Reporting of Social Demographics in Diabetic Foot Ulcer Randomized Controlled Trials: A Scoping Review

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Diabetic foot ulcerations (DFUs) remain a major public health issue, disproportionately affecting diverse populations. The extent to which race, ethnicity, and social demographics are reported in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on graft treatments for DFU remains unclear. Objective. To assess the reporting frequency of these patient characteristics and social determinants of health in order to provide insight into providing more representative, evidence-based care. Methods. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, a scoping review of PubMed was conducted for RCTs on graft treatment for DFU published in the years 2014 to 2024. Studies were screened for the reporting and analysis of demographics, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health. Results. Among 63 studies, 100% reported age, 98% reported sex, and 67% reported weight or body mass index. Race and ethnicity were reported in 46% and 27% of studies, respectively. Insurance and socioeconomic class were noted in 2% and 3% of studies, respectively, with no income data reported. Bivariate or multivariate analyses of these variables in relation to outcomes were performed for age (10%), sex (13%), race (11%), and ethnicity (8%). Conclusion. Reporting of race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health in RCTs on grafting for DFU is limited. Given the effect of these factors on outcomes, future studies should prioritize them to improve research representation and patient care.

Affecting just over one-third of persons with diabetes during their lifetime, diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) remain a frequently encountered pathology with life-altering consequences.1 With approximately half of such ulcerations resulting in infection, and 20% of those modereate to severe infections leading to some type of amputation, appreciating both determinants that are inherent to the infectious process and determinants that are extrinsic to it remains imperative to treatment.2 Whether bioengineered skin substitutes or other means of skin replacement, adjuvants to traditional wound care used in an effort to heal such ulcerations have been extensively studied.3,4 However, with previous investigations showing that racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to develop diabetes and subsequent ulcerations and amputations compared with White individuals, understanding the role of similar social determinants of health provides an important framework when treating these DFUs.5

Across surgical specialties, race has been shown to play a role in surgical outcomes. For example, Black patients had an increased rate of postoperative complications and mortality following hip and knee arthroplasty when compared with White patients.6 There has been infrequent reporting and analysis of race and ethnicity across orthopedic surgery and its subspecialties.7 Although underrepresentation and disparate outcomes related to race and ethnicity have been documented in other surgical specialties, similar analyses remain limited in orthopedics, which continues to raise concern among clinicians, researchers, and health-equity stakeholders. Enrolling and reporting findings representative of the population that treatment modalities are intended to treat remains challenging.8 While there is no paucity of data concerning randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on DFU treatment, little is known about the population from which these investigations pool their samples, if this is reported at all.

To the knowledge of the authors of the present study, no prior studies have specifically analyzed the reporting of race, ethnicity, and other demographics within RCTs investigating graft-based treatments for DFUs. The primary aim of the present study is to describe the proportion of these RCTs that report race, ethnicity, and other basic patient demographics. Secondary aims of this study are to record the frequency with which social determinants of health are reported. Results of this investigation will shed light on patient characteristics that are being reported in the highest-level studies and will drive an evidence-based approach to care. These findings will support clinicians and researchers in considering the representative population studied in these RCTs as compared with the patients they encounter in various practice types and locations.

Methods

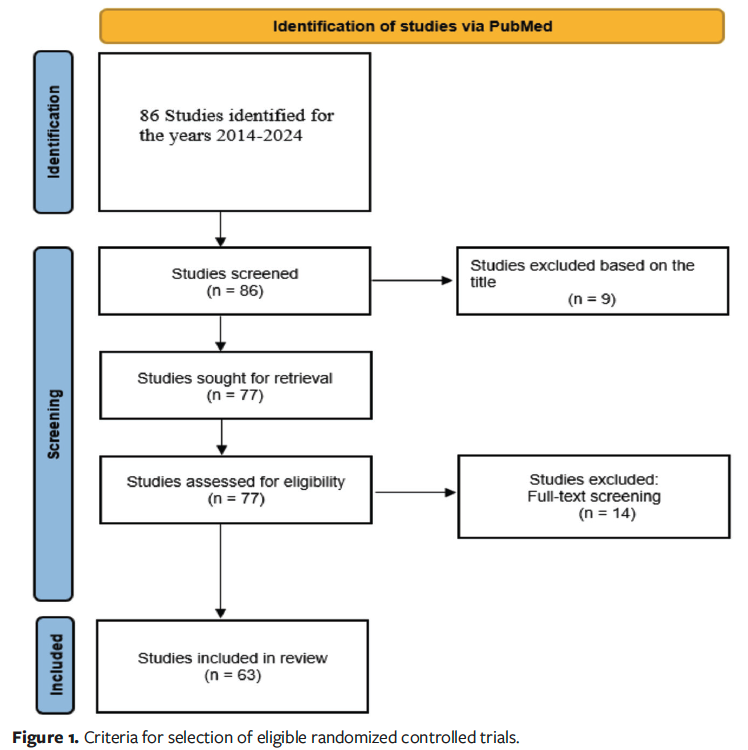

A scoping review using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines was performed, as illustrated in Figure 1, using methodology that closely followed that of a previous investigation.7 The following terms were searched on PubMed, with filters specific for RCTs for the years 2014 to 2024: diabetic foot ulcer and advanced wound care dressing, biological wound cover, regenerative skin matrix, bioengineered skin graft, dermal substitute, wound matrix, cellular tissue product, synthetic skin substitute, allograft, xenograft, collagen wound matrix, epidermal replacement, bioactive wound care product, and acellular dermal matrix.

Following identification and screening for studies that met final inclusion criteria, articles were assessed for the presence of age, sex, height, weight, race, ethnicity, insurance coverage, socioeconomic class, and income. Sex was defined as the biological classification of male or female as reported in the articles. Race was defined as a socially constructed categorization based on physical characteristics, and ethnicity was defined as cultural identification, language, or heritage. In studies that used these terms interchangeably, they were recorded according to the terminology provided in the original study. Although not explicitly labeled as such, insurance coverage, socioeconomic class, and income were treated as proxies for social determinants of health, which were defined as societal systems and their components that control the distribution of resources and hazards, shaping health outcomes and demographic patterns.9

Reporting of these variables included simply publishing that such variables were recorded. Reporting of analysis of these variables was also assessed in relation to the outcome of interest. Any statistical testing beyond basic between-group demographic comparisons, including analyses of variables outside of demographics or bivariate or multivariate analyses within this group, was assessed. Results were reported in the form of counts and frequencies. Data was recorded and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Washington).

Results

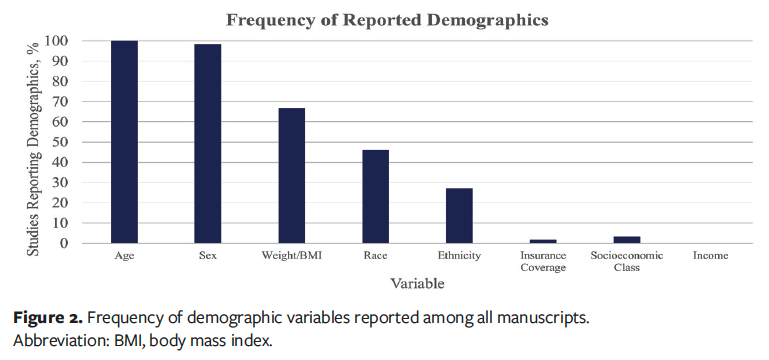

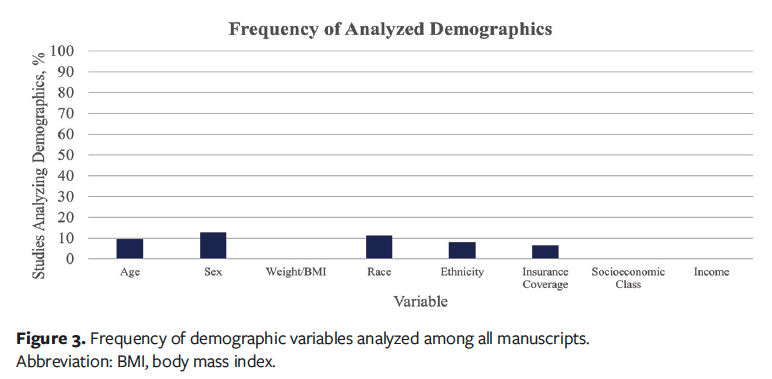

After applying the selection criteria, a total of 63 studies were analyzed, with various demographic and socioeconomic characteristics mentioned across the studies, as reported in Figure 2.10-73 Age was reported in all studies (100%), and sex was noted in 98%. Weight or body mass index (BMI) was reported in 67% of the studies, indicating moderate coverage of body composition–related metrics. Race was mentioned in 46% of the studies, and ethnicity was noted in 27%. In contrast, only 2% of articles included data concerning insurance coverage, making it one of the least mentioned variables. The proportion of studies that included bivariate or multivariable analyses of these respective demographic measurements were 10% for age, 13% for sex, 11% for race, and 8% for ethnicity as shown in Figure 3.

Discussion

Defined as the societal systems and resources that influence health by distributing, allocating, or withholding benefits and risks, leading to changes in health outcomes across different demographic groups, social determinants of health play an important role in patient care.9 Socioeconomic disadvantages have been found to contribute to an increased burden of mortality in patients with diabetes who develop foot ulceration.73 Similarly, determinants such as residential address have been associated with infection of DFU.74 While biologic and other adjuvant therapies aim to accelerate the healing process of DFUs, acknowledging the influence of social determinants of health is important when interpreting the efficacy of these adjuvant therapies. This scoping review analyzes both the reporting and the analysis of such variables as they pertain to RCTs on DFU treatment.

The results of the present investigation show that whereas the majority of RCTs reported the typical demographic data such as age, sex, and weight or BMI, less than half reported race or ethnicity. Moreover, there was little to no mention of insurance coverage, socioeconomic status, or income. This infrequency in reporting similar variables has been reported in orthopedic literature.7,75 Along with the minimal reporting of these social determinants of health, there is even less analysis of these determinants as they relate to the outcomes of interest. While baseline comparison between control and experimental groups remains standard so as to ensure cohorts remain comparable, this does not entirely reflect the influence of social determinants on outcomes. Notably, in wound care as a whole, it has been found that the patient’s environment, urban or rural, is responsible for up to 50% variation in wound healing.76 Although there is debate regarding whether collection of such data is required for institutional review board approval, it remains important to include these assessment points with consideration for the population being surveyed. For example, previous studies have indicated differences in willingness to participate among racial and ethnic groups, often depending on the nature of the study.77 Hesitancy may stem from historical abuses, for example the Tuskegee Syphilis Study or prior unethical medical experimentation, as well as from language barriers, for example lack of translated materials or limited access to bilingual research staff; future protocols should account for these challenges.77-79

To improve the representativeness and external validity of future wound care RCTs, a broader range of social determinants of health should be systematically collected. Although not examined in the present investigation due to limited reporting among existing RCTs, variables such as education level, employment status, and primary language are essential, because they influence health literacy, adherence to off-loading and dressing regimens, and the ability to engage in follow-up care.80-83 Additional determinants, including food security, transportation access, caregiver coordination, and housing stability, also play meaningful roles in wound healing and treatment adherence.84-86 Importantly, these factors are relevant not only to DFU but to wound care research more broadly because they affect access to care, capacity for self-management, and overall healing trajectories across diverse wound types. Incorporating these variables into study design and reporting will strengthen the applicability of RCT findings to real-world clinical populations.

Limitations

This scoping review has limitations. First, because only RCTs published from 2014 to 2024 were reviewed, there may be relevant or newer studies that were not captured. Second, the sole reliance on PubMed for the literature search may have excluded pertinent studies in other databases. Finally, the study does not assess the reasons for the underreporting of key demographics, nor does it evaluate the effect of this underreporting on clinical outcomes, both of which are areas that warrant further investigation. Despite these limitations, the outcomes shared in this study provide insight into the current deficiencies among RCTs on DFU.

Conclusion

The reporting of race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health in RCTs on graft treatment for DFU remains insufficient. Given the established link between diabetic complications and these factors, inclusion of these factors in future research is critical. Incorporating these variables from the outset, including in project proposals and in submission for institutional review board approval, will enhance the relevance of findings and lead to more representative evidence-based care. Future studies should prioritize comprehensive demographic reporting to improve clinical outcomes for diverse populations.

Improving reporting practices requires understanding why these gaps persist. Underreporting may reflect inconsistent institutional requirements, the perception that social factors are secondary, or recruitment barriers such as mistrust and language differences. Furthermore, limited demographic transparency may reduce the external validity of DFU RCTs and risks perpetuating inequities in care. Without adequate representation, trial findings may not capture the populations most affected by diabetic complications. Standardized expectations for reporting demographic and social determinants of health are needed to strengthen scientific rigor and ensure that advances benefit diverse patient groups equitably.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Dominick J. Casciato, DPM1; Kevin Ruiz, MS-42; Nigel Morris, DPM1; and Joshua Calhoun, DPM1

Affiliations: 1Orlando VA Medical Center, Orlando, FL, USA; 2University of Central Florida College of Medicine, Orlando, FL, USA

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge Stephen L. Smith, PhD, senior medical writer at Medline Industries, LP, for providing medical writing support in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors would also like to acknowledge Grace Furman, BS, associate biostatistician at Medline Industries, LP, for providing data analysis.

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the the Orlando VA Healthcare System.

Disclosure: No financial disclosures or conflicts of interest are reported by the authors. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Correspondence: Dominick J. Casciato, DPM; Orlando VA Medical Center, 13800 Veterans Way, Orlando, FL 32827; dominickcasciatodpm@gmail.com.

Manuscript Accepted: November 13, 2025

References

1. Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(24):2367–2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1615439

2. Armstrong DG, Tan TW, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic foot ulcers: a review. JAMA. 2023;330(1):62-75. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.10578

3. Primous NR, Elvin PT, Carter KV, et al. Bioengineered skin for diabetic foot ulcers: a scoping review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(5):1221. doi:10.3390/jcm13051221

4. Santema TB, Poyck PPC, Ubbink DT. Skin grafting and tissue replacement for treating foot ulcers in people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2(2):CD011255. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011255.pub2

5. Clayton EO, Njoku-Austin C, Scott DM, Cain JD, Hogan MV. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of diabetic feet. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(11):550-556. doi:10.1007/s12178-023-09867-7

6. Adelani MA, Archer KR, Song Y, Holt GE. Immediate complications following hip and knee arthroplasty: does race matter? J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(5):732-5. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.09.015

7. Paul RW, Lee D, Brutico J, Tjoumakaris FP, Ciccotti MG, Freedman KB. Reporting and analyzing race and ethnicity in orthopaedic clinical trials: a systematic review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(5):e21.00027. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00027

8. Alnahhal KI, Wynn S, Gouthier Z, et al. Racial and ethnic representation in peripheral artery disease randomized clinical trials. Ann Vasc Surg. 2024;108:355-364. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2024.05.034

9. Hahn RA. What is a social determinant of health? Back to basics. J Public Health Res. 2021;10(4):2324. doi:10.4081/jphr.2021.2324

10. Lantis Ii JC, Lullove EJ, Liden B, et al. Final efficacy and cost analysis of a fish skin graft vs standard of care in the management of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial. Wounds. 2023;35(4):71-79. doi:10.25270/wnds/22094

11. Wu Y, Shen G, Hao C. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is superior to conventional moist dressings in wound bed preparation for diabetic foot ulcers: A randomized controlled trial. Saudi Med J. 2023;44(10):1020-1029. doi:10.15537/smj.2023.44.20230386

12. Wang C, Yu X, Sui Y, Zhu J, Zhang B, Su Y. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Data Features to Evaluate the Efficacy of Compound Skin Graft for Diabetic Foot. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2022;2022:5707231. Published 2022 Jun 13. doi:10.1155/2022/5707231

13. Nolan GS, Smith OJ, Heavey S, Jell G, Mosahebi A. Histological analysis of fat grafting with platelet-rich plasma for diabetic foot ulcers-A randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2022;19(2):389-398. doi:10.1111/iwj.13640

14. Shetty R, Giridhar BS, Potphode A. Role of ultrathin skin graft in early healing of diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized controlled trial in comparison with conventional methods. Wounds. 2022;33(2):57-67. doi:10.25270/wnds/2022.5767

15. Shaked G, Czeiger D, Abu Arar A, Katz T, Harman-Boehm I, Sebbag G. Intermittent cycles of remote ischemic preconditioning augment diabetic foot ulcer healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(2):191-196. doi:10.1111/wrr.12269

16. Niederauer MQ, Michalek JE, Liu Q, Papas KK, Lavery LA, Armstrong DG. Continuous diffusion of oxygen improves diabetic foot ulcer healing when compared with a placebo control: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre study. J Wound Care. 2018;27(Sup9):S30-S45. doi:10.12968/jowc.2018.27.Sup9.S30

17. Lavery L, Fulmer J, Shebetka KA, et al. Open-label Extension Phase of a Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcer Multicenter, Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial Using Cryopreserved Placental Membrane. Wounds. 2018;30(9):283-289.

18. Gould LJ, Orgill DP, Armstrong DG, et al. Improved healing of chronic diabetic foot wounds in a prospective randomised controlled multi-centre clinical trial with a microvascular tissue allograft. Int Wound J. 2022;19(4):811-825. doi:10.1111/iwj.13679

19. Moon KC, Suh HS, Kim KB, et al. Potential of Allogeneic Adipose-Derived Stem Cell-Hydrogel Complex for Treating Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes. 2019;68(4):837-846. doi:10.2337/db18-0699

20. Lullove EJ, Liden B, McEneaney P, et al. Evaluating the effect of omega-3-rich fish skin in the treatment of chronic, nonresponsive diabetic foot ulcers: penultimate analysis of a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trial. Wounds. 2022;34(4):E34-E36. doi:10.25270/wnds/2022.e34e36

21. Snyder RJ, Shimozaki K, Tallis A, et al. A Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter, Controlled Evaluation of the Use of Dehydrated Amniotic Membrane Allograft Compared to Standard of Care for the Closure of Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Wounds. 2016;28(3):70-77.

22. Malekpour Alamdari N, Shafiee A, Mirmohseni A, Besharat S. Evaluation of the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma on healing of clean diabetic foot ulcers: A randomized clinical trial in Tehran, Iran. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15(2):621-626. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2021.03.005

23. Armstrong DG, Orgill DP, Galiano R, et al. A multicentre, randomised controlled clinical trial evaluating the effects of a novel autologous, heterogeneous skin construct in the treatment of Wagner one diabetic foot ulcers: Interim analysis. Int Wound J. 2022;19(1):64-75. doi:10.1111/iwj.13598

24. Armstrong DG, Galiano RD, Orgill DP, et al. Multi-centre prospective randomised controlled clinical trial to evaluate a bioactive split thickness skin allograft vs standard of care in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2022;19(4):932-944. doi:10.1111/iwj.13759

25. You HJ, Han SK, Rhie JW. Randomised controlled clinical trial for autologous fibroblast-hyaluronic acid complex in treating diabetic foot ulcers. J Wound Care. 2014;23(11):521-530. doi:10.12968/jowc.2014.23.11.521

26. Zelen CM, Orgill DP, Serena TE, et al. An aseptically processed, acellular, reticular, allogenic human dermis improves healing in diabetic foot ulcers: A prospective, randomised, controlled, multicentre follow-up trial. Int Wound J. 2018;15(5):731-739. doi:10.1111/iwj.12920

27. Smith OJ, Leigh R, Kanapathy M, et al. Fat grafting and platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: A feasibility-randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2020;17(6):1578-1594. doi:10.1111/iwj.13433

28. Lullove EJ, Liden B, Winters C, McEneaney P, Raphael A, Lantis Ii JC. A Multicenter, Blinded, Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Evaluating the Effect of Omega-3-Rich Fish Skin in the Treatment of Chronic, Nonresponsive Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Wounds. 2021;33(7):169-177. doi:10.25270/wnds/2021.169177

29. Carter MJ. Dehydrated human amnion and chorion allograft versus standard of care alone in treatment of Wagner 1 diabetic foot ulcers: a trial-based health economics study. J Med Econ. 2020;23(11):1273-1283. doi:10.1080/13696998.2020.1803888

30. DiDomenico LA, Orgill DP, Galiano RD, et al. Use of an aseptically processed, dehydrated human amnion and chorion membrane improves likelihood and rate of healing in chronic diabetic foot ulcers: A prospective, randomised, multi-centre clinical trial in 80 patients. Int Wound J. 2018;15(6):950-957. doi:10.1111/iwj.12954

31. Ananian CE, Dhillon YS, Van Gils CC, et al. A multicenter, randomized, single-blind trial comparing the efficacy of viable cryopreserved placental membrane to human fibroblast-derived dermal substitute for the treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2018;26(3):274-283. doi:10.1111/wrr.12645

32. Thompson P, Hanson DS, Langemo D, Anderson J. Comparing Human Amniotic Allograft and Standard Wound Care When Using Total Contact Casting in the Treatment of Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32(6):272-277. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000557831.78645.85

33. Zelen CM, Orgill DP, Serena T, et al. A prospective, randomised, controlled, multicentre clinical trial examining healing rates, safety and cost to closure of an acellular reticular allogenic human dermis versus standard of care in the treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2017;14(2):307-315. doi:10.1111/iwj.12600

34. Cazzell SM, Caporusso J, Vayser D, Davis RD, Alvarez OM, Sabolinski ML. Dehydrated Amnion Chorion Membrane versus standard of care for diabetic foot ulcers: a randomised controlled trial. J Wound Care. 2024;33(Sup7):S4-S14. doi:10.12968/jowc.2024.0139

35. Tettelbach W, Cazzell S, Sigal F, et al. A multicentre prospective randomised controlled comparative parallel study of dehydrated human umbilical cord (EpiCord) allograft for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2019;16(1):122-130. doi:10.1111/iwj.13001

36. Cazzell S, Vayser D, Pham H, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a human acellular dermal matrix demonstrated superior healing rates for chronic diabetic foot ulcers over conventional care and an active acellular dermal matrix comparator. Wound Repair Regen. 2017;25(3):483-497. doi:10.1111/wrr.12551

37. Zelen CM, Orgill DP, Serena TE, et al. Human Reticular Acellular Dermal Matrix in the Healing of Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcerations that Failed Standard Conservative Treatment: A Retrospective Crossover Study. Wounds. 2017;29(2):39-45.

38. Tettelbach W, Cazzell S, Reyzelman AM, Sigal F, Caporusso JM, Agnew PS. A confirmatory study on the efficacy of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane dHACM allograft in the management of diabetic foot ulcers: A prospective, multicentre, randomised, controlled study of 110 patients from 14 wound clinics. Int Wound J. 2019;16(1):19-29. doi:10.1111/iwj.12976

39. Hu Z, Zhu J, Cao X, et al. Composite Skin Grafting with Human Acellular Dermal Matrix Scaffold for Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(6):1171-1179. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.02.023

40. Lavery LA, Fulmer J, Shebetka KA, et al. The efficacy and safety of Grafix(®) for the treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: results of a multi-centre, controlled, randomised, blinded, clinical trial. Int Wound J. 2014;11(5):554-560. doi:10.1111/iwj.12329

41. Manning L, Ferreira IB, Gittings P, et al. Wound healing with "spray-on" autologous skin grafting (ReCell) compared with standard care in patients with large diabetes-related foot wounds: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2022;19(3):470-481. doi:10.1111/iwj.13646

42. Sanders L, Landsman AS, Landsman A, et al. A prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial comparing a bioengineered skin substitute to a human skin allograft. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60(9):26-38.

43. Zelen CM, Gould L, Serena TE, Carter MJ, Keller J, Li WW. A prospective, randomised, controlled, multi-centre comparative effectiveness study of healing using dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane allograft, bioengineered skin substitute or standard of care for treatment of chronic lower extremity diabetic ulcers. Int Wound J. 2015;12(6):724-732. doi:10.1111/iwj.12395

44. Zelen CM, Serena TE, Gould L, et al. Treatment of chronic diabetic lower extremity ulcers with advanced therapies: a prospective, randomised, controlled, multi-centre comparative study examining clinical efficacy and cost. Int Wound J. 2016;13(2):272-282. doi:10.1111/iwj.12566

45. Armstrong DG, Orgill DP, Galiano R, et al. A multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the effects of a novel autologous heterogeneous skin construct in the treatment of Wagner one diabetic foot ulcers: Final analysis. Int Wound J. 2023;20(10):4083-4096. doi:10.1111/iwj.14301

46. Frykberg RG, Marston WA, Cardinal M. The incidence of lower-extremity amputation and bone resection in diabetic foot ulcer patients treated with a human fibroblast-derived dermal substitute. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2015;28(1):17-20. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000456630.12766.e9

47. Driver VR, Lavery LA, Reyzelman AM, et al. A clinical trial of Integra Template for diabetic foot ulcer treatment. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23(6):891-900. doi:10.1111/wrr.12357

48. Frykberg RG, Cazzell SM, Arroyo-Rivera J, et al. Evaluation of tissue engineering products for the management of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers: an interim analysis. J Wound Care. 2016;25(Sup7):S18-S25. doi:10.12968/jowc.2016.25.Sup7.S18

49. Lantis JC, Snyder R, Reyzelman AM, et al. Fetal bovine acellular dermal matrix for the closure of diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective randomised controlled trial. J Wound Care. 2021;30(Sup7):S18-S27. doi:10.12968/jowc.2021.30.Sup7.S18

50. Gilligan AM, Waycaster CR, Landsman AL. Wound closure in patients with DFU: a cost-effectiveness analysis of two cellular/tissue-derived products. J Wound Care. 2015;24(3):149-156. doi:10.12968/jowc.2015.24.3.149

51. Guest JF, Weidlich D, Singh H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of using adjunctive porcine small intestine submucosa tri-layer matrix compared with standard care in managing diabetic foot ulcers in the US. J Wound Care. 2017;26(Sup1):S12-S24. doi:10.12968/jowc.2017.26.Sup1.S12

52. Liao C, Zhu M, Ding H, Li Y, Sun Q, Li X. Comparing the traditional and emerging therapies for enhancing wound healing in diabetic patients: A pivotal examination [retracted in: Int Wound J. 2025 Apr;22(4):e70473. doi: 10.1111/iwj.70473.]. Int Wound J. 2024;21(3):e14488. doi:10.1111/iwj.14488

53. Campitiello F, Mancone M, Corte AD, Guerniero R, Canonico S. Expanded negative pressure wound therapy in healing diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective randomised study. J Wound Care. 2021;30(2):121-129. doi:10.12968/jowc.2021.30.2.121

54. Djavid GE, Tabaie SM, Tajali SB, et al. Application of a collagen matrix dressing on a neuropathic diabetic foot ulcer: a randomised control trial. J Wound Care. 2020;29(Sup3):S13-S18. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.Sup3.S13

55. Armstrong DG, Orgill DP, Galiano RD, et al. Use of a purified reconstituted bilayer matrix in the management of chronic diabetic foot ulcers improves patient outcomes vs standard of care: Results of a prospective randomised controlled multi-centre clinical trial. Int Wound J. 2022;19(5):1197-1209. doi:10.1111/iwj.13715

56. Armstrong DG, Orgill DP, Galiano RD, et al. A multi-centre, single-blinded randomised controlled clinical trial evaluating the effect of resorbable glass fibre matrix in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2022;19(4):791-801. doi:10.1111/iwj.13675

57. Mujica V, Orrego R, Fuentealba R, Leiva E, Zúñiga-Hernández J. Propolis as an Adjuvant in the Healing of Human Diabetic Foot Wounds Receiving Care in the Diagnostic and Treatment Centre from the Regional Hospital of Talca. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:2507578. Published 2019 Sep 12. doi:10.1155/2019/2507578

58. Çetinkalp Ş, Gökçe EH, Şimşir I, et al. Comparative Evaluation of Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Collagen Laminin-Based Dermal Matrix Combined With Resveratrol Microparticles (Dermalix) and Standard Wound Care for Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2021;20(3):217-226. doi:10.1177/1534734620907773

59. Kesavan R, Sheela Sasikumar C, Narayanamurthy VB, Rajagopalan A, Kim J. Management of Diabetic Foot Ulcer with MA-ECM (Minimally Manipulated Autologous Extracellular Matrix) Using 3D Bioprinting Technology - An Innovative Approach. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2024;23(1):161-168. doi:10.1177/15347346211045625

60. Chandler LA, Alvarez OM, Blume PA, et al. Wound Conforming Matrix Containing Purified Homogenate of Dermal Collagen Promotes Healing of Diabetic Neuropathic Foot Ulcers: Comparative Analysis Versus Standard of Care. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2020;9(2):61-67. doi:10.1089/wound.2019.1024

61. Hahn HM, Lee DH, Lee IJ. Ready-to-Use Micronized Human Acellular Dermal Matrix to Accelerate Wound Healing in Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Prospective Randomized Pilot Study. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2021;34(5):1-6. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000741512.57300.6d

62. Liden BA, Ramirez-GarciaLuna JL. Efficacy of a polylactic acid matrix for the closure of Wagner grade 1 and 2 diabetic foot ulcers: a single-center, prospective randomized trial. Wounds. 2023;35(8):E257-E260. doi:10.25270/wnds/23094

63. Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Dahle SE, Lev-Tov H, et al. Cellular versus acellular matrix devices in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: Interim results of a comparative efficacy randomized controlled trial. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;13(8):1430-1437. doi:10.1002/term.2884

64. Campitiello F, Mancone M, Della Corte A, Guerniero R, Canonico S. To evaluate the efficacy of an acellular Flowable matrix in comparison with a wet dressing for the treatment of patients with diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized clinical trial. Updates Surg. 2017;69(4):523-529. doi:10.1007/s13304-017-0461-9

65. Lee M, Han SH, Choi WJ, Chung KH, Lee JW. Hyaluronic acid dressing (Healoderm) in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer: A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-center study. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(3):581-588. doi:10.1111/wrr.12428

66. Gasca-Lozano LE, Lucano-Landeros S, Ruiz-Mercado H, et al. Pirfenidone Accelerates Wound Healing in Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Randomized, Double-Blind Controlled Trial. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:3159798. doi:10.1155/2017/3159798

67. Hiller J, Stratmann B, Timm J, Costea TC, Tschoepe D. Enhanced growth factor expression in chronic diabetic wounds treated by cold atmospheric plasma. Diabet Med. 2022;39(6):e14787. doi:10.1111/dme.14787

68. Armstrong DG, Orgill DP, Galiano RD, et al. A purified reconstituted bilayer matrix shows improved outcomes in treatment of non-healing diabetic foot ulcers when compared to the standard of care: Final results and analysis of a prospective, randomized, controlled, multi-centre clinical trial. Int Wound J. 2024;21(4):e14882. doi:10.1111/iwj.14882

69. Yao M, Hasturk H, Kantarci A, et al. A pilot study evaluating non-contact low-frequency ultrasound and underlying molecular mechanism on diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2014;11(6):586-593. doi:10.1111/iwj.12005

70. Viswanathan V, Juttada U, Babu M. Efficacy of Recombinant Human Epidermal Growth Factor (Regen-D 150) in Healing Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Hospital-Based Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2020;19(2):158-164. doi:10.1177/1534734619892791

71. Lee YJ, Han HJ, Shim HS. Treatment of hard-to-heal wounds in ischaemic lower extremities with a novel fish skin-derived matrix. J Wound Care. 2024;33(5):348-356. doi:10.12968/jowc.2024.33.5.348

72. Irani PS, Ranjbar H, Mehdipour-Rabori R, Torkaman M, Amirsalari S, Alazmani-Noodeh F. The Effect of Aloe vera on the Healing of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Randomized, Double-blind Clinical Trial. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2024;21(3):56-63. doi:10.2174/1570163820666230904150945

73. Anderson SG, Shoo H, Saluja S, et al. Social deprivation modifies the association between incident foot ulceration and mortality in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study of a primary-care cohort. Diabetologia. 2018;61(4):959-967. doi:10.1007/s00125-017-4522-x

74. Schmidt BM, Huang Y, Banerjee M, Hayek SS, Pop-Busui R. Residential address amplifies health disparities and risk of infection in individuals with diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(3):508-515. doi:10.2337/dc23-1787

75. Solomon E, Gupta M, Su R, et al. Trends and rates of reporting of race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health in spine surgery randomized clinical trials: a systematic review. Clin Spine Surg. 2025;38(3):123-131. doi:10.1097/bsd.0000000000001675

76. Sen CK, Roy S. Sociogenomic approach to wound care: a new patient-centered paradigm. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2019;8(11):523-526. doi:10.1089/wound.2019.1101

77. Milani SA, Swain M, Otufowora A, Cottler LB, Striley CW. Willingness to participate in health research among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: does race/ethnicity matter? J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(3):773-782. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00839-y

78. George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e16-31. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706

79. Heffernan ME, Barrera L, Guzman ZR, et al. Barriers and facilitators to recruitment of underrepresented research participants: perspectives of clinical research coordinators. J Clin Transl Sci. 2023;7(1):e193. doi:10.1017/cts.2023.611

80. Rodrigues S, Isabel Patrício A, Cristina C, Fernandes F, Marcelino Santos G, Antunes I, Pintalhão I, Ribeiro M, Lopes R, Moreira S, Oliveira SA, Costa SP, Simões S, Nunes TC, Santiago LM, Rosendo I. Health Literacy and Adherence to Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Portugal. Health Lit Res Pract. 2024 Oct;8(4):e194-e203. doi: 10.3928/24748307-20240625-01. Epub 2024 Oct 8. PMID: 39378075; PMCID: PMC11610626.

81. Alrashed FA, Iqbal M, Al-Regaiey KA, Ansari AA, Alderaa AA, Alhammad SA, Alsubiheen AM, Ahmad T. Evaluating diabetic foot care knowledge and practices at education level. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024 Aug 23;103(34):e39449. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000039449. PMID: 39183414; PMCID: PMC11346884.

82. Abrar EA, Yusuf S, Sjattar EL, Rachmawaty R. Development and evaluation educational videos of diabetic foot care in traditional languages to enhance knowledge of patients diagnosed with diabetes and risk for diabetic foot ulcers. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(2):104-110. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2019.06.005

83. Palmer KNB, Crocker RM, Marrero DG, Tan TW. A vicious cycle: employment challenges associated with diabetes foot ulcers in an economically marginalized Southwest US sample. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc. 2023 Apr 14;4:1027578. doi: 10.3389/fcdhc.2023.1027578. PMID: 37124466; PMCID: PMC10140327.

84. Cleary CM, Aitcheson E, Courtright D, et al. Utilization of Subsidized Transportation Services Improves Wound Healing and Care Coordination in a Limb Preservation Program. Ann Vasc Surg. Published online October 15, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2025.10.009

85. Imel BE, McClintock HF. Food Security and Medication Adherence in Young and Middle-Aged Adults with Diabetes. Behav Med. 2023;49(1):96-103. doi:10.1080/08964289.2021.1987855

86. Zamani N, Chung J, Evans-Hudnall G, et al. Engaging patients and caregivers to establish priorities for the management of diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(4):1388-1395.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2020.08.127