Stroke Assessment: BEFAST About It

The world of EMS is full of acronyms. People keep coming up with new ones to remember the steps of diagnosis, operations, or a procedure. There are a few that have become so imbedded early during EMT training that they are contained in the National Education Standards and most textbooks. Obtaining a SAMPLE history on the patient and using OPQRST to elaborate on the chief complaint have become not only standard and fairly easy to remember, but can also lead to more thorough assessments.

During the early decades of EMS, ischemic stroke care was largely supportive as there was no approved treatment for stopping and potentially reversing the effects of a cerebral occlusion. At its inception, dispatch prioritization considered stroke as a nonemergency call.

A Treatment Emerges

Response to and treatment of stroke took a leap ahead with the approval of Alteplase (tPA) in 1996. While used for almost a decade by that point for acute myocardial infarction, the new authorization provided the first major advance to help prevent further neuronal loss. The newly available therapy also required the rapid recognition of stroke along with prompt transport to an appropriate facility.

Need for Rapid Assessment

The standard for in-hospital assessment has been the NIH Stroke Scale for many years. While accurate in detecting strokes and their likely location, it consists of multiple steps that would be cumbersome to use in the prehospital environment where rapid identification and prenotification are key prerequisites for timely care. To meet this need, the University of Cincinnati Medical Center developed the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS) in 1997 as a simple version of the NIH scale that could be easily learned yet effective for rapid identification.

The three components involved assessment for facial droop, arm drift, and speech abnormalities. It was designed as a broad assessment for stroke, focusing on areas that at the time were considered to be most likely eligible for treatment. As public awareness of the need for emergency care became necessary to ensure that these patients were able to arrive at appropriate hospitals in a timely manner, FAST became a simple and widely utilized version for the public, emphasizing not only recognition of the signs, but also the need for timely intervention.

The Rise of Thrombectomy

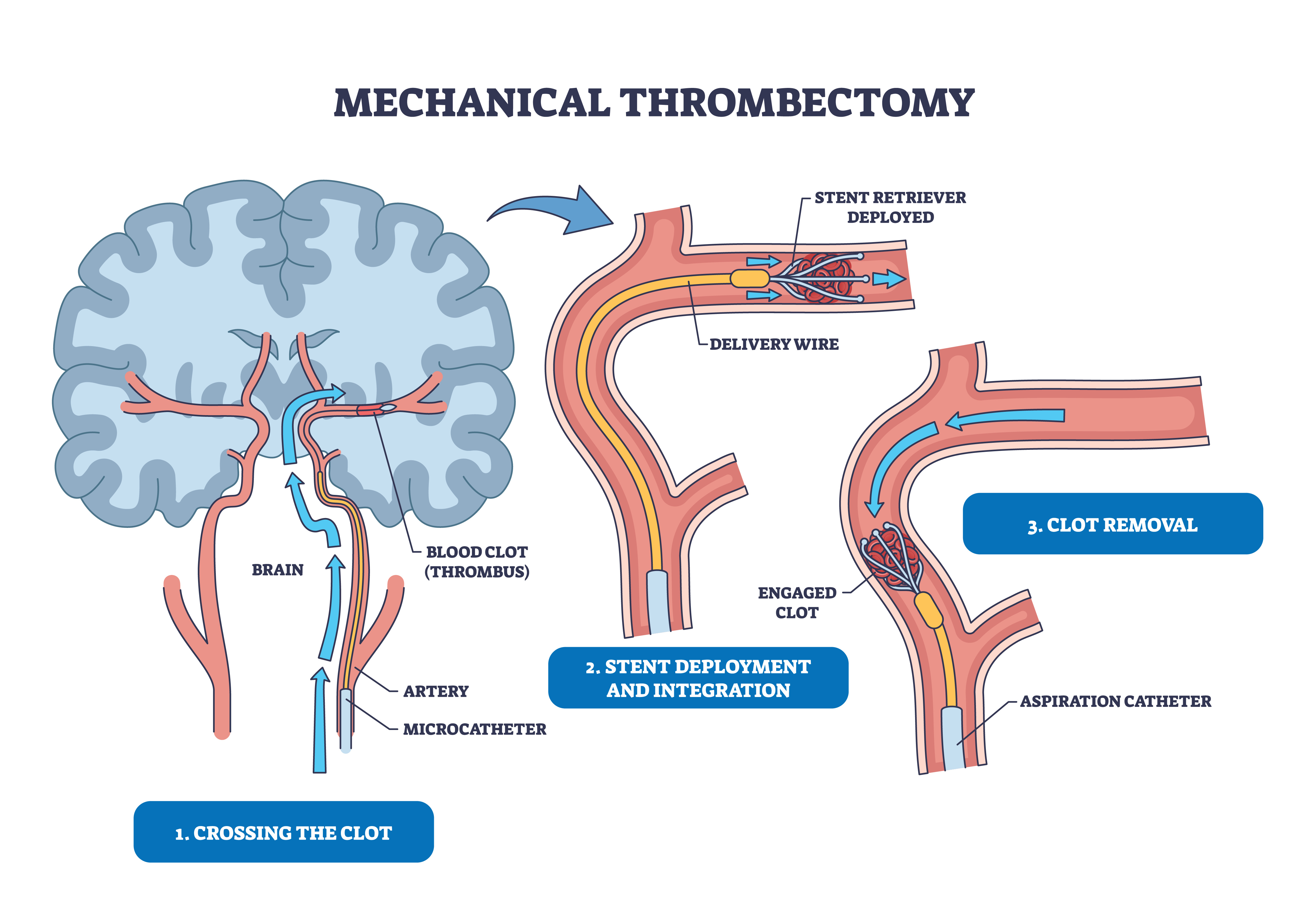

In 2015, clot retrieval devices demonstrated efficacy in removing clots from large vessel occlusions. While FAST answered the question of yes or no for a likely stroke, it was designed for rapid recognition rather than specifically for severity classification. Other scales are available to assist with this, including the Los Angeles Motor Score (LAMS), the Rapid Arterial oCclusion Evaluation (RACE) and the Field Assessment Stroke Triage for Emergency Destination (FAST-ED).

The approval of thrombectomy as a treatment for Large Vessel Occlusions (LVO) necessitated use of an additional prehospital stroke scale in order the help determine an appropriate receiving facility. Primary stroke centers are able to administer clot-busting drugs but are generally not capable of clot retrieving procedures on an emergency basis. These scales, as referenced above, help to determine the severity of deficits and assist in localization of the likely injury site.

A Simpler Clot-Buster

Treatment was further simplified with the approval of Tenecteplase (TNK) that enabled a single bolus injection without requiring a more cumbersome one-hour drip following an initial tPA injection. This relatively new drug is not only simpler to administer but is more fibrin-specific and less likely to cause bleeding. The need for recognition of posterior strokes also became evident.

To meet the need in a simple manner that was applicable to both lay-persons and healthcare providers, the acronym BEFAST was developed. In addition to the existing FAST assessment, balance/coordination, and the eye component of visual abnormalities were added, making a simple yet more comprehensive screening tool.

- Balance and Coordination: evidenced by ataxia, dizziness, uncoordinated finger to nose test

- Eye: visual disturbances, such as double vision, loss of visual field (not merely blurred vision)

- Face: have patient smile and show teeth, note asymmetry

- Arm: have patient hold arms out, eyes closed, palms up and note unilateral drift

- Speech: dysarthria, aphasia

- Time: while for the public it is time to call 9-1-1, for healthcare providers the Last Known Well is critical for care

Stroke Alert

Immediately upon obtaining a positive screening assessment, the receiving hospital should be alerted to allow adequate preparation and reduce door to treatment times. Once feasible and without delaying transport, a severity score should be obtained using an appropriate scale. As an example, the RACE score identifies three areas of motor deficits, namely facial droop, both arm and leg drift, and also three cortical signs, that are more likely to represent large vessel occlusions. These are gaze preference, aphasia and agnosia/neglect.

An important component is to learn the difference between dysarthria, which is difficulty speaking and is a motor sign, as opposed to aphasia, which is a more serious cortical sign that may be either receptive, expressive or both. The patient should be checked for the ability to comprehend and obey commands plus the ability to form and speak words. Note that slurred speech alone is dysarthria and not aphasia.

Stroke Triage

It has become a common expression that “time is brain.” This is because approximately 1.9 million neurons die every minute that stroke is not treated. There are also time limitations on treatment. Both tPA and TNK have only been demonstrated as being safe to administer up to four and one-half hours after the onset of symptoms, depending on the patient and findings. Thrombectomy was originally approved for up to six hours but further studies demonstrated its safety and efficacy up to 24 hours after onset.

Patients who experience a sudden, unexplained onset of a severe headache and those with high scores on a severity scale might be experiencing a hemorrhagic episode, which comprises approximately 13% of all strokes. These patients are best treated in a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) with the availability of neurosurgical care.

As stroke care has advanced, so has the need for rapid tools to identify and quantify severity that will aid in getting the patient to the proper destination for care. Whatever method your agency and medical director approve of for use, ensure that your assessment is performed promptly and thoroughly but never half-fast.

References

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke Screenings and Severity Tools for Large Vessel Occlusions. https://www.stroke.org/en/-/media/Stroke-Files/EMS-Resources/Stroke-Screening-and-Severity-Tools-for-LVO-PDF-ucm492585.pdf?sc_lang=en

Budincevic H. 2022. Stroke Scales as Assessment Tools in Emergency Settings: A Narrative Review.

Kothari R. 1997. Early stroke recognition: developing an out-of-hospital NIH Stroke Scale. Acad Emerg Med.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Acute Ischemic Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/about-ninds/what-we-do/impact/ninds-contributions-approved-therapies/tissue-plasminogen-activator-acute-ischemic-stroke-alteplase-activaser