A Suitable Indication for Crescent Mastopexy: Achieving Optimal Nipple Position in Nipple-Sparing Mastectomies

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Questions

- What criteria determine a patient's candidacy for nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM)?

- What are the primary surgical options for breast reconstruction following NSM after oncologic treatment?

- What are the key considerations for performing crescent mastopexy, and what are the factors affecting its outcomes?

- What are the advantages of using crescent mastopexy in conjunction with NSM, and how can this combination enhance breast reconstruction outcomes?

Case Description

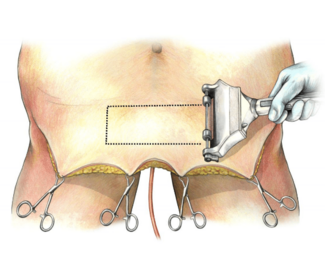

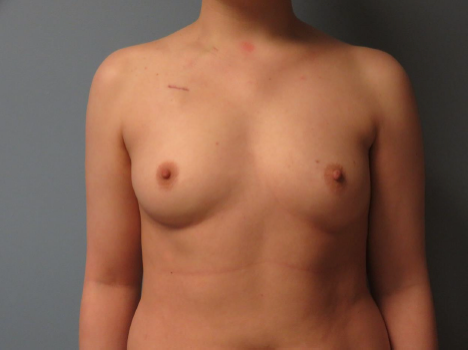

A 26-year-old woman with a history of fibromyalgia underwent 6 cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisting of Taxotere, carboplatin, Herceptin, and PERJETA for estrogen/progesterone receptor-positive, HER2-positive invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast. Preoperatively, it was noted that her left nipple-areolar complex (NAC) sat lower than the right, in addition to her inframammary fold sitting lower on her left side (Figure 1). She subsequently underwent bilateral nipple-sparing mastectomies (NSM) via an inframammary incision and a left axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy. Her mastectomies weighed 365 g on the left and 360 g on the right. During the same procedure, the plastic and reconstructive surgery (PRS) team performed bilateral breast reconstruction with subpectoral placement of 300-mL tissue expanders (TEs) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Preoperative image prior to bilateral nipple-sparing mastectomies with subpectoral tissue expander placement. The left nipple-areola complex is observed to be positioned lower compared with the opposite side, along with an asymmetry in the inframammary fold, which is also situated lower on the left.

Figure 2. Postoperative image following bilateral nipple-sparing mastectomies and subpectoral tissue expander placement. Persistent asymmetry of the left nipple-areola complex is noted, with its position remaining lower compared with the right side.

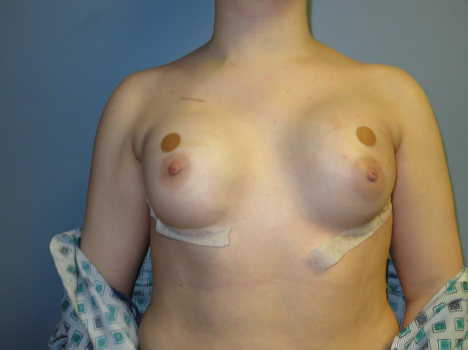

Three months later, after serial dilation of TEs to 490 mL on the left and 480 mL on the right, the PRS team conducted a bilateral expander-to-implant exchange with 550-mL high-profile subpectoral implants. Preoperative measurements demonstrated that the sternal notch-to-nipple distance was 18 cm on the right and 20 cm on the left, indicating grade 1 ptosis on the left. Therefore, in addition to the expander-to-implant exchange, the patient also underwent a left nipple-areolar revision using a crescent mastopexy to raise the NAC superiorly by 2 cm (Figure 3). A 2-year postoperative follow-up image was also included for longitudinal assessment (Figure 4). This case presentation highlights the candidacy, key considerations, and benefits of incorporating crescent mastopexy in conjunction with NSM reconstruction to optimize nipple positioning.

Figure 3. Postoperative image obtained 5 days after the exchange of tissue expanders for permanent implants. The position of the left nipple-areola complex was corrected using a crescent mastopexy, achieving a 2-cm elevation to improve symmetry.

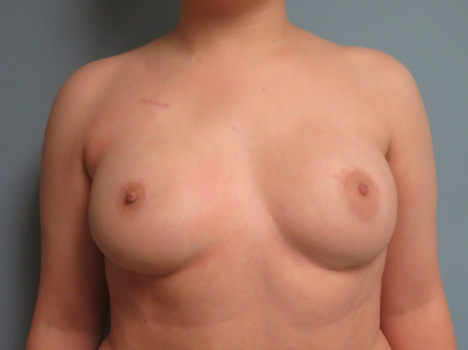

Figure 4. Two-year postoperative follow-up image demonstrating stable results, with no evidence of significant widening of the scar at the site of the crescent mastopexy incision on the left side.

Q1. What criteria determine a patient's candidacy for nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM)?

NSM is a minimally invasive approach for patients undergoing a mastectomy that improves cosmetic outcomes and quality of life. NSM was reportedly first performed in 1962. At that time, the procedure frequently encountered complications, raising concerns about its oncologic safety.1 At the time, the lack of scientifically backed selection criteria, crude reconstructive techniques, and excessive residual breast tissue caused NSM to fall out of favor quickly.2 NSM experienced a resurgence in 1999 when Hartmann et al published their work on the prophylactic use of NSM in women at high risk for breast cancer.3 This opened the door for more research into the technique, and numerous studies have demonstrated the oncologic safety of the procedure.4 As a result, NSM has become a viable option for breast cancer treatment and prophylactic breast tissue removal.5 There remains ongoing debate today regarding the criteria for patient selection, optimal surgical practices, and reconstruction options for NSM.

Historically, guidelines for NSM patient selection excluded patients with grade II or III ptosis, macromastia (C-cup breast size or larger), obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2), and pre- or post-mastectomy radiation.5,6 Patients with larger ptotic breasts were first excluded in 1968 when Sacchini et al excluded these patients from eligibility for NSM. The theory at the time was that, because NSM removes little skin, larger and more ptotic breasts were more likely to experience nipple or flap necrosis.2 Because of improved cosmetic outcomes, many surgeons have since developed techniques to refine their surgical approach to NSM, expanding the eligible patient population to include those with macromastia or grade II or III ptosis. Generally, if a patient is considered to have macromastia or grade II or III ptosis but still plans to undergo prophylactic NSM, they must first undergo either superior reduction mammaplasty or mastopexy to become eligible for NSM.7 This approach can be further differentiated based on the number of stages involved in the reconstruction. Currently, the literature suggests that NSM for large ptotic breasts may be performed in 1 to 3 stages of reconstruction.7-9

Ptosis and macromastia are no longer absolute contraindications for NSM, as eligibility depends on the surgeon and institution. Currently, it is widely accepted that patients with inflammatory breast cancer, imaging evidence of NAC involvement, new nipple inversion or dimpling, locally advanced breast cancer with skin involvement, or bloody nipple discharge are considered to have absolute contraindications for NSM.5

Q2: What are the primary surgical options for breast reconstruction following NSM after oncologic treatment?

Breast reconstruction following NSM can be performed either immediately or in a delayed fashion and can be divided into 2 broad groups: implant-based (alloplastic) and tissue-based (autologous). Implant-based reconstruction is more common, accounting for up to 73% of cases according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (2014).10,11

Implant-based reconstruction is typically performed in 2 stages. The first stage follows mastectomy with the insertion of TEs, placed either subpectorally or prepectorally.12 The TEs have a port that can be accessed easily through the skin with a needle for expansion. The TEs are then expanded weekly or biweekly with saline during clinic visits until the desired breast volume is reached.10 Once the desired breast volume is reached, the patient must return for a second procedure for an expander-to-implant exchange. An additional benefit of implant-based reconstruction is that it allows patients to provide consistent input on breast size. Issues such as capsular contracture, asymmetry, nipple reconstruction, fat grafting, and pocket adjustment can also be addressed during this second procedure to enhance patient satisfaction.12,13 Acellular dermal matrices are used in most 2-stage implant-based reconstructions to provide additional structural support and enhance aesthetic outcomes.14 Direct-to-implant reconstruction is another approach, typically performed with either partial submuscular or prepectoral coverage, and often involving a scaffold or acellular dermal matrix to reduce implant malposition.14 Direct-to-implant reconstructions are best suited for patients with smaller breast size who have undergone an NSM, have thick mastectomy flaps, have no history of smoking, and have minimal medical comorbidities.15,16

Autologous reconstruction techniques include fat grafting, local tissue rearrangement, pedicle flaps, and free flaps.17 Fat grafting involves harvesting fat from another part of the patient’s body, processing it (eg, centrifugation), and injecting it into the breast in small amounts to reconstruct its shape.17 Local tissue rearrangement is typically used for patients with larger, ptotic breasts following mastectomy, provided enough tissue remains to reshape the breast.17 An example of this is the Goldilocks method.17 Pedicle flap reconstruction involves using tissue from a nearby area that remains attached to its native blood supply, such as the latissimus dorsi or thoracodorsal artery perforator.17 This method is particularly useful when additional soft tissue is needed to cover implants or for complete autologous reconstruction (without implants).17 Lastly, free flap reconstruction involves tissue that is completely detached from its original site and transferred to the breast area using microsurgery. Donor sites for free flaps include the abdomen, buttocks, and thighs.17 Examples of free flaps include the transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap, while the deep inferior epigastric perforator flap is the most common.17

Q3: What are the key considerations for performing crescent mastopexy, and what are the factors affecting its outcomes?

The goal of breast reconstruction is to achieve bilateral symmetry, thereby improving the patient’s quality of life.18-20 This goal is often unachievable without a balancing procedure, such as a crescent mastopexy, to reposition the nipple to the desired location.

Crescent mastopexy involves a C-shaped de-epithelialization of the skin above the areola followed by skin closure to raise and reposition the NAC.21 Puckett et al were the first to describe crescent mastopexy as a procedure used to improve nipple position during breast augmentation in patients with mild ptosis.22 Crescent mastopexy provides a minimal lift when the NAC is positioned within 1.5 to 2 cm below the inframammary crease.22 Initially, crescent mastopexy was primarily used in cosmetic surgery.20 A well-documented limitation of crescent mastopexy is scar widening, which was reported in 46% of the patients studied by Puckett et al, along with oval areola deformities.22 The frequent complications associated with cosmetic crescent mastopexy quickly led to its abandonment. The reason for scar widening and nipple deformities can be attributed to the nipple remaining attached to the underlying breast glandular tissue. This connection exerts downward tension on the recently raised nipple, causing it to sag back toward its original position. This process leads to undesirable scarring and nipple deformities. This is why the only viable recent descriptions of the crescent mastopexy focus on relieving NAC tension to address these complications. For example, a full-thickness wedge of breast tissue from the skin to the pectoral fascia must be excised, instead of simply de-epithelializing the crescent.23 In summary, the modern implementation of the crescent mastopexy technique must emphasize approaches to reduce tension on the skin closure, prevent scar spreading, lift the inferior pole of the breast, and improve overall breast shape, while minimizing complications.23

Q4: What are the advantages of using crescent mastopexy in conjunction with NSM, and how can this combination enhance breast reconstruction outcomes?

Crescent mastopexy, traditionally used to correct mild ptosis, is introduced here as a method to address NAC asymmetry or implant-induced asymmetries following NSM. Nipple malposition is a significant and common risk following NSM with implant-based reconstruction. Several patient factors are thought to contribute to NAC malposition, including preoperative ptosis, the use of implants instead of autologous tissue, and a periareolar incision with lateral extension.24,25 Vertical nipple malposition rates following NSM have been reported to be as high as 75%.26 This necessitates frequent correction of nipple malposition following NSM and implant-based reconstruction. Crescent mastopexy is a viable solution for correcting nipple malposition; this technique allows NAC repositioning in any direction.27 Additionally, it is less invasive and technically more straightforward compared with other NAC repositioning methods.27 Preserving the NAC blood supply following NSM, particularly the subdermal vascular plexus, is critical. This is especially true in cases where inframammary incisions during NSM may compromise vascular integrity, as in this case. It is essential to avoid transecting the skin directly above the NAC, especially within 180 degrees of its superior aspect, to preserve vascular integrity. Accordingly, crescent mastopexy, limited to de-epithelialization, preserves NAC perfusion by sparing the subdermal vascular plexus.

In conclusion, we describe the unique application of crescent mastopexy for NAC repositioning following NSM and during breast reconstruction in a patient with preoperative grade I ptosis on the left, which persisted after submuscular TE implantation. Historically, crescent mastopexy in cosmetic procedures was associated with complications, primarily undesirable scarring, leading to its rapid decline in popularity. The key distinction in this case is the preceding NSM, which eliminated the weight of the breast glandular tissue before performing the crescent mastopexy. This reduction in glandular mass significantly decreased tension behind the nipple, minimizing downward nipple displacement and the risk of scarring. At 2 years and 10 months postoperative, the patient showed no evidence of scar widening or nipple deformities; photographs taken at the 2-year follow-up clearly demonstrate no evidence of scar widening (Figure 4). Thus, with refined surgical techniques emphasizing precise incision placement and minimizing scar tension, crescent mastopexy can achieve minimal scarring and deliver excellent cosmetic outcomes in patients with grade I ptosis or NAC asymmetries following NSM.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Ryan A. Cantrell, BS1; Alexander L. Mostovych, MS1; Claire Fell, BS1; Shriya D. Dodwani, BS1; Colton H. Connor, BS1; Quinton L. Carr, BA1; Camille Gorena, BS1; Bradon J. Wilhelmi, MD2

Affiliations: 1University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky; 2Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky

Correspondence: Bradon J. Wilhelmi, MD, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville, 550 South Jackson Street, ACB 2nd Floor, Louisville, KY 40202, USA. Email: bradon.wilhelmi@louisville.edu

Ethics: The patient illustrated in this document has been provided informed consent on the use of their images and granted the use of their images for scientific publications.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

References

1. Freeman BS. Subcutaneous mastectomy for benign breast lesions with immediate or delayed prosthetic replacement. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1962;30:676-682. doi:10.1097/00006534-196212000-00008

2. Spear SL, Hannan CM, Willey SC, Cocilovo C. Nipple-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(6):1665-1673. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a64d94

3. Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):77-84. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901143400201

4. De La Cruz L, Moody AM, Tappy EE, Blankenship SA, Hecht EM. Overall survival, disease-free survival, local recurrence, and nipple-areolar recurrence in the setting of nipple-sparing mastectomy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3241-3249. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4739-1

5. Tousimis E, Haslinger M. Overview of indications for nipple sparing mastectomy. Gland Surg. 2018;7(3):288-300. doi:10.21037/gs.2017.11.11

6. Coopey SB, Tang R, Lei L, et al. Increasing eligibility for nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(10):3218-3222. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3152-x

7. Economides JM, Graziano F, Tousimis E, Willey S, Pittman TA. Expanded algorithm and updated experience with breast reconstruction using a staged nipple-sparing mastectomy following mastopexy or reduction mammaplasty in the large or ptotic breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(4):688e-697e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000005425

8. Pontell ME, Saad N, Brown A, Rose M, Ashinoff R, Saad A. Single stage nipple-sparing mastectomy and reduction mastopexy in the ptotic breast. Plast Surg Int. 2018;2018:9205805. doi:10.1155/2018/9205805

9. Spear SL, Rottman SJ, Seiboth LA, Hannan CM. Breast reconstruction using a staged nipple-sparing mastectomy following mastopexy or reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(3):572-581. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318241285c

10. Regan JP, Casaubon JT. Breast Reconstruction. [Updated 2023 Jul 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470317/

11. Jonczyk MM, Jean J, Graham R, Chatterjee A. Surgical trends in breast cancer: a rise in novel operative treatment options over a 12 year analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;173(2):267-274. doi:10.1007/s10549-018-5018-1

12. Somogyi RB, Ziolkowski N, Osman F, Ginty A, Brown M. Breast reconstruction: updated overview for primary care physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(6):424-432.

13. Casella D, Di Taranto G, Marcasciano M, et al. Subcutaneous expanders and synthetic mesh for breast reconstruction: long-term and patient-reported BREAST-Q outcomes of a single-center prospective study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2019;72(5):805-812. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2018.12.018

14. Lennox PA, Bovill ES, Macadam SA. Evidence-based medicine: alloplastic breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(1):94e-108e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000003472

15. Gdalevitch P, Ho A, Genoway K, et al. Direct-to-implant single-stage immediate breast reconstruction with acellular dermal matrix: predictors of failure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(6):738e-747e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000000171

16. Brown MH, Somogyi RB, Aggarwal S. Secondary breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(1):119e-135e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002280

17. Shay P, Jacobs J. Autologous reconstruction following nipple sparing mastectomy: a comprehensive review of the current literature. Gland Surg. 2018;7(3):316-324. doi:10.21037/gs.2018.05.03

18. Nava MB, Rocco N, Catanuto G, et al. Impact of contra-lateral breast reshaping on mammographic surveillance in women undergoing breast reconstruction following mastectomy for breast cancer. Breast. 2015;24(4):434-239. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2015.03.009

19. Spear SL, Spittler CJ. Breast reconstruction with implants and expanders. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(1):177-187; quiz 188. doi:10.1097/00006534-200101000-00029

20. Cogliandro A, Brunetti B, Barone M, Favia G, Persichetti P. Management of contralateral breast following mastectomy and breast reconstruction using a mirror adjustment with crescent mastopexy technique. Breast Cancer. 2018;25(1):94-99. doi:10.1007/s12282-017-0796-6

21. Holmes DR, Schooler W, Smith R. Oncoplastic approaches to breast conservation. Int J Breast Cancer. 2011;2011:303879. doi:10.4061/2011/303879

22. Puckett CL, Meyer VH, Reinisch JF. Crescent mastopexy and augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75(4):533-543. doi:10.1097/00006534-198504000-00015

23. Handel N. Secondary mastopexy in the augmented patient: a recipe for disaster. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7 Suppl):152S-163S; discussion 164S-165S, 166S-167S. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000246106.85435.74

24. Chu CK, Carlson GW. Techniques and outcomes of nipple sparing mastectomy in the surgical management of breast cancer. Curr Breast Cancer Rep. 2013;5(2):118-124. doi:10.1007/s12609-013-0107-y

25. Nahabedian MY, Tsangaris TN. Breast reconstruction following subcutaneous mastectomy for cancer: a critical appraisal of the nipple-areola complex. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(4):1083-1090. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000202103.78284.97

26. Wagner JL, Fearmonti R, Hunt KK, et al. Prospective evaluation of the nipple-areola complex sparing mastectomy for risk reduction and for early-stage breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(4):1137-1144. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-2099-z

27. Small K, Kelly KM, Swistel A, Dent BL, Taylor EM, Talmor M. Surgical treatment of nipple malposition in nipple-sparing mastectomy device-based reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(5):1053-1062. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000000094