Screening and Staging Tools for Dementia

Abstract

Dementia represents a significant global health challenge with increasing prevalence as populations age worldwide. This article reviews the evolution of dementia screening and staging approaches, tracing their development from the historical concept of "senile dementia" to the current biomarker-based diagnostic paradigm. We examine traditional staging systems including the Global Deterioration Scale, Mini-Mental State Examination, and Montreal Cognitive Assessment, alongside specialized clinical trial assessment tools such as the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale and Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes. The emergence of blood-based biomarkers—including plasma p-tau181, p-tau217, Aβ42/40 ratio, neurofilament light chain, and glial fibrillary acidic protein—represents a transformative shift in dementia diagnostics, offering minimally invasive, cost-effective methods that achieve diagnostic accuracy comparable to more expensive neuroimaging techniques. This transition from symptom-based syndrome classification to biologically defined disease processes enables earlier intervention, personalized treatment strategies, and improved clinical outcomes. As disease-modifying therapies emerge, the integration of these advanced diagnostic tools into clinical practice will be essential for optimizing patient care in long-term care settings.

Citation: Ann Longterm Care. 2026. Published online January 9, 2026.

DOI:10.25270/altc.2026.01.007

Dementia, a syndrome characterized by progressive cognitive decline and functional impairment, affects millions of individuals worldwide. As the global population ages, the prevalence of dementia is expected to increase, placing a significant burden on health care systems and caregivers. Accurate and timely diagnosis of dementia is crucial for providing appropriate care, support, and treatment. Over the past several decades, the approach to dementia screening and staging has evolved significantly, reflecting advances in research and a growing understanding of the disease process. This evolution has been driven by scientific breakthroughs, particularly the development of disease-modifying treatments and the ability to identify biomarkers associated with specific forms of dementia. These advances have necessitated changes in screening and staging tools to better align with the current understanding of dementia pathology and to facilitate early intervention. This article provides an overview of the various staging systems and screening tools used in dementia care, highlighting their development, key features, and clinical applications, while also discussing the impact of scientific advancements on the evolving landscape of dementia staging.

In the 1980s and earlier, the term "senile dementia" was commonly used to describe cognitive decline in older adults, which was considered normal aging at the time. This term was often used interchangeably with "senility," reflecting the belief that cognitive decline was a normal part of aging. However, as research into dementia progressed, it became clear that cognitive decline was not an inevitable consequence of growing older. The term "Alzheimer's disease," first described by Alois Alzheimer in 1906, gained more prominence in the medical community. As a result, there was a shift toward more specific diagnoses based on the underlying causes of dementia. The publication of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980 played a significant role in this transition.1 The DSM-III introduced specific diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other types of dementia, such as vascular dementia and dementia due to other medical conditions. This move toward more precise diagnostic categories helped to distinguish between different types of dementia and their associated symptoms, risk factors, and potential treatments. The increased specificity in dementia diagnosis also facilitated more targeted research efforts and the development of tailored interventions for individuals with different forms of dementia.

Dementia Staging

The traditional staging of dementia has been used by health care professionals for several decades. This staging system originated from the work of Barry Reisberg and colleagues in the 1980s, who proposed the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) for assessing the progression of AD. The GDS divided the disease into seven stages, which were later simplified into the more commonly used categories of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), mild, moderate, and severe dementia. This staging system is based on the severity of cognitive impairment and the impact on daily functioning. It has been widely used in clinical settings and research to guide diagnosis, treatment, and care planning.

In the early 2000s, the Alzheimer's Association (AA) introduced its three-stage model (early, middle, and late) to help families and caregivers better understand the changes that occur throughout the course of AD. This staging system is based on the severity of symptoms and the level of assistance required by the individual. The AA staging has become widely used by caregivers, support groups, and educational resources to provide a more relatable and accessible way of describing dementia progression.

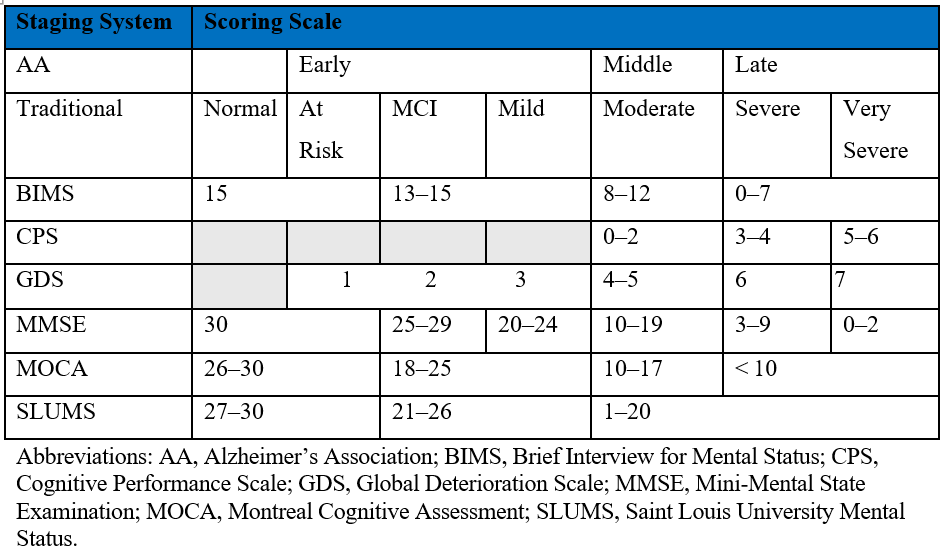

The staging of dementia continues to evolve with various organizations and diagnostic manuals proposing different staging systems to better understand and manage the progression of the disease. Examples with their scoring scales are shown in the Table.

Table. Dementia Staging Systems and Associated Scoring Scales

Global Deterioration Scale

Developed by Dr Barry Reisberg, the GDS is a widely used tool for assessing the progression of AD and other forms of dementia. The scale ranges from 1 to 7, with stage 1 representing no cognitive decline and stage 7 indicating very severe cognitive decline. Each stage is characterized by specific cognitive, functional, and behavioral changes.2 The GDS is commonly used by health care professionals to help guide treatment decisions, communicate with patients and their families, and track the progression of the disease over time. The scale is based on a comprehensive evaluation of an individual's cognitive abilities, daily functioning, and overall level of independence.

Mini-Mental State Examination

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a widely used cognitive screening tool developed by Marshall Folstein and colleagues in 1975.3 The MMSE consists of 11 questions that assess various cognitive domains, including orientation, memory, attention, language, and visuospatial abilities. The maximum score is 30 points, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment. A score of 24 or below is often used as a cutoff for potential dementia. Researchers have extensively validated the MMSE and it remains commonly used in clinical settings to screen for cognitive impairment and to monitor changes in cognitive function over time. However, the limitations of the MMSE include its lack of sensitivity to MCI and potential for cultural and educational bias.

Brief Interview for Mental Status

The Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) is a cognitive assessment tool specifically designed for use in nursing home settings. It was developed as part of the Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0, a comprehensive assessment tool used in US nursing homes. The BIMS consists of seven items that assess repetition, temporal orientation, and recall. Scores range from 0 to 15, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment. The BIMS has been shown to have good psychometric properties and is often used to identify cognitive impairment among nursing home residents. It is quicker to administer than the MMSE and is less affected by educational level.

Cognitive Performance Scale

The Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) is another assessment tool used in nursing home settings. It is derived from the MDS and uses five MDS items to create a score that ranges from 0 (intact cognition) to 6 (severe impairment). The CPS assesses cognitive function based on daily decision-making ability, short-term memory, ability to make self-understood, and eating independence. The CPS has been shown to correlate well with the MMSE and is often used to identify cognitive impairment and stage dementia severity in nursing home residents. The CPS is less time-consuming than the MMSE and does not require direct patient testing, making it easier to administer in long-term care (LTC) settings.

Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination

The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination is a 30-point cognitive screening tool developed by the Division of Geriatric Medicine at Saint Louis University. It was designed to detect MCI and early dementia. The SLUMS assesses orientation, memory, attention, and executive function through 11 items. Scores range from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment. The SLUMS has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity for detecting MCI and dementia. It is often used as an alternative to the MMSE, particularly in populations with higher levels of education, as it may be less affected by educational attainment.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a cognitive screening tool designed to detect MCI. It was developed by Ziad Nasreddine and colleagues in 1996.4 The MoCA assesses multiple cognitive domains, including attention, concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuospatial abilities, abstraction, calculation, and orientation. The maximum score is 30 points, with a score of 26 or above considered normal. The MoCA has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity for detecting MCI and has been validated in various languages and cultures. It is often used in clinical settings when a more comprehensive cognitive assessment is needed, particularly for individuals with higher levels of education or when the MMSE may not be sensitive enough to detect MCI.

Clinical Trial Staging

Clinical trials for dementia treatments require precise, standardized assessment tools to measure disease progression and treatment efficacy. These specialized instruments go beyond the general staging systems used in clinical practice, offering greater sensitivity to subtle cognitive and functional changes. Unlike routine clinical assessments, trial-specific measures must detect meaningful therapeutic signals while minimizing variability across diverse patient populations and multiple research sites. The following validated scales represent the gold standard for quantifying cognitive decline, functional status, and global changes in dementia clinical trials, providing the rigorous metrics necessary for regulatory approval of new therapies.

Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale

The Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) is a widely used primary outcome measure in clinical trials for AD. Developed by Richard Mohs and colleagues in 1984, the ADAS-Cog assesses cognitive function across various domains, including memory, language, praxis, and orientation.5 The scale consists of 11 tasks, with scores ranging from 0 to 70, where higher scores indicate greater cognitive impairment. The ADAS-Cog has been extensively validated and is considered the gold standard for assessing cognitive function in AD clinical trials. It is sensitive to changes in cognitive function over time and has been used to demonstrate the efficacy of various AD treatments. However, the ADAS-Cog has some limitations, such as its length of administration and potential for ceiling effects in MCI.

Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes

The Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) is a global assessment tool used to stage the severity of dementia in clinical trials. It is derived from the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, which was developed by John C. Morris in 1993.6 The CDR assesses six domains: memory, orientation, judgment and problem-solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care. The CDR-SB is calculated by summing the scores from each of the six domains, with scores ranging from 0 to 18. Higher scores indicate greater impairment. The CDR-SB has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of dementia severity and is often used as a secondary outcome measure in AD clinical trials. It is sensitive to changes over time and can help track the progression of the disease.

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Clinical Global Impression of Change

The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) is a global assessment tool used in clinical trials to evaluate the overall change in a patient's condition. It is based on the Clinical Global Impression scale, which was developed by Guy and Bonato in 1976. The CGIC is a 7-point scale that ranges from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). The rating is based on the clinician's assessment of the patient's overall change in cognitive function, behavior, and activities of daily living since the start of the study. The CGIC is often used as a secondary outcome measure in AD clinical trials and provides a clinically meaningful assessment of the patient's overall response to treatment.

Activities of Daily Living Scales

Activities of daily living (ADL) scales are used in clinical trials to assess a patient's ability to perform basic self-care tasks. Various ADL scales are used, such as the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living, the Barthel Index, and the Functional Activities Questionnaire.7 These scales typically assess activities such as bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and feeding. ADL scales are important outcome measures in AD clinical trials, as they provide insight into the functional impact of the disease and the patient's response to treatment. Preserved ADL function is a key goal of AD management, as it directly relates to the patient's quality of life and the burden on caregivers.

Biomarkers and Emerging Diagnostics

The landscape of dementia diagnosis has undergone a significant transformation in recent years, moving from reliance solely on clinical symptoms and psychometric testing to incorporating objective biological markers. This shift represents a fundamental change in our approach to dementia, particularly AD, enabling diagnosis before the onset of significant cognitive symptoms and facilitating targeted therapeutic interventions.

Blood-based biomarkers have emerged as the most promising advance in dementia diagnostics, offering several advantages over traditional approaches: they are minimally invasive, cost-effective, and readily scalable for widespread clinical implementation. Recent developments have yielded several key biomarkers with relevance to LTC settings:

- Plasma p-tau181 and p-tau217: These phosphorylated tau species have demonstrated remarkable diagnostic accuracy. Recent studies show plasma p-tau217 can differentiate AD from non-AD dementia with 90% to 95% accuracy, comparable to cerebrospinal fluid and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging.8 P-tau181 levels begin rising 5 to 10 years before symptom onset, offering a window for early intervention.9

- Plasma Aβ42/40 Ratio: The ratio of amyloid beta peptides in plasma correlates strongly with brain amyloid deposition. When combined with age and apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype, this marker achieves over 85% concordance with amyloid PET findings.10 Commercial tests are now available that could potentially eliminate the need for costly PET scans in many patients.

- Neurofilament light chain (NfL): A marker of neuronal damage and axonal injury, plasma NfL is not specific to AD but serves as a sensitive indicator of neurodegeneration. Recent longitudinal studies demonstrate that elevated NfL levels predict more rapid cognitive decline across dementia types11 and may help identify patients who would benefit from more intensive management strategies.

- Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP): This marker of astrocytic activation has emerged as a powerful predictor of future cognitive decline. Recent data show plasma GFAP increases up to 15 years before symptom onset in individuals carrying familial AD mutations and correlates strongly with amyloid burden.12

- Multimarker panels: The most promising diagnostic approach combines multiple blood biomarkers with basic clinical information. The PrecivityAD test, for example, integrates plasma Aβ42/40, APOE genotype, and age to predict brain amyloidosis with accuracy exceeding 80%.13 Similar panels incorporating tau markers are showing even higher accuracy.

The shift toward biomarker-based diagnosis represents a fundamental change in our conceptualization of dementia—from a symptom-based syndrome to a biologically defined disease process. For LTC providers, this transition offers unprecedented opportunities for earlier intervention, more personalized care, and potentially better outcomes for residents with dementia.

As our understanding of the underlying pathology of different forms of dementia continues to grow, it is likely that staging systems will further evolve to incorporate biomarker data and to better reflect the distinct trajectories of various dementia subtypes. This shift toward a more precise, biomarker-based approach to diagnosis and staging will enable earlier intervention, personalized treatment strategies, and improved clinical trial design. As research continues to advance our understanding of dementia, it is essential for clinicians to stay informed about the latest developments in screening, staging, and biomarker-based diagnosis. By leveraging these tools and incorporating them into clinical practice, health care professionals can improve the accuracy of diagnosis, optimize treatment strategies, and ultimately enhance the quality of life for individuals affected by dementia in the era of disease-modifying therapies.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

- Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psych. 1982;139(9):1136-1139. doi:10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-Mental State": A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

- Rosen W G, Mohs R C, Davis K L. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(11):1356-1364. doi:10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356

- Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412-2414. doi:10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914-919. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016

- Palmqvist S, Janelidze S, Quiroz YT, et al. Discriminative Accuracy of Plasma Phospho-tau217 for Alzheimer Disease vs Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. JAMA. 2020;324(8):772-781. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12134.

- Janelidze S, Mattsson N, Palmqvist S, et al. Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer's disease: relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer's dementia. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):379-386. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0755-1.

- Schindler S E, Bollinger J G, Ovod V, et al. High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology. 2019;93(17):e1647-e1659. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000008081.

- Götze K, Vrillon A, Dumurgier J, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain as prognostic marker of cognitive decline in neurodegenerative diseases: A clinical setting study. Alzheimer's Res Ther. 2024;16(1):231. doi:10.1186/s13195-024-01593-7.

- Chatterjee P, Pedrini S, Stoops E, et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein is elevated in presymptomatic familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature Med. 2023;29(4):760-767. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01137-1.

- Li Y, Schindler S E, Bollinger J G, et al. Validation of Plasma Amyloid-β 42/40 for Detecting Alzheimer Disease Amyloid Plaques. Neurology. 2022;15;98(7):e688-e699. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013211.

Affiliations, Disclosures & Correspondence

Richard G. Stefanacci, DO, MGH, MBA, AGSF, CMD1, 2, 3

Affiliations:

1 Thomas Jefferson University, Jefferson College of Population Health, Philadelphia, PA

2 Inspira LIFE, Mullica Hill, NJ

3 TauRx Therapeutics Management, Aberdeen, Scotland

Disclosure:

Dr Stefanacci serves as Chief Medical Officer for TauRx Therapeutics Management.

Address correspondence to:

Richard G. Stefanacci, DO, MGH, MBA, AGSF, CMD

Email: Richard.Stefanacci@Jefferson.edu

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Annals of Long-Term Care or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Key Takeaways

- Dementia screening and staging have shifted from cognitive tests (Mini-Mental State Examination, Global Deterioration Scale) to blood-based biomarkers (plasma p-tau181, p-tau217, amyloid-β ratios), enabling biologically defined diagnosis before cognitive symptoms and achieving diagnostic accuracy comparable to neuroimaging.

- Blood biomarkers are minimally invasive, cost-effective, and suitable for routine clinical and long-term care use, supporting earlier detection, personalized management, and alignment with emerging disease-modifying therapies.

- The transition from symptom-based syndromic classification to biologically defined disease processes represents a paradigm shift, enabling earlier intervention, more personalized treatment strategies, and potentially optimized patient outcomes as disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer disease and other dementias emerge.