The Use of an Acellular Wound Matrix for Mohs Surgical Reconstruction: A Case Series

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Malignancies of the foot are relatively rare and pose a problem for clinicians, with malignant melanoma in this area associated with poor prognosis. The foot has unique anatomy for weight bearing, and preserving this role is imperative; as such, smaller-than-recommended margins are often taken to preserve patient function. Objective. To evaluate the effectiveness of an acellular wound matrix for soft tissue reconstruction after Mohs surgical resection of soft tissue lesions in the foot. Materials and Methods. The records of 29 patients who underwent a Mohs surgical procedure from January 2018 to January 2023 were reviewed. The same surgeon performed all these surgeries. The average healing time, wound size, and complication rates were noted. Results. The average patient age was 61.3 years. Twelve of the subjects were male (41.4%) and 17 were female (58.6%). Nineteen (65.5%) of the lesions were diagnosed as melanoma, and 10 lesions (34.5%) were located on the toe. The average wound size after surgical resection was 4.4 cm × 4.0 cm × 0.8 cm. Twenty-two patients healed (75.9%). The average (SD) wound healing time was 139 (90.8) days. Eight patients (27.6%) had postoperative complications. Conclusion. Using an acellular wound matrix after Mohs surgical resection of soft tissue lesions in the foot is a viable option. Patients functioned well after healing. Complication rates are higher in the foot than in other areas of the body using this protocol. Good surgical technique and strong knowledge of the anatomy of the foot and ankle are needed to prevent and manage these complications.

The foot accounts for approximately 3% to 15% of all reported cases of cutaneous melanoma.1,2 Malignancies of the foot are relatively rare and pose a difficult problem for clinicians, with malignant melanoma in this area associated with poor prognosis.1,3 The foot has unique anatomy for weight bearing, and preserving this distinctive role is imperative to patient function after any intervention. To surgically resect a melanoma lesion on the foot, smaller-than-recommended margins of soft tissue are taken to avoid amputation and preserve function compared with other areas of the body. However, the use of smaller margins increases the risk for recurrence and healing complications. Additionally, because in the foot there is little soft tissue over deep structures, large deficits with exposed deep structures are at risk with any surgical resection of lesions of the foot.

Surgical deficits can be resolved by a wide range of healing mechanisms, such as primary closure, secondary closure, autologous skin grafts, and local and free tissue flaps. Use of a bilayer acellular matrix made of cross-linked bovine type I collagen and chondroitin-6-sulfate (Integra Dermal Regeneration Template [DRT]; Integra LifeSciences) can give surgeons additional options to cover large soft tissue deficits by providing a matrix for cellular migration and rapid revascularization that can afford durable coverage of deep soft tissue structures and can reduce wound contracture.4-6 This ultimately leads to replacement of the biological tissue with native tissue through the healing process.6 Acellular dermal matrices have been used for a wide range of soft tissue traumas in the lower extremity, including burns, postoperative complications, and diabetic foot ulcerations.4 The advantages of DRT include immediate coverage during surgery, simple application, predictable reconstructive results, application over deep structures such as tendon and bone, and reasonable economic applications.7,8

One method for resection of cutaneous tumors is Mohs micrographic surgery, which is a specialized technique for the management of cutaneous cancers.9 A widely accepted standard technique, Mohs surgical resection involves removing thin layers of the skin lesion and surrounding tissue and examining each layer for abnormalities until all abnormal tissue is resected.9-11 Mohs procedures are ideal for areas with either minimal soft tissue or need for cosmetic consideration, such as the eyes, nose, and lips, because it can minimize the size of the wound and subsequent deformation.12 Most cutaneous tumor resections require some form of reconstructive treatment, even when minimal tissue is removed.12

In the foot, reconstruction of large soft tissue deficits is a complex undertaking given the limited soft tissue available for rearrangement. There is scant literature on the use of DRT after Mohs procedures in the foot for skin cancers, with only 1 review article and 2 single case reviews found by the authors of the current case series. This report presents a single-

surgeon case series evaluating the effectiveness of an acellular wound matrix for soft tissue reconstruction after Mohs surgical resection of soft tissue lesions of the foot.

Materials and Methods

This case series discusses patients who underwent a Mohs surgical procedure from January 2018 to January 2023. Medical records of patients were retrospectively reviewed. All Mohs procedures were performed by 1 surgeon (JFT). Patients 18 years or older were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they did not have a DRT placed at the surgical site or were not discharged from the clinic before January 2023, or if the lesion was located above the ankle. Institutional review board approval was not required because no patient-identifying information was recorded.

Age, sex, body mass index, medical comorbidities, smoking status, location of the lesion, type of lesion, date of Mohs surgery, date of DRT placement, date of epithelialization, wound size, adjunct procedures, complications, and long-term outcomes were collected for each patient. Vascular status was not assessed. Off-loading was achieved with the use of either negative pressure wound therapy and non–weight bearing, or a well-

padded posterior splint and weight bearing after 7 days of non–weight bearing. After delamination of the DRT, the surgical site was dressed with petrolatum-based fine mesh gauze containing 3% bismuth tribromophenate and an elastic bandage until healing was complete or split-thickness skin grafting (STSG) was performed. Each patient’s off-loading protocol was determined at the primary surgeon’s discretion (J.F.T.). Healing, defined as complete epithelialization, needed to be specifically stated at the patient’s follow-up appointment to be recorded. Data were recorded in a spreadsheet, and the average healing time, wound size, and follow-up were reported.

The surgical procedure and postoperative course were conducted by a single surgeon (J.F.T.), who followed a typical treatment algorithm. After resection of the skin cancer, DRT was immediately applied over the surface of the defect and sutured into place. Dressing over the DRT included negative pressure wound therapy or a dry dressing with splint, which was utilized at the discretion of the primary surgeon. When the neodermis (a vascularized wound bed) was formed, typically 4 weeks to 6 weeks later, the patient was returned to the operating room for application of an autologous STSG. The patient was then followed in the outpatient clinic until complete epithelialization occurred.

A pricing analysis was also performed for the current study based on medical self-pay pricing. The payment information for non–self-pay patients was not available for analysis. Price per office visit, each surgical intervention with anesthesia, and negative pressure wound therapy or dressing supply costs were obtained from hospital administration staff. This price was then compared with the average cost of melanoma treatment reported in the literature.

Results

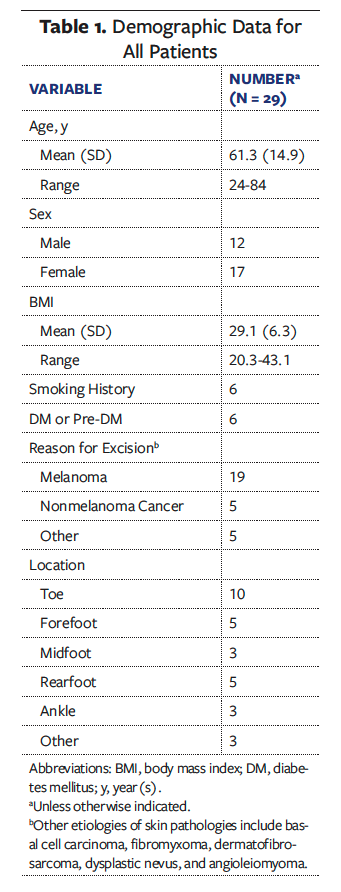

Twenty-nine patients were included in the analysis. The average (SD) patient age was 61.3 (14.9) years (range, 24 years-84 years). Twelve of the subjects were male (41.4%) and 17 were female (58.6%). Nineteen (65.5%) of the lesions were diagnosed as melanoma, and 10 lesions (34.5%) were located on the toe (Table 1).

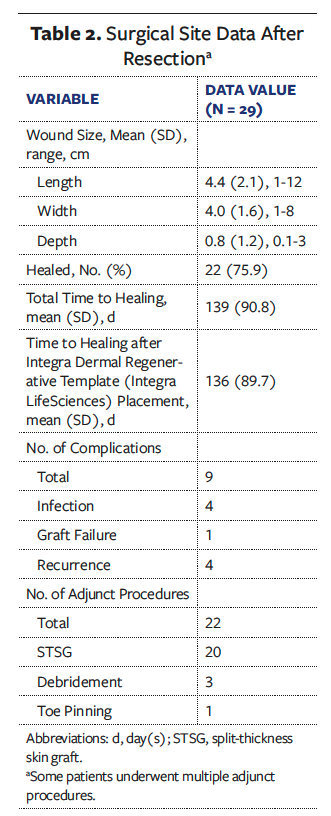

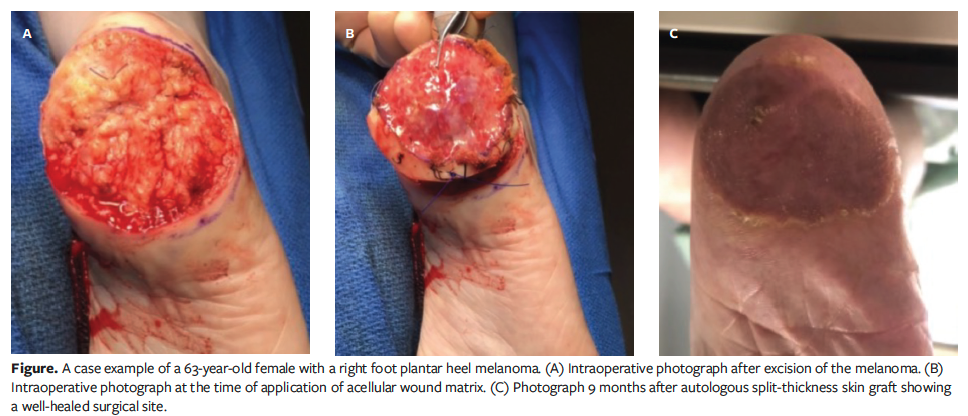

The average wound size after surgical resection was 4.4 cm × 4.0 cm × 0.8 cm (Table 2). Twenty-two (75.9%) of the patients were healed at an average of 140.8 days. The average (SD) wound healing time from the initial surgical intervention to complete healing after grafting and complete return to activities was 139 (90.8) days. Twenty-two total adjunct procedures were performed; 91.0% of the procedures were autologous STSGs. Eight patients (27.6%) had a total of 9 postoperative complications, including infection (n = 4 [13.8%]), recurrence (n = 4 [13.8%]), and matrix graft failure (n = 1 [3.4%]). No patient needed revision surgery. All patients with noted functional status postoperatively returned to preoperative functional levels. One patient reported pain, which was resolved before healing at final follow-up. The Figure shows a postoperative lesion, acellular matrix application, and final healing in 1 patient.

The pricing analysis was performed based on the medical facility’s reported patient self-pay rates. The office visit price was $270, and the estimated average number of office visits was 5. The Mohs surgical resection with anesthesia price was $13 450.99. The price for surgical application of the DRT was $10 530.09. If a staged procedure requiring additional anesthesia and preparation was required, the price was $12 435.84. The subsequent STSG procedure was $12 653.47. If a patient needed negative pressure wound therapy, the price for that was $986.40. The average total cost for dressings was $391.50. The average price for the entire treatment course per patient was estimated to be $39 362.45.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case series reporting the use of DRT for reconstruction after Mohs resection of cutaneous lesions of the foot and ankle. Overall, patients were noted to heal well after Mohs surgical resection and placement of DRT, with an average healing time of 140.8 days. While some shorter times have been noted in the diabetic foot literature with the use of DRTs, the average wound size reported in those studies was typically smaller than the average wound size in the present study. Additionally, in the current case series 5 patients did not undergo application of DRT on the same date of Mohs surgical resection, and 9 complications were noted. Several factors may contribute to the average healing time in the present study. The DRT was noted to be vital in decreasing wound size and creating a neodermis, allowing for secondary healing and adjunct procedures, including autologous STSG. All patients were noted to have returned to their preoperative function, and all pain was resolved at the completion of treatment. This demonstrates the reconstructive success of an acellular wound matrix in areas that are complicated by specific functional demands and unique anatomy for weight bearing.

Uses of acellular dermal matrix in the foot have been extensively studied in the literature. DRTs have been used on burn wounds as well as diabetic foot ulcerations, which are notoriously difficult to heal. Asif et al13 examined the use of an acellular matrix for a deep burn on the plantar aspect of the foot in a case study. While the study includes only 1 case, it demonstrates the use of DRT to cover deep structures of the foot. In a randomized controlled trial, Driver et al14 examined the use of DRT in 307 patients with nonhealing diabetic foot ulcerations. The treatment group had a statistically significantly higher and faster rate of healing with DRT than the control group. Hicks et al15 prospectively examined high-risk diabetic foot ulcerations treated with a DRT and found a 93% healed rate after 18 months of treatment. Finally, Kim et al16 created a retrospective registry using data from 4 academic institutions and compared DRT with multiple other advanced techniques (negative pressure wound therapy, local tissue flaps, free tissue transfers) for closure of complex wounds in complex patients. No statistically significant differences were found between any of the advanced treatment modalities for diabetic foot reconstruction in complex patients.16

While risks are still present for infection, fluid entrapment, and incorrect application with the use of acellular dermal matrix, the literature has supported its use in the foot for several etiologies and high-risk wounds. Grush et al17 examined the use of DRTs after Mohs surgeries in the lower extremity specifically in a review article with 3 cases. That review found biological skin substitutes to be a viable treatment option for these cases, especially given the unique functional demand placed on the lower extremity. In the 3 case studies, which examined deficits of the toe, heel, and posterior leg, DRT was applied after Mohs surgical resection. Two patients received STSG after DRT incorporation, and 1 required pinning of a digit. All patients recovered after treatment, and no complications were reported. However, that study was primarily focused on the literature review, and no statistical analysis of the cases was performed. Rodríguez-Lomba et al18 reported successful restoration of function and satisfactory aesthetic outcomes using DRT following surgical excision of acral melanoma on the plantar and lateral surface of the foot. Cunningham and Marks19 published a case study reporting restored functionality in a complex Mohs defect of the foot using DTR and STSG. Overall, literature findings showcase DTR’s potential to cover deep structures on the foot, allow for autografting, and preserve foot function after healing. While promising, the studies specifically examining DRT after Mohs surgical resection in the foot and ankle were limited to a single foot case or literature review. None reported complications. Because melanomas of the foot tend to have a poor prognosis and because the risk for exposing deep structures with surgical resection is high, the present study supports the use of DRTs in these clinical scenarios.

DRT and other types of cellular and/or tissue-based products (CTPs) have also been used after Mohs surgery in areas other than the foot. Lu and Khachemoune20 performed a systematic review of the use of CTPs after Mohs surgery. Forty studies with a total of 687 patients were included in that review; however, most studies were underpowered, and the majority of them were not comparative. The authors of that study concluded that the use of CTPs after Mohs surgical resection was not well studied and that more robust studies were needed. Other studies have advocated for the use of acellular matrices for Mohs reconstruction. Faibisof and Taupin12 examined the use of DRTs in the nose, an area with delicate neurovasculature and high cosmetic demand. They found that patients had better cosmetic outcomes and higher satisfaction after use of the bilayer skin substitute than with more traditional closure techniques. Improved cosmesis and increased patient satisfaction have also been reported after use of acellular dermal matrix for scalp and cheek reconstruction.21,22 Overall, the use of acellular dermal matrix in these studies—specifically MicroMatrix (Integra LifeSciences), Cytal Wound Matrix (Integra LifeSciences), or a DRT—for reconstruction after Mohs procedures has substantial support, resulting in good functionality and cosmetic appearance.

The complication rate in the current case series was 27.6%, with infection and recurrence the most common complications (13.8% each). Overall, the complication rate after Mohs surgery is thought to be relatively low,23 around 3% (range, 2.5%-5.4%), with the most common complication being surgical site infection.23-26 However, this rate varies depending on the area of the body. For example, the complication rate after Mohs surgery of the head and neck has been reported to be 8.2%.27 The complication rate after DRT use in various applications was found to be between 3.7% and 42%, with an average rate of 16.9% in a recent systematic review.28-30 The foot poses many challenges to the surgeon, which may explain the higher rates of infection and recurrence. The 27.6% complication rate in the present case series is comparable to the 32% complication rate reported by Gray et al,31 which specifically examined melanomas of the foot. With such delicate anatomy, preserving function in the foot often requires smaller-than-average margins during surgical lesion resection. These smaller margins could lead to inadequate resection of abnormal cells. The foot also has many skin folds and hard-to-clean areas, such as under toenails and in interspaces. This may lead to higher infection rates than reported overall for Mohs procedures. Good surgical technique and strong knowledge of the anatomy of the foot and ankle are needed to prevent and manage these complications.

As noted above, the patient pricing of the entire treatment course from initial office visit to complete healing was an estimated $39 362. While the cost of cancer treatment has increased, a recent study examining the cost of using immunotherapy for melanoma found that stage II melanoma (melanoma that had infiltrated deep tissue but did not travel to lymph nodes) cost an average of $40 823 (Canadian dollars).32 Other studies reported a total cost of surgical treatment of melanoma ranging from approximately $27 000 to $85 000.33-35 However, the most recent of these studies is over a decade old, and the data may not reflect the current medical care prices. Given the available information in the current literature, the pricing of the current study’s treatment protocol is similar to the average treatment for melanoma using other therapies. When functional preservation and soft tissue reconstruction are considered, the current treatment protocol is a favorable option for foot and ankle lesions.

Limitations

The current study has limitations. First, the case series is relatively small and has a low level of evidence. Second, there is no comparison group for other reconstructive options. Third, for many patients some information, such as functional assessment, was missing or was not obtained. Fourth, a selection bias may be present given the retrospective review of cases or the single surgeon’s decision to use a DRT vs other reconstructive options. Fifth, the long-term durability of DRT in this population remains unanswered because the patients were not prospectively tracked and thus were lost to follow-up. Larger, prospective, comparative studies are needed to determine a more reliable rate of recurrence and complications.

Conclusion

Using a DRT after Mohs surgical resection of soft tissue lesions is a viable option in the foot. Patients in the current series were able to function well after healing. Complication rates in the foot are noted to be higher than in other areas of the body using this protocol, which may be due to the anatomical and functional uniqueness of the foot. Good surgical technique and strong knowledge of the anatomy of the foot and ankle are needed to prevent and manage these complications

Author and Public Information

Authors: Elizabeth A. Ansert, DPM1; James F. Thornton, MD¹; Amy Du, BS2; Alexandra Thornton, BS3; and Paul J. Kim, DPM1

Affiliations: 1Department of Plastic Surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA; 2Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, USA; 3University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA

Disclosure: The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines.

Correspondence: Elizabeth A. Ansert, DPM; Thibodaux Regional Health System Foot and Ankle Center, 290 Bowie Rd, Thibodaux, LA 70301; elizabeth.ansert@thibodaux.com

Manuscript Accepted: September 2, 2025

References

1. Soong SJ, Shaw HM, Balch CM, McCarthy WH, Urist MM, Lee JY. Predicting survival and recurrence in localized melanoma: a multivariate approach. World J Surg. 1992;16(2):191-195. doi:10.1007/BF02071520

2. Tseng JF, Tanabe KK, Gadd MA, et al. Surgical management of primary cutaneous melanomas of the hands and feet. Ann Surg. 1997;225(5):544–553. doi:10.1097/00000658-199705000-00011

3. Rashid OM, Schaum JC, Wolfe LG, Brinster NK, Neifeld JP. Prognostic variables and surgical management of foot melanoma: review of a 25-year institutional experience. ISRN Dermatol. 2011:2011:384729. doi:10.5402/2011/384729

4. Kim PJ, Steinberg JS. A closer look at bioengineered alternative tissues. Podiatry Today. 2006;19(7):38-55.

5. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Steinberg JS, Evans KK. Integra® bilayer wound matrix application for complex lower extremity soft tissue reconstruction. Surg Technol Int. 2014;24:65-73.

6. Delgado-Miguel C, Miguel-Ferrero M, Muñoz-Serrano A, Díaz M, López-Gutiérrez JC, De la Torre C. The use of acellular dermal matrix (Integra Single Layer) for the correction of malformative chest wall deformities: first case series reported. Surgery J (N Y). 2022;8(3):e187-e191. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1755622

7. Voigt DW, Paul CN, Edwards P, Metz P. Economic study of collagen-glycosaminoglycan biodegradable matrix for chronic wounds. Wounds. 2006;18(1):1-7.

8. Dantzer E, Braye FM. Reconstructive surgery using an artificial dermis (Integra): results with 39 grafts. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54(8):659-664. doi:10.1054/bjps.2001.3684

9. Golda N, Hruza G. Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41(1):39-47. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.07.006

10. Wong E, Axibal E, Brown M. Mohs micrographic surgery. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019;27(1):15-34. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2018.08.002

11. Ng E. Mohs surgery. John Hopkins Medicine. Accessed September 4, 2023. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-

diseases/mohs-surgery

12. Faibisoff B, Taupin P. Use of collagen-glycosaminoglycan silicone bilayer matrix for closure of post-Mohs micrographic surgery defects on the nose: a 5-case series. Wounds. 2023;35(2):E90-E97. doi:10.25270/wnds/22054

13. Asif M, Ebrahim S, Major M, Caffrey J. The use of IntegraTM as a novel technique in deep burn foot management. JPRAS Open. 2018;17:15-20. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2018.04.003

14. Driver VR, Lavery LA, Reyzelman AM, et al. A clinical trial of Integra template for diabetic foot ulcer treatment. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(6):891-900. doi:10.1111/wrr.12357

15. Hicks CW, Zhang GQ, Canner JK, et al. Outcomes and predictors of wound healing among patients with complex diabetic foot wounds treated with a dermal regeneration template (Integra). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146(4):893-902. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000007166

16. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Orgill D, et al. Complex lower extremity wound in the complex host: results from a multicenter registry. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7(4):e2129. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002129

17. Grush AE, Depani M, Parham MJ, Mejia-

Martinez V, Thornton A, Sammer DM. Use of biologic agents in extremity reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg. 2022;36(1):43-47. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1744282

18. Rodríguez-Lomba E, Lozano-Masdemont B, Sánchez-Herrero A, Avilés-Izquierdo JA. Dermal substitutes: an alternative for the reconstruction of large full-thickness defects in the plantar surface. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96(6):717–720. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.08.026

19. Cunningham T, Marks M. Vacuum-

assisted closure device and skin substitutes for complex Mohs defects. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40 Suppl 9:S120–S126. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000113

20. Lu KW, Khachemoune A. Skin substitutes for the management of mohs micrographic surgery wounds: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(1):17-31. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02327-1

21. Depani M, Ferry AM, Grush AE, Moreno TA, Jones LM, Thornton JF. Use of biologic agents for lip and cheek reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg. 2021;36(1):26-32. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1741399

22. Harirah M, Sanniec K, Yates T, Harirah O, Thornton JF. Scalp reconstruction after Mohs cancer excision: lessons learned from more than 900 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2021;147(5):1165-1175. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000007884

23. DelMauro MA, Kalberer DC, Rodgers IR. Infection prophylaxis in periorbital Mohs surgery and reconstruction: a review and update to recommendations. Surv Ophthalmol. 2020;65(3):323-347. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.12.001

24. Snow SN, Stiff MA, Bullen R, Mohs FE, Chao WH. Second-intention healing of exposed facial-scalp bone after Mohs surgery for skin cancer: review of ninety-one cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(3 Pt 1):450-454. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70209-8

25. Merritt BG, Lee NY, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA, Cook J. The safety of Mohs surgery: a prospective multicenter cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(6):1302-1309. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.05.041

26. Basu P, Goldenberg A, Cowan N, Eilers R, Hau J, Jiang SIB. A 4-year retrospective assessment of postoperative complications in immunosuppressed patients following Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1594-1601. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.032

27. Patel SA, Liu JJ, Murakami CS, Berg D, Akkina SR, Bhrany AD. Complication rates in delayed reconstruction of the head and neck after Mohs micrographic surgery. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016;18(5):340-346. doi:10.1001/jamafacial.2016.0363

28. Gonzalez SR, Wolter KG, Yuen JC. Infectious complications associated with the use of Integra: a systematic review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(7):e2869. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002869

29. Suzuki S, Matsuda K, Maruguchi T, Nishimura Y, Ikada Y. Further applications of “bilayer artificial skin.” Br J Plast Surg. 1995;48(4):222–229. doi:10.1016/0007-1226(95)90006-3

30. Bargues L, Boyer S, Leclerc T, Duhamel P, Bey E. Incidence and microbiology of infectious complications with the use of artificial skin Integra® in burns [Article in French]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2009;54(6):533–539. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2008.10.013

31. Gray RJ, Pockaj BA, Vega ML, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of malignant melanoma of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(9):696-705. doi:10.1177/107110070602700908

32. Bateni SB, Nguyen P, Eskander A, et al. Changes in health care costs, survival, and time toxicity in the era of immunotherapy and targeted systemic therapy for melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(11):1195-1204. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.3179

33. Tsao H, Rogers GS, Sober AJ. An estimate of the annual direct cost of treating cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(5 Pt 1):669-680. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70195-1

34. Chevalier J, Bonastre J, Avril MF. The economic burden of melanoma in France: assessing healthcare use in a hospital setting. Melanoma Res. 2008;18(1):40-46. doi:10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282f36203

35. Guy GP Jr, Ekwueme DU, Tangka FK,

Richardson LC. Melanoma treatment costs: a systematic review of the literature, 1990–2011. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):537-545. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.031