Comparison of Multimodal Analgesia and Narcotic Regimen for Postoperative Pain Control of Plastic Surgery Breast Procedures

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background: Opioid analgesics are commonly used for postoperative pain management in plastic surgery, despite risks regarding dependence and complications. This study evaluates the noninferiority of multimodal analgesia compared with traditional narcotic regimens for postoperative pain management in breast reduction mammoplasty and tissue expander placement following mastectomy.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study of 171 patients (107 breast reduction, 64 tissue expander placement) was conducted at a single tertiary academic medical center between 2018 and 2022. Patients received either multimodal analgesia (preoperative acetaminophen 1000 mg, postoperative tramadol 50 mg q6h PRN, and gabapentin 300 mg TID) or narcotic analgesia (hydrocodone-acetaminophen 5-325 mg q6h PRN). Pain intensity was measured using Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pain intensity scores at the 2-week postoperative visit. Supplemental pain medication requests were tracked for analgesic groups as a measure of inadequate pain control.

Results: In the breast reduction group, the mean difference in PROMIS scores between multimodal (57.29) and narcotic (56.24) groups was 1.05 (95% CI, -2.81-4.91), below the minimal clinically meaningful difference of 10 points. For tissue expander placement, the mean difference was -2.76 (95% CI, -8.73-3.21). No significant differences were found in supplemental medication requests between groups for either procedure (P > .05).

Conclusions: Multimodal analgesia provides pain control comparable to traditional narcotic regimens in breast procedures. This approach may reduce opioid exposure with comparable patient-reported outcomes, supporting multimodal analgesic protocols as a strategy to mitigate opioid use in plastic surgery patients.

Introduction

Postoperative pain management is a cornerstone of patient care in plastic surgery, particularly in breast reduction and breast tissue expander placement following mastectomy. Opioid analgesics have been commonly used for managing postoperative pain. However, the risks associated with opioid use, including prolonged postoperative opioid dependence, chronic opioid use, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and associated complications, have necessitated the exploration of alternative strategies.1

The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society was formed in 2001 to promote the standardization of multispecialty practices based on evidence-based literature aiming to improve patient recovery after major surgery.2 Over the years, protocols have been developed in different surgical subspecialties.3-7 However, these ERAS protocols often incorporate many aspects of perioperative care that may not be directly associated with pain for outpatient surgery. Several documented protocols in other specialties involve the use of multidisciplinary specialties to optimize diet, nutrition, and physical therapy.

Multimodal analgesia, which employs a combination of non-opioid medications and different types of nerve blocks, has gained attention for its potential to improve pain control while minimizing opioid consumption.8 Although multimodal analgesic regimens have been explored in aesthetic and reconstructive plastic surgery, comparative data on their effectiveness relative to traditional narcotic regimens as well as patient-reported outcomes in pain improvement remain limited.9-12

This study evaluates the noninferiority of multimodal analgesia to narcotic regimens in breast reduction and tissue expander placement surgeries using patient-reported outcomes for pain control. We hypothesize that multimodal analgesic therapy is noninferior to traditional narcotic medications when provided in the postoperative setting. Our secondary hypothesis is that there would not be a significant difference between narcotic and multimodal analgesic groups in prescription refill requests.

Methods and Materials

Study design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at a single tertiary academic medical center. We obtained approval for our research protocol from our local institutional review board. This study and manuscript adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement for cohort studies. The study included patients who underwent bilateral breast reduction mammoplasty and tissue expander placement following mastectomy between January 2018 and December 2022.

Patient selection

Patients were categorized into 2 groups based on the prescribing patterns of their plastic surgeons (Figure 1). In the multimodal analgesia group, patients received a 1-time dose of acetaminophen 1000 mg preoperatively, followed by a postoperative prescription of tramadol 50 mg every 6 hours as needed and gabapentin 300 mg 3 times daily. In the narcotic analgesia group, patients received a prescription for only hydrocodone-acetaminophen 5 to 325 mg every 6 hours as needed postoperatively.

Figure 1: Inclusion criteria of breast patients undergoing breast tissue expander and breast reduction, subsequently stratified by postoperative analgesic group.

All patients undergoing mastectomy with tissue expander placement received pectoralis 1 and 2 fascial plane blocks performed by the oncologic breast surgeon following mastectomy and prior to expander placement.13 Patients received 30 mL 0.25% bupivacaine per side.

Perioperative medications were not controlled and were administered based on the preferences of the anesthesia provider. Inclusion criteria encompassed adult patients (≥ 18 years old) who underwent the specified procedures and completed the survey at the first postoperative visit (within 2 weeks). Oncoplastic reduction procedures were also included and grouped in the breast reduction population. Exclusion criteria included patients with preexisting chronic pain, chronic or preexisting opioid use, or incomplete pain assessment data. Direct-to-implant reconstruction and coinciding autologous breast flaps were also excluded from the tissue expander category. Study size was based on the time frame at which data was collected for the repository.

Pain intensity assessment

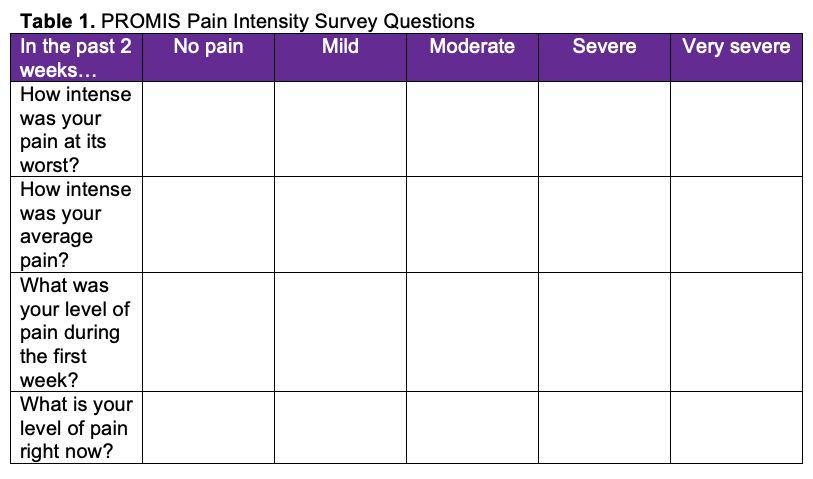

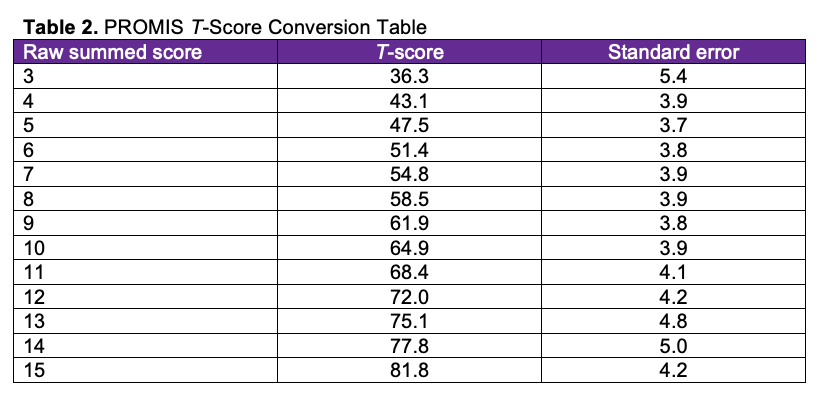

Postoperative pain intensity was measured using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pain intensity survey. The PROMIS initiative was created in 2004 to establish a resource for precise and efficient measurement of patient-reported symptoms and quality of life.14 Scores were collected at the first 2-week postoperative visit. The PROMIS Pain Intensity – Short Form 3a consisted of 3 questions, each with a score rating out of 5. An additional question was also provided to recall pain scores at week 1. Table 1 demonstrates a copy of the survey with the listed questions; Table 2 demonstrates the T-score conversion.

PROMIS pain intensity raw scores range from 3 to 15. Two raw scores were calculated based on the summation of questions 1, 2, and 3 and 1, 2, and 4. These raw scores were then converted to a T-score, as provided on the PROMIS scoring manual, with higher scores indicating greater pain. Potential areas of bias were mitigated by providing the survey only at the first postoperative visit at 2 weeks. Patients undergoing these procedures were compliant with follow-up; however, if there was a lack of follow-up and/or if there if was not a completed survey, those patients were excluded from the study.

Supplemental pain medication request/refill

Patient requests for additional pain medications were also tracked within the first 2 weeks following surgery. This included phone calls made by the patient and also in-person office visits. The type of medication that was filled was documented, including whether narcotics were prescribed.

Statistical analysis

A noninferiority test was utilized to compare pain intensity scores between the narcotic and multimodal analgesic groups for both breast reduction patients and tissue expander patients. The mean difference of PROMIS scores at 2 weeks with the CI set to 95% was determined. The mean difference of PROMIS scores between groups was analyzed to determine clinical significance, with a threshold of 10 points indicating meaningful clinical differences. Similarly, the mean difference of PROMIS scores at 1 week with 95% CI was used to compare the week 1 pain recall. A threshold of 1 point indicated a clinically meaningful difference.

Before retrospective data collection, a power analysis was performed for the primary outcome: PROMIS pain intensity scores at the first 2-week visit. As such, the noninferiority power analysis assumed an SD of 10 and a noninferiority limit of 10, resulting in a minimal total sample size of 26 (13 patients per group).

Chi-square test was used to compare the frequency of patients requesting pain medication refills between the narcotic and multimodal groups. Significance was set to a P-value of less than .05.

Results

Patient demographics

A total of 171 patients were included in the study and were divided into 2 groups based on the type of surgery performed: breast reduction (n = 107) and breast tissue expander placement (n = 64). Among breast reduction patients, 49 were assigned to the multimodal analgesia group and 58 to the narcotic group. In the tissue expander group, 19 patients received multimodal analgesia and 45 were treated with narcotics. Baseline demographics, including age, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities, were comparable across groups. All patients met the inclusion criteria of no prior history of chronic opioid or long-term pain medication use.

Pain intensity outcomes

The PROMIS pain intensity scores were used to evaluate the efficacy of multimodal and narcotic analgesia regimens in managing postoperative pain.

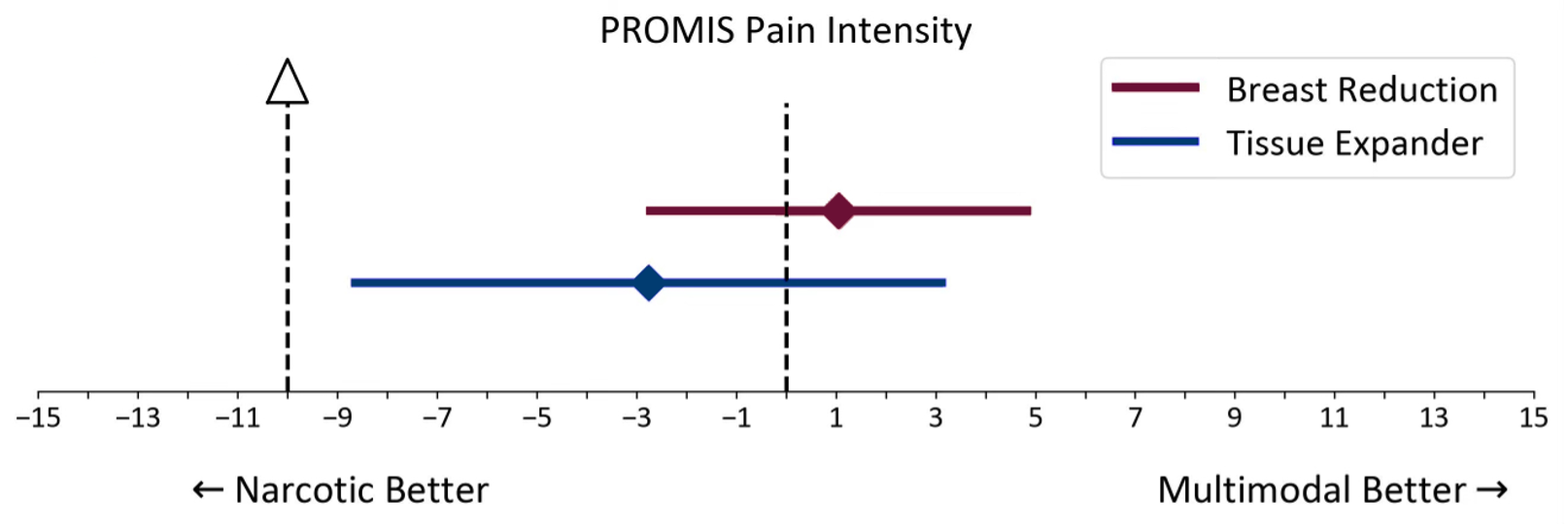

Breast reduction group. In the breast reduction group, the average PROMIS score was 57.29 for patients in the multimodal analgesia group and 56.24 for those in the narcotic group. The mean difference between groups was 1.05 (95% CI, -2.81-4.91), which was well below the minimal clinically meaningful difference of 10 points (Figure 2). This confirmed that the multimodal analgesia regimen was noninferior to the narcotic regimen for pain control.

Figure 2: PROMIS Pain Intensity Noninferiority Test of breast reduction and tissue expander groups.

Tissue expander placement group. In the tissue expander placement group, the average PROMIS score was 58.54 for patients in the multimodal analgesia group and 61.30 for patients in the narcotic group. The mean difference was -2.76 (95% CI, -8.73-3.21) (Figure 2). Similarly, the difference was below the minimal clinically meaningful threshold, supporting the noninferiority of multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain control in this patient population.

Pain recall

The PROMIS pain intensity scores were used to evaluate pain recall at week 1 for multimodal and narcotic analgesia regimens in managing postoperative pain.

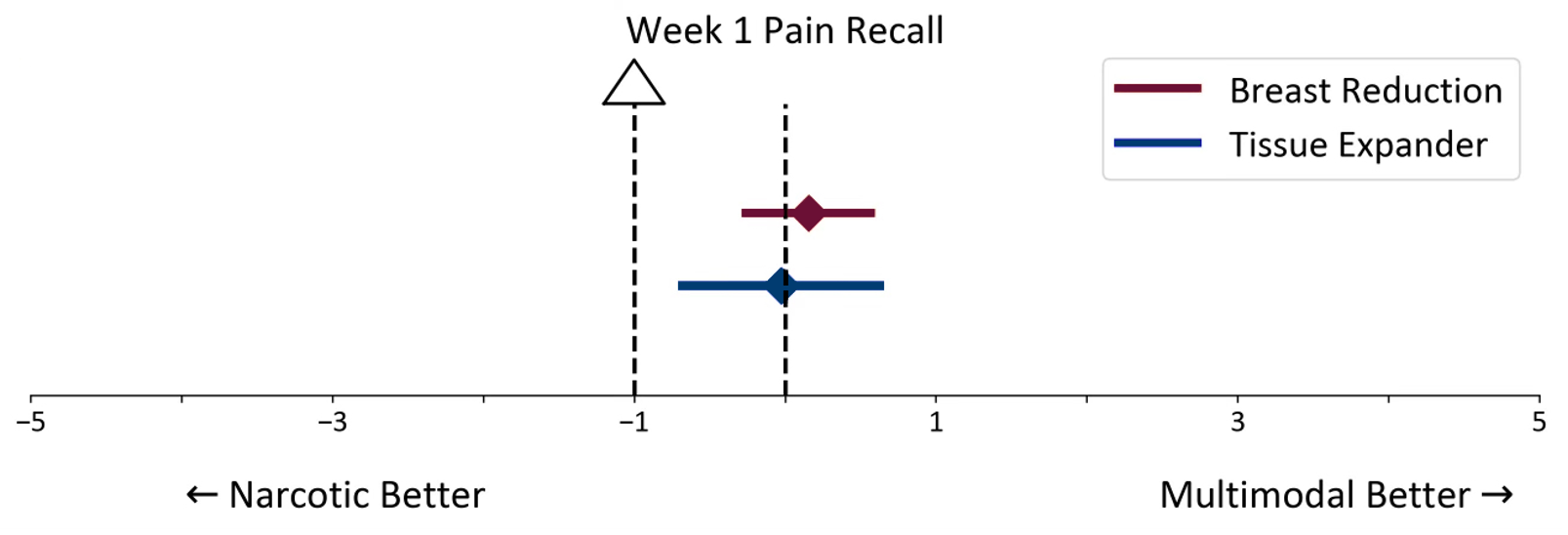

Breast reduction group. The mean difference between groups was 0.16 (95% CI, -0.29-0.60), which was below the minimal clinically meaningful difference of 1 point (Figure 3). This confirmed that the multimodal analgesia regimen was noninferior to the narcotic regimen for pain control at week 1 recall.

Figure 3: PROMIS Pain Recall Noninferiority Test at week 1 for breast reduction and tissue expander groups.

Tissue expander placement group. The mean difference was 0.03 (95% CI, -0.71-0.66) (Figure 3). Similarly, the difference was below the minimal clinically meaningful threshold, supporting the noninferiority of multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain control at week 1 recall.

Requests for supplemental pain medications

Analysis of supplemental pain medication requests provided further insight into the efficacy of each regimen.

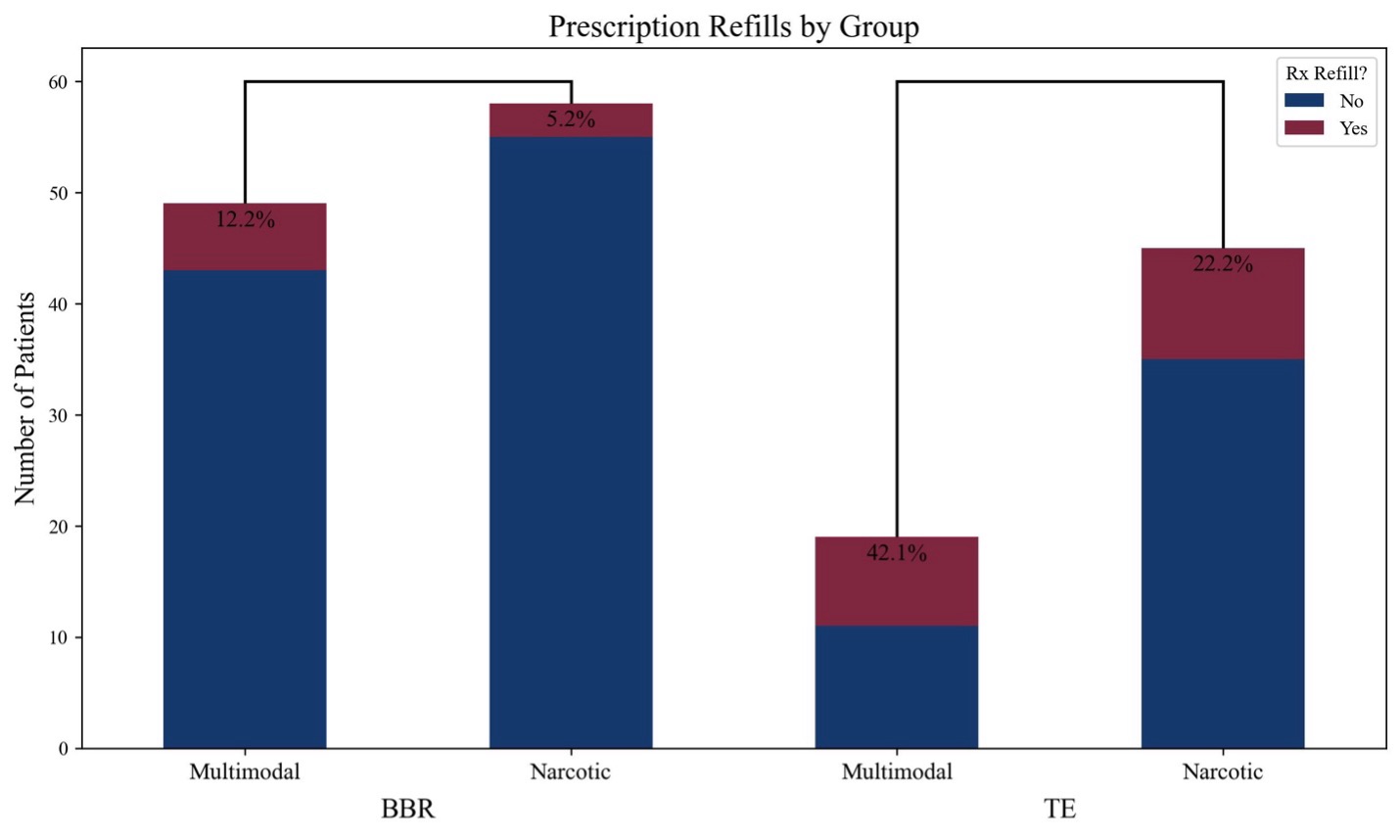

Breast reduction group. Among patients undergoing breast reduction, 6 out of 49 (12.2%) patients in the multimodal group requested additional medications, compared with 3 out of 58 (5.2%) patients in the narcotic group. In the multimodal group, 5 patients were prescribed narcotics, and 1 patient was prescribed a muscle relaxant. In the narcotic group, 2 patients received narcotic refills, and 1 patient was prescribed an NSAID. Chi-square test did not reveal a significant difference in the frequency of supplemental medication requests between the multimodal and narcotic groups (P = .335). Figure 4 demonstrates prescription refill frequency by group.

Figure 4: Chi-squared test comparing multimodal analgesic groups with narcotic analgesic groups in prescription refill rates. BBR = breast reduction; TE = tissue expander.

Tissue expander placement group. In the tissue expander group, 8 out of 19 (42.1%) patients in the multimodal group requested additional medications, compared with 9 out of 45 (20.0%) patients in the narcotic group. Among the multimodal group, 3 patients received narcotic prescriptions, 4 received refills of tramadol or gabapentin, and 1 was prescribed a muscle relaxant. In the narcotic group, 6 patients received narcotic refills, 1 was prescribed a benzodiazepine, and 2 were prescribed muscle relaxants. Chi-square test did not reveal a statistically significant difference between groups in the rate of additional medication requests (P = .189). Figure 4 demonstrates the prescription refill frequency by group.

Discussion

While there are several ERAS protocols available for breast reconstruction and other plastic surgery subspecialties, they can be highly variable in implementation and concentrate heavily in perioperative nutritional optimization and inpatient recovery.11,15,16 There is currently limited knowledge on the efficacy of multimodal analgesic regimen with regards to the patient perspective.

This study demonstrates that multimodal analgesia is noninferior to traditional narcotic regimens for managing postoperative pain in breast reduction and tissue expander placement surgeries, as measured by PROMIS pain intensity scores at 2 weeks postoperative and with pain recall at week 1.

The noninferiority of multimodal analgesia suggests that this regimen, consisting of preoperative acetaminophen and postoperative tramadol and gabapentin, is a viable alternative to narcotics for postoperative pain control. Patients in the multimodal group reported comparable pain scores to those in the narcotic group, with no clinically meaningful differences observed in either surgical cohort.

The analysis of supplemental pain medication requests provided additional insights into the effectiveness of each analgesia regimen. In the breast reduction group, there was no significant difference between the multimodal and narcotic analgesic groups for prescription refill. A similar trend was observed in the tissue expander group, where there was no significant difference between the 2 groups for prescription refill. The differences in the types of medications filled may be due to surgeon preference or on-call provider preference. It is important to note that 2 of the surgeons in the narcotic group performing tissue expander placements routinely prescribe benzodiazepines along with a narcotic for postoperative pain management and muscle relaxant.

Based on prior studies on opioid prescription patterns, postoperative opioid tablets often go unused.17-19 This results in a significant amount of leftover tablets per operation. Studies have similarly shown that by decreasing the quantity of opioid tablets dispensed, opioid consumption proportionately decreases without impacting postoperative pain control.20 In a similar fashion, demonstrating to the patient that narcotic medications are not necessary to achieve pain control using a noninferior regimen creates a mindset that is less dependent on opioids for postoperative pain relief.

The findings of this study have significant implications for clinical practice. Multimodal analgesia offers a safer alternative to narcotics, reducing the risk of opioid dependence and associated side effects. We have found that there were equivocal rates of supplemental medication refill either by phone or during clinic visit for both analgesic groups. Therefore, we conclude that the multimodal analgesic regimen and the quantity prescribed is noninferior to the traditional narcotic regimen.

This study further expands on the previous work by Faulkner et al capturing prospective data on patient-reported outcomes with 2 different analgesic regimens.9 By tracking prescription medication refill requests, this study was able to obtain further details on other medications that may have been prescribed by on-call providers, whether it be a narcotic, muscle relaxant, or another analgesic.

This study’s retrospective design introduces potential biases, including recall bias in patient-reported outcomes and variability in intraoperative anesthetic protocols. Additionally, some patients in the narcotic group received benzodiazepines postoperatively, which may have influenced their pain management outcomes.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that multimodal analgesia provides pain control comparable to traditional narcotic regimens in breast reduction and tissue expander placement procedures. While no significant differences in pain intensity were observed, the adoption of multimodal analgesia may reduce opioid exposure without compromising patient-reported pain outcomes. These results support the implementation of multimodal analgesic protocols as a strategy to mitigate opioid use in plastic surgery patients. Future prospective studies are needed to validate these findings, assess long-term outcomes

Acknowledgments

Authors: Waylon Zeng, MD; Nicholas Peterman, MD; Audrey Korte, BS; Morgan Parker, BS; Anthony Capito, MD

Affiliation: Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Section of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Roanoke, Virginia

Correspondence: Anthony Capito, MD, Section of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Carilion Clinic, 1906 Belleview Ave SE, Roanoke, VA 24014, USA. Email: aecapito@carilionclinic.org, phone number: +1 (540) 613-3880

Ethics: IRB number: 21-1360. All patients consented to the use of the survey data for research purposes.

Funding: None

Conflicts of interest: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.