View From the Left Ventricular Summit: Endocardial Ablation of Premature Ventricular Complexes Utilizing an Anatomic Approach

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2025;25(10):18-19.

Ibragim Al-Seykal, MD1; Tobias Ahnert2; Ankit Maheshwari, MD1

1Pennsylvania State University Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, Pennsylvania;

2Noorda College of Osteopathic Medicine, Provo, Uta

The left ventricular summit (LVS) is the highest point of the left ventricle when the heart is oriented in its attitudinal position. It is a common source of idiopathic premature ventricular complexes (PVCs). Ablation of PVCs originating from the LVS is challenging due to proximity of coronary vessels and presence of epicardial fat pads.1 We describe a case of successful LVS PVC ablation.

Case Presentation

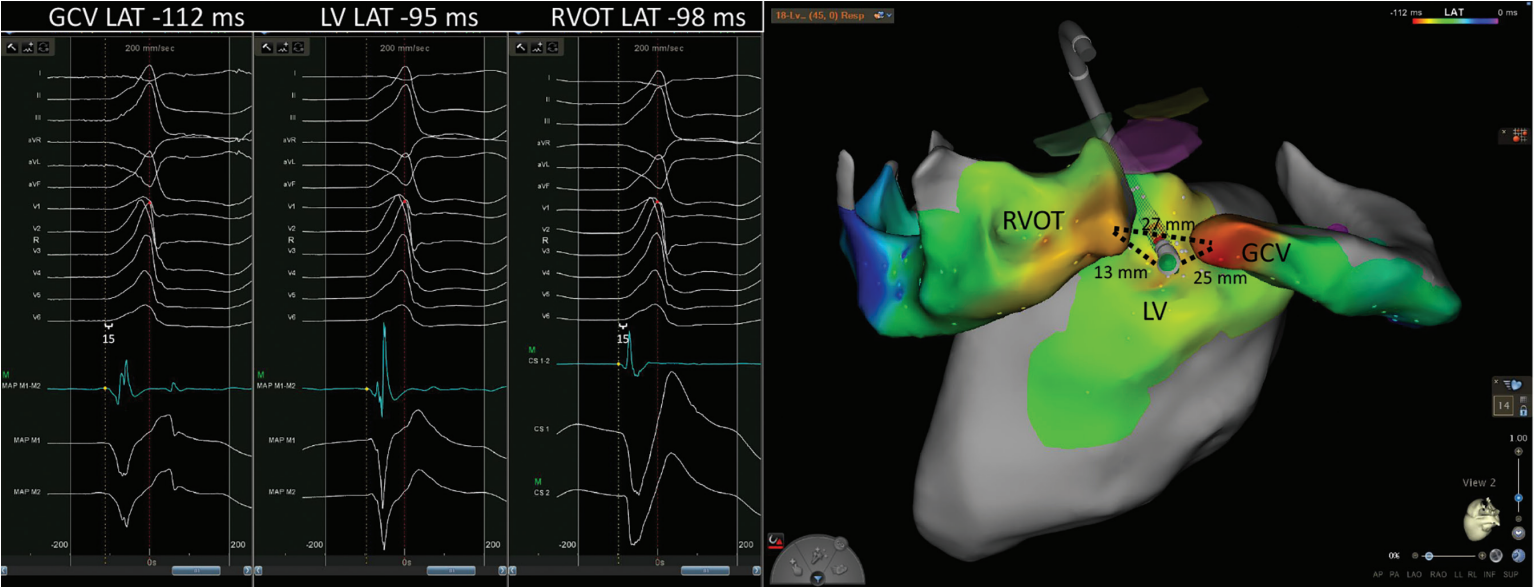

A 62-year-old man with coronary artery disease, bypass grafting, and preserved left ventricular function presented for ablation of a high burden (32%) of symptomatic premature ventricular complexes (PVCs). A detailed map of the coronary sinus, great cardiac vein (GCV), right and left coronary cusps, LV endocardium, and right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) was created using the Carto electroanatomic mapping system and the Decanav and QDOT Micro catheters (Johnson & Johnson MedTech). PVCs with a >95% match on the Carto Paso module to the clinical PVC were mapped (Figure). Local activation time (LAT) was manually annotated to the first rapid deflection of the bipolar electrogram from baseline. The earliest LAT relative to the Carto system’s automatic reference (red dot/dashed line) was noted in the GCV. A total of 138 seconds of ablation was performed from the GCV with an average of 14 to 20 watts per lesion in temperature control mode using the QDOT Micro catheter, but durable suppression was not achieved. It was noted that subtle changes in QRS morphology of mapped PVCs resulted in shifts of the Carto system’s automatic reference. When manually adjusting the reference to QRS onset, the earliest bipolar signals (15 ms pre-QRS) were found within the GCV and the posterior RVOT (white calipers). The earliest bipolar signal from the LV endocardium was on time with the initiation of the PVC. Based on this pattern of activation, an intramural or epicardial focus was suspected. Durable suppression of PVCs was achieved by ablation from the LV endocardium with the force vector directed between the earliest points from RVOT and GCV (Figure 1). The longest lesion was delivered at 40 watts for 157 seconds. The patient maintained resolution of symptoms at his 3-month follow-up visit and no PVCs were detected on his electrocardiogram.

Discussion

Annotating PVC LAT to the first rapid deflection of the bipolar electrogram can generate activation maps that facilitate effective catheter ablation. Successful ablation sites using this method of annotation have been previously described to have a median (interquartile range) pre-QRS time of 20.5 ms (17.8-26.0 ms) and 14 ms (11.2-22.6 ms) for immediate and delayed suppression, respectively. Failure was reported with a median (interquartile range) pre-QRS time of -3.5 ms (-9.2, 1.5 ms).2 For deep intramural foci often found with LVS PVCs, mapping ventricular signals from adjacent anatomic structures can facilitate triangulation of origin and allow for successful ablation from sites on the endocardium where local electrograms are not early relative to the onset of the QRS complex. This so-called anatomic approach has garnered more support in recent years. Longer lesions (2-3 minutes) and targeting sources <13 mm away from the endocardium have been associated with successful ablation.3,4

Summary

Arrhythmias originating from the LVS present unique challenges for catheter ablation. However, successful endocardial ablation can be achieved through appreciation and understanding of the complex anatomy of this region.

Funding: No internal or external funding was used for this manuscript.

Disclosure: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Ibragim Al-Seykal, MD, and Ankit Maheshwari, MD, have no disclosures to report. Tobias Ahnert reports he was employed by Johnson & Johnson MedTech until June 2025 and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson MedTech.

References

1. Das SK, Hawson J, Koh Y, et al. Left ventricular summit arrhythmias: state-of-the-art review of anatomy, mapping, and ablation strategies. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2024;10(11):2516-2539. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2024.09.008

2. Higuchi K, Yavin HD, Sroubek J, Younis A, Zilberman I, Anter E. How to use bipolar and unipolar electrograms for selecting successful ablation sites of ventricular premature contractions. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19(7):1067-1073. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2021.12.035

3. Peters CJ, Marchlinski FE. Left ventricular summit arrhythmias: have we reached the peak of ablation success or just a higher plateau? Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2024;17(5):e012969. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.124.012969

4. Yamada T, Kay GN. Trends favoring an anatomical approach to radiofrequency catheter ablation of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from the left ventricular summit. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2024;17(5):E012548. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.123.012548