Implications of Neuropathology for Sexual Decision Making in Long-Term Residents With Cognitive Impairment

Abstract

Sexual activity and expression (SAE) are fundamental aspects of human experience. SAE remains a priority even for people experiencing acquired cognitive impairment (ACI) due to brain injury. Care facilities often struggle to balance autonomy with safety when residents with ACI want to engage in SAE. Current methods for evaluating a resident’s ability to consent to SAE make many practical modifications to traditional informed consent models, but they fail to account for variability related to disease etiology. This article proposes that including etiological considerations, such as prognosis, time since onset, and expected symptomatology, is necessary for the equitable evaluation of residents with ACI engaging in SAE. This article offers a framework to guide clinicians and facilities in assessing decision making capacity for SAE.

Citation: Ann Longterm Care. 2025. Published online October 7, 2025.

DOI:10.25270/altc.2025.11.005

Sexual activity and expressivity (SAE), including intimate contact and physical presentation, are fundamental aspects of human experience regardless of age, gender, or cognitive ability. Despite common stereotypes, many older people and those with cognitive impairment feel that sexuality is an important aspect of life.1,2 For those living in residential care facilities, however, facilitating SAE remains a challenge due to concerns about safety, liability, staffing limitations, and comfort of the resident’s loved ones.

Although people with acquired cognitive impairment (ACI) are more vulnerable to harm or exploitation, many still have fulfilling intimate relationships well into the course of their disease.3,4 While ACI can contribute to inappropriate or unsafe sexual behaviors, not all forms of SAE are inappropriate. Universal restriction of SAE directly violates residents’ ethical rights to privacy and bodily autonomy.5 This is especially concerning for residents who identify as LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or other), who are already at risk of facing bias from caregivers and clinicians. Professional and legal organizations increasingly advocate for equitable access to SAE.6,7

Facilities should make efforts to support appropriate SAE for residents with limited cognitive capacity.8 Yet the practical and ethical implications of how neuropathology affects sexual consent remain a critical and underutilized factor in the development and implementation of facility guidelines for SAE.

Current Approaches

These are common frameworks for assessing capacity for providing SAE consent:

- Person-centered approaches: Prioritize ongoing iterative evaluations, including staff, loved ones, and other care partners, with emphasis on bias management.8

- Contextual approaches: Intended for use in residents with mild cognitive disability, assessing consent ability using standard measures mediated by situational context (eg, some residents may have more developed social skills or be in more or less coercive relationships).

- Activity-specific approaches: Combine substituted judgment and best-interest standards; interdisciplinary committees (including providers, social workers, physical/occupational therapist, nurses, and patient representatives) may establish minimally restrictive boundaries around specific activities based on the individual’s apparent values and desires.9

- Functional approaches: Use neuropsychological assessments and structured interviews to determine cognitive ability and assess capacity, although score cutoffs may be arbitrary.10

- Integrated approaches: Use features of person-centered and functional strategies with an additional emphasis on contextual features of the resident’s relationships, social and sexual history, and religious beliefs. The specifics of implementation are varied and beyond the scope of this paper, but this is generally the most comprehensive approach.11

Advanced intimacy directives (AIDs) are being explored as a supplement to these approaches. Although not legally binding, AIDs serve as a record of a person’s baseline sexual beliefs and preferences and may guide the types of SAE activities allowed and with whom. However, AIDs cannot anticipate ongoing changes in desire, physical ability, or unexpected situational nuances.7,12

Universal challenges to AIDs include monitoring and enforcement of established boundaries, balancing the concerns of loved ones with the autonomy and privacy of residents, and determining how best to provide materials for sexual safety and comfort (eg, condoms, lubricants).8-11

While all approaches advocate for a holistic and multidisciplinary framework, none address how variable neuropathology may affect the resident’s personal autonomy or the authenticity of desire for SAE. Currently, only broad categories of developmental delay and unspecified dementia have been considered separately. Including specific etiological features, such as expected symptoms, acuity, and prognosis, would better balance the right to intimacy with risk of harm in the context of ACI.

Assessing Consentability

The capacity to provide informed sexual consent requires an understanding of relevant facts, the ability to rationally process risks and benefits, and the absence of coercion.13 Although many people with cognitive impairment cannot meet this strict standard, all retain capacity for varying degrees of self-determination. More practical criteria focus on voluntariness, safety, absence of exploitation or abuse, social appropriateness, and the ability to decline.8 The impact of disease acuity, specific features, and prognosis of ACI on these principles, particularly voluntariness and ability to decline, necessitate their inclusion in any complete assessment.

The concepts of autonomy and authenticity, while not directly assessed in a standard capacity evaluation, are critical for the types of supported decision making described above. The common goal of all current approaches is to help residents with cognitive impairment align their actions with their values. A resident who cannot meet strict capacity definitions may still be allowed some freedom if their care team can determine that their expressed desires are consistent with their underlying values (ie, that desires are both autonomous and authentic).

Implications for Autonomy and Voluntariness

Certain brain injuries have predictable behavioral patterns directly attributable to known neuropathology. Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is a classic example. It specifically impacts neural networks responsible for judgment and self-restraint, presenting as isolated personality changes (especially disinhibition, compulsive behaviors, and social inappropriateness, including hypersexuality) with relative preservation of other cognitive domains. Superficially, autonomy appears spared, and affected parties are often held socially and legally accountable for their actions. However, in a medical view, their behaviors can be directly attributed to the underlying disease process—degeneration of the frontal lobe.14,15

People with bvFTD often act impulsively, showing little consideration for potential risks as if unable to resist or decline participation.14 They may also behave amorally, with no concern for the rightness or wrongness of their actions, and often without any clear purpose or plan.15 This pattern of impairment is relatively consistent and predictable, regardless of the resident’s personality before a cognitive impairment diagnosis, almost as if compelled by an external force.

In contrast, consider a person with new memory deficits following a hypoxic brain injury. If they subsequently experienced an increase in SAE, it would be difficult to show that the voluntariness of that behavior was impaired due to brain injury. Such a profoundly life-altering event can affect personality, regardless of whether a brain injury occurred. Additionally, hypersexuality is not a predictable sequelae of hypoxic brain injury, whereas it is relatively common in bvFTD.15 Despite both people having a major neurocognitive disorder, those with bvFTD appear to have less voluntary control over their actions, warranting more restrictions to SAE than those with hypoxic injury.

Other frontal lobe lesions, including tumors, can cause similar symptoms. Like bvFTD, the clear pathophysiology of tumors functions like an external force. However, tumor effects often fluctuate considerably over the course of treatment and produces less consistent behavioral tendencies. A new behavior that does not resolve despite tumor resection may be more voluntary than was initially thought, while a behavior that starts postresection may either reflect a truly voluntary desire that was suppressed by the tumor or a permanent result of treatment. Additionally, intraparenchymal tumors (eg, gliomas) may have different effects than extra-axial tumors (eg, meningiomas), which compress brain tissue but are not intrinsically entangled with it. This condition requires more frequent and in-depth behavioral assessments. Strokes that involve the frontal lobes are more likely to cause physical symptoms and a variety of personality changes but often demonstrate more stable long-term clinical improvement.

The above cases emphasize the importance of disease-specific features, such as predictability of symptoms, presence of biomarkers, and fluctuating disease course on how we conceptualize voluntariness of action. Suppose any of the above individuals showed an ability to participate in safe, appropriate acts of SAE. Based purely on voluntariness and ability to decline participation, residents with bvFTD should be the most restricted, but any resident with known frontal involvement in their disease process should be approached with additional scrutiny.

Continuity of Self and Authenticity

Determining whether a decision is authentic is difficult, even in the best circumstances, and especially so following the identity disruption inherent to ACI. It is nearly impossible to accurately assess sensitive personal issues like sexuality, in which only the individual is aware of truly authentic desires (including whether they prefer to act on said desires). Nonetheless, situations will arise that force facilities to make such judgment. An understanding of how underlying neurological conditions impact continuity of self can help guide this process.

Although continuity of self is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition of authenticity, it has a major impact on how loved ones, facility staff, and the resident with ACI perceive behaviors. Continuity of self is particularly vulnerable to acuity of change, as the amount of time needed to establish a new authentic self varies.

Any brain disease resulting in permanent personality change will, at some point, force loved ones to come to terms with the idea that “the person I knew before isn’t coming back.” This experience varies greatly depending on the rate of change: gradual (as with most neurodegenerative disorders), stepwise (vascular dementia, multiple sclerosis), or sudden and catastrophic (stroke, traumatic brain injury). Because of this uncertainty, the acuity and reversibility of cognitive decline should be taken into consideration when evaluating a person’s ability to authentically consent to SAE.

The gradual changes of most dementias often feel continuous, like variations on a core identity. As the disease progresses, families may psychologically and emotionally separate from the person experiencing dementia, perhaps because no stable new authentic self is established. They may feel the person with dementia should retain the same core values as before disease onset. This perspective impacts the family’s substitute decision making, as they may feel compelled to protect the former self that feels more authentic. The resident with dementia, on the other hand, may have little insight into these changes, conceiving of their current self as authentic, potentially leading to conflict with their family.

Severe acute brain injuries (SABI) can disrupt the continuity of self that underlies our concept of personality and authenticity, leading to a sudden and lasting change in personality. Over time, this new personality may stabilize into what appears to be a distinct, separate identity. Although the injury itself could be viewed as part of that person, after enough times passes, significant personality shifts can make it difficult to reconcile the post-injury self with who they were before. For example, friends and family from before a SABI may know one “authentic” self, whereas friends made after the injury—who may even be unaware of the SABI—would recognize a very different “authentic” self. This new self is stable and may not be beholden to earlier values in the same way as someone undergoing slower changes.

Diseases with a fluctuating course are at the greatest risk of causing inauthentic SAE by temporarily disrupting a person’s continuity of self.16 For example, suppose a resident with a brain tumor initiates a relationship with a non-spousal partner. After undergoing surgical treatment, they feel deep regret and deny having truly desired the extramarital affair. After the fact, it is apparent that an external force (the tumor) compelled the inauthentic behavior, and that the resident should not have been allowed to consent to this type of SAE. A resident with an unresectable brain tumor, on the other hand, may warrant different treatment, as the external force becomes intrinsic given the expectation that it will remain with them through the end of their life.

New behaviors suspected to be caused by the underlying disorder should not be considered part of a new authentic personality if there is a reasonable expectation of returning to a prior personality. A reversibly altered state is comparable to intoxication, in that the presence of an external force interferes with the person’s ability to consent to an activity (ie, SAE). In cases where personality changes may be partially or fully reversible with time or medical interventions, additional restraint or paternalism may be warranted to establish continuity of desires before allowing a resident to act on new SAE. In cases of uncertainty, continuity may be the best, or perhaps only, available clue to suggest behavioral authenticity.

Disease-Specific Considerations

There is a prevailing societal bias that people with disabilities or of advanced age are inherently nonsexual. This is reflected in the literature by a heavy focus on managing inappropriate or compulsive sexual behaviors. In reality, hypersexuality is a relatively uncommon symptom; people with dementia are more likely to have a decline, rather than a dramatic increase, in sexual desire.17 However, this is not universal and does not imply a loss of desire for intimacy. Applying disease-specific knowledge when evaluating ability to consent offers a pathway to determine whether SAE warrants restrictions.

Hypersexuality

Distinguishing naturally high libido with disinhibition from true hypersexuality can be difficult, but is highly ethically relevant. Hypersexuality, defined as clinically significant compulsive or obsessive sexual behavior, is most heavily associated with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), although it is neither universal nor specific to the disorder. When hypersexuality is present, people with bvFTD are more likely to perpetrate sexual violence than be victims of it.14 Although people with other frontal lobe pathology may experience sexual disinhibition, they typically lack the specific isolated sociomoral deficit seen in bvFTD.15 Therefore, residents with this diagnosis may warrant tighter restrictions on interpersonal SAE due to the excessively high risk to others.

With Kluver-Bucy syndrome (KBS), which is caused by damage to the bilateral mesial temporal lobes, among other mechanisms, patients tend to express hyperorality, hypersexuality, and make frequent inappropriate advances toward others. Simultaneously, these patients have a calm and compliant nature, which may leave them open to exploitation. Instead of completely restricting SAE behavior, identifying a safer, closely monitored outlet for SAE may be more appropriate.18 KBS remains stable or show slight improvement, whereas conditions like bvFTD are progressive and warrant more frequent re-evaluations.

Certain conditions merit additional scrutiny for reversible causes of new or excessive SAE. Impulse control disorders are relatively more common in Parkinsons disease, where treatment with dopamine agonists are known to cause compulsive behaviors, including hypersexuality.19 Identifying and addressing these medication side effects may eliminate the need for further capacity assessment.

Atypical Expressivity

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA), characterized by outbursts of involuntary laughter or tears unrelated to emotional state, can be seen in neurodegenerative disorders, particularly in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.20 PBA may be concerning and misleading for care partners and staff, thereby limiting genuine intimacy. PBA is a well-described and treatable phenomenon that does not need to interfere with SAE if recognized. Parkinsonian syndromes cause profoundly decreased facial expressivity that could be misunderstood as a lack of engagement or interest in SAE. Affected persons also have difficulty initiating movement and may experience freezing episodes that could be misinterpreted as hesitation or unwillingness to participate. Setting expectations would facilitate desired SAE.

Conversely, alien limb phenomenon (seen primarily in corticobasal syndrome) presents as involuntary limb movements that may appear deliberate and goal directed, such as reaching and grabbing.21 Similarly, highly impulsive patients with frontal dysregulation may also reach inappropriately for others without conscious intent. Behaviors such as groping of breasts or buttocks may be misinterpreted as an attempt at SAE, though they may be distressing to both the patient and others. In such cases, restricting and avoiding behavioral triggers may actually be welcomed by these patients.

Impaired Communication

Lesional syndromes, often caused by strokes, result in predictable patterns of impairment with unique implications for comprehension and consent that vary by affected brain region. For example, some types of aphasia have impaired language production but retain good understanding of spoken or written language. Others with a comprehension deficit might be able to manage simple conversations but struggle with complex questions around SAE. Such residents require closer monitoring and alternative methods to assess SAE consent. Additionally, yes-no confusion can occur, necessitating different communication strategies for SAE consent.

People with the degenerative condition primary progressive aphasia may have a great deal of difficulty communicating with everyone except a significant other with whom they are very familiar. In these cases, the sexual partner may also serve as a translator, creating a potentially challenging conflict of interest that requires additional monitoring. Awareness of each person’s unique and expected deficits allows more tailored and accurate evaluation of their behaviors, particularly when there is limited knowledge about their prior sexual proclivities. This knowledge also improves adequate accommodations, allowing better participation in conversations around SAE despite language impairment.

Anosognosia

Anosognosia, an unawareness of one’s own deficits or disabilities, is common in multiple types of dementia, though not universal.22 Its anatomical basis is not well understood. Right hemisphere strokes can cause anosognosia for hemiplegia and total neglect of the left half of the world. Other conditions, such as psychosis and Anton syndrome (blindness without awareness of vision loss), also complicate this symptom.

Knowledge of oneself is a critical factor in decision making, as is understanding of one’s circumstances. Residents with partial or complete anosognosia seem to be at higher risk of expressing inauthentic desires because they are incapable of understanding certain critical factors. Anosognosia caused by stroke often resolves in 3 to 6 months, although some people have persistent symptoms.23 Unawareness of deficits in dementia, on the other hand, may fluctuate or be extremely stable and pervasive. Residents with this condition may be especially resistant to restrictions, warranting unique strategies to optimize communication.

Practical Questions for Facilitating Accurate Assessment

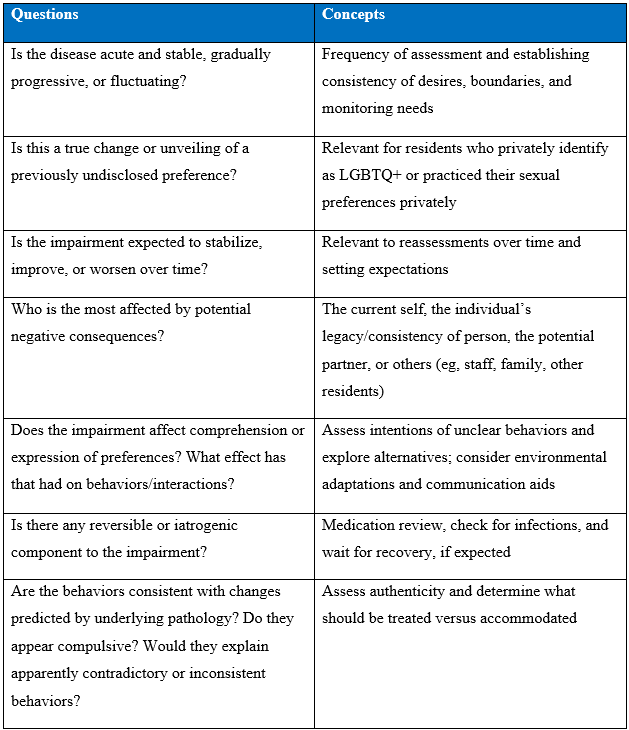

The preceding sections explored the unique impact that different causes of ACI have on current methods of obtaining consent to SAE from residents with ACI. The Table offers some practical questions to assist in the accurate assessment of constant ability for SAE.

Table 1. Sample Questions for Comprehensive Assessment of Consent to SAE

Abbreviations: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transexual, queer, and other; SAE, sexual activity and expressivity.

These questions build on the current assessment methods described in the introduction, with the goal of facilitating a more nuanced understanding of the relevant parties’ mental states. Awareness of basic disease features moderates the risk of allowing inauthentic or compelled behaviors, and in rare cases, may offer opportunities to reverse symptoms. Identifying unexpected behaviors or values, in the absence of unrecognized pathology, may actually support the authenticity and voluntariness of the behavior. Knowledge of the time course of the condition can also improve communication, guide use of decisional aids, and tailor expectation setting around SAE.

Conclusion

Moderation of SAE should never be relegated to an all-or-none policy, but instead be guided on a comprehensive assessment of each individual resident’s needs and desires, including their underlying disease process and prognosis. Excessive caution and paternalistic risks can unjustly restrict bodily autonomy, whereas insufficient monitoring of SAE may increase the risk of exploitation and preventable harm. Many clinical conditions have relatively predictable courses, symptoms, and challenges. Understanding the etiology can help weigh certain parts of the capacity assessment, facilitate better communication, and anticipate potential issues.

Achieving optimal balance between autonomy and authenticity with safety in care facilities requires applying modern understanding of neuropathology. Every experience of ACI, including its underlying cause, is unique and must be taken into consideration if we hope to honor the preferences of residents living with it.

Acknowledgements: Gavin Enck, PhD, and Rebecca Yarrison, PhD.

Author: Kaci McCleary, MD

Affiliations: Department of Neurology, HealthPartners, Saint Paul, MN. Research started at Ohio Health, Columbus, OH.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Kaci McCleary, MD

295 Phalen Blvd.

Saint Paul, MN 55130

References

- Youell J, Callaghan JE, Buchanan K. ‘I don't know if you want to know this’: Carers’ understandings of intimacy in long-term relationships when one partner has dementia. Ageing Soc. 2016;36(5):946-967. doi:10.1017/S0144686X15000045

- Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D, Tarzia L, Nay R, Wellman D, Beattie E. ‘I always look under the bed for a man.’ Needs and barriers to the expression of sexuality in residential aged care: the views of residents with and without dementia. Psychol Sexy. 2013;4(3):296-309. doi:10.1080/19419899.2012.713869

- Træen B, Villar F. Sexual well-being is part of aging well. Eur J Ageing. 2020;17(2):135-138. doi:10.1007/s10433-019-00534-2

- Brassolotto J, Howard L, Manduca-Barone A. "If you do not find the world tasty and sexy, you are out of touch with the most important things in life": resident and family member perspectives on sexual expression in continuing care. J Aging Stud. 2020;53:100849. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100849

- Tarzia L, Fetherstonhaugh D, Bauer M. Dementia, sexuality and consent in residential aged care facilities. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(10):609-613. doi:10.1136/medethics-2011-100453

- Sexual Health, Human Rights and the Law. World Health Organization; 2015. Accessed May 31, 2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564984

- Joy M, Weiss KJ. Consent for intimacy among persons with neurocognitive impairment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2018;46(3):286-294. doi:10.29158/JAAPL.003761-18

- Esmail S, Concannon B. Approaches to determine and manage sexual consent abilities for people with cognitive disabilities: systematic review. Interact J Med Res. 2022;11(1):e28137. doi:10.2196/28137

- Wilkins JM. More than capacity: alternatives for sexual decision making for individuals with dementia. Gerontologist. 2015;55(5):716-723. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu011

- Hillman J. Sexual consent capacity: ethical issues and challenges in long-term care. Clin Gerontol. 2017;40(1):43-50. doi:10.1080/07317115.2016.1198855

- Mahieu L, Anckaert L, Gastmans C. Intimacy and sexuality in institutionalized dementia care: clinical-ethical considerations. Health Care Anal. 2017;25(1):52-71. doi:10.1007/s10728-014-0286-5

- Sorinmade O, Ruck Keene A, Peisah C. Dementia, sexuality, and the law: the case for advance decisions on intimacy. Gerontologist. 2021;61(7):1001-1007. doi:10.1093/geront/gnaa093

- Assessment of Older Adults With Diminished Capacity: A Handbook for Psychologists. American Bar Association on Law and Aging and the American Psychological Association; 2018. Accessed May 31, 2025. https://www.apa.org/pi/aging/programs/assessment/capacity-psychologist-handbook.pdf

- Dubljević V. The principle of autonomy and behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. J Bioeth Inq. 2020;17(2):271-282. doi:10.1007/s11673-020-09972-z

- Diehl-Schmid J, Perneczky R, Koch J, Nedopil N, Kurz A. Guilty by suspicion? Criminal behavior in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2013;26(2):73-77. doi:10.1097/WNN.0b013e31829cff11

- Stirland LE, Ayele BA, Correa-Lopera C, Sturm VE. Authenticity and brain health: a values-based perspective and cultural education approach. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1-6. doi:10.3389/fneur.2023.1206142

- Benbow SM, Beeston D. Sexuality, aging, and dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(7):1026-1033. doi:10.1017/S1041610211002537

- Lilly R, Cummings JL, Benson DF, Frankel M. The human Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Neurology. 1983;33(9):1141-1145. doi:10.1212/wnl.33.9.1141

- Weintraub D, Claassen DO. Impulse control and related disorders in Parkinson's disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;133:679-717. doi:10.1016/bs.irn.2017.05.006

- Nabizadeh F, Nikfarjam M, Azami M, Sharifkazemi H, Sodeifian F. Pseudobulbar affect in neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2022;100:100-107. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2022.04.003

- Fisher CM. Alien hand phenomena: a review with the addition of six personal cases. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(3):192-203. doi:10.1017/S0317167100052729

- Mondragón JD, Maurits NM, De Deyn PP. Functional neural correlates of anosognosia in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2019;29:139-165. doi:10.1007/s11065-018-9392-9

- Vocat R, Staub F, Stroppini T, Vuilleumier P. Anosognosia for hemiplegia: a clinical-anatomical prospective study. Brain. 2010;133(12):3578-3597. doi:10.1093/brain/awq297