Design of Buccinator Flaps for Oronasal Fistula Repair: A Technical Review and Case Series

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background: Oronasal fistula (ONF) repair remains a significant challenge in patients with cleft lip and palate, particularly when local palatal tissue is insufficient. Regional flaps, including the buccal myomucosal flap (BMMF) and the facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap, offer reliable reconstructive options. This study reviews the surgical anatomy, design, and clinical outcomes of these buccinator-based flaps in ONF repair.

Methods: This retrospective case series included 13 patients who underwent ONF repair using a BMMF or a FAMM flap between 2017 and 2024. Patient demographics, fistula characteristics, surgical details, postoperative care, and outcomes were collected and analyzed.

Results: Six patients underwent BMMF reconstruction, while 7 received FAMM flaps. Successful fistula closure was achieved in 66.7% of patients in the BMMF group, with flap dehiscence occurring in 2 cases, both associated with digital manipulation. The FAMM flap cohort had a 100% fistula closure rate but exhibited a high incidence (86%) of postoperative scar contracture, with 4 patients requiring contracture release.

Conclusions: Based on this experience, the authors propose an algorithm for flap selection in ONF repair. Posteriorly based BMMFs are well suited for fistulas at the junction of the hard and soft palate (Type III) and the posterior third of the hard palate (Type IV). Superiorly based FAMM flaps are preferred for anterior ONFs, particularly those extending into the alveolus. The central hard palate remains a reconstructive challenge, with FAMM flaps offering better reach, though they require staged inset and debulking. Both BMMF and FAMM flaps provide vascularized tissue for ONF closure with minimal donor site morbidity. Strategic flap selection based on fistula location optimizes outcomes while mitigating complications.

Introduction

Reconstruction of symptomatic oronasal fistulas (ONF) represents a significant technical challenge in patients with orofacial clefts. Documented incidence of ONF varies within the literature, but meta-analyses suggest the incidence of fistula occurrence is between 6.4% and 8.6%.1-3 When documenting outcomes from palatal surgery, it is important to distinguish between physiologic and pathologic fistulas. Physiologic fistulas represent a portion of the palate that was intentionally left unrepaired for later reconstruction, such as the alveolus, which may be closed in a delayed fashion at the time of bone grafting.3,4 Pathologic fistulas occur because of surgical dehiscence leading to fistula formation.4-7 One must also consider the size and symptomatic nature of the fistula when deciding on need, timing, and preferred technique for reconstruction. Small fistulas may be asymptomatic and may not require surgery. Depending on the location and size, larger fistulas may result in morbidity associated with nasal regurgitation of food, air escape with speech causing hypernasality, and challenging oral hygiene.3,4,8

Symptomatic ONFs are ideally reconstructed using palatal tissue. Unfortunately, fistulas often arise because of an inherent paucity of palatal tissue and excessive tension during palatoplasty. These conditions persist over time, with scarring from prior surgeries further limiting tissue mobility. There are certainly cases where a small but poorly located fistula is symptomatic and may be treated with local flaps of palatal and nasal mucosa.5,9-12 Additionally, wide undermining analogous to the mobilization achieved with primary palatoplasty techniques is often a successful technique for fistula repair.13,14 However, if a fistula is large enough to result in symptoms requiring repair, it should prompt the cleft surgeon to ask whether local tissues are sufficient to achieve a successful repair or whether regional tissue recruitment is necessary to optimize surgical success.14,15 Local-regional flaps allow the cleft surgeon to augment palatal and nasal mucosa to limit tension with supple unscarred tissues with improved vascularity.

While free tissue transfer is occasionally required for complex cases, regional flaps suffice for most ONF repairs.16,17 Examples commonly utilized include posterior pharyngeal flaps18-21 to address tissue deficiency in the velum, tongue flaps22-25 for a wide variety of palatal defects, and cheek flaps 26-33 based on the buccinator and its varying blood supply. Pharyngeal flaps have a unique application for treatment of velar defects with associated velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD). Tongue flaps are versatile, but they can be bulky, require flap division, and can have negative effects on articulation.34,35 Alternatively, the redundant blood supply of the buccinator muscle and oral mucosa makes it an ideal and versatile donor site for oral reconstruction.26-33

This article aims to review 2 commonly used axial pattern flaps from the cheek to repair ONF: the buccal myomucosal flap (BMMF) and the facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap. We discuss the anatomy and design of axial pattern flaps, examine current literature, and propose a surgical algorithm for ONF repair. This manuscript is intended to serve as an educational resource for residents, offering detailed insights into the surgical techniques, anatomical considerations, and outcomes associated with these procedures.

Axial Pattern Cheek Flaps for ONF Repair

Surgical anatomy. The cheek is a multilayered structure consisting of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), buccinator muscle, submucosa, and oral mucosa. The outermost layer, the SMAS, is a fibrous network that lies below the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, supporting the facial muscles and skin and contributing to the overall contour and function of the cheek. Deep to the SMAS lies the buccinator muscle, which runs parallel in the space between the maxilla and the mandible. It originates from the surface of the mandible, the alveolar processes of the mandible and maxilla, and the pterygomandibular raphe, inserting onto the orbicularis oris muscle at the modiolus.36-38 The buccinator compresses the cheeks against the teeth, aiding in mastication by keeping food between the molars and assisting in the initial phase of swallowing. Additionally, it aids in air expulsion, facilitates speech, and contributes to facial expressions such as smiling and frowning. Superficial and posterior to the buccinator muscle are the buccal fat pad, masseter muscle, and parotid gland. The parotid duct (Stenson duct) originates from the anterior border of the parotid gland, traverses the masseter muscle, and pierces the buccinator muscle to enter the oral cavity.36,37 The duct opens into the mouth opposite the second upper molar tooth and should be preserved during dissection. However, if damaged, parotid secretions can still be released.39

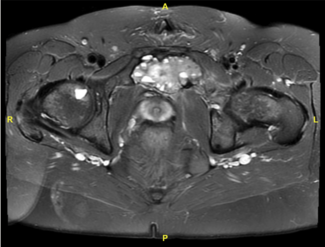

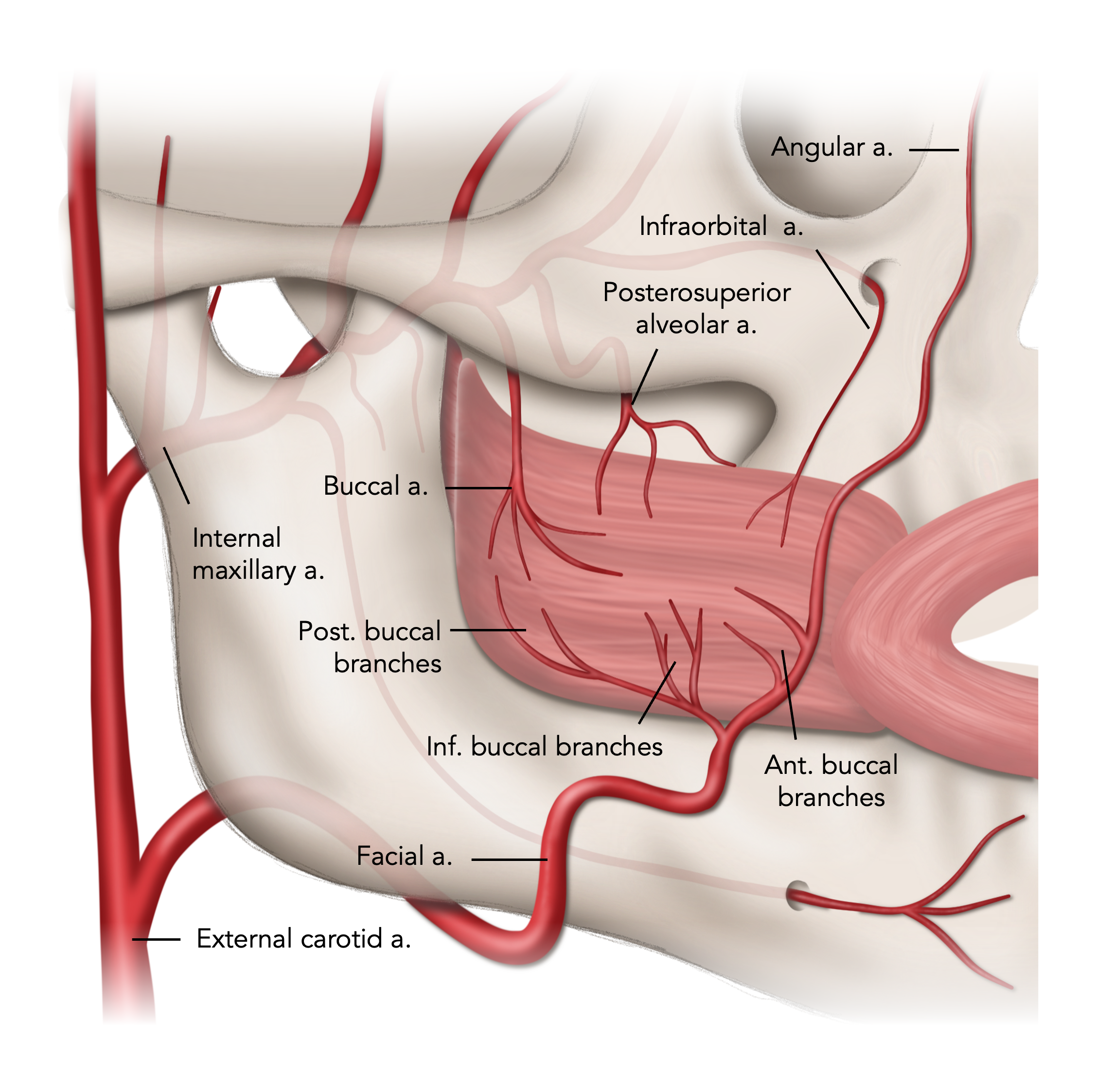

The arterial supply of the buccinator muscle is an extensive vascular anastomotic plexus comprised of the facial, buccal, and posterosuperior alveolar arteries (Figure 1).29,30,40 The facial artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, ascends over the mandible at the antegonial notch and traverses the cheek towards the medial canthus of the eye, where it is renamed the angular artery. As it passes over the buccinator, the facial artery gives off several branches, including the posterior, inferior, and anterior buccal branches, which supply the muscles in their respective areas.29,40 Numerous variations of the facial artery have been documented.41 However, the posterior buccal branch is always present; it is the largest of the branches and supplies the posterior half of the buccinator muscle.40,41 The buccal artery is a branch of the second part of the internal maxillary artery, which runs deep to the mandibular ramus and anterior to the pterygoid muscles. It supplies the posterior aspect of the buccinator muscle, forming an anastomosis with the posterior buccal branches of the facial artery. The posterosuperior alveolar artery, a more distal branch of the internal maxillary artery, supplies the posterior-superior area of the buccinator. The infraorbital artery, after exiting the infraorbital foramen, provides small branches to the anterior portions of the buccinator.29,40 These anastomotic networks are found along the lateral surface of the muscle and within the muscle fibers.29,30,40

Figure 1. Arterial supply of the buccinator muscle.

The venous drainage system of the buccinator is even richer and more varied. It is composed of the deep facial vein anteriorly and the pterygoid plexus posteriorly.28,30 The deep facial vein runs transversely between the buccal fat pad and buccinator, joining with the facial vein to eventually drain into the common facial vein and the external jugular vein.28-30 The pterygoid plexus is a network of veins between the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles that collects blood from the region supplied by the maxillary artery. The plexus drains into the maxillary vein, which subsequently joins the retromandibular vein and eventually contributes to the external jugular vein.28,30 Given the redundant vascular supply, the pedicled BMMFs are consistently well perfused and allow numerous pedicle designs to serve the needs of diverse fistula challenges.29

The buccinator muscle receives motor innervation through the buccal branch of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), which emerges from behind the parotid gland and runs horizontally across the face, superficial to the masseter muscle, before reaching the buccinator.30,42 The buccinator and mentalis muscles are the only facial muscles innervated from their superficial surface. Sensory innervation to the buccinator is provided by the buccal nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V3), which courses alongside the buccal artery.43

Terminology. The terminology used to describe a buccinator myomucosal flap is nuanced. Some terms that have been introduced include Bozola flap,29 Zhao flap,40 FAMM flap,32,33,44-46 BMMF,31,39,47-50 pedicled facial buccinator (FAB) flap,41 myomucosal cheek flap,45 buccal musculomucosal flap,26,51 buccal mucosal transposition flap,52 and island cheek flap.53 Confusion and redundancy exist because of the numerous ways to classify these flaps, including by their vascular supply (buccal artery or facial artery), location of flap base (superior, inferior, posterior, or anterior), and design (pedicle or island). These reviews provide a comprehensive description of the terminology surrounding buccinator myomucosal flaps.27,54 While they suggest new naming conventions, ambiguity in the nomenclature continues to exist.

We discuss buccinator-based myomucosal flaps in terms of their predominant vascular supply (buccal or facial artery). Within the craniofacial community, these flaps are most commonly referred to as BMMF and FAMM flaps, respectively.31-33,39,44-50 Both are axial-patterned flaps that contain buccal mucosa, submucosa, and parts of the buccinator muscle. BMMFs are based on the buccal artery and have a posterior base, though anteriorly based flaps with the same name have been described.28,39,47,55-57 FAMM flaps are based on the facial artery and can theoretically be designed with superior, inferior, or anterior bases; however, the superior- and inferior-based FAMM flaps are most commonly described for intraoral repair.32,33,44-46 BMMF and FAMM flaps have been used for numerous reconstruction efforts including defects of the lip, tongue, alveolar ridge, palate, floor of mouth, pharyngeal walls, nasal septum, eyelid, skull base, and maxilla; however, we will focus on their use for ONF repair in this article.58

ONF may vary significantly based on size, location, and symptoms.3,4 The Pittsburgh fistula classification system is a well-accepted nomenclature that precisely denotes the location for clinical discourse and outcomes research.59 The classification includes 7 types, but ONFs can present as a combination of types in clinical practice. The 7 types are: Type I: Uvula; Type II: Soft palate; Type III: Junction of the hard and soft palate; Type IV: Hard palate; Type V: Junction of the primary and secondary palate (in Veau IV Clefts); Type VI: Lingual-alveolar; and Type VII: Labial-alveolar. The Pittsburgh classification is used to highlight the varying locations and clinical applicability of different flap techniques for ONF closure.

BMMF design. The BMMF, also known as the posteriorly based buccinator flap, was first described by Bozola in 1989.29 It is a reliable and versatile option for repairing ONFs, particularly those at the junction of the hard and soft palate (Type III) and the posterior hard palate (Type IV).14,60 BMMFs are generally used for fistulas up to 2 to 3 cm in diameter, though they have been described as effective for closing fistulas as large as 5 cm.29,30,33

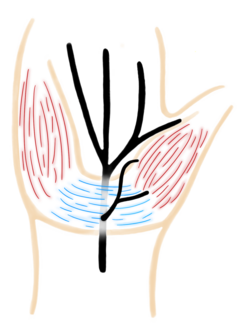

The flap’s neurovascular supply includes the buccal artery, the posterior buccal branch of the facial artery, the buccal venous plexus, and innervating nerves.29 Typical flap elevation includes design of the flap based on the retromolar trigon with a 1- to 2-cm wide design, parallel to the occlusal plane located caudal to the parotid papilla (Figure 2).30,55,61 To maximize reach, the flap tip is located just shy of the oral commissure, but alternative designs including spindle-shaped, L-shaped, fish-mouth, bilobed, or 3-lobed flaps have been described to increase both length and available tissue.30,55,61 Typically, the flap measures 1 to 3 cm in width and 3 to 5 cm in length. Flaps as long as 10 cm and as wide as 5 cm have been described; however, the tradeoff donor-site closure tension and need for skin graft must be considered.29,30,40,55,61,62 Location of the buccal artery can be confirmed with a Doppler but typically is not necessary unless an islandized flap is planned.

Figure 2. Intraoperative view of a buccal myomucosal flap design, based in the retromolar trigone and extending toward the oral commissure, positioned inferior to Stenson’s duct.

For flap elevation, the mucosa is incised anteriorly, superiorly, and inferiorly, and the flap is elevated from anterior to posterior.28-30 At the anterior limit of the flap, elevation proceeds deep to the submucosa overlying the modiolus where the vertically oriented muscle fibers of the orbicularis oris are seen. Once the dissection passes posterior to the orbicularis oris, elevation must include fibers of the buccinator muscle. Some authors have advocated dissection within the buccinator muscle, leaving more superficial fibers, while others advocate full-thickness muscle elevation.28-30,55 We typically proceed from a more superficial, intramuscular dissection anteriorly to a deeper plane, including full thickness of the muscle posteriorly, and taking care to preserve the buccopharyngeal fascia posteriorly to limit buccal fat pad herniation into the mouth.

Approximately 1 cm anterior to the pterygomandibular raphe, the main neurovascular bundle of the buccinator may be encountered, which must be carefully preserved for flap viability.30 The flap may be designed as a pedicled or island flap.29,40 Both can pivot and rotate up to 180 degrees, allowing for versatile inset options. However, to improve mobility, the mucosa at the flap base can be divided from the underlying muscle to create an island flap after the buccal artery has been identified and preserved.40,62 The island flaps can also be tunneled under the pterygomandibular ligament to avoid the occlusal plane.30,40 In our series of cases, islandization has not been necessary. Typically, adequate mobilization has been achieved, and dissection may be terminated at the retromolar trigon without identification of the buccal artery. The mucosal and submucosal pedicle may be preserved to reduce tension, minimize the risk of pedicle injury, and optimize venous drainage via the submucosal plexus. For posterior fistulas and in younger children, the pedicle can typically be passed behind the dentition without impingement across the occlusal plane (Figure 3A-C). In patients where the secondary molars have erupted, particularly the second molar, the chance of occlusal trauma to the pedicle may be higher. A contralateral bite block should be considered to prevent excessive mouth closure and protect the pedicle (Figure 3D-F). The patient should return to the operating room 2 to 4 weeks later for division and inset of the flap. When occlusal trauma is not a concern, division, and inset can be deferred or delayed until the time of another planned procedure.

Figure 3. (A) A patient with a history of orofacial digital syndrome and cleft palate repaired elsewhere. The patient had severe maxillary restriction and a large hard palate (Type IV) fistula. Fistula repair was undertaken prior to palatal expansion to avoid an enlarging fistula. (B) The patient underwent a conversion Furlow palatoplasty and a left buccal myomucosal flap (BMMF) for coverage of the posterior and middle 50% of the hard palate. (C) The flap reached the posterior third of the palate, but closure was compromised anteriorly, leading to tip necrosis and recurrence of the fistula, which did not respond to readvancement. (D) Revision surgery with a right BMMF taken across the occlusal plane. (E) A contralateral bite block was placed for flap protection. (F) Healing progressed well until the patient disrupted the flap inset with digital manipulation, resulting in a small, non-functional residual fistula.

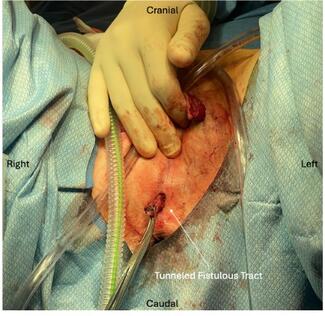

The use of posteriorly based BMMFs for primary and secondary palatoplasties has gained popularity in recent years following the publications of Robert Mann.55,63 In Mann’s buccal flap palatoplasty procedure, the velum is lengthened and the levator veli palatini is repositioned by cutting the velum free of the posterior hard palate.55 The resulting nasal and oral lining defect is filled with bilateral BMMFs (one side is used for nasal lining and the other is utilized for oral lining).55 In many cases of fistula repair, the periphery of the fistula may be incised circumferentially to recruit sufficient oral lining to facilitate primary closure of the nasal lining (Figure 4A and B). In these cases, a greater oral defect is created, necessitating a local-regional flap for oral lining; s unilateral BMMF may be sufficient (Figure 4C and D).

Figure 4. (A) A patient with a history of bilateral cleft lip and palate repaired elsewhere and 1 prior fistula repair attempt, presenting with a Type III fistula. (B) Markings for a conversion Furlow palatoplasty and left buccal myomucosal flap (BMMF). (C) Intraoperative view following flap elevation and inset, with the BMMF passed behind the dentition without occlusal impingement. (D) Healed flap, with division and inset planned for a future procedure.

In other cases, a desire to lengthen the velum may necessitate augmentation of oral and nasal lining, or poor tissue quality may dictate bilateral flaps for both oral and nasal closure (Figure 5). These procedures have been described as fistula repairs with and without concurrent secondary speech surgery.14,15,49,63,64 When a BMMF is used for nasal lining, it is tunneled through the palate. This results in an obligate physiologic fistula underlying the flap pedicle, but it is covered by the pedicle and remains asymptomatic. At the time of secondary division and inset, the surgeon must be aware of this obligate fistula and close it by preserving a small flap of mucosa based on the palatal component of the flap and incising circumferentially around the fistula to allow inset of the oral lining.

Figure 5. A patient with a history of a Veau 2 cleft palate repaired elsewhere and 4 prior fistula repair attempts, presenting with a large Type IV fistula. The patient underwent palate re-repair with intravelar veloplasty and fistula closure using bilateral buccal myomucosal flaps and acellular dermal matrix by the senior author. (A) Preoperative view of bilateral buccal flaps prior to division and inset. (B) Postoperative view following flap division and inset.

The use of BMMFs is most commonly discussed for primary/secondary palatoplasty and fistula repairs at the junction of the hard and soft palate (Type III, Figure 4A). While authors have described their deployment for coverage of lining defects in the posterior two-thirds of the hard palate (Type IV, Figure 3A), the senior author’s anecdotal experience suggests they are most reliable at the junction of the hard and soft palate and the posterior third of the hard palate.55 Comparing outcomes of BMMFs in the closure of ONF is challenging because of the low frequency, variability, and unique idiosyncrasies of each fistula. Nonetheless, many series report complete fistula resolution,31,39,65,66 while others show success rates ranging from 69% to 96%.39,64,67 Donor site morbidity is consistently low, and BMMFs are associated with fewer reported issues related to pedicle bulk and scar contracture compared with FAMM flaps.

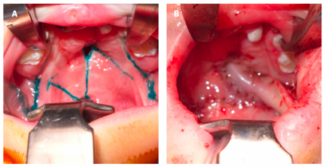

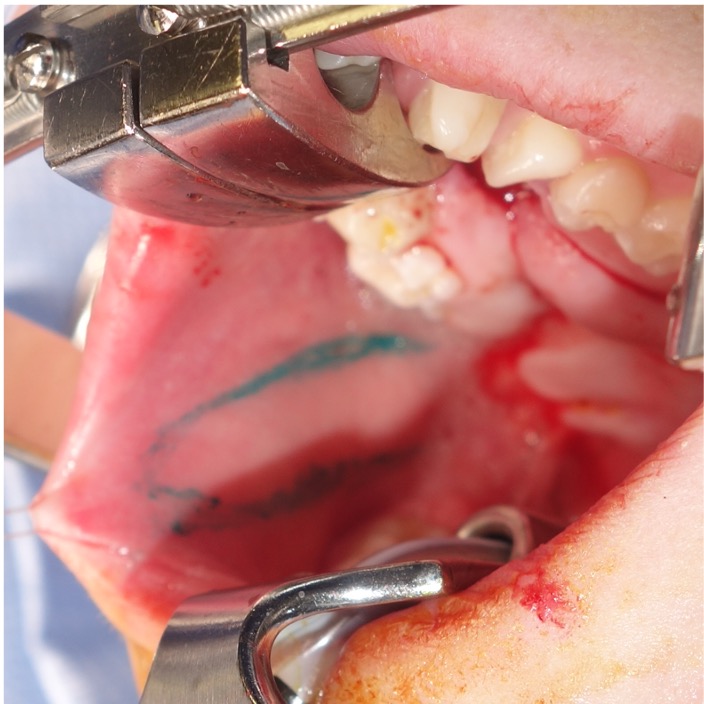

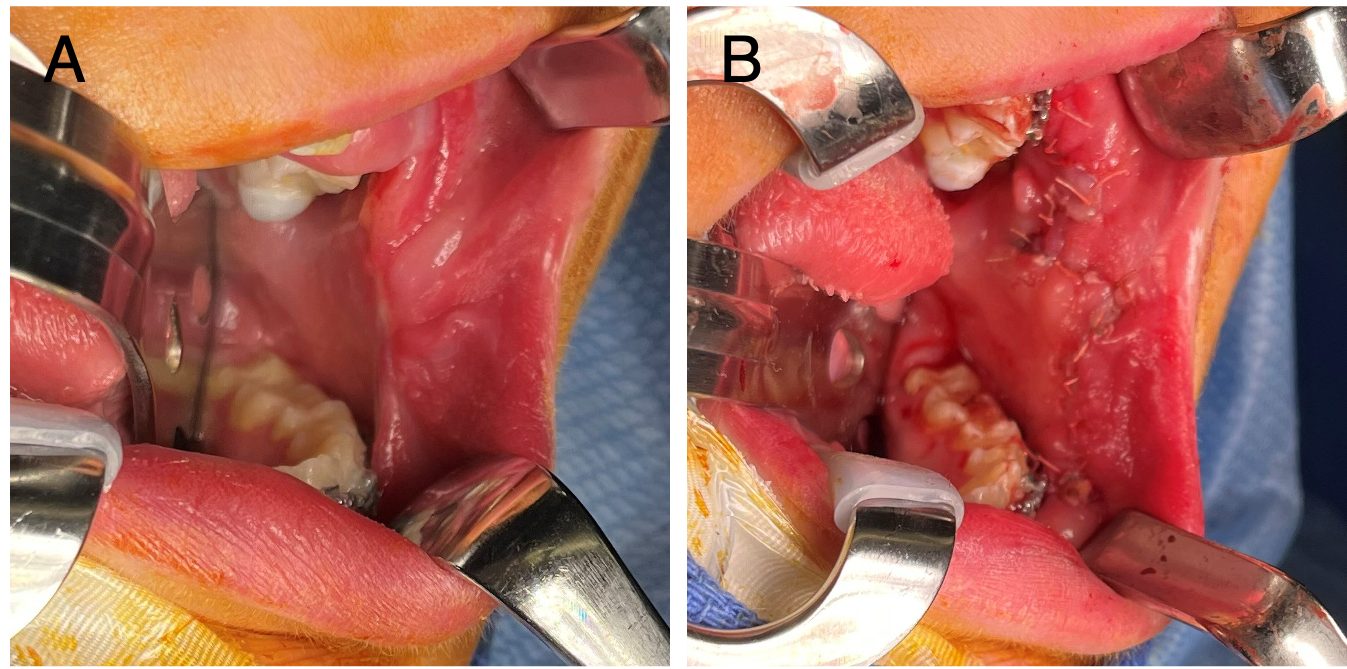

FAMM flap design. The FAMM flap was introduced by Pribaz in 1992 and has been widely used in various intraoral reconstruction applications.46 This flap is useful for closing large anterior palatal fistulas in ONF repair (Type IV-VII, Figure 6A).14,60 FAMM flaps have been used for fistula repair up to 5 cm in diameter, making them suitable for extensive defects when local tissue is inadequate.33

Figure 6. (A) A patient with a history of a Veau 3 cleft lip and palate repaired elsewhere and 1 prior fistula repair attempt, presenting with a Type IVVI/VII fistula. (B) Inset of the facial artery musculomucosal flap prior to division and debulking, with redundant tissue present.

Design of the FAMM flap is based along the facial artery and includes mucosa, submucosa, and portions of the buccinator muscle and orbicularis oris muscle.46 Unlike the buccal artery, the facial artery has well-documented variations.41,68 Therefore, the flap design should always involve identifying the facial artery using a Doppler probe to ensure adequate perfusion, and the artery must be included for the entire length of the flap.68,69 Venous drainage of the flap is through the buccal plexus and, therefore, the facial vein is not required in flap design.44,45 However, if excluded, the pedicle mucosal base must be adequately wide (at least 2 cm) to prevent venous congestion.70,71 When approached intraorally, the facial nerve lies deeper than the plane of the facial artery and has divided into smaller branches, protecting it from clinically significant injury.33

After Doppler identification of the facial artery, the flap is marked on the cheek mucosa along its trajectory.46 The initial description of the FAMM flap included superior- and inferior-based flaps.46 The inferiorly based FAMM flap receives its blood supply from the facial artery, while a superiorly based flap relies on retrograde flow from the angular artery.46 In ONF repair, superior-based flaps are most commonly used; however, inferior-based flaps have been described for fistula repair in the posterior palate.70,72 For a superior-based flap, the pedicle base is located in the gingivolabial sulcus and the flap extends obliquely to the area of the second or third molar.46 The anterior limit is approximately 1 cm behind the oral commissure, and the posterior limit is bounded by the parotid papillae.33,46,70 The size of the flap typically measures 2 to 3 cm in width and 4 to 6 cm in length, allowing primary closure of the donor site, but can extend to 8 to 9 cm depending on the defect size and location.46,70 The inferior-based FAMM flap is essentially the opposite of the superior-based flap: the base is at the second or third molar tooth, extending obliquely up to the gingivolabial sulcus.46 The flap size and orientation follow similar guidelines as the superior-based flap.33,46,70

Once the flap boundaries have been appropriately marked, the facial artery is identified, either distally or anteriorly. In the distal approach, the distal end of the flap is incised through the mucosa and muscle until the facial artery is located, clipped, and sectioned.33,46 The anterior approach involves an incision at the anterior border of the flap (1 cm behind the oral commissure) through the orbicularis oris muscle to identify the superior labial artery, which is then traced back to the facial artery.70 For superiorly based flaps, the flap is raised inferior to superior and deep to the facial artery, including the buccinator and parts of the orbicularis oris near the oral commissure.46 Collateral vessels are clipped and sectioned during flap elevation.46 Like the BMMF, the FAMM flap has excellent mobility and can be designed as an island flap to improve its rotation and reach.30,73

The cheek donor site can be closed primarily if the flap is less than 3 cm wide.30,74 Alternatively, to reduce the risk of scar contracture, the donor site can be left open to be granulated, grafted, or closed with buccal fat pad advancement.44,75 For ONF repair, if an open alveolar defect exists, the flap can be passed through the defect, eliminating the need for a bite block and staged flap division (Figure 6B).44,71,72 If pedicle division is necessary, the flap can be sectioned and inset after 3 weeks.33,46,70

Methods and Materials

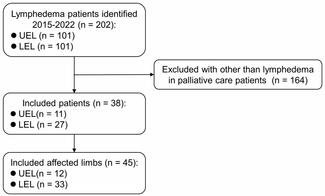

This retrospective case series included 13 patients who underwent ONF repair by the senior author (S.A.R.) with either a BMMF or FAMM flap between 2017 and 2024. The cohort included 5 males and 9 females with a median age of 11.0 years (range, 2.1 to 18.7 years). All patients had a history of cleft lip and palate with varying degrees of previous surgical interventions. Data were collected from patient medical records, including demographics, fistula characteristics, surgical details, postoperative care, and follow-up outcomes.

BMMF Group

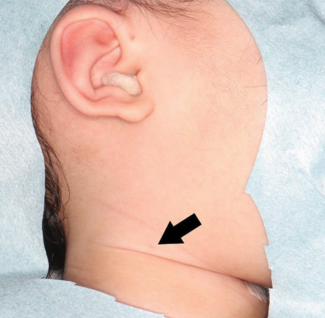

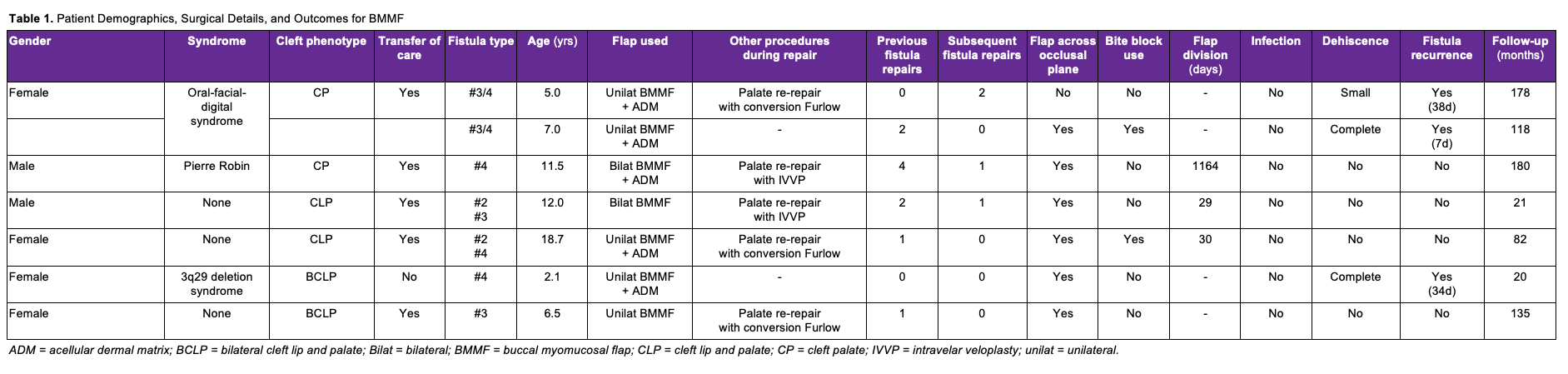

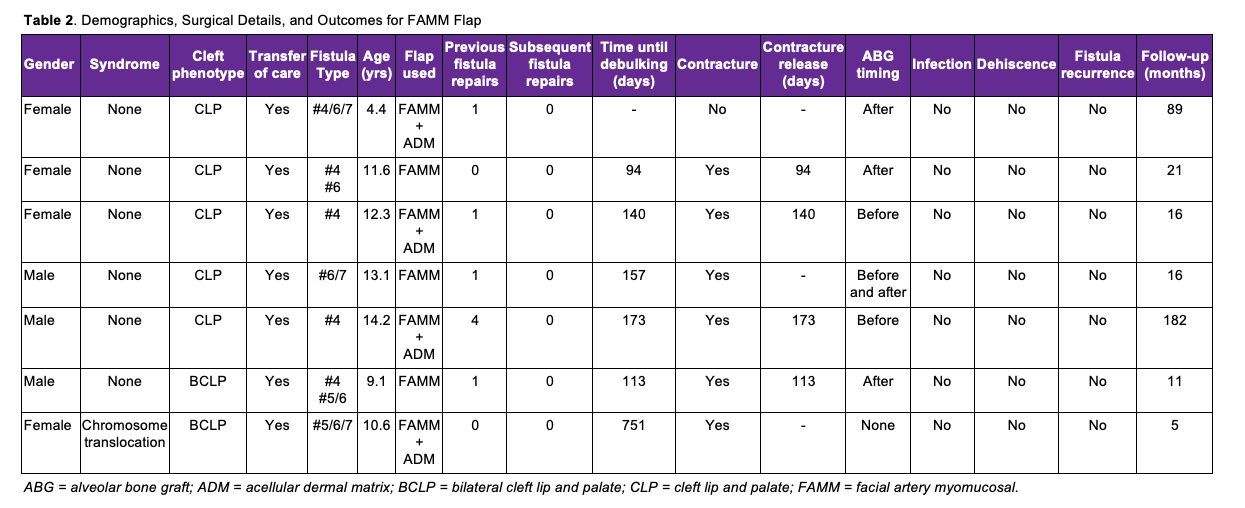

Six patients underwent 7 fistula repairs using the BMMF (Table 1). The cohort consisted of 2 males and 4 females, with repairs performed at a median age of 7.0 years (range, 2.1-18.7 years). The median length of follow-up was 118 months (range, 20-180 months). Two patients had isolated cleft palate, 2 had unilateral cleft lip and palate, and 2 had bilateral cleft lip and palate. The median hospital length of stay (LOS) was 32 hours (range, 30-48 hours). The buccal flap was brought across the occlusal plane in 6 of the 7 flaps. A bite block was used in 2 cases to protect the pedicle from masticatory trauma. The flap was divided and inset in 3 cases, with 2 requiring early inset. Successful fistula closure was achieved in 66.7% (4) of the patients. Two patients experienced flap dehiscence. The first patient was a 2-year-old who had recurrent sinus infections and nasal drainage, as well as reported digital manipulation of the flap. The second patient underwent concurrent Furlow palatoplasty for VPD and Type IV fistula repair with a unilateral BMMF (Figure 3B). The fistula size was decreased, but loss of the distal tip of the BMMF resulted in a 2- to 3-mm fistula recurrence, which was unsuccessfully treated with re-elevation and advancement of the flap (Figure 3C). Severe palatal constriction raised concerns about potential fistula enlargement with palatal expansion, and a third attempt at fistula repair with a contralateral BMMF (Figure 3D) was undertaken with a protective bite block (Figure 3E). Digital manipulation by the patient resulted in flap dehiscence, but secondary healing resulted in no functional fistula after orthodontic treatment (Figure 3F).

FAMM Flap Group

Seven patients underwent 7 fistula repairs using the FAMM flap (Table 2). The cohort consisted of 3 males and 4 females with repair; the median age was 10.8 years (range, 4.4-14.2 years). The median length of follow-up was 16 months (range, 5-182 months). Five patients had unilateral cleft lip and palate, and 2 patients had bilateral left lip and palate. The median hospital LOS was 34 hours (range, 30-36 hours). Flap debulking was performed in 6 cases, and the median time until debulking was 5.0 months (range, 3.1-25.0 months). Scar contracture was noted in 6 cases, with 4 requiring scar contracture release (Figure 7). The median time until contracture release was 4.2 months (range, 3.1-5.8 months). Successful fistula closure was achieved in 100% of the patients. No patients had flap dehiscence, necrosis, or infection.

Figure 7. (A) Postoperative scar contracture causing trismus following a facial artery musculomucosal flap. (B) Surgical release of the scar contracture with serial Z-plasties.

Surgical Considerations and Challenges of Buccinator-Based Flaps

Based on our case series and clinical experience, we propose the following approach to the use of buccinator-based flaps in ONF repairs. Posteriorly based BMMFs represent a workhorse flap for reconstructing fistulas located at the junction of the hard and soft palate (Type III), as well as the fistulas involving the posterior one-third of the hard palate (Type IV). Additionally, patients with Type II fistulas of the velum often require secondary palatal surgery with an intravelar veloplasty (IVVP) to address VPD. In these cases, addition of tissue at the junction of the hard and soft palate will relieve tension on velar repairs and allow palatal lengthening, as described by Mann and others.14,15,49,63,64 The posteriorly based BMMF can be rotated 90 degrees and can easily reach Type III and posterior Type IV fistulas. This location presents challenges because the excursion of the native mucoperiosteal flaps is minimal, and the tension is highest because of the need to preserve the greater palatine neurovascular pedicle. Addition of tissue is beneficial in achieving primary healing. Previous studies have documented coverage of the posterior two-thirds of the hard palate with posteriorly based myomucosal flaps.55 This may be achievable with modifications such as extending the flap to harvest mucosa from the upper and lower lip, but the risk of tip necrosis could jeopardize closure in the central hard palate.

In infants or children with primary dentition, occlusal trauma is typically minimal or not a concern when using posteriorly based BMMFs. After eruption of the first secondary, and certainly the second, molars, the potential for occlusal trauma is much higher and surgeons should have a low threshold for placement of an acrylic bite block or occlusal splint on the contralateral dentition to open the bite and prevent trauma (Figure 3E). Timely division and inset of the flaps should be planned 2 to 3 weeks later. In settings without occlusal interference, division may be undertaken electively in conjunction with another planned procedure prior to eruption of the secondary molars.

Superiorly based FAMM flaps reliably cover anterior hard palate fistulas, but proper flap inset remains a challenge. Typical alveolar clefts (Type VI/VII) can be closed with local tissue mobilization at the time of alveolar bone graft. The FAMM flap is helpful when a more extensive fistula extends from the alveolus posteriorly into the hard palate. This includes alveolar fistulas with concurrent Type IV fistulas in patients with unilateral clefts and Type V fistulas in patients with bilateral clefts. In these cases, a FAMM flap with a superior pedicle base may be brought into the palate through the alveolar defect after palatal expansion and used to close the hard palate fistula. In our practice, this is considered a staged reconstruction. A closed soft tissue envelope is necessary for successful bone grafting and, in the setting of a complex hard palate fistula, it is best to ensure fistula closure before bone grafting. Additionally, the FAMM flap pedicle introduces redundant tissue into the gingivobuccal sulcus, which covers the dentition and limits access for orthodontics. Division and inset of the flap are necessary to facilitate ongoing care. For this reason, we typically perform the fistula repair with the FAMM flap and allow 3 months of healing before a second stage. At this time, the flap pedicle is divided, the flap is debulked to increase space for the bone graft to fill the alveolar defect, a bone graft is placed, and Z-plasty revision of the donor site is commonly undertaken. In our series, a high percentage (86%) of patients undergoing FAMM flap procedures had some degree of scar contracture of the vertically oriented donor site scar. This often responded to massage and allowed for scar maturation, but, in some cases, the contracture was sufficiently persistent or so severe that Z-plasty was required. Therefore, Z-plasty should be prophylactically considered when the team returns for bone grafting. It should be noted that this procedure introduces non-keratinized mucosa into the cleft. If a treatment plan includes medialization of the canine or placement of dental implants, a gingival graft may be necessary at the site. Alternatively, dental restoration may rely on a bridge or other prosthetics, as teeth and dental implants should ideally be placed in a keratinized epithelium for optimal periodontal health and hygiene.

The central aspect of the hard palate represents a watershed that presents challenges to the use of cheek flaps for fistula closure. Greater mobility of the hard palate flaps may facilitate primary closure, but, when large fistulas are present and/or multiple procedures have been attempted to close them, remote tissue is recommended. In cases with alveolar defects, the FAMM flap can be extended with a robust axial blood supply and easily reach the middle of the hard palate. In our experience, the BMMF was less reliably able to reach this point (Figure 3). If a gap in the dentition is not present, it will be necessary to cross the occlusal plane and use a bite block for protection. In our series, these cases resulted in a dehiscence because of patient compliance issues. For fistulas in this location, collaborative decision making should be undertaken with the family to balance the preference for a check-based flap or tongue flap.

Limitations

This manuscript represents a review of the anatomy, terminology, and technical approaches for the use of buccinator-based flaps for ONF repair derived from the literature and the senior author’s experience. We also present a single-surgeon clinical case series utilizing flaps of various designs to investigate a systematic approach to ONF repair. However, reconstruction of palatal fistula remains complex, challenging, and highly individualized. As clinical needs and surgical techniques vary, the insights presented here may not be fully generalizable to all ONF cases or surgical practices.

Conclusions

BMMFs and FAMM flaps are effective and versatile options for the repair of ONF in patients with cleft lip and palate. These axial pattern flaps, derived from the cheek, offer robust vascularity, minimal donor site morbidity, and flexibility in addressing defects of varying sizes and locations. The BMMF is better suited for posterior defects, while the FAMM flap is more effective in the setting of anterior defects. The central hard palate can be reliably reached with a FAMM flap brought through a dental gap; however, in cases without such an access point, protecting a flap inset and preventing dental trauma presents true challenges. Our proposed algorithm, based on clinical experience and outcomes from our case series, highlights the significance of these flaps in achieving reliable and durable ONF closures.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Molly MacIsaac, BS1; Alexzandra Mattia, BS2; Jordan Halsey, MD1; S. Alex Rottgers, MD1

Affiliations: 1Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Florida; 2Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, Florida

Correspondence: S. Alex Rottgers, MD, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 601 Fifth Street South, Suite 611, St. Petersburg, FL 33701, USA. Email: srottge1@jhmi.edu

Ethics: This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Human Investigation Committee (IRB) of Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital approved this study (JHACH: IRB00417626). Informed consent for image publication was not required as all images are deidentified and contain no identifiable patient information.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

References

1. Jodeh DS, Nguyen ATH, Rottgers SA. Outcomes of primary palatoplasty: an analysis using the pediatric health information system database. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(2):533-539. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000005210

2. Hardwicke JT, Landini G, Richard BM. Fistula incidence after primary cleft palate repair: a systematic review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(4):618e-627e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000000548

3. Muzaffar AR, Byrd HS, Rohrich RJ, et al. Incidence of cleft palate fistula: an institutional experience with two-stage palatal repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1515-1518. doi:10.1097/00006534-200111000-00011

4. Cohen SR, Kalinowski J, LaRossa D, Randall P. Cleft palate fistulas: a multivariate statistical analysis of prevalence, etiology, and surgical management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(6):1041-1047.

5. Campbell DA. Fistulae in the hard palate following cleft palate surgery. Br J Plast Surg. 1962;15:377-384. doi:10.1016/s0007-1226(62)80062-9

6. Rossell-Perry P. Flap Necrosis after palatoplasty in patients with cleft palate. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:516375. doi:10.1155/2015/516375

7. Park MS, Seo HJ, Bae YC. Incidence of fistula after primary cleft palate repair: a 25-year assessment of one surgeon's experience. Arch Plast Surg. 2022 ;49(1):43-49. doi:10.5999/aps.2021.01396

8. Amaratunga NA. Occurrence of oronasal fistulas in operated cleft palate patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46(10):834-838. doi:10.1016/0278-2391(88)90044-4

9. Millard DR, Batstone JH, Heycock MH, Bensen JF. Ten years with the palatal island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970;46(6):540-547. doi:10.1097/00006534-197012000-00002

10. Henderson D. The palatal island flap in the closure of oro-antral fistulae. Br J Oral Surg. 1974;12(2):141-146. doi:10.1016/0007-117x(74)90122-x

11. Elsherbiny A, Grant JH III. Total palatal mobilization and multilamellar suturing technique improves outcome for palatal fistula repair. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;79(6):566-570. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000001216

12. Freda N, Rauso R, Curinga G, Clemente M, Gherardini G. Easy closure of anterior palatal fistula with local flaps. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21(1):229-232. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181c5a179

13. Denny AD, Amm CA. Surgical technique for the correction of postpalatoplasty fistulae of the hard palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(2):383-387. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000148650.32055.01

14. Rothermel AT, Lundberg JN, Samson TD, et al. A toolbox of surgical techniques for palatal fistula repair. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2021;58(2):170-180. doi:10.1177/1055665620949321

15. Buller M, Jodeh D, Qamar F, Wright JM, Halsey JN, Rottgers SA. Cleft palate fistula: a review. Eplasty. 2023;23:e7.

16. Schwabegger AH, Hubli E, Rieger M, Gassner R, Schmidt A, Ninkovic M. Role of free-tissue transfer in the treatment of recalcitrant palatal fistulae among patients with cleft palates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(4):1131-1139. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000110370.67325.ed

17. Chen HC, Ganos DL, Coessens BC, Kyutoku S, Noordhoff MS. Free forearm flap for closure of difficult oronasal fistulas in cleft palate patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90(5):757-762. doi:10.1097/00006534-199211000-00004

18. Witt PD, Myckatyn T, Marsh JL. Salvaging the failed pharyngoplasty: intervention outcome. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1998;35(5):447-453. doi:10.1597/1545-1569_1998_035_0447_stfpio_2.3.co_2

19. Barone CM, Shprintzen RJ, Strauch B, Sablay LB, Argamaso RV. Pharyngeal flap revisions: flap elevation from a scarred posterior pharynx. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(2):279-284.

20. Skoog T. The pharyngeal flap operation in cleft palate. A clinical study of eighty-two cases. Br J Plast Surg. 1965;18:265-282. doi:10.1016/s0007-1226(65)80046-7

21. Mercer NS, MacCarthy P. The arterial basis of pharyngeal flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(5):1026-1037. doi:10.1097/00006534-199510000-00004

22. Pigott RW, Rieger FW, Moodie AF. Tongue flap repair of cleft palate fistulae. Br J Plast Surg. 1984;37(3):285-293. doi:10.1016/0007-1226(84)90068-7

23. Jackson IT. Use of tongue flaps to resurface lip defects and close palatal fistulae in children. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;49(5):537-541. doi:10.1097/00006534-197205000-00011

24. Assunçao AG. The design of tongue flaps for the closure of palatal fistulas. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91(5):806-810. doi:10.1097/00006534-199304001-00008

25. Strujak G, Nascimento TC, Biron C, Romanowski M, Lima AA, Carlini JL. Pedicle tongue flap for palatal fistula closure. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(8):2146-2148. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000003042

26. Nakakita N, Maeda K, Ando S, Ojimi H, Utsugi R. Use of a buccal musculomucosal flap to close palatal fistulae after cleft palate repair. Br J Plast Surg. 1990;43(4):452-456. doi:10.1016/0007-1226(90)90012-o

27. Rahpeyma A, Khajehahmadi S. Buccinator-based myomucosal flaps in intraoral reconstruction: a review and new classification. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2013;4(1):25-32. doi:10.4103/0975-5950.117875

28. Licameli GR, Dolan R. Buccinator musculomucosal flap: applications in intraoral reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124(1):69-72. doi:10.1001/archotol.124.1.69

29. Bozola AR, Gasques JA, Carriquiry CE, Cardoso de Oliveira M. The buccinator musculomucosal flap: anatomic study and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84(2):250-257. doi:10.1097/00006534-198908000-00010

30. Fang L, Yang M, Wang C, et al. A clinical study of various buccinator musculomucosal flaps for palatal fistulae closure after cleft palate surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(2):e197-202. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000000411

31. Abdel-Aziz M. The use of buccal flap in the closure of posterior post-palatoplasty fistula. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(11):1657-1661. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.07.020

32. Ariffuddin I, Arman Zaharil MS, Wan Azman WS, Ahmad Sukari H. The use of facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) readvancement flap in closure of recurrent oronasal fistula. Med J Malaysia. 2018;73(2):112-113.

33. Ashtiani AK, Emami SA, Rasti M. Closure of complicated palatal fistula with facial artery musculomucosal flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(2):381-386; discussion 387-388. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000142475.63276.87

34. Al-Qattan MM. A modified technique of using the tongue tip for closure of large anterior palatal fistula. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47(4):458-460. doi:10.1097/00000637-200110000-00019

35. Kummer AW, Neale HW. Changes in articulation and resonance after tongue flap closure of palatal fistulas: case reports. Cleft Palate J. 1989;26(1):51-55.

36. Mortellaro C, Manuzzi W, Caligiuri F, et al. Surgical buccinator muscle myotomy in dentoskeletal Class II alterations. J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12(5):409-225; discussion 426. doi:10.1097/00001665-200109000-00002

37. D'Andrea E, Barbaix E. Anatomic research on the perioral muscles, functional matrix of the maxillary and mandibular bones. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28(3):261-266. doi:10.1007/s00276-006-0095-y

38. Hur MS, Kim HC, Won SY, et al. Topography and spatial fascicular arrangement of the human inferior alveolar nerve. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2013;15(1):88-95. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8208.2011.00335.x

39. Robertson AGN, McKeown DJ, Bello-Rojas G, et al. Use of buccal myomucosal flap in secondary cleft palate repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(3):910-917. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318182368e

40. Zhao Z, Li S, Yan Y, et al. New buccinator myomucosal island flap: anatomic study and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(1):55-64.

41. Rivera-Serrano CM, Oliver CL, Sok J, et al. Pedicled facial buccinator (FAB) flap: a new flap for reconstruction of skull base defects. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(10):1922-1930. doi:10.1002/lary.21049

42. Martínez Pascual P, Maranillo E, Vázquez T, Simon de Blas C, Lasso JM, Sañudo JR. Extracranial course of the facial nerve revisited. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2019;302(4):599-608. doi:10.1002/ar.23825

43. Hendy CW, Robinson PP. The sensory distribution of the buccal nerve. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;32(6):384-386. doi:10.1016/0266-4356(94)90030-2

44. Dupoirieux L, Plane L, Gard C, Penneau M. Anatomical basis and results of the facial artery musculomucosal flap for oral reconstruction. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;37(1):25-28. doi:10.1054/bjom.1998.0301

45. Bianchi B, Ferri A, Ferrari S, Copelli C, Sesenna E. Myomucosal cheek flaps: applications in intraoral reconstruction using three different techniques. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(3):353-359. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.04.021

46. Pribaz J, Stephens W, Crespo L, Gifford G. A new intraoral flap: facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90(3):421-429. doi:10.1097/00006534-199209000-00009

47. Shipkov H, Stefanova P, Hadjiev B, Uchikov A, Djambazov K, Mojallal A. The posterior-based buccinator myomucosal flap for palatal defects. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(5):1265-1266; author reply 1266. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2010.12.019

48. Chiang SN, Fotouhi AR, Grames LM, Skolnick GB, Snyder-Warwick AK, Patel KB. Buccal myomucosal flap repair for velopharyngeal dysfunction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152(4):842-850. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000010443

49. Qamar F, McLaughlin MM, Lee M, Pringle AJ, Halsey J, Rottgers SA. An algorithmic approach for deploying buccal fat pad flaps and buccal myomucosal flaps strategically in primary and secondary palatoplasty. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2023;60(7):865-874. doi:10.1177/10556656221084879

50. Jackson IT, Moreira-Gonzalez AA, Rogers A, Beal BJ. The buccal flap--a useful technique in cleft palate repair? Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41(2):144-151. doi:10.1597/02-124

51. Chen J, Zhao ZM, Li SK, et al. Buccal musculomucosal flap for reconstruction of wide vermilion and orbicularis oils muscle defect. Article in Chinese. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;23(6):493-495.

52. Oberna F, Takácsi-Nagy Z, Réthy A, Pólus K, Kásler M. Buccal mucosal transposition flap for reconstruction of oropharyngeal-oral cavity defects: an analysis of six cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99(5):550-553. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.009

53. Sasaki TM, Standage BA, Baker HW, McConnell DB, Vetto RM. The island cheek flap: repair of cervical esophageal stricture and new extended indications. Am J Surg. 1984;147(5):650-653. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(84)90133-8

54. Massarelli O, Vaira LA, Biglio A, Gobbi R, Piombino P, De Riu G. Rational and simplified nomenclature for buccinator myomucosal flaps. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;21(4):453-459. doi:10.1007/s10006-017-0655-9

55. Mann RJ, Neaman KC, Armstrong SD, Ebner B, Bajnrauh R, Naum S. The double-opposing buccal flap procedure for palatal lengthening. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(6):2413-2418. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182131d3e

56. Carstens MH, Stofman GM, Hurwitz DJ, Futrell JW, Patterson GT, Sotereanos GC. The buccinator myomucosal island pedicle flap: anatomic study and case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88(1):39-50; discussion 51-52.

57. Frohwitter G, Kesting MR, Rau A, et al. Pedicled buccal flaps as a backup procedure for intraoral reconstruction. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023;27(1):117-124. doi:10.1007/s10006-022-01040-7

58. Szeto C, Yoo J, Busato GM, Franklin J, Fung K, Nichols A. The buccinator flap: a review of current clinical applications. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;19(4):257-262. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e328347f861

59. Smith DM, Vecchione L, Jiang S, et al. The Pittsburgh Fistula Classification System: a standardized scheme for the description of palatal fistulas. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007;44(6):590-594. doi:10.1597/06-204.1

60. Comini LV, Spinelli G, Mannelli G. Algorithm for the treatment of oral and peri-oral defects through local flaps. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46(12):2127-2137. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2018.09.023

61. Ahl R, Harding-Bell A, Wharton L, Jordan A, Hall P. The buccinator mucomuscular flap: an in-depth analysis and evaluation of its role in the management of velopharyngeal dysfunction. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2016;53(5):e177-e184. doi:10.1597/14-283

62. Massarelli O, Gobbi R, Raho MT, Tullio A. Three-dimensional primary reconstruction of anterior mouth floor and ventral tongue using the 'trilobed' buccinator myomucosal island flap. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37(10):917-922. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2008.07.020

63. Goote PC, Adams NS, Mann RJ. Palatal lengthening with double-opposing buccal flaps for velopharyngeal insufficiency. Eplasty. 2017;17:ic21.

64. Abdaly H, Omranyfard M, Ardekany MR, Babaei K. Buccinator flap as a method for palatal fistula and VPI management. Adv Biomed Res. 2015;4:135. doi:10.4103/2277-9175

65. Denadai R, Zanco GL, Raposo-Amaral CA, Buzzo CL, Raposo-Amaral CE. Outcomes of surgical management of palatal fistulae in patients with repaired cleft palate. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31(1):e45-e50. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000005852

66. Varghese D, Datta S, Varghese A. Use of buccal myomucosal flap for palatal lengthening in cleft palate patient: experience of 20 cases. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6(Suppl 1):S36-S40. doi:10.4103/0976-237X.152935

67. Zhang B, Li J, Sarma D, Zhang F, Chen J. The use of heterogeneous acellular dermal matrix in the closure of hard palatal fistula. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(1):75-78. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.10.053

68. Braasch DC, Lam D, Oh ES. Maxillofacial reconstruction with nasolabial and facial artery musculomucosal flaps. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2014;26(3):327-333. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2014.05.003

69. Rabbani CC, Lee AH, Desai SC. Facial artery musculomucosal flap operative techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;149(3):511e-514e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000008859

70. Shetty R, Lamba S, Gupta AK. Role of facial artery musculomucosal flap in large and recurrent palatal fistulae. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2013;50(6):730-733. doi:10.1597/12-115

71. Lee JY, Alizadeh K. Spacer facial artery musculomucosal flap: simultaneous closure of oronasal fistulas and palatal lengthening. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(1):240-243. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000001904

72. Lahiri A, Richard B. Superiorly based facial artery musculomucosal flap for large anterior palatal fistulae in clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007;44(5):523-527. doi:10.1597/06-164.1

73. Jeong HI, Cho HM, Park J, Cha YH, Kim HJ, Nam W. Flap necrosis after palatoplasty in irradiated patient and its reconstruction with tunnelized-facial artery myomucosal island flap. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;39(1):24. doi:10.1186/s40902-017-0121-5

74. Rigby MH, Hayden RE. Regional flaps: a move to simpler reconstructive options in the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;22(5):401-406. doi:10.1097/MOO.0000000000000090

75. Ayad T, Kolb F, De Monés E, Mamelle G, Temam S. Reconstruction of floor of mouth defects by the facial artery musculo-mucosal flap following cancer ablation. Head Neck. 2008;30(4):437-445. doi:10.1002/hed.20722