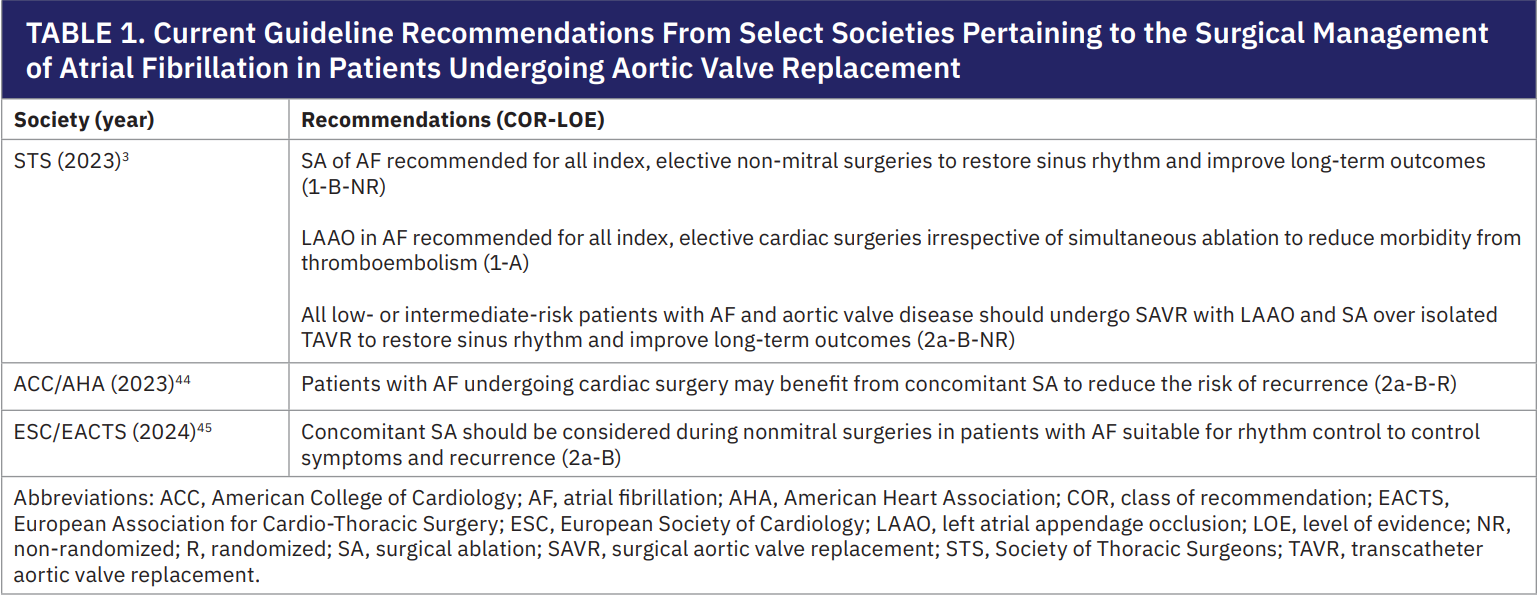

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia, affecting an estimated 30% to 50% of patients undergoing aortic valve replacement (AVR).1-3 AF is a treatable driver of reduced survival and quality of life (QoL) due to palpitations, heart failure, and stroke.1,4-6 Standard management relies on rate control and anticoagulation, but patients undergoing cardiac surgery present a unique opportunity to definitively treat AF with concomitant surgical ablation (SA) and left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO). Strong evidence indicates that this combined approach is the most effective and durable treatment for AF, yet only a minority of surgeons routinely perform concomitant AF surgery.7-10 To reflect this, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) issued a class I recommendation in its 2023 guidelines to add SA and LAAO during all index, elective cardiac operations (mitral and nonmitral). The guidelines also include a class IIa recommendation favoring surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) with concomitant AF treatment over transcatheter AVR (TAVR) in patients with AF (Table 1).3 In this article, we highlight how SA and LAAO can be safely and efficiently incorporated into SAVR to optimize patient outcomes.

Mechanistic and Technical Considerations

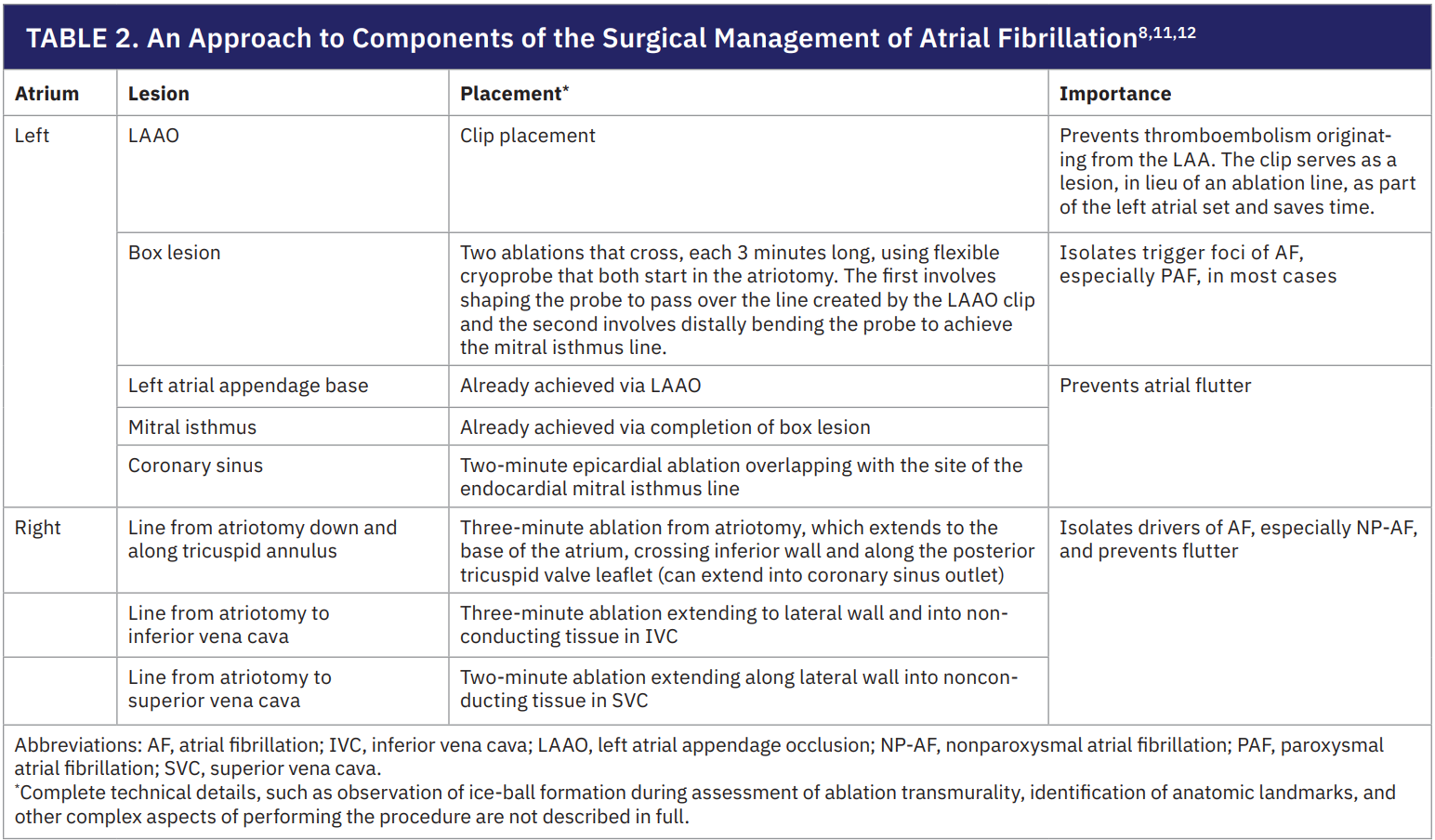

Surgeons classify AF as paroxysmal (PAF) and nonparoxysmal (NP-AF) based on its pathophysiology and responsiveness to treatment. PAF is usually triggered by foci in the pulmonary veins (PVs) or posterior left atrium (LA), and it can often be controlled by electrically isolating that region (a “box lesion”). However, NP-AF is sustained by broader atrial substrates or “drivers” and usually requires a more extensive Cox-Maze IV lesion set to disrupt. Understanding these mechanisms guides the ablation strategy during SAVR.

Effective treatment of AF during SAVR rests on the following key principles:

- Prioritizing the valve surgery. Safe AVR should remain the primary goal, and the heart should be carefully assessed (tissue integrity, aortic root anatomy, etc). The surgeon should be willing to modify the SA if needed to ensure a successful and safe AVR.

- Strategically placing lesions. Place transmural ablations where they start and end on nonconductive structures (eg, existing atriotomy suture lines or the LAAO clip), in the event a Cox-Maze procedure is performed. This leverages surgical incisions and clips to minimize the number and duration of ablations required.11

- Using cryoablation for efficiency and safety. Flexible cryoprobes reliably create transmural lesions with 2-3 minutes of application (thin versus thick tissue, respectively), typically adding less than 15 minutes of cardiopulmonary bypass time.11 The probe can be shaped to complete multiple lines at once (for example, simultaneously finishing the box lesion and mitral isthmus line) and can be safely reapplied to ensure lesion completeness without risking tissue injury or perforation.11

- Tailoring the lesion set to the patient. Each lesion in the SA procedure should have a clear purpose (Table 2) and its benefit must outweigh the cost of added bypass time or permanent pacemaker (PPM) risk.8,12 In practice, lesion sets can be adjusted based on patient factors to balance efficacy and safety.

Underutilization of Concomitant Surgery With AVR

Given the prevalence and consequences of AF in AVR patients, effectively treating the rhythm disturbance, and not just the diseased valve, is critical for optimal outcomes.1 Nevertheless, concomitant AF surgery remains underutilized and only about 30% of eligible patients receive AF treatment during SAVR.3,13 Surveys of cardiac surgeons suggest that many overestimate the risk of adding SA, fearing complications such as cardiac perforation, or PPM at rates far higher than those actually observed.14,15 This gap between perceived and real risk has led to a hesitancy to surgically ablate AF and underscores the need to reiterate the excellent safety and efficacy profile of concomitant SA and LAAO.

Safety of Concomitant Surgery for AF

Multiple studies, including risk-adjusted and propensity-matched analyses, have found that adding SA and LAAO to ‘closed’ atrium operations (such as SAVR or CABG) does not increase operative morbidity or mortality; in fact, some studies suggest it can even improve outcomes.1,2,5,16-18 Although LAAO alone is widely accepted to be safe, surgeons often cite the risks of SA, chiefly renal complications and PPM, as deterrents.3,19,20 However, the observed renal issues in the literature have been mostly transient acute kidney injuries rather than permanent or severe renal failure, and do not negate the long-term benefits of treating AF.21

The incidence of new PPMs after concomitant SA is also lower than what many assume. In the CTSN randomized trial, about 10% of patients who underwent SA needed a PPM at 1 month, but other studies have reported lower rates.20,22 Importantly, when PPMs are required after AF surgery, it is often for pre-existing conduction system disease, such as heart block or sick sinus syndrome (SSS), rather than due to direct injury from ablation. Surgical lesions avoid the atrioventricular node, making ablation-induced heart block unlikely, and SSS may simply be unmasked by restoring sinus rhythm in patients with long-standing AF.8 Yet, PPM placement is a significant event associated with worse long-term survival, and minimizing its occurrence is crucial.23 Fortunately, techniques to reduce PPM risk have been described and validated.11,12 These approaches emphasize balancing the completeness of lesion sets against the potential for complications. One proposed risk-benefit hierarchy for tailoring lesion sets during AF surgery is as follows:12

- LAAO for all. Performance of LAAO in every patient as it carries almost no risk, prevents stroke, and counts as an ablation line (the clipped appendage serves as an electrical barrier).

- LA ablation lines or completion of “box lesion set” as needed. Complete the LA lesion set (beyond the appendage) in most cases, as these are necessary to eliminate AF triggers and circuits in the majority of patients. However, extensive LA ablation adds cross-clamp time and can be challenging in friable tissue. Commercially available clamps can provide radiofrequency-mediated epicardial transmural ablation for the “box lesion set” without the need to perform an intracardiac procedure.

- Right atrial (RA) lines in select cases. Use RA lesions only for patients with substantial RA enlargement or very long-standing AF, where biatrial involvement is likely.

This tailored strategy remains under investigation, as some experts advocate for biatrial lesion sets in all cases to maximize efficacy.8 Overall, the risk of needing a pacemaker after concomitant AF surgery is not high and can be managed with careful technique. Additionally, concerns about atrial perforation or excessive tissue trauma are not borne out in clinical series and flexible cryoprobes allow lesions to be created without structural damage. In appropriate candidates, surgeons should not withhold SA during SAVR out of an unfounded fear of complications.

Efficacy of Concomitant Surgery for AF

With safety established, substantial evidence supports the efficacy of treating AF during SAVR. First, randomized trials in patients undergoing mitral valve surgery have demonstrated that adding surgical ablation yields high rates of durable sinus rhythm, and long-term follow-up from the PRAGUE-12 study even showed a reduction in stroke.2,13,24-30

Second, trials in other clinical scenarios have found that actively managing AF (with catheter ablation or aggressive rhythm control) improves major outcomes, including survival, especially in patients with heart failure or significant AF symptoms.31-33 These contexts are not directly comparable to surgery, but reinforce the concept that sinus rhythm restoration benefits patients. Consistently, studies have shown that SA appears to be equally effective whether performed as a standalone procedure or alongside SAVR, with outcomes comparable or even superior to those seen in the mitral valve population.2,13 Many patients undergoing SAVR have impaired ventricular function or complex pathology, so they stand to gain significantly from eliminating AF. Finally, LAAO works synergistically with ablation by removing the primary source of thromboembolism and reducing stroke in cardiac surgery patients, as confirmed by the LAAOS III trial.20 Thus, SA and LAAO directly target the 2 main contributors to AF-related mortality (arrhythmia burden and stroke risk), making it plausible that their inclusion with SAVR improves long-term outcomes.34,35

Observational data align with this hypothesis. Multiple robust studies have reported that treating AF during cardiac surgery, including SAVR, is associated with higher freedom from AF, reduced need for anticoagulation, increased use of bioprosthetic valves, better QoL, and improved survival.1,2,5,17,19,36,37 The authors of the current STS guidelines performed a pooled analysis of long-term survival after SA versus no SA with cardiac surgery, and found a 23% decrease in risk of death.3 Similarly, a recent matched and adjusted analysis of over 10,000 Taiwanese patients who underwent SAVR found that those who received concomitant ablation had an 18% lower risk of death compared to those who had not.5 Taken together, SA and LAAO are thus very likely to enhance clinical outcomes for patients undergoing SAVR.

The Case for SAVR Over TAVR in Patients With AF

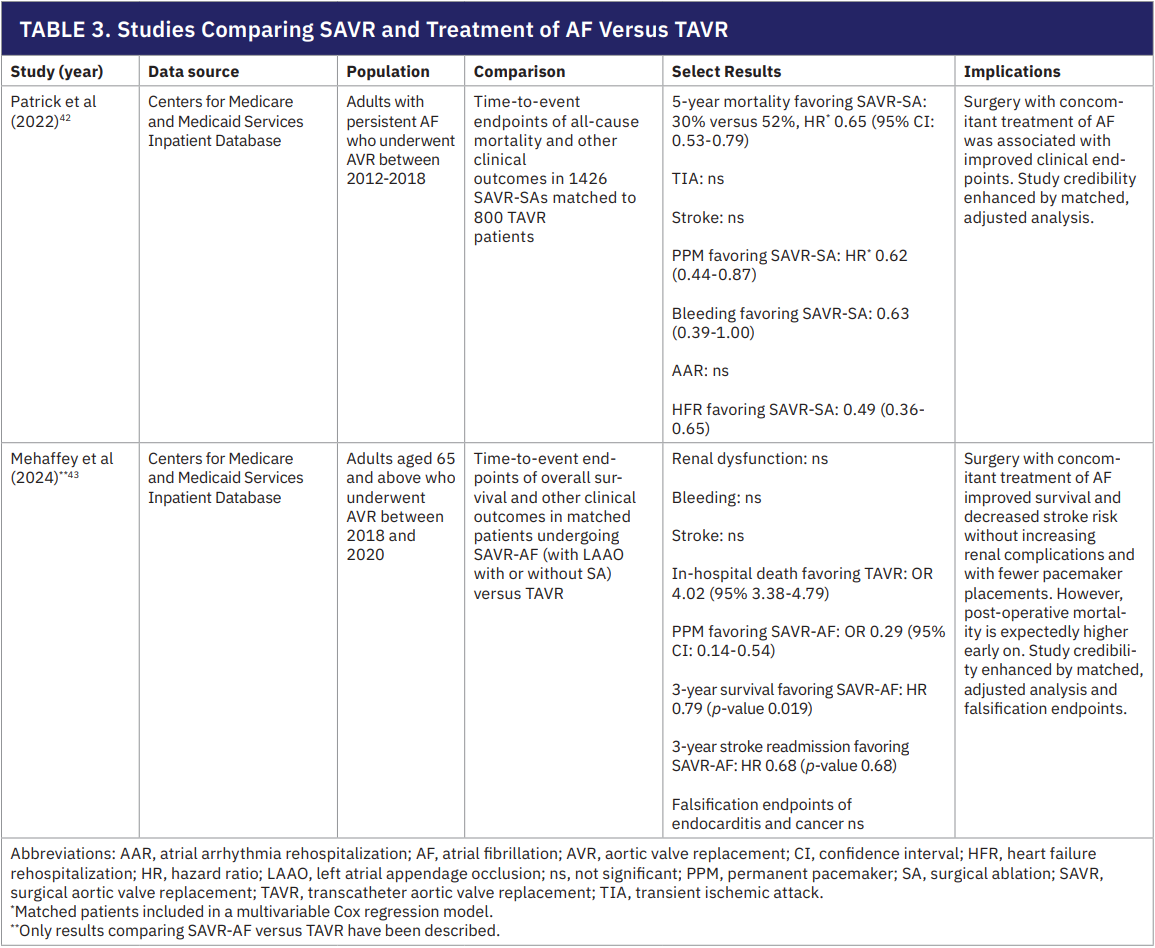

In recent years, TAVR has become increasingly common, often supplanting SAVR even in lower-risk patients. However, pre-existing AF is a well-known predictor of worse outcomes after TAVR, and only open surgery allows concomitant SA and LAAO.39-41 Recognizing this, a matched cohort study by Patrick et al (2022) compared over 2000 patients with persistent AF who underwent AVR and found that those who underwent SAVR with concomitant AF treatment (SAVR-AF) had 22% lower mortality at 5 years versus those who underwent TAVR.

Surgical patients also had fewer PPM implants, less bleeding, and fewer heart failure readmissions.42 Stroke rates were similar between groups. Likewise, Mehaffey et al (2024) reported an analysis of SAVR-AF versus TAVR in Medicare patients and found a 21% reduction in long-term mortality and a 32% reduction in stroke-related hospitalizations favoring the surgical group, along with a dramatically lower rate of new pacemakers (odds ratio ~0.3) and no increase in renal complications.43 Given this evidence (Table 3), recent STS guidelines for the surgical treatment of AF classify as a IIa recommendation the combined approach of SAVR with SA and LAAO over isolated TAVR to restore sinus rhythm and improve long-term outcomes.3

Conclusions and Future Considerations

The greatest challenge in surgical AF management today is simply getting surgeons to use it. Uptake remains low, but the strengthened recommendations in recent guidelines (such as the STS 2023 class I endorsement of SA during concomitant cardiac surgery) and accumulating evidence of improved long-term outcomes should spur wider adoption of SA and LAAO during SAVR. This aligns with a modern vision of open heart surgery as a comprehensive intervention that can simultaneously address coronary artery disease, valve pathology, and arrhythmias in complex patients for whom medical or transcatheter options are suboptimal. In appropriately selected patients, adding SA and LAAO to SAVR is safe and necessary for the complete treatment of their cardiovascular disease.

Disclosures: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and have no disclosures to report. Dr Vardas reports honoraria from Medtronic for lectures, educational events, and support from Artivion for attending meetings and/or travel.

References

- Lee R, McCarthy PM, Wang EC, et al. Midterm survival in patients treated for atrial fibrillation: a propensity-matched comparison to patients without a history of atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(6):1341-1351. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.02.006

- Kowalewski M, Dąbrowski EJ, Kurasz A, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation with concomitant cardiac surgery: a state-of-the-art review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;67(7):ezaf187. doi:10.1093/EJCTS/EZAF187

- Wyler von Ballmoos MC, Hui DS, Mehaffey JH, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2023 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;118(2):291-310. doi:10.1016/J.ATHORACSUR.2024.01.007

- Malaisrie SC, McCarthy PM, Kruse J, et al. Burden of preoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(6):2358-2367.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.01.069

- Cheng YT, Huang YT, Tu HT, et al. Long-term outcomes of concomitant surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2023;116(2):297-305. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2022.09.036

- Quader MA, McCarthy PM, Gillinov AM, et al. Does preoperative atrial fibrillation reduce survival after coronary artery bypass grafting? Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(5):1514-1524. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.069

- Khiabani AJ, MacGregor RM, Bakir NH, et al. The long-term outcomes and durability of the Cox-Maze IV procedure for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;163(2):629-641.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.04.100

- McGilvray MMO, Barron L, Yates TAE, Zemlin CW, Damiano RJ. The Cox-Maze procedure: what lesions and why. JTCVS Tech. 2023;17:84-93. doi:10.1016/j.xjtc.2022.11.009

- Kearney K, Stephenson R, Phan K, et al. A systematic review of surgical ablation versus catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;3(1):159-129. doi:10.3978/J.ISSN.2225-319X.2014.01.03

- Huang H, Wang Q, Xu J, Wu Y, Xu C. Comparison of catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;163(3):980-993. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.04.154

- McCarthy PM. Simple but effective modifications to the Cox Maze procedure using only cryoablation. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024;29(2):134-148. doi:10.1053/j.optechstcvs.2023.05.006

- McCarthy PM. The Maze IV operation is not always the best choice: matching the procedure to the patient. JTCVS Tech. 2023;17:79-83. doi:10.1016/j.xjtc.2021.06.031

- Henn MC, Lawrance CP, Sinn LA, et al. Effectiveness of surgical ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation and aortic valve disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(4):1253-1260. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.04.016

- Mehaffey JH, Charles EJ, Berens M, et al. Barriers to atrial fibrillation ablation during mitral valve surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;165(2):650-658.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.03.039

- Belley-Cote EP, Singal RK, McClure G, et al. Perspective and practice of surgical atrial fibrillation ablation: an international survey of cardiac surgeons. Europace. 2019;21(3):445-450. doi:10.1093/EUROPACE/EUY212

- Ad N, Henry L, Hunt S, Holmes SD. Do we increase the operative risk by adding the Cox Maze III procedure to aortic valve replacement and coronary artery bypass surgery? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(4):936-944. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.12.018

- Yoo JS, Kim JB, Ro SK, et al. Impact of concomitant surgical atrial fibrillation ablation in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. Circ J. 2014;78(6):1364-1371. doi:10.1253/CIRCJ.CJ-13-1533

- Al-Atassi T, Kimmaliardjuk DM, Dagenais C, et al. Should we ablate atrial fibrillation during coronary artery bypass grafting and aortic valve replacement? Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(2):515-522. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.11.081

- Sakurai Y, Kuno T, Yokoyama Y, et al. Late survival benefits of concomitant surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation during cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiol. 2025;235:16-29. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2024.10.008

- Whitlock RP, Belley-Cote EP, Paparella D, et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion during cardiac surgery to prevent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(22):2081-2091. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2101897

- Bakir NH, Khiabani AJ, MacGregor RM, et al. Concomitant surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation is associated with increased risk of acute kidney injury but improved late survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;164(6):1847-1857.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.01.023

- Badhwar V, Rankin JS, Ad N, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation in the United States: trends and propensity matched outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(2):493-500. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.05.016

- DeRose JJ, Mancini DM, Chang HL, et al. Pacemaker implantation after mitral valve surgery with atrial fibrillation ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(19):2427-2435. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.062

- Doukas G, Samani NJ, Alexiou C, et al. Left atrial radiofrequency ablation during mitral valve surgery for continuous atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(18):2323-2329. doi:10.1001/JAMA.294.18.2323

- Gillinov AM, Gelijns AC, Parides MK, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation during mitral-valve surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1399-1409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1500528

- Osmancik P, Budera P, Talavera D, et al. Five-year outcomes in cardiac surgery patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing concomitant surgical ablation versus no ablation. The long-term follow-up of the PRAGUE-12 Study. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(9):1334-1340. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.05.001

- Abreu Filho CAC, Lisboa LAF, Dallan LAO, et al. Effectiveness of the maze procedure using cooled-tip radiofrequency ablation in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation and rheumatic mitral valve disease. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):120-125. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526301

- Blomström-Lundqvist C, Johansson B, Berglin E, et al. A randomized double-blind study of epicardial left atrial cryoablation for permanent atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing mitral valve surgery: the SWEDish Multicentre Atrial Fibrillation study (SWEDMAF). Eur Heart J. 2007;28(23):2902-2908. doi:10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHM378

- Chevalier P, Leizorovicz A, Maureira P, et al. Left atrial radiofrequency ablation during mitral valve surgery: a prospective randomized multicentre study (SAFIR). Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;102(11):769-775. doi:10.1016/J.ACVD.2009.08.010

- Sharples LD, Mills C, Chiu Y Da, et al. Five-year results of Amaze: a randomized controlled trial of adjunct surgery for atrial fibrillation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022;62(5):181. doi:10.1093/EJCTS/EZAC181

- Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, et al. Early rhythm-control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1305-1316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2019422

- AlTurki A, Proietti R, Dawas A, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19(1):1-13. doi:10.1186/S12872-019-0998-2/TABLES/5

- Packer DL, Piccini JP, Monahan KH, et al. Ablation versus drug therapy for atrial fibrillation in heart failure: results from the CABANA trial. Circulation. 2021;143(14):1377-1390. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050991

- Marijon E, Le Heuzey JY, Connolly S, et al. Causes of death and influencing factors in patients with atrial fibrillation: a competing-risk analysis from the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy study. Circulation. 2013;128(20):2192-2201. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000491

- Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98(10):946-952. doi:10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946

- Malaisrie SC, Lee R, Kruse J, et al. Atrial fibrillation ablation in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. J Heart Valve Dis. 2012;21(3):350-357.

- Musharbash FN, Schill MR, Sinn LA, et al. Performance of the Cox-maze IV procedure is associated with improved long-term survival in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(1):159-170. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.09.095

- Suwalski P, Kowalewski M, Jasiński M, et al. Survival after surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation in mitral valve surgery: analysis from the Polish National Registry of Cardiac Surgery Procedures (KROK). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157(3):1007-1018.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.07.099

- Maan A, Heist EK, Passeri J, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on outcomes in patients who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(2):220-226. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.027

- Yankelson L, Steinvil A, Gershovitz L, et al. Atrial fibrillation, stroke, and mortality rates after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(12):1861-1866. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.025

- Chopard R, Teiger E, Meneveau N, et al. Baseline characteristics and prognostic implications of pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: results from the FRANCE-2 Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1346-1355. doi:10.1016/J.JCIN.2015.06.010

- Patrick WL, Chen Z, Han JJ, et al. Patients with atrial fibrillation benefit from SAVR with surgical ablation compared to TAVR alone. Cardiol Ther. 2022;11(2):283-296. doi:10.1007/S40119-022-00262-w

- Mehaffey JH, Kawsara M, Jagadeesan V, et al. Atrial fibrillation management during surgical vs transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;118(2):421-428. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2024.03.020

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149(1):E1-E156. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

- Van Gelder IC, Kotecha D, Rienstra M, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): developed by the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Endorsed by the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Eur Heart J. 2024;45(36):3314-3414. doi:10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHAE176