Care Partner Perceptions of Patient Care in Postacute Rehabilitation Facilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

This study explored how care partners of patients with dementia perceived the care that their loved ones received in postacute rehabilitation (PAR) amid COVID-19-related visitor restrictions. Using a retrospective cohort design, researchers surveyed care partners of 53 patients (mean age, 82.9) discharged to 29 skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) between March 2020 and March 2021. Nearly all respondents (90.4%) reported visitor restrictions. Following their SNF stay, less than half of the patients returned to their prior living environment, while 23% were newly institutionalized. Most care partners surveyed reported an iatrogenic loss of mobility and functional status of their loved one, nearly two-thirds reported weight loss, and more than half reported worsened mood and memory. These findings suggest that while visitor restrictions aimed to protect vulnerable older adults residing in SNFs, they may have inadvertently caused iatrogenic harm to patients with dementia. The study underscores the need for future.

Citation: Ann Longterm Care. 2025. Published online October 21, 2025.

DOI:10.25270/altc.2025.11.005

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing homes were particularly hard hit. Nursing homes served as a nidus for infections, and residents experienced higher rates of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality compared with age-matched community-dwelling peers.1 To protect both staff and residents of residential and medical facilities, strict visitor restrictions were implemented. An emerging body of literature has begun to examine the impact of these restrictions. For example, a survey of nursing home staff and administrators early in the pandemic raised concerns that isolation affected residents’ motivation to participate in rehabilitation.2 Subsequent international studies demonstrated declines in cognition, physical ability, and communication, and increased loneliness among long-term care residents compared with their community-dwelling peers.3-5 Similarly, studies have suggested that family and caregivers were also adversely affected by visitor restrictions, with reports of increased sadness and anxiety among families of patients in intensive care settings, increased strain among families of patients in long-term residential care, and overall more distress than their hospitalized loved ones.6-8 However, less is known about the impact of visitor restrictions on patients’ experiences with postacute rehabilitation (PAR) in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs).

Older adults with cognitive impairment may have been particularly vulnerable to the consequences of visitor restrictions. One-third of all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries receiving PAR have a diagnosis of dementia, and these individuals are almost twice as likely to receive PAR care in an SNF than at home, despite similar outcomes within each setting.9,10 Patients with mild to moderate dementia benefit from PAR, although absolute functional recovery may be lower compared with older adults who are cognitively intact.11 Patients with dementia, however, often rely on advocates to help manage their care. Without reminders, patients with dementia may not properly use call lights, independently mobilize, take as-needed medications to properly control pain, or do other similar activities that require executive functioning. Patients with dementia may also require more assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), such as eating and bathing. Yet nursing homes were critically understaffed during the peak

Methods

Patient Population

Eligible participants were admitted to our institution (a quaternary care, academic medical center) and discharged to an SNF for PAR between March 1, 2020, and March 1, 2021. This period was chosen to coincide with the height of the COVID-19 pandemic-associated visitor restrictions. Patients were included in the study if they had a diagnosis of dementia, received a geriatric medicine inpatient consult during the hospitalization that led to SNF admission, and were aged 60 years or older at the time of the consultation. Dementia diagnosis was determined by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth revisions (ICD-9 and ICD-10) using a previously published identification tool; diagnoses of prion disease (neurodegenerative diseases secondary to misfolded proteins, such as Creutzfeldt-Jacon Disease) and normal pressure hydrocephalus without cognitive impairment were excluded.12 For eligible patients admitted and discharged to an SNF more than once within the study period, the latest chronologic experience was investigated.

Care partners listed as the principal contact in the electronic medical record were invited via telephone to participate in a short survey by one of two study team members (CR or LD). If these care partners did not answer the call, a brief, deidentified (when possible) voicemail was left that requested a callback, and follow-up calls were attempted. We used a standardized survey to inquire about the participants’ PAR stay, including length of stay, discharge destination following PAR, and whether visitor restrictions were in place. We then assessed the care partner respondents’ attitudes and perceptions of the care their loved one received and its impact across a series of domains to elicit changes in weight, memory, mood, mobility and functional status, stratified by performance of ADLs and instrumental ADLs (iADLS). Care partner respondents were advised that they could skip any questions they preferred not to answer. Survey responses were recorded in a secure REDCap database and paired with the patient’s deidentified clinical and demographic data. This study was reviewed and received approval from University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM00208812), and the study adhered to STROBE reporter guidelines for observational studies (https://www.strobe-statement.org/).

Results

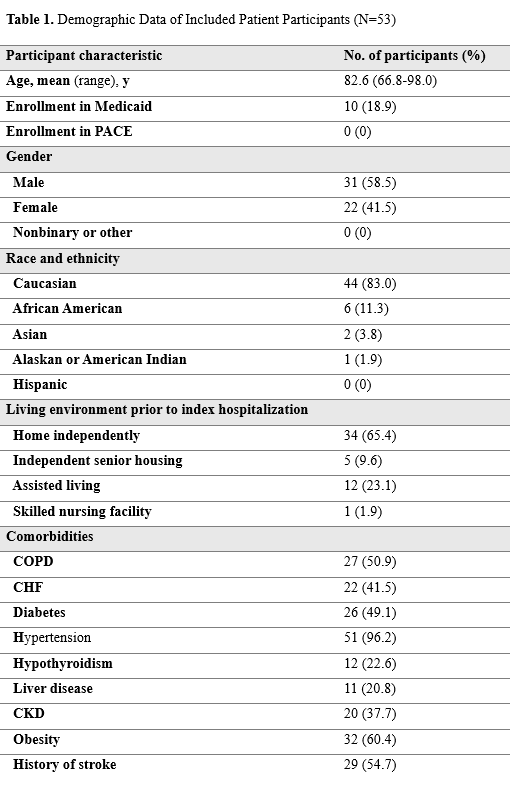

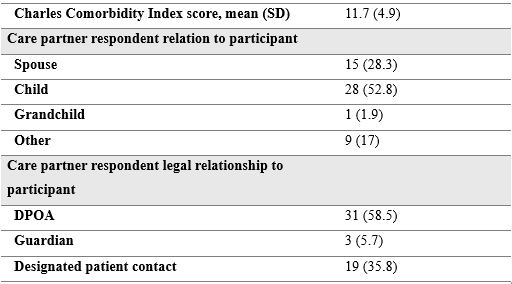

We identified 124 eligible patients. We were unable to reach 65 care partners (52.4%) due to outdated contact information or unanswered calls. Of the 59 (47.6%) care partners we contacted, 53 (89.8%) agreed to participate. The 53 patient participants were discharged from their index hospitalizations to 29 different SNFs. Length of stay in PAR varied: 15 (30.6%) patients stayed at PAR for 2 weeks or less, 17 (34.7%) stayed for 2 to 4 weeks, 10 (20.4%) stayed between 1 to 3 months, and seven (14.3%) participants stayed at PAR for longer than 3 months. Table 1 summarizes demographic data of the included patient participants and the relationships of their care partner respondents.

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DPOA, durable power of attorney; PACE, Program for All-Inclusive Care of the Elderly.

Forty-seven care partner respondents (90.4%) reported visitor restrictions during the rehabilitation stay, three (5.6%) reported no restrictions, two (3.7%) were uncertain if there were restrictions, with one missing response. Nineteen (35.8%) care partner respondents reported they were allowed limited in-person visits, 26 (49.1%) reported visitations through the window, and three (5.6%) were not allowed any visitation. A small number of care partner respondents reported multiple types of restrictions, likely reflecting changing policies over the course of the PAR stay.

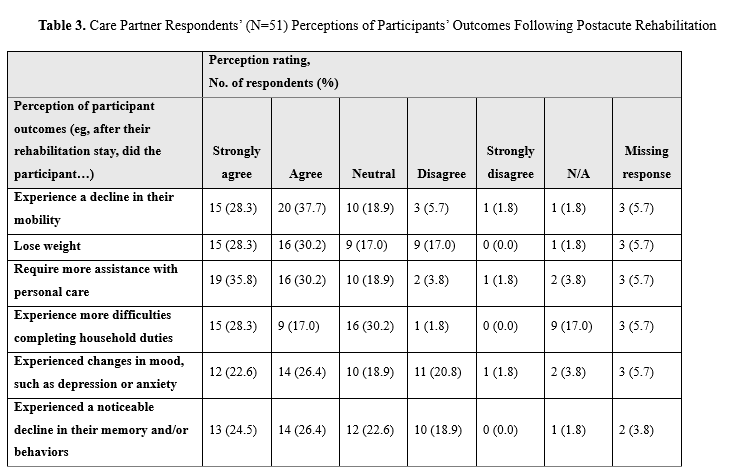

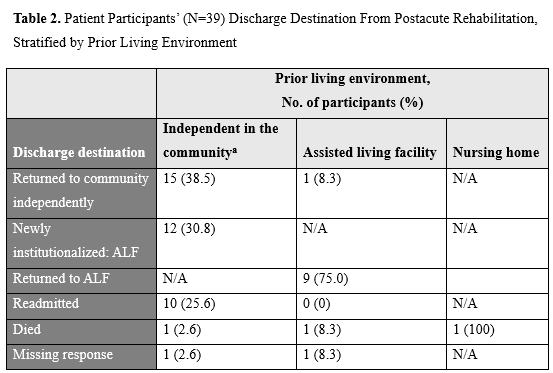

Table 2 summarizes discharge destination from participants’ SNF stay, stratified by living environment prior to index hospitalization. Table 3 summarizes care partner respondents’ answers to the survey questions. We stratified the responses of care partner respondents who exclusively reported that they were limited to window visits (n = 22) vs those who exclusively experienced limited in-person visits (n = 15), to assess whether responses differed. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding weight, memory, mood, mobility, or performance of iADLs. However, care partner respondents limited to window visits reported a greater decline in their loved ones’ performance of ADLs compared with those who were allowed in-person visitation (P = .02).

Abbreviations: ALF, assisted living facility; N/A, not applicable.

aLiving independently in the community includes participants who lived at home or in independent senior housing.

Discussion

People living with dementia represent a vulnerable population who often rely on caregivers to navigate the complex health care systems and advocate for their needs. Dementia presents several potential barriers to successful rehabilitation, including a higher risk of delirium, which may persist in the postacute setting and is associated with negative outcomes.13 Cognitive impairment may also impede patients’ ability to engage with and retain information from therapists. Given the large patient-to-nurse ratios at many PAR facilities, patients who cannot request “as-needed” medications or properly use call devices may experience unmet needs. Nonetheless, studies show that patients with dementia can and do benefit from PAR, particularly those with earlier stages of disease.11,14,15

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, health care facilities implemented strict visitor restrictions, raising significant concerns for older adults with cognitive impairment.16 This study explores the perceptions of care partners of those living with dementia and demonstrates concerningly negative results. Most of the surveyed care partner respondents reported that their loved one lost mobility and functional abilities following incident hospitalization and PAR. Nearly two-thirds of care partner respondents reported that their loved one experienced weight loss, and more than half reported both diminished mood and memory. Window visits were associated with a greater decline in performance of ADLs compared with limited in-person visits.

Objectively, less than half of participants returned to their prior living environment after discharge. Rates of readmission and mortality are similar to those previous reports.10,17 There are limited data regarding rates of institutionalization following PAR. In a large study comprising more than 500 000 Medicare beneficiaries, 10% of the population who were alive 6 months after the incident hospitalization entered long-term care.18 In our study, 23% of participants newly entered long-term care after PAR, representing more than double the previously reported rate. This high rate of entry into long-term care corroborates the significant decline in functional and cognitive status reported by care partner respondents.

This study has several limitations. It was conducted at a single academic institution and included a relatively small number of care partner respondents, although the response rate among those reached was very high. Outcome data were obtained from care partner respondents and not corroborated by the patients themselves, so there is likely some degree of self-response and recall biases. The small sample size does not allow us to stratify data based on such factors as dementia severity or the SNF to which patients were discharged. Despite these limitations, we believe this study provides critical insights on families’ perceptions of visitor restrictions in PAR facilities.

Following hospitalization, rehabilitation is meant to improve patient’s functional status such that they can achieve their prior level of functioning. This study overwhelmingly demonstrates perceived decline in cognitive and physical functioning in patients with dementia who were sent to PAR facilities at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although visitor restrictions were implemented to keep patients safe, they may have imparted real harm on vulnerable older adults. This study contributes to the expanding body of evidence indicating that visitor restrictions during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic may have led to iatrogenic harms.6-8,19

Conclusion

Although PAR is often a place for healing and recovery, care partners in our study perceived their loved ones’ PAR experiences as detrimental. Their perception is supported by high rates of post discharge institutionalization. While we hope that the COVID-19 pandemic remains a singular event within our lifetime, should another pandemic occur, future policies must consider the impact that isolation can have on patients who are unable to advocate for themselves. More research is needed to identify policies that protect PAR staff and providers without compromising patients’ recovery.

Authors: Kahli Zietlow, MD1 • Neil Nixdorff, MD1 • Leslie Dubin, MSW2 • Chad Roath, NP1 • Shenbagam Dewar, MD1,3

Affiliations:

1Division of Geriatric and Palliative Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

2Department of Social Work, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

3Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, MI

Disclosures: This research did not receive any funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. However, one author receives partial salary support from the Health Resources and Services Administration via grant 1 K01HP49055‐01‐00. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Address correspondence to:

Kahli Zietlow, MD

Internal Medicine – GPM

300 North Ingalls Bldg., Room 907

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

Phone: (734)-764-9319

Email: Kaheliza@med.umich.edu

References

- Cronin CJ, Evans WN. Nursing home quality, COVID-19 deaths, and excess mortality. J Health Econ. 2022;82:102592. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2022.102592

- Reddy A, Resnik L, Freburger J, et al. Rapid changes in the provision of rehabilitation care in post-acute and long-term care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(11):2240-2244. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2021.08.022

- Battams S, Martini A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with cognitive impairment residing in aged care facilities: an integrative review. Inquiry. 2023;60:469580231160898. doi:10.1177/00469580231160898

- Eriksson E, Hjelm K. Residents' experiences of encounters with staff and communication in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative interview study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):957. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03627-x

- Huber A, Seifert A. Retrospective feelings of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic among residents of long-term care facilities. Aging Health Res. 2022;2(1):100053. doi:10.1016/j.ahr.2022.100053

- Suh J, Na S, Jung S, et al. Family caregivers' responses to a visitation restriction policy at a Korean surgical intensive care unit before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Heart Lung. 2023;57:59-64. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.08.015

- Cornally N, Kilty C, Buckley C, et al. The experience of COVID-19 visitor restrictions among families of people living in long-term residential care facilities during the first wave of the pandemic in Ireland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(11):6559. doi:10.3390/ijerph19116559

- Felser S, Sewtz C, Kriesen U, et al. Relatives experience more psychological distress due to COVID-19 pandemic-related visitation restrictions than in-patients. Front Public Health. 2022;10:862978. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.862978

- Burke RE, Xu Y, Ritter AZ. Use of post-acute care by Medicare beneficiaries with a diagnosis of dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(5):877-879.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2021.09.016

- Burke RE, Xu Y, Ritter AZ, Werner RM. Postacute care outcomes in home health or skilled nursing facilities in patients with a diagnosis of dementia. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(3):497-504. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13855

- Allen J, Koziak A, Buddingh S, Liang J, Buckingham J, Beaupre LA. Rehabilitation in patients with dementia following hip fracture: a systematic review. Physiother Can. 2012;64(2):190‐201. doi:10.3138/ptc.2011-06BH

- Bush K, Wilkinson T, Schnier C, Nolan J, Sudlow C; UK Biobank Outcome Adjudication Group. Definitions of dementia and the major diagnostic pathologies, UK Biobank phase 1 outcomes adjudication. Accessed July 25, 2025. https ://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ukb/ukb/docs/alg_outcome_dementia.pdf

- Gual N, Morandi A, Pérez L, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of delirium in older patients admitted to postacute care with and without dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2018;45(1-2):121-129. doi:10.1159/000485794

- Seematter-Bagnoud L, Lécureux E, Rochat S, Monod S, Lenoble-Hoskovec C, Büla CJ. Predictors of functional recovery in patients admitted to geriatric postacute rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(12):2373-2380. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.06.024

- Seitz DP, Gill SS, Austin PC, et al. Rehabilitation of older adults with dementia after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):47-54. doi:10.1111/jgs.13881

- O’Hanlon S, Inouye SK. Delirium: a missing piece in the COVID-19 pandemic puzzle. Age Ageing. 2020;49(4):497-498. doi:10.1093/ageing/afaa094

- Werner RM, Coe NB, Qi M, Konetzka RT. Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home health care vs to a skilled nursing facility. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(5):617-623. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7998

- Middleton A, Li S, Kuo YF, Ottenbacher KJ, Goodwin JS. New institutionalization in long-term care after hospital discharge to skilled nursing facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):56-63. doi:10.1111/jgs.15131

- Iness AN, Abaricia JO, Sawadogo W, et al. The effect of hospital visitor policies on patients, their visitors, and health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2022:135(10):1158-1167.e3. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.04.005