Fall Mitigation After Implementing a Polypharmacy Reduction Program: An Observational Study

Abstract

This article evaluates the effectiveness of polypharmacy reduction programs in nursing homes as a quality improvement strategy for fall reduction in adults aged 65 or older. Reducing falls, which are common in this population, can improve quality of life and reduce liability risk. The polypharmacy reduction was achieved through best practices in managing hypertension, diabetes, psychiatric conditions, as-needed medications, and end-stage renal disease. Data collected 6 months before and after implementation showed a significant reduction in prescriptions, from a mean of 13.3 to 9.7 per patient (P<.05). Fall rates also decreased significantly, from 14.5 to 4.4 falls per month (P<.001), representing a 70% reduction. The study concludes that polypharmacy reduction is associated with a sustained decrease in both medication use and patient falls.

Citation: Ann Longterm Care. 2025. Published online May 1, 2025.

DOI:10.25270/altc.2025.11.001

Polypharmacy is common among older adults, with a prevalence estimated at 45.1% in adults aged 65 years or older.1 Reducing falls, which are common in this population, can improve quality of life and reduce liability risk.

Our study, conducted at a nursing home in Hyattsville, MD, was designed to determine whether fall rates would decrease in association with a polypharmacy reduction initiative. Medication usage and fall rates were measured before and during the program’s implementation. Polypharmacy reduction was accomplished using established best practices in the treatment of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, psychiatric conditions, as-needed (PRN) medications, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

All providers involved were provided monthly feedback regarding ongoing polypharmacy management. Fall data were collected monthly. The polypharmacy reduction program decreased medication use from a mean of 13.3 prescriptions per patient to 9.7 prescriptions per patient (P<.05). Patient falls also decreased from 14.5 before the medication reduction program to 4.4 falls per month (P<0.001). We observed that implementation of a polypharmacy reduction program significantly reduced prescriptions per patient on a sustained basis and coincided with a significant decrease in patient falls.

Methods

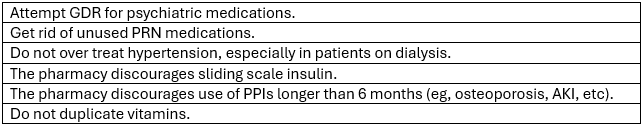

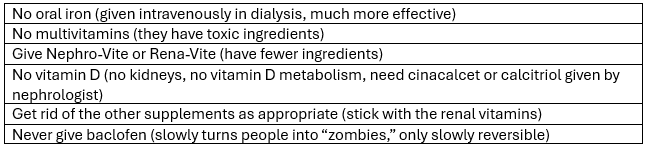

Three physicians and 3 nurse practitioners provided medical oversight for the residents for the 6 months before the polypharmacy reduction program and for the following 6 months during the program’s implementation. Each provider received monthly feedback regarding the current polypharmacy in their practice. Providers were encouraged to address gradual dose reduction (GDR) of psychiatric medications, liberalization of blood pressure control, liberalization of diabetes control, reduced use of PRN medications, and appropriate prescribing among patients with ESRD. Specific education was provided about appropriate prescribing practices in the geriatric population (Table 1) and in patients with dialysis-dependent ESRD (Table 2). Pharmacy consultants were not made aware of deprescribing by providers; they performed monthly reviews of patients’ medication at the facility but did not participate directly in this project, nor did the nursing staff.

Table 1. Guidance Given to Providers for Polypharmacy Reduction

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; GDR, gradual dose reduction; PPI, protein pump inhibitor; PRN, as needed.

Table 2. Guidance Given to for Providers for Patients With ESRD

Polypharmacy metrics were provided monthly to the providers. The scribe team provided the analysis to all facility providers. Data from the program were shared with nursing at weekly risk meetings and monthly Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings.

Results

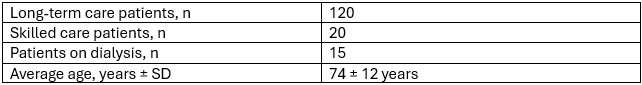

Demographics

The facility cares for an older adult population with a mixed payor source and a considerable proportion of patients with ESRD. See Table 3 for average age and distribution of patients between skilled and long-term care beds.

Table 3. Demographics of Patients at Study Nursing Home (N=140)

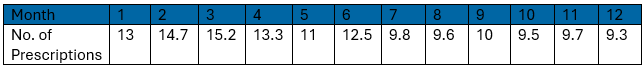

Polypharmacy

See Table 4 for measured total pharmaceutical prescriptions per patient. Between January and June prior to the implementation of the polypharmacy reduction program, the mean number of prescriptions per patient was 13.3 (SD, 1.53). After initiation of the polypharmacy reduction program from July to December, medication use fell to 9.7 prescriptions per patient (SD, 0.27). The calculated P value is less than .05, indicating the intervention created a statistically significant drop in prescriptions per patient.

Table 4. Pharmaceutical Prescriptions Per Patient

Falls

From January to June before the polypharmacy reduction program, the mean number of falls was 14.3 (SD, 5.15; see Table 5). After initiation of the polypharmacy reduction program, from July through December, the mean number of falls decreased to 4.5 (SD, 2.59). The P value is less than .001 indicating a highly significant difference between the observation and study months.

Table 5. Total Patient Falls Per Month

![]()

Discussion

Polypharmacy presents an opportunity for quality improvement in skilled nursing facilities. There are several specific areas where medication reduction might be expected to yield health benefits for the geriatric population.

Deprescribing is the process of tapering, stopping, discontinuing, or withdrawing drugs, with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes.2 A stepwise approach to deprescribing, starting with the most potentially inappropriate medications, can be used to gradually reduce polypharmacy.3

Polypharmacy reduction can come from implementing clinical practice guidelines that can help health care professionals make evidence-based decisions about medication management.4 These guidelines should be tailored to the specific needs of older adults in nursing homes and should consider factors such as frailty, cognitive impairment, goals of care, and life expectancy.5

Although nursing home staff were not included in this study, their education and training on medication management and polypharmacy reduction has been identified as a practical tool. Enhancing the knowledge and skills of nursing home staff can lead to improved medication practices and reduced polypharmacy,6,7 particularly in the geriatric management of diabetes, hypertension, psychiatric diseases, and the use of PRN drugs.

Traditional glycemic control goals, such as an A1C level of less than 7%, are not appropriate for all older adults.8,9 Older adults are more likely to experience side effects from medications used to control blood sugar, such as hypoglycemia, and may not benefit from tight glycemic control in terms of reducing the risk of complications such as heart disease and stroke.10 There is no evidence that tight glycemic control in older adults with diabetes reduces the risk of cardiovascular events or mortality.11 The risks of hypoglycemia and other adverse effects of tight glycemic control in older adults outweigh the potential benefits.12 Tight glycemic control in older adults with diabetes is associated with an increased risk of falls.13 In addition, falls are very common in older adults patients with ESRD, for which the most common cause in the United States is diabetes.14 Higher risk and prevalence of falls are seen in patients on hemodialysis, who also have greater diabetic complications, such as peripheral neuropathy and decreased visual acuity.14 Older adults with diabetes should be encouraged to focus on other important health goals, such as maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, and eating a healthy diet.

Traditional blood pressure (BP) control goals, such as a systolic BP of less than 140 mm Hg and a diastolic BP of less than 90 mm Hg, are not appropriate for all older adults. Older adults are more likely to experience side effects from medications used to control BP, such as dizziness, fatigue, and falls, and may not benefit from tight BP control in terms of reducing the risk of complications, such as heart disease and stroke.15,16 There is no evidence that tight BP control in older adults reduces the risk of cardiovascular events or mortality. The risks of side effects from BP medications and other adverse effects of tight BP control in older adults outweigh the potential benefits.17 Because tight BP control in older adults is associated with an increased risk of falls, those with hypertension should be encouraged to focus on other important health goals, such as maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, and eating a healthy diet.

GDR of psychiatric medications in nursing homes has been a topic of interest for researchers and health care providers, as it can reduce adverse effects and improve residents' quality of life. Tjia and colleagues18 found that nursing home residents with advanced dementia were often prescribed multiple medications, some of which may be unnecessary or potentially harmful. GDRs help reduce the use of these medications, potentially improving the residents’ quality of life and decreasing the risk of adverse effects, including orthostatic hypotension, arrythmias, blurred vision, sedation, urinary retention, infections, delirium, and even death.

Reducing the use of PRN medications has been suggested as a potential strategy to decrease the risk of falls in nursing home patients. Several studies have identified a relationship between the use of PRN medications, particularly sedatives and psychotropic drugs, and an increased risk of falls in nursing home residents.19,20 These medications can cause dizziness, sedation, and impaired cognitive function, which may increase the likelihood of falls.20 Interventions aimed at reducing the use of PRN medications in nursing homes have shown promise in reducing falls. A study by Fick and colleagues22 showed that a multicomponent intervention focused on decreasing the use of PRN medications and other risk factors led to a significant reduction in falls among nursing home residents.

Promoting shared decision-making between health care professionals, residents, and their families can encourage patient-centered care and improve medication management.23 Involving residents and their families in medication-related discussions helps ensure that their preferences and values are considered when making decisions about deprescribing or adjusting medication regimens.24

Our study focused on the relationship between polypharmacy reduction and fall. Falls in nursing homes are a significant concern, as they can lead to serious injuries and negatively impact residents' quality of life. The incidence of falls in nursing homes varies depending on such factors as residents' physical and cognitive conditions, staffing levels, and the facility's environment and fall prevention programs.25,26 Rubenstein and Josephson25 reported that the fall rate in nursing homes was approximately 1.5 falls per bed per year, which equates to about 0.125 falls per bed per month. Ambrose and colleagues26 found that about 50% of nursing home residents experienced falls, with a median fall rate of 2.6 falls per person per year. It is estimated that about 20% of fall in elderly patients cause a serious injury like fractures, traumatic brain injuries and death.27

Fall prevention in skilled nursing home environments is essential for ensuring the safety and well-being of elderly residents. It is generally accepted that a multifaceted approach to fall prevention in skilled nursing home environments should include individual risk assessment, environmental modifications, physical exercise programs, and staff education. Implementing these strategies has been shown to effectively reduce the risk of falls and improve resident safety.25,28

In this study, we implemented a feedback system of polypharmacy reduction. In addition to provide feedback, the polypharmacy program provided specific guidance for medication reduction opportunities including the geriatric management of diabetes, hypertension, psychiatric medications, as-needed medications, and prescribing for ESRD.

While many comprehensive strategies have been proposed for achieving polypharmacy reduction, this study demonstrated the efficacy of a polypharmacy reduction program built on monthly feedback and specific guidance to reduce prescriptions for diabetes, hypertension, GDR, ESRD, and PRN medications. A measurable potential benefit of such a program would be fall reduction. Combining all the modalities under the umbrella of polypharmacy reduction was associated with striking results. After polypharmacy reduction, the number of falls significantly decreased to 4.5 falls per month. Falls and potential patient harm were reduced.

Achieving and sustaining polypharmacy reduction was the goal of this quality improvement project. This result was achieved with clinical leadership oversight and data analysis. No outside funding was required. No additional nursing or facility support was required. Accordingly, this suggests that significant polypharmacy reduction is within the reach of many skilled nursing facilities with similarly diverse patient populations and provider backgrounds.

Limitations

By its nature, reducing polypharmacy cannot be subject to a double-blinded study. Additionally, since reducing polypharmacy is part of the standard of care, a control arm would not be ethical. Accordingly, this study carries the limitations of an observational study with its implied biases. It is also important to note that many factors other than polypharmacy can cause an increase in falls, such as the resident’s frailty, increase in short-term admissions, facility construction, staff turnover, and agency use.

Affiliations, Disclosures, & Correspondence

Authors: Thomas Masterson, MD, MS, CMD • Nader Tavakoli, MD, CMD, FAAFP • Ijeoma Josephine Nwogu, MD • Jonathan Nichols, BA • Reine Leutze, RN, BS • Karika Sethi, MS

Affiliations:

Department of Family Medicine, University of Maryland Capital Region Medical Center

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Nader Tavakoli, MD, CMD, FAAFP

Chair, Dept of Family Medicine

Professor of Family Medicine, Ross University and University School of Medicine (RUSM)

University of Maryland Capital Region Medical Center

901 Harry S Truman Drive Largo, MD 20774

References

- Wang X, Liu K, Shirai K, et al. Prevalence and trends of polypharmacy in U.S. adults, 1999-2018. Glob Health Res Policy. 2023;8(1):25. doi:10.1186/s41256-023-00311-4

- Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: what is it and what does the evidence tell us? Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66(3):201-202. doi:10.4212/cjhp.v66i3.1261

- Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1648-1654. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.355

- Steinman MA, Beizer JL, DuBeau CE, Laird RD, Lundebjerg NE, Mulhausen P. How to use the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria—A guide for patients, clinicians, health systems, and payors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;66(12):2255-2259. doi:10.1111/jgs.13701

- American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694. doi:10.1111/jgs.15767

- Crotty M, Whitehead C, Rowett D, et al. An outreach intervention to implement evidence-based practice in residential care: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN67855475]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):6. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-4-6

- Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, et al. An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomized controlled trial of case conferencing. Age Ageing. 2004;33(6):612-617. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh213

- Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al; ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2560-2572. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802987

- Reaven PD, Emanuele NV, Wiitala WL, et al; VADT Investigators. Intensive glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(23):2293-2303. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806802

- Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al; ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):1773-1786. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61303-8

- Gerstein HC, Miller M, Byington RP, et al; Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545-2559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802743

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Neil HAW, Matthews DR. 10-year follow-up of intensive blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2560-2569. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0806470

- DCCT/EDIC Study Group. Intensive glycemic control and risk of falls in older adults with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2550-2559.

- Abdel-Rahman E M, Turgut F, Turkmen K, Balogun R A. Falls in elderly hemodialysis patients. QJM. 2011;104(10):829-838. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcr108

- Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al; SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Blood Pressure Lowering Trialists' Collaboration. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;367(9386):1575-1585.

- Jamerson KL, Davis CE, Cutler JA, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure control in older diabetic patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(19):1883-1898.

- Tjia J, Rothman MR, Kiely DK, et al. Daily medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(5):880-888. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02829.x

- Ray WA, Taylor JA, Meador KG, et al. A randomized trial of a consultation service to reduce falls in nursing homes. JAMA. 1997;278(7):557- 562. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550070049037

- Hartikainen S, Lönnroos E, Louhivuori K. Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(10):1172-1181. doi:10.1093/gerona/62.10.1172

- Ayerbe L, Forgnone I, Foguet-Boreu Q, Gonzalez E, Addo J. The association between medication use and the risk of falling in older adults. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2021;10(1):1-10.

- Fick DM, Steis MR, Waller JL, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia is associated with prolonged length of stay and poor outcomes in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2013;12(9):684-689. doi:10.1002/jhm.2077

- Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, Valluri S, Briesacher BA. Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(5):285-307. doi:10.1007/s40266-013-0064-1

- Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793-807. doi:10.1007/s40266-013-0106-8

- Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR. Falls and their prevention in elderly people: what does the evidence show? Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(5):807-824. doi:10.1016/S0025-7125(02)00008-0.

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51-61. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.009

- Vaishya R, Vaish A. Falls in older adults are serious. Indian J Orthop. 2020;54(1):69-74. doi: 10.1007/s43465-019-00037-x

- Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD005465. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub3

References

- Wang X, Liu K, Shirai K, et al. Prevalence and trends of polypharmacy in U.S. adults, 1999-2018. Glob Health Res Policy. 2023;8(1):25. doi:10.1186/s41256-023-00311-4

- Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: what is it and what does the evidence tell us? Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66(3):201-202. doi:10.4212/cjhp.v66i3.1261

- Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1648-1654. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.355

- Steinman MA, Beizer JL, DuBeau CE, Laird RD, Lundebjerg NE, Mulhausen P. How to use the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria—A guide for patients, clinicians, health systems, and payors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;66(12):2255-2259. doi:10.1111/jgs.13701

- American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694. doi:10.1111/jgs.15767

- Crotty M, Whitehead C, Rowett D, et al. An outreach intervention to implement evidence-based practice in residential care: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN67855475]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):6. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-4-6

- Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, et al. An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomized controlled trial of case conferencing. Age Ageing. 2004;33(6):612-617. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh213

- Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al; ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2560-2572. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802987

- Reaven PD, Emanuele NV, Wiitala WL, et al; VADT Investigators. Intensive glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(23):2293-2303. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806802

- Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al; ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):1773-1786. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61303-8

- Gerstein HC, Miller M, Byington RP, et al; Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545-2559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802743

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Neil HAW, Matthews DR. 10-year follow-up of intensive blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2560-2569. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0806470

- DCCT/EDIC Study Group. Intensive glycemic control and risk of falls in older adults with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2550-2559.

- Abdel-Rahman E M, Turgut F, Turkmen K, Balogun R A. Falls in elderly hemodialysis patients. QJM. 2011;104(10):829-838. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcr108

- Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al; SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Blood Pressure Lowering Trialists' Collaboration. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;367(9386):1575-1585.

- Jamerson KL, Davis CE, Cutler JA, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure control in older diabetic patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(19):1883-1898.

- Tjia J, Rothman MR, Kiely DK, et al. Daily medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(5):880-888. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02829.x

- Ray WA, Taylor JA, Meador KG, et al. A randomized trial of a consultation service to reduce falls in nursing homes. JAMA. 1997;278(7):557- 562. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550070049037

- Hartikainen S, Lönnroos E, Louhivuori K. Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(10):1172-1181. doi:10.1093/gerona/62.10.1172

- Ayerbe L, Forgnone I, Foguet-Boreu Q, Gonzalez E, Addo J. The association between medication use and the risk of falling in older adults. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2021;10(1):1-10.

- Fick DM, Steis MR, Waller JL, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia is associated with prolonged length of stay and poor outcomes in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2013;12(9):684-689. doi:10.1002/jhm.2077

- Tjia J, Velten SJ, Parsons C, Valluri S, Briesacher BA. Studies to reduce unnecessary medication use in frail older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(5):285-307. doi:10.1007/s40266-013-0064-1

- Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793-807. doi:10.1007/s40266-013-0106-8

- Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR. Falls and their prevention in elderly people: what does the evidence show? Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(5):807-824. doi:10.1016/S0025-7125(02)00008-0.

- Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51-61. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.02.009

- Vaishya R, Vaish A. Falls in older adults are serious. Indian J Orthop. 2020;54(1):69-74. doi: 10.1007/s43465-019-00037-x

- Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD005465. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub3