Light Up Their Lives: Bringing Music to Patients With Dementia in Rural Tennessee

Abstract

Personalized music is an intervention that may be used with patients with dementia or Alzheimer disease (AD) to decrease corresponding negative behaviors. This pilot study evaluated the use of personalized music with patients with dementia and AD and measured the effectiveness of the intervention using the Multidimensional Observation Scale for Elderly Subjects (MOSES). Using a convenience sample of 47 patients with the diagnosis of dementia or AD, the researchers conducted the study in long-term care facilities in rural middle Tennessee. Results from this study align with others that support the benefits of regular music activities for patients’ emotional, cognitive, and social abilities. Additionally, training caregivers and health care staff to implement personalized music activities is a cost-effective way to stimulate and enrich the lives of patients with dementia or AD.

Citation: Ann Longterm Care. 2025. Published online July 22, 2025.

DOI:10.25270/altc.2025.11.002

Alzheimer disease (AD) is becoming a leading cause of death, affecting over 7 million people in the US.1 It was the seventh leading cause of death, contributing to 120 022 deaths in 2022.2 Of the 10 leading causes of mortality in the US, AD is the only one that cannot be prevented, cured, or alleviated after a confirmed diagnosis.3 AD is only one of many types of dementia; however, dementia (all types) affected over 57 million people in the world in 2021, with 10 million new diagnoses projected annually.4 Recognized as a public health priority by the World Health Organization, dementia care extends beyond patients with the disease to also support families and caregivers, who often experience significant emotional and psychological strain.4 Loss of memory and recognition are among the most burdensome facets of this disease.

Rural Connection to Alzheimer Disease

A meta-analysis by Russ and colleagues found a high prevalence of AD in rural communities, particularly among people who lived in rural settings early in their lives.5 However, the study’s conclusions were limited due to a lack of studies from resource-poor countries. Further efforts are needed to examine certain conditions (ie, heart issues; incidence of stroke) in specific geographic regions to identify potential causal connections and risk factors and explore potential social or environmental changes.

Rural Tennessee

This project focused on the implementation of a personalized music program for patients with AD and/or dementia in 5 nursing home facilities in Putnam, White, and Overton counties in the Upper Cumberland region of Tennessee. According to the US Census, the 2021 population of Tennessee was 6 975 218.6 Overton and White counties had a higher percentage of the population who were over the age of 65, a lower percentage of high school graduates aged 25 years or older for years 2016 to 2020, and a lower percentage of individuals with a bachelor’s degree or higher aged 25 years or older for 2016 to 2020. The selected counties are predominantly White (93.1%), compared with Tennessee (78.2%) and the US overall (75.8%). From 2016 to 2020, 10.1% to 11% of the population under the age of 65 in the selected counties had a disability compared with 8.7% nationally, and 12.1% to 13.3% of the population under age 65 lacked health insurance compared with 10.2% nationally. Economic data suggest that incomes are lower in Tennessee and the 3 selected counties, and the poverty rate is higher compared with the US overall.

Background of the Music & Memory Program

In 2010, social worker Dan Cohen introduced customized familiar music via an iPod to aging patients with AD and dementia, leading to the creation of the Music & Memory program to train others in this approach.7 Cohen’s evidence-based strategies, documented by Michael Rossato-Bennett in the video Alive Inside: A Story of Music and Memory, exemplified an innovative way to use music to improve patients’ ability to communicate and interact verbally and nonverbally with family members and health care staff.8

Research Outcomes for Patients With Dementia and Music Intervention

Implementation of music into dementia care can have many positive outcomes. Studies have supported that music may decrease the use of antipsychotic medications and decrease negative behaviors of dementia, including aggression and depression.9,10 Music therapy for patients with dementia may also improve physical safety, as research has shown it may reduce falls9,11 and improve the ability to swallow.12 In an intensive care study, patients who received music therapy experienced less delirium, as measured by the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU), compared with the control group.13

Research Goal

The goal of this study was to implement and evaluate the effectiveness of a personalized music intervention to improve the physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning of patients with AD or dementia, as measured by the Multidimensional Observation Scale for Elderly Subjects (MOSES).

Methods

The project, titled “Improvement of Quality of Life for Nursing Home Residents Through the ‘Music & Memory’ Program,” provided residents with personalized music through the use of MP3 players.14 Since AD and dementia impact a large proportion of residents in US and Tennessee nursing homes, the program aimed to enhance care in multiple nursing homes in the Upper Cumberland area of Tennessee. Through procurement of a state-funded Civil Money Penalty Quality Initiatives (CMPQI) grant, funds were obtained for program certification, supplies, and labor for each nursing home to become certified as a Music & Memory program.15

In addition to covering the cost of the certification, renewal fees, and program start-up, the grant provided MP3 players; a computer in each of the facilities dedicated to the project (music library); and other limited supplies that remained with the designated facility after the conclusion of the project. It also funded training for the agencies’ staff as well as for nursing students, faculty, nursing home staff, and families. Music & Memory certification training included 3 90-minute webinars that provided detailed instruction on the integration of digital music into the resident’s care plan and evaluation of its effectiveness.15 The university’s institutional review board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from each patient’s legal guardian before study enrollment. To measure the effectiveness of the program, the CMPQI grant used evidence-based practice to measure the residents’ cognitive and psychosocial functioning, as observed by their nursing home caregivers.

Nursing faculty served as co-investigators in implementing the Music & Memory program, but a unique aspect of the study was involving nursing students in addition to staff, caregivers, and family members. As nursing is a holistic, multidimensional profession that addresses a patient’s emotional, psychological, social, and physical needs, this project provided an opportunity for nursing students to transition from theoretical learning to real-world practice.

Most of the nursing students who helped implement the program were senior students in their last semester of nursing school, participating in their Leadership and Management or Community Health clinical rotations. Nursing students, faculty, and the health care and/or nursing team were able to implement the Music & Memory activities with the patients and then document their behaviors. The students helped with managing program start-up, teaching as needed, implementing the program, and assisting nonlicensed personnel, family, and other caregivers in implementing the project with the patients.

The method for selecting personalized music varied among residents. In many cases, investigators acted as “music detectives,” using guidance from Music & Memory to create playlists individualized to each resident’s formative years (ideally ages 10 to 25).16 Family members were consulted, as most residents were unable to recall their favorite music from this time. For some residents, playlists included a variety of genres with songs from that period of their lives, considering their cultural background and life experiences. Residents were observed closely during the first listening session. The goal was to develop an initial playlist for each resident containing at least 25 songs and then add or delete songs based on their responses.

The optimal frequency and duration of the music intervention were individualized for each resident based on their preference or response. For the purposes of the study, residents were asked to engage with the music intervention at least 3 times per week for 3 to 10 minutes per session.

Researchers aimed to improve the physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning of patients with AD/dementia, as measured by the MOSES, and specifically addressed the ability to “improve quality of life and care of residents through person-centered care,” according to the terms of focus under the CMPQI grant. Measures included observations by caregivers. The MOSES is a 40-item instrument for the caregiver to answer related to patients’ emotional well-being and activities of daily living.17 Studies have shown that the MOSES effectively differentiates across institutional settings, with internal consistency reliabilities reported in the 0.8 range, and interrater reliabilities reported between 0.58 and 0.97.17 Data analysis entailed comparing patient observations during different periods to identify any positive changes in desired outcomes from baseline; however, due to patient attrition, meaningful comparisons with the baseline were limited to data from the first through the eighth observation periods.

Results

Analysis of Data Obtained Using the Multidimensional Observation Scale

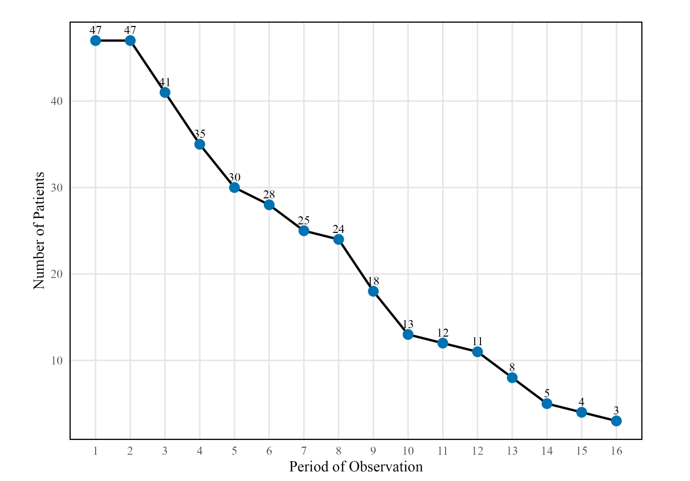

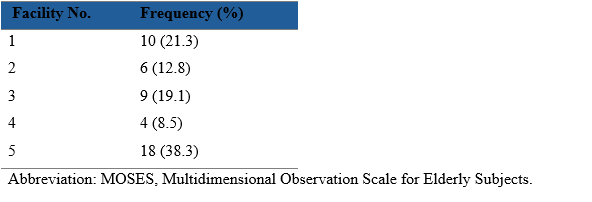

Data analyses included descriptive statistics and chi-square tests of equality of proportions. The Figure shows the number of patients who were observed during each period, up to 16 observation periods. It is important to note that all patients were observed during the same time; however, there was approximately a 2-week period between each observation. The number of observed patients constantly dropped over time, as shown in the Figure. The analysis involved calculating the differences in proportions between the eighth and first periods, as well as the differences in proportions between the fourth and first periods, for each item on the scale. During period 4, 35 patients were observed; during period 8, 24 patients were observed. All participants were observed at least twice. The patients were all located at different facilities (Table 1).

Figure. Number of Cases Observed During Each Period

Table 1. Patients by Facility: MOSES Data (N=47)

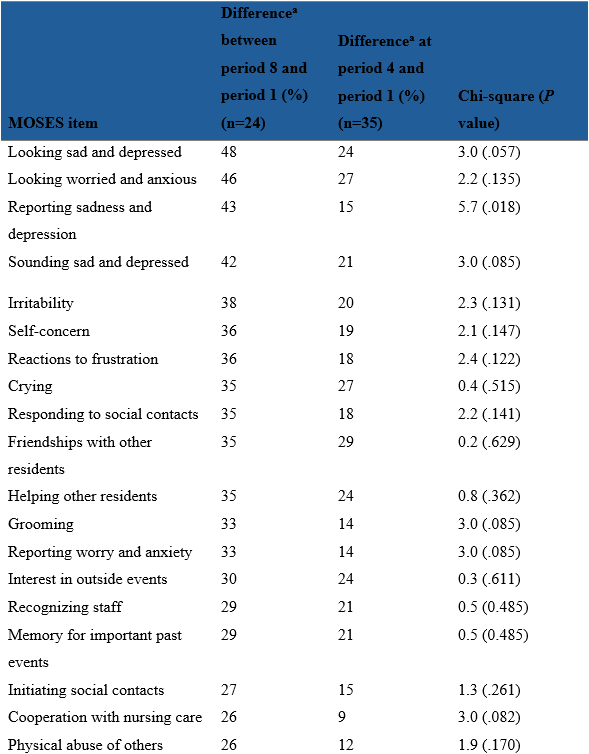

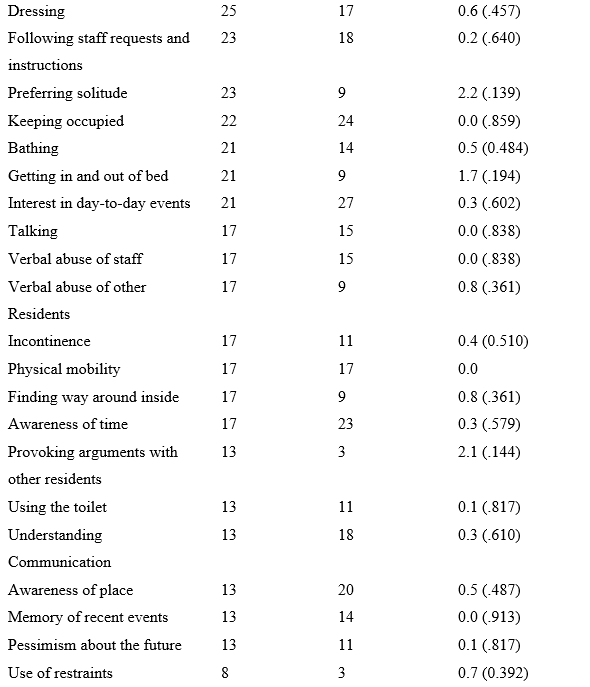

The program made a positive impact among the residents. Given the demographic of the population involved, the reported results seemed encouraging. Positive changes were noted across several items measured by MOSES. The largest positive changes were among the following items, all of which were related to feelings of depression and anxiety: looking sad and depressed (48%), looking worried and anxious (46%), reporting sadness and depression (43%), sounding sad and depressed (42%), and irritability (38%).The 5 items with the least reported positive changes were use of restraints (8%), using the toilet (13%), understanding communication (13%), memory of recent events (13%), pessimism about the future (13%), and provoking arguments with other residents (13%).

Table 2 shows differences between each item evaluated at periods 4 and 8 (sorted by period 8 percentages). The percentage of patients with positive changes increased with 4 additional intervention periods (and observation); however, the sample size was not consistent during the 2 periods used to evaluate this difference (see Table 2). Overall, findings suggest that a longer the implementation period of the Music & Memory program leads to better patient health outcomes.

Differences between the 2 percentages at periods 4 and 8 were tested using the chi-square test of equality of proportions. Significance was evaluated using an α level of 0.10 and adjusted for type I error using the Bonferroni correction. Thus, to be significant at the .10 α level, each P value would need to be less than or equal to .0025. A higher α level was chosen due to the exploratory nature of this study, particularly the need to detect potentially significant findings. In exploratory research, a higher risk of false positives is generally accepted in the pursuit of new investigative paths. While 5 items did not reach statistical significance, their observed differences were notable and warrant attention: looking sad and depressed, reporting sadness and depression, grooming, reporting worry and anxiety, and cooperation with nursing care.

Table 2. Period 8 and 4 Evaluation Percentages by MOSES Item

Abbreviation: MOSES, Multidimensional Observation Scale for Elderly Subjects.

aThe percentages reported are net differences. This indicates that there were increases in the percentage of participants reporting gains at both evaluation periods in this table.

Qualitative Observations

The following are qualitative observations from the field notes of the faculty investigators. These direct observations provide additional insights of responses to the music intervention.

- “In one facility, there was a married couple who both participated in the program—sometimes they would listen to music together and his cognition was pretty good. He could sing songs to her from their wedding and first dates. This made her happy and smile.”

- “When we started with my first patient, we listened to the music with her and she danced in her bed and sang the songs. It was exactly the way some of the Music & Memory videos had shown the patient respond.”

- “One lady talked rapidly all the time with nonsensical sentences and phrases. We put music on her and she settled down and when her favorite song came on (as identified by a family member), she actually started singing the song clearly. She had not been able to put a coherent sentence together in a long time.”

- “One gentleman who was angry, abusive, and used a lot of foul language immediately settled down and changed his demeanor when music was applied. His improved demeanor would persist for several hours following the music intervention. He had a background as a musician in his family’s bluegrass band.”

Discussion

Caregiving for individuals with AD and dementia has evolved into a significant public health concern,18 highlighting the need for additional research in this field. Results from this study align with other studies that have shown the emotional, cognitive, and social benefits for patients who regularly engage in music activities, such as listening to familiar songs.19 For example, a systematic review found that music may be an effective means of providing care to individuals with AD, but there were few randomized controlled studies to evaluate music intervention on memory in patients with AD.20 In patients with AD and dementia, listening to music may not only improve cognition and orientation but can also improve the patient’s attention and mood compared with usual care. Enhancing mood and quality of life is a key sought-after goal in caring for these patients while also promoting the well-being of their family members and caregivers.

Music noticeably arouses superfluous musical memories and associations and allows individuals to reminisce about their lives.18 Listening to a song from a prior special occasion can evoke memories and emotions associated with the occasion. Physiologically, music and inspired movement can impact a person’s respirations, blood pressure, brain waves, and pulse rate.18

Based on the results of this study, training or coaching caregivers and nurses to implement personalized music activities is a suitable, cost-effective way to bringing stimulating, enriching musical experiences to patients with AD and dementia. The findings indicate that personalized music can help reduce patients’ feelings of depression and anxiety, alleviate sadness and worry, improve mood, and reduce irritability.

Study limitations included inconsistencies in data collection among the nursing homes due to staffing levels and new staff with varying knowledge and skills related to the program and patients. It is important to note that all patients were not observed during the same period, as recruitment was ongoing and some patients were hospitalized, died, declined to use the MP3 player, or misplaced their player, which interfered the intervention. Patients were required to have a medical diagnosis of either dementia or AD to participate in the program, but data on patients’ stage of dementia or AD were not collected or readily available. Additional change in staging after admission for patients in long-term care was not necessarily evaluated in all of the participating nursing homes. If current staging documentation had been more accessible, the severity of, or the latter stages of, AD or dementia could have been evaluated and used to assess whether the intervention had any impact on the patients’ condition over time.

Lessons Learned

Including multiple people in a Music & Memory program fosters sustainability, collaboration, and wider impact, but it also comes with challenges and valuable lessons.

- Build a collaborative team: Collaboration fosters shared ownership and commitment to the program. Involve diverse stakeholders, including nurses, caregivers, family members, and volunteers.

- Provide training and education: Training ensures consistency and confidence in program implementation. Offer workshops or online training about the Music & Memory program, including technical setup and patient interaction.

- Leverage technology and resources: Simplify operations by centralizing resources and reducing redundancy in music purchases through a shared playlist.

- Encourage ongoing communication: Regular updates improve program effectiveness and team cohesion. Schedule weekly team meetings to review the program impact and suggest adjustments.

- Prepare for turnover: Staff changes can disrupt the program if knowledge is not transferred. Create a program manual or guide to ensure continuity when staff members leave.

- Foster a culture of enthusiasm: Passionate advocates keep the program thriving. Celebrate successes and recognize contributors in staff meetings or newsletters to keep morale high.

Conclusion

The results of the study demonstrated that a personalized music intervention may be a suitable and effective treatment for patients with AD and dementia in rural communities, particularly for improving the patient’s mood and quality of life. Additionally, this approach provides families and caregivers with an additional tool to potentially see positive changes in their loved one. Future studies should explore diverse cultural and rural settings, include larger sample sizes, and ensure more consistent implementation of the music intervention. Despite these considerations, a personalized music intervention has proven to be a safe and effective tool to improve the well-being of patients with AD and dementia in rural settings.

Information and data from this project were submitted to Tennessee Department of Health as a CMPQI Final Report for “Improvement of Quality of Life for Nursing Home Residents through the ‘Music and Memory’ Program.” This report is located on the TN.gov website at https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/program-areas/civil-monetary-penalty-program/TTU-Final-Report-2020_Music-and-Memory.pdf. Information was retrieved from this final report in writing this article.

Affiliations, Disclosures, & Correspondence

Authors: Kimberly Joyce Hanna, PhD • Shelia Hurley, PhD • Toni Roberts, DNP • Emily Lee, DNP • George Chitiyo, PhD • Ann Hellman, PhD • Barbara Jared, PhD

Affiliations:

Whitson-Hester School of Nursing, Tennessee Tech University, Cookeville, TN

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Kimberly Hanna, PhD, MSN, CNL

Dean and Professor of Nursing

Tennessee Tech University

Whitson-Hester School of Nursing

10 West 7th Street | Bell Hall (243)

P.O. Box 5001 | Cookeville, TN 38505

References

- Alzheimer's Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. Published 2025. Accessed May, 2025. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

- CDC. FastStats - Alzheimers Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published 2022. Accessed May 20, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/alzheimers.htm

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:315-373. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2017.02.001

- Dementia. World Health Organization. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia#:~:text=Worldwide%2C%20around%2055%20million%20people,and%20139%20million%20in%202050

- Russ T, Batty G, Hearnshaw G, Fenton C, Starr J. Geographical variation in dementia: systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;21(4):1012-1032. doi:10.1093ije/dys103

- US Census Bureau. Quick Facts. 2021. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/whitecountytennessee,overtoncountytennessee,putnamcountytennessee,TN,US/PST045221

- Chin N. The powerful benefits of music on memory loss. Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. Published February 11, 2021. Accessed March 5, 2025. https://www.adrc.wisc.edu/dementia-matters/powerful-benefits-music-memory-loss

- Suttie J. Can music help keep memory alive? A conversation with the makers of Alive Inside, a new documentary about how music is helping people with dementia. Greater Good Magazine. Published April 21, 2015. Accessed March 5, 2025. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/can_music_help_keep_memory_alive

- Bakerjian D, Bettega K, Cachu AM, Azzis L, Taylor S. The impact of music and memory on resident level outcomes in California nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(8):1045-1050.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.01.103

- Thomas, KS, Baier R, Kosar C, Ogarek J, Trepman A, Mor V. Individualized music program is associated with improved outcomes for U.S. nursing home residents with dementia. Am J of Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(9):931-938. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.04.008

- Vinoo D, Santos, JM, Leviyev M, et al. Music and memory in dementia care. Int J Neurorehabilitation. 2017;4(2):1-4. doi:10.4172/2376-0281.1000255

- Cohen D, Post S, Lo A, Lombardo R, Pfeffer B. “Music & Memory” and improved swallowing in advanced dementia. Dementia (London). 2020;19(2):195-204. doi:10.1177/1471301218769778

- Browning S, Watters R, Thomson-Smith C. Impact of therapeutic music listening on intensive care unit patients: a pilot study. Nurs Clin North Am. 2020;55(4):557-569. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2020.06.016

- Make a playlist. Playlist for Life. Published 2019. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.playlistforlife.org.uk/get-started/#

- Music & Memory certification training. Music & Memory. Accessed March 5, 2025. http://musicandmemory.org/landing/music-memory-certification-program/

- Music & Memory. Music & Memory at home: a caregiver’s guide to creating personalized playlists. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://musicandmemory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Guide-to-Creating-Personalized-Playlists.pdf

- Helmes E, Csapo KG, Short J. Standardization and validation of the Multidimensional Observation Scale for Elderly Subjects (MOSES). J Gerontol. 1987;42(40):395-495. doi:10.1093/geronj/42.4.395

- Clements-Cortes A. Music and medicine: a new year, a new challenge. Ann Longterm Care. Published January 10, 2017. Accessed March 5, 2025. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/altc/blog/music-and-medicine-new-year-new-challenge

- Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: randomized controlled study. Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):634-650. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt100

- Moreira S, Ricardo F, Moreira M. Can musical intervention improve memory in Alzheimer’s patients? evidence from a systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2018;12(2):133-142. doi:10.1590/1980-57642018dn12-020005