Triple-Positive PALB-2 Breast Cancer in a 27-Year-Old Male-to-Female Patient

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Introduction. There is a paucity of literature describing breast cancer prevention and screening guidelines in transgender patients. As more patients undergo gender-affirming care, breast cancer screening guidelines must be solidified for transgender patients. While there are no published incidence rates of breast cancer in the transgender population, case reports continue to underscore the prevalence of breast cancer in transgender females.

Methods. A 27-year-old transgender woman with a family history of breast cancer and personal gender-affirming hormone therapy for 9 years was diagnosed with stage 3 invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient presented with a palpable breast lump and had never undergone breast imaging.

Conclusions. Breast cancer risk in transgender patients with long-term hormone therapy use is not well understood. Individuals, both male and female, with a family history of breast cancer; increased cumulative lifetime estrogen and progesterone use; or mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PTEN, or PALB2 genes have an increased risk for breast cancer. Hormonal treatment is often used alongside gender-affirming surgeries for development of female secondary sex characteristics in male-to-female patients. Although hormone therapy can have gender-affirming benefits, the increased lifetime exposure to estrogen and progesterone can increase the risk of breast cancer. Mammography guidelines for transgender patients vary by age, familial and genetic risk, as well as duration of hormone therapy. Three current organizations have published mammographic screening guidelines for transgender patients: the University of California San Francisco, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, and the American College of Radiology. Future research should focus on substantiating these guidelines with greater data to produce evidence-based recommendations to guide the care of transgender patients.

Introduction

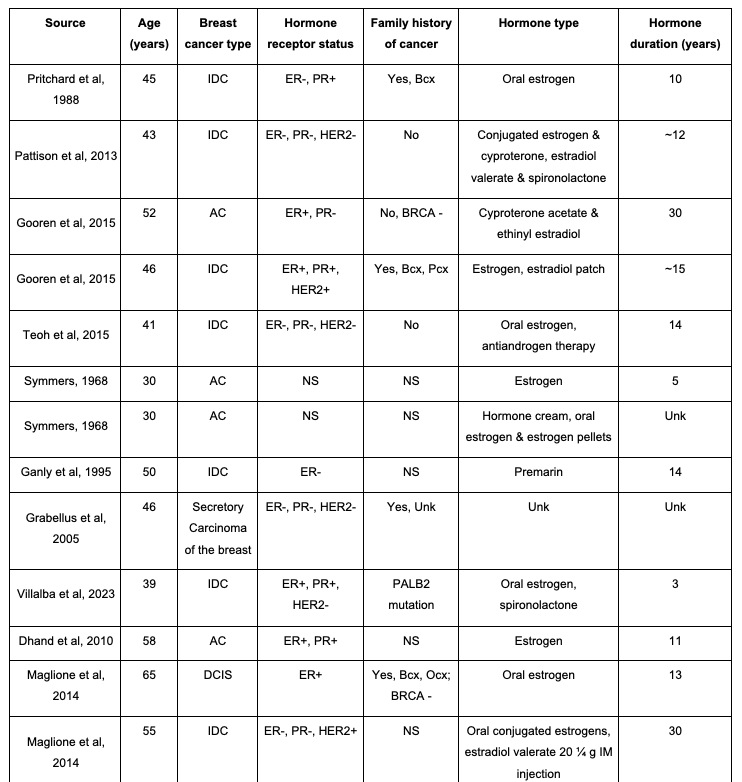

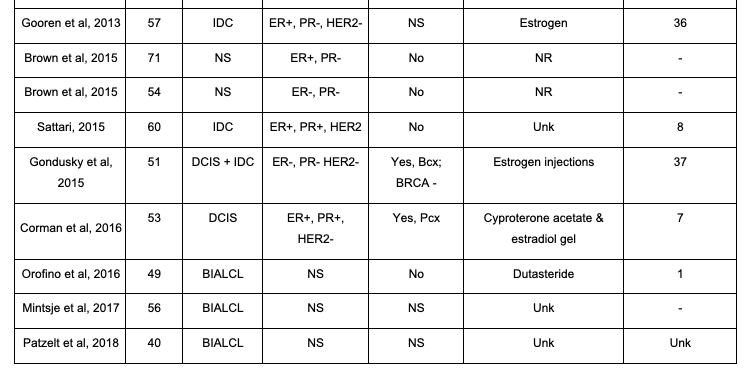

Breast cancer, typically associated with cisgender women, remains a seldom-seen yet impactful occurrence within the transgender community, with only 22 reported cases of non–implant-based breast cancer worldwide since 1968 (Table 1).1

Gender-affirming care demands a multidisciplinary approach tailored to each individual's unique journey of transition. Whether it involves gender-affirming surgeries like chest masculinization or feminization, hormone replacement therapy, or other nonsurgical options, these interventions aim to align outward appearances with inner identities. Among the common therapies, exogenous hormone therapy—utilizing estrogen, progesterone, or testosterone—stands prominent, though not without associated risks. Prolonged estrogen use, especially in conjunction with genetic mutations, heightens the risk of breast cancer. De Blok et al reported 15 cases of breast cancer out of 2260 transfeminine patients who had been undergoing hormone therapy for a median of 18 years. Another study out of the Netherlands found that transfeminine patients have a 46-fold increased risk of breast cancer compared to cisgender men.2

In this context, we present the case of a 27-year-old male-to-female transgender individual with a significant family history of breast cancer and a 9-year history of exogenous hormone therapy who presented with a palpable mass in the right breast.

The lack of literature addressing breast cancer in transgender women highlights the need to expand our understanding and knowledge base. We aim to contribute this unique case to the existing body of information, offering insights for health care providers navigating the complexities of caring for transgender individuals susceptible to breast cancer or other complications stemming from exogenous hormone therapy. Additionally, we discuss the challenges encountered while treating a transfeminine patient, emphasizing the use of tissue expanders followed by reconstruction to maintain aesthetic appearances. Finally, we explore the histopathological findings and elaborate on the treatment regimen tailored to this patient's case.

Case Presentation

We present a case of a 27 year old MtF transgender patient who presented with a mass in the right breast. She had not yet undergone any gender-affirming surgeries. The patient had been under estrogen and bioidentical hormone treatment for the past 9 years, starting at age 18. Family history was significant for breast cancer in both the patient's mother and maternal grandmother, prostate cancer in both the patient's father and paternal grandfather, pancreatic cancer in her maternal grandfather, and lung cancer in her maternal uncle. Other than an extensive family history of cancer and prolonged estrogen exposure, the patient had no other known risk factors for breast cancer.

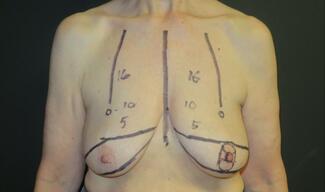

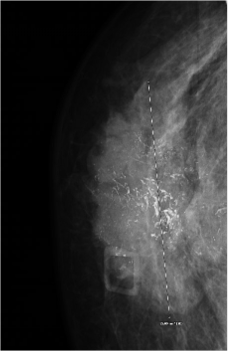

Following her presentation in clinic, a mammogram and magnetic resonance imaging were performed and showed a 4.7 × 1.8 × 5.0-cm subareolar mass extending to the nipple areolar complex and skin that involved all 4 quadrants of the breast but did not demonstrate any extension of the mass to the pectoralis muscle (Figure 1). The patient and her physicians agreed on pursuing both surgical treatment and chemotherapy. The patient initially underwent a right skin-sparing mastectomy with right targeted sentinel lymph node biopsy and immediate right breast reconstruction with a tissue expander. The histopathology report demonstrated a biopsy-proven metastatic right lymph node, and the patient was diagnosed with stage 3 invasive ductal carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated triple-positive receptors: estrogen receptor positive (ER+), progesterone receptor positive (PR+), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive (HER2+). Genetic testing revealed a variant of uncertain significance in PALB2 (c.866T>C; p.Leu289Ser), the partner and localizer of BRCA2.

Figure 1. Irregular right breast findings. The image shows a highly suspicious irregular spiculated heterogenous hypoechoic mass with multiple microcalcifications that extends to the skin surface. This mass is approximately 4.7 × 1.8 × 5.0 cm.

After surgery, the patient underwent 6 cycles of combination neoadjuvant docetaxel (Taxotere, Sanofi), carboplatin (Paraplatin), trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech), pertuzumab (Perjeta, Genentech), known as TCHP. The patient is currently 3 months out from surgery and is closely following her health care team’s instructions. She has no evidence of disease recurrence. She plans to continue with her reconstruction and gender-affirming surgeries.

Discussion

We report a case of a PALB2 mutation in a MtF transgender patient with breast cancer. The patient was first diagnosed at 27 years of age with stage 3 invasive ductal carcinoma after nine years of hormonal treatment. The patient had an extensive family history of breast cancer, and testing revealed triple-positive receptors—ER-positive, PR-positive, and HER2-positive—as well as a PALB2 variant of uncertain significance, c.866T>C (p.Leu289Ser).

Breast cancer continues to be the second most common cause of cancer-related death in women but remains outside of the top 10 causes of cancer-related death in men in the United States.3 In the United States, breast cancer is approximately 100 times less common among white cis-males than white cis-females, and approximately 70 times less common among black cis-males than black cis-females.4 Both males and females are at an increased risk of breast cancer in the setting of family history of breast cancer, increased lifetime estrogen and progesterone exposure, and mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PTEN, or PALB2 genes. Family history is the biggest risk factor in men, with 20% of men with breast cancer having a close relative with breast cancer.4 In cisgender females, higher estrogen and progesterone levels can be caused by various factors such as earlier age of menses, late menopause, early age of first pregnancy, not breastfeeding, nulliparity, and hormonal birth control.5 For men, higher estrogen and progesterone levels can be caused by increased alcohol intake, liver disease, obesity, radiation exposure, testicular conditions, estrogen therapy, or genetic conditions such as Klinefelter syndrome.4

Patients who decide to undergo transition from male to female often use hormonal treatment alongside gender-affirming surgeries to assist with the development of female secondary sex characteristics and minimization of male secondary sex characteristics.6 This is often true for patients who undergo female-to-male transition as well. Generally, for patients who transition from male to female, patients undergo hormone treatment therapy that consists of 2 or 3 parts estrogen, an androgen blocker, and sometimes a progestogen. The combination of these hormones can help the patient develop “feminine” characteristics such as breasts, redistribute fat in the face or body, and reduce muscle mass and body hair, and will also affect the patient’s libido, sperm count, testicle size, and erectile function.6 These hormones can also have an effect on the patient’s social and emotional daily functioning.

The type of estrogen used in feminizing hormone therapy is chemically identical to the type of estrogen found in a female ovary, 17-beta estradiol. It is delivered in a similar manner to those who are menopausal or agonadal, via a transdermal patch, oral tablet, or injection of a conjugated ester (estradiol valerate or estradiol cypionate).6 The androgen blockers used for feminizing hormone therapy are commonly spironolactone and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.6 Although some patients may add progestogens to their feminizing hormone therapy regimen, progestogens have not been proven to have a significant nor harmful role in transgender care. However, some patients have had improved mood, libido, and breast development with progesterone use.6,7 Although feminizing hormone therapy can have positive effects and benefits for patients undergoing transition from male to female, the increased lifetime exposure to estrogen and progesterone levels can cause an increased risk of breast cancer.

While there is no clear correlation between feminizing hormone therapy and breast cancer development in patients transitioning from male to female, the options for hormone therapy after diagnosis of breast cancer must be further investigated. There is no current treatment algorithm that explains hormone therapy options in cases where patients develop breast cancer, undergo unilateral or bilateral mastectomies, and desire further gender-affirming surgeries. Panichella et al discussed several cases of various breast cancer diagnoses with hormone therapy alone and in patients who had been diagnosed after chest feminizing surgeries.8 The study found inconsistencies between each case, with some patients choosing to continue their gender-affirming hormone therapies after cancer diagnosis against medical advice, and some patients electing to stop hormone therapies altogether.8 Further research must be conducted to understand the complexities of continuing hormone therapy in male-to-female patients who have been diagnosed with breast cancer and have undergone unilateral or bilateral mastectomy.

Treatment options for male-to-female patients who are diagnosed with breast cancer vary on a case-by-case basis, depending on the type of breast cancer diagnosed, the mutation associated with the diagnosis, and the patient’s goals of care. Panichella et al discussed several cases of BRCA mutations in male-to-female patients.8 The study found that most patients with a BRCA mutation discontinued feminizing hormone therapy, which appears to be the standard of care for this patient population; however, several BRCA mutation patients chose to continue feminizing hormone therapy.8 Alongside hormone therapy are surgical options for the treatment of breast cancer.

For male-to-female patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic mutations and no prior gender-affirming care or risk-reducing mastectomy, Bedrick et al recommend following the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for cisgender males with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.10 Patients should be offered a risk-reducing mastectomy to remove native breast tissue before chest feminizing surgery, similar to the guidelines for their cisgender female counterparts. Patients who have had risk-reducing mastectomies are recommended to have yearly clinical examinations. Male-to-female patients who are carriers and have had hormonal therapy, surgical therapy, or both forms of gender-affirming care,11 and are without a risk-reducing mastectomy should receive individualized care dependent on family history, age of transition, and degree of gynecomastia.11 Further research is needed to determine management of male-to-female patients who have other mutations such as CHEK2, PTEN, and PALB2 and how to proceed with feminizing hormone therapy or other surgical therapies after breast cancer diagnosis and treatment.

The current mammography guidelines for cisgender females are mammography screening every year for women with average risk starting at 40 years old. Average risk is defined as having no known family history of breast, ovarian, or pancreatic cancer; known genetic mutation; or chest radiation between the ages of 10 and 30 years old.12 For cisgender females who have increased risk due to family history, that individual should be screened with annual mammography 7 to 10 years prior to when the youngest family member was diagnosed with cancer.12 For cisgender females who have increased risk due to chest radiation, screening should begin 8 years after radiation was completed; however, annual mammography should not begin before age 30 years.12

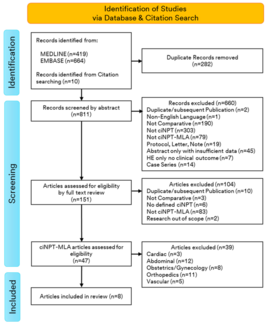

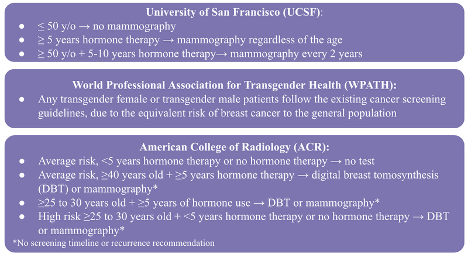

The current mammography guidelines for transgender females vary between organizations and depend on the individual's age, risk, and length of hormone therapy use (Figure 2). The guidelines from the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) suggest that due to a likely lower incidence of breast cancer in transgender females, it is recommended that screening mammography begin after a minimum of 5 years of feminizing hormone therapy, regardless of the age.13 UCSF does not recommend transgender women undergo screening mammography before the age of 50 years.13 Ultimately, UCSF recommends that transgender women undergo screening mammography every 2 years starting at 50 years of age if they have completed 5 to 10 years of feminizing hormone therapy.13 The World Professional Association for Transgender Health recommends that any transgender female or transgender male patients follow the existing cancer screening guidelines, due to the equivalent risk of breast cancer to the general population.14 The following recommendations are from the American College of Radiology (ACR). Transgender females with average risk who are at least 40 years old with 5 or more years of hormonal use are recommended to use digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) or mammography with no screening timeline or recurrence surveillance recommendation.15,16,17 For transgender females with average risk who have less than 5 years of hormone use, no screening test is recommended. For transgender females who are at least 25 to 30 years old with at least 5 years of hormone use, DBT or mammography is appropriate with no screening timeline or recurrence surveillance recommendation.15,16,17 For higher-risk transgender females who are at least 25 to 30 years of age with less than 5 years of hormone use, DBT or mammography is recommended with no screening timeline or recurrence surveillance recommendation.,15, 16,17

Figure 2. Current mammography guidelines. These are the current organizations with published mammography screening guidelines for transgender patients.

With these guidelines in mind, our 27-year-old patient who presented with 9 years of gender-affirming hormone therapy and extensive breast cancer family history would have met the above criteria for breast cancer screening. Theoretically, our patient should have undergone one of the ACR screening recommendations, mammography or DBT, up to 2 years prior to presentation, as the guidelines were released in 2021 and she would have met both the age and hormone therapy duration criteria at that time. The timely screening of this patient may have allowed for an earlier diagnosis, and may have possibly led to less invasive treatment. This case reinforces the importance of remaining up to date with screening recommendations to prevent delay in care as well as escalation in therapeutic interventions due to the disease progression.

There is a paucity of data in the literature demonstrating breast cancer diagnoses in transgender female patients, especially those who are younger. Currently, there are only 22 published case reports on transgender female patients who developed breast cancer, with the average age of 49.5 years old (ranging from 30-71 years old). Of these 22 cases, 18% are under the age of 40 and 82% are over the age of 40 (Table 1). Although most of these patients are over the age of 40, the current patient in a younger age group adds to the necessity for re-evaluation of mammography screening for transgender female patients. There is one other study published with a known PALB2 mutation in a transgender patient; however this individual was 12 years older than the current patient, had a shorter duration of hormone therapy, and did not have a triple-positive tumor biology.18 Although there are many factors that may contribute to a transgender female’s risk of breast cancer, current literature demonstrates a need for a closer investigation of the relationship between mutation type, hormone therapy duration and dosing, as well as the age of the patient.

Table 1. Breast Cancer Cases in Male-To-Female

This table highlights the 22 currently published male-to-female transgender case reports. Details highlighted are age at diagnosis, breast cancer type, hormone receptor status, family history of cancer, hormone treatment type, and hormone treatment duration. AC, adenocarcinoma; Bcx, breast cancer; BIALCL, breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma; BRCA: breast cancer gene; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; IM: Intra-Muscular; NR, not reported; NS, not specified; Ocx, ovarian cancer; Pcx, prostate cancer; PR, progesterone receptor; Unk: unknown.

Conclusions

As the number of individuals taking gender-affirming exogenous hormones continues to rise, an increased awareness and understanding of breast cancer risk in transgender females is necessary. Further, more research on the guidelines for breast cancer screening in transgender females must be performed to address the diverse needs of this population. This case represents a 27-year-old transgender female with an extensive family history of cancer, including breast cancer in her mother and maternal grandmother, and 9 years of exogenous hormone therapy who was diagnosed with stage 3 invasive ductal carcinoma. This patient fell within the guidelines of mammography or DBT screening, as she was within the age range of 25 to 30 years with more than 5 years of hormone therapy. However, she was not diagnosed until the age 27 years when she felt a palpable lump. This case illustrates the importance of individualized breast cancer risk assessment and adherence to screening guidelines in transgender females. Clinicians treating transgender females must remain vigilant of evolving guidelines and recommendations as more information in this emerging field is elucidated.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Kelly C. Ho, BS1; Kristin N. Huffman, BS1; Madeline J. O’Connor, BA1; Payton Sparks, BS3; Caden Bozigar1; Helene Sterbling, MD2; Nora Hansen, MD2

Affiliations: 1Department of Surgery, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois; 2Department of Surgery, Division of Breast Surgery, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois; 3Marian University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana

Correspondence: Nora Hansen, MD; nora.hansen@nm.org

Disclosures: The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

References

- Cole NA, Copeland-Halperin LR, Shank N, Shankaran V. BRCA2-associated breast cancer in transgender women: reconstructive challenges and literature review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022 Apr 22;10(4):e4059. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000004059

- de Blok CJM, Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, et al. Breast cancer risk in transgender people receiving hormone treatment: nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. BMJ 2019;365:l1652. doi:10.1136/bmj.l1652

- Henkle T. Cancer Facts & Figures 2023. American Cancer Society. Published 2023. Accessed November 2023. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2023-cancer-facts-figures.html

- Henkle T. Key Statistics for Breast Cancer in Men. American Cancer Society. Published April 2018. Accessed November 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer-in-men/about/key-statistics.html

- Henkle T. Breast Cancer Risk Factors and Prevention Methods. American Cancer Society. Published December 2021. Accessed November 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/risk-and-prevention.html

- Deutsch MB. Overview of Feminizing Hormone Therapy. Gender Affirming Health Program. Published June 17, 2016. Accessed November 2023. https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/feminizing-hormone-therapy.

- Wierckx K, Gooren L, T'Sjoen G. Clinical review: breast development in trans women receiving cross-sex hormones. J Sex Med. 2014;11(5):1240-1247. doi:10.1111/jsm.12487

- Panichella JC, Araya S, Nannapaneni S, et al. Cancer screening and management in the transgender population: review of literature and special considerations for gender affirmation surgery. World J Clin Oncol. 2023;14(7):265-284. doi:10.5306/wjco.v14.i7.265

- Bedrick BS, Fruhauf TF, Martin SJ, Ferriss JS. Creating breast and gynecologic cancer guidelines for transgender patients with BRCA mutations. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138(6):911-917. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004597

- Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. NCCN. Published June 2022. Accessed November 2023. https://www.nccn.org/patientresources/patient-resources/guidelines-for-patients/guidelines-for-patients-details?patientGuidelineId=66

- Deutsch MB. Screening for Breast Cancer in Transgender Women. Gender Affirming Health Program. Published June 17, 2016. Accessed November 2023. https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/breast-cancer-women

- Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022 Sep 6;23(Suppl 1):S1-S259. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

- Expert Panel on Breast Imaging, Brown A, Lourenco AP, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® transgender breast cancer screening. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(11S):S502-S515. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2021.09.005

- Lockhart R, Kamaya A. Patient-friendly summary of the ACR appropriateness criteria: transgender breast cancer screening. J Am Coll Radiol. 2022;19(4):e19. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2021.10.015

- Santora T. The Confusing World of Breast Cancer Screening for Transgender People. Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines for Transgender People. Published October 19, 2023. Accessed November 2023. https://www.breastcancer.org/news/screening-transgender-non-binary.

- Villalba MD, Letter HP, Robinson KA, Maimone S. Breast cancer in a transgender woman undergoing gender-affirming exogenous hormone therapy. Radiol Case Rep. 2023 May 16;18(7):2511-2513. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2023.04.032