Use of a Novel Debriding Agent Based on Collagenase and Hyaluronate Lyase to Enhance Angiogenesis, Stimulate Healing, and Reduce Pain in Chronic Cutaneous Wounds

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Chronic wounds pose a serious health challenge, reducing patient and caregiver quality of life and demanding substantial resources. Debridement is essential for healing, with collagenase being one of the most widely used agents. Objective. To determine the clinical efficacy and safety of a novel bioactive topical formulation combining collagenases G and H, and hyaluronate lyase, for treating chronic ulcers. Material and Methods. A prospective 2-arm longitudinal comparative interventional study was conducted. Twenty-five patients were allocated into 2 groups and treated for 21 days with conventional dressing. The intervention group (n = 17) additionally received the novel formulation, whereas the control group (n = 8) did not. Epithelialization, angiogenesis, and wound closure were evaluated, as well as patient satisfaction and product safety in terms of pain and adverse effects. Results. A significantly greater reduction in wound area was observed in the intervention group (baseline median area of 40.0 cm² vs final median area of 16.0 cm²; 60% reduction; P = .0004) compared with controls (baseline median area of 36.0 cm² vs final median area of 24.0 cm²; 33.3% reduction; P = .08). Histological analysis revealed significantly increased angiogenesis in the intervention group (P = .046). The product was rated as highly satisfactory by both physicians and patients in its use and results. Conclusion. The novel formulation demonstrated efficacy in promoting vascularization and reducing the wound area, indicating that it could be a valuable tool for treating chronic ulcers, with significant potential for promoting faster and more effective healing than conventional options.

Introduction

Chronic skin ulcers are disruptions in the normal structure and function of the skin, which is the body’s largest organ and its barrier to the external environment.1 This burden represents a silent yet widespread epidemic, significantly affecting patient quality of life and accounting for an estimated 1% to 5.5% of health care expenditures in developed countries.2 This growing challenge is compounded by an aging population and the rising global prevalence of conditions that impair healing, such as diabetes, inflammatory diseases, and obesity.3

Wound repair requires a coordinated sequence of overlapping events, including an inflammatory phase to clear debris and bacteria; a proliferative phase that promotes granulation tissue, epithelialization and angiogenesis; and a remodeling phase that completes closure.4,5 Healing disorders can lead to inadequate or excessive scarring4; the process may become arrested at the inflammatory stage, but it can be reversed through effective debridement.

It is broadly accepted that debridement is key to remove necrotic and devitalized tissue, reduce microbial burden, promote the transition toward the proliferative phase, and allow faster and more efficient healing. Debridement also creates a uniform bed for eventual grafting or application of biological dressing, and it prevents traumatic scarring.

The selection among different types of debridement (eg, surgical, enzymatic, autolytic, osmotic, mechanical, larval) depends on specific needs related to the particular wound characteristics.6,7 Several aspects of enzymatic debridement that have been highlighted as evidence of its superiority to other debridement methods include its selectiveness for necrotic tissue, which reduces the risk of damaging newly formed tissue and promotes a conducive healing environment; its minimal invasiveness, with less discomfort to the patient; and its potential for use in combination with other complementary strategies, such as advanced dressings, negative pressure wound therapy, and other debridement techniques. Enzymatic debridement can be tailored to specific aspects of the wound and patient, potentially improving outcomes in terms of scarring and healing time.8–11

Enzymatic agents degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) components and destroy necrotic tissue. This modulates the inflammatory response, promoting the transition toward tissue proliferation and repair. Among enzymatic options, widely used agents include collagenase, chymotrypsin plus trypsin, fibrinolysin, streptokinase-streptodornase, bromelain, and papain, each acting on different components of necrotic tissue and ECM, with collagenase being one of the most widely used.12

Collagenases specifically break down damaged collagen fibers present in the ECM, which is essential for promoting cellular migration and new tissue formation. Specifically, the action of collagenases G and H is critical during the early stages of wound healing. Hyaluronate lyase degrades hyaluronic acid, another major component of the ECM.13,14

The current study primarily aimed to assess the effect of the intervention on wound area reduction, with healing progression—including epithelialization and neovascularization—and pain reduction considered as secondary end points. To this end, a newly developed microemulsion-based product combining collagenases G and H with hyaluronate r-lyase, formulated for comfortable topical application, was tested.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This prospective randomized controlled longitudinal single-center comparative open-label study evaluated improvement in healing for wounds of various etiologies treated with Pbserum SHS30 (Proteos Biotech; hereafter “the product” or “the novel product”) in addition to conventional nonadherent dressings vs conventional nonadherent dressings only.

The total duration of the study was 2 years and 3 months. The experimental period for each patient lasted 21 days. This follow-up period was set to monitor the short-term safety of the product, as well as the healing progression of wounds that remain arrested in the inflammatory phase of the process.

Baseline measurements were taken at day 0 (D0), and the patients in the intervention group received the treatment that day. Follow-up visits were conducted at the center on day 7 (D7), day 14 (D14), and finally, day 21 (D21).

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was collected from patients prior to their enrollment in the study and before carrying out any study procedure that was not part of the usual clinical practice. The protocol and informed consent were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital “Dr. José Eleuterio González,” in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico.

The study was conducted in accordance with international regulations on clinical trials, including the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidance, and UNE-EN ISO 14155 Clinical Investigation of Medical Devices for Human Subjects – Good Clinical Practice. Additionally, all procedures adhered to the stipulations in the Regulations of the General Health Law Regarding Health Research (Mexico), specifically Title Two, Chapter I, Article 17, Section III, which covers research involving greater than minimal risk, with informed consent form attached; Third Title, Research on New Prophylactic, Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Rehabilitation Resources, Chapter I, Articles 61-64; and Title Three, Threat II, Pharmacological Research, Articles 65-71.15 This compliance ensured that all ethical and regulatory standards were met throughout the study.

Participant demographics

The target population for this investigation was thoughtfully selected, taking into consideration preexisting clinical data and specific cohort limitations designed to enable precise assessment of outcomes through the designated clinical end points.

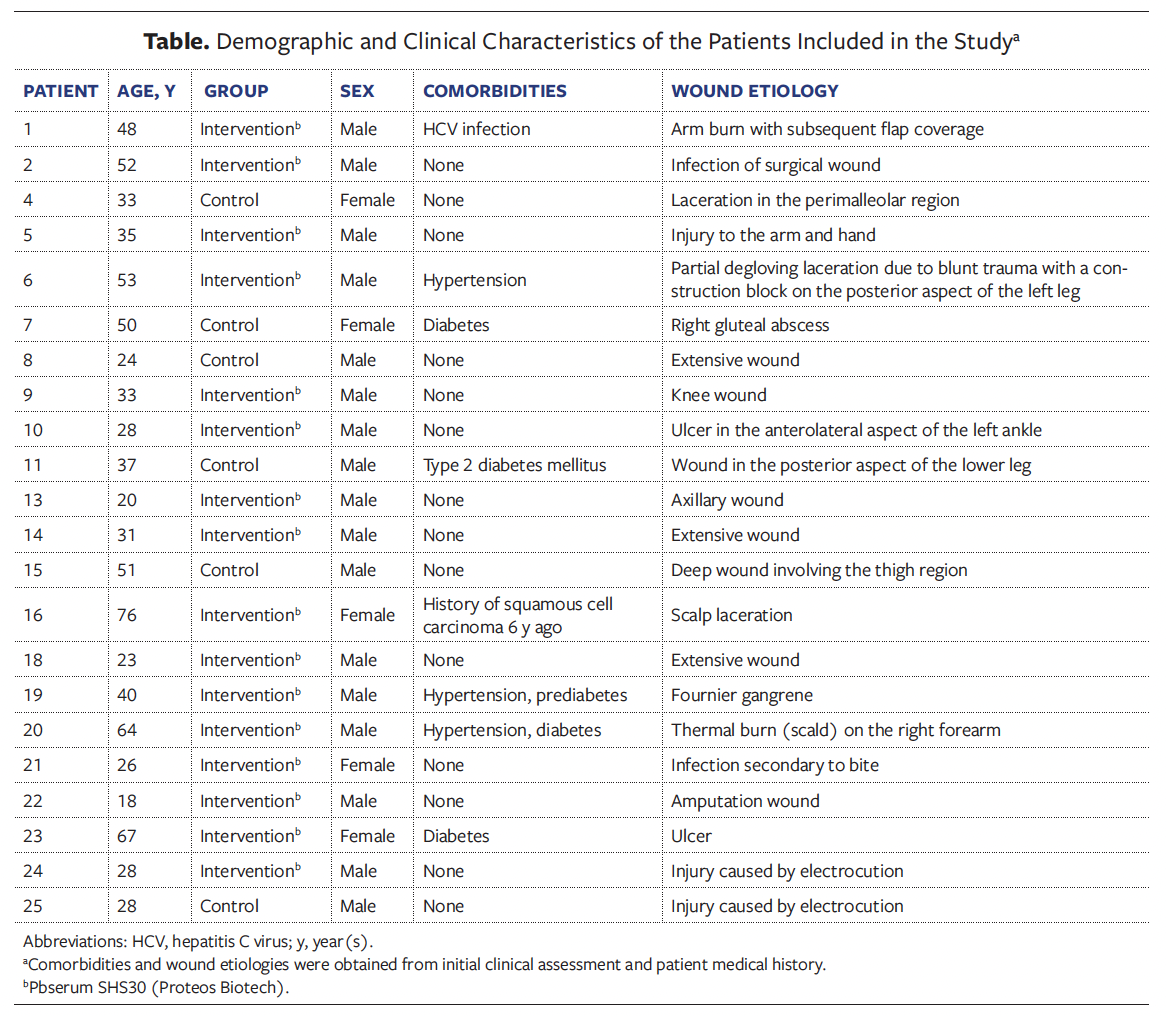

A total of 25 participants were distributed into the intervention group (n = 17) and the control group (n = 8) (Table). The participants were evenly distributed between groups by sex, with the intervention group having 82% male (n= 14) and 18% female (n= 3) participants and the control group 62.5% male (n= 5) and 37.5% female (n= 3) participants. The average age was 40.13 years in the intervention group and 37.17 years in the control group. Weight and height were comparable between groups, ensuring the baseline characteristics were balanced. The study was not blinded due to practical constraints in the clinical setting and product characteristics.

When the researcher determined that the wound had completely epithelialized as of a particular follow-up visit, the subject’s participation in the study concluded at that visit.

Three patients withdrew from the study, and 1 patient finished the study early because he met the epithelialization criterion before 21 days. Six patients in the control group and 16 patients in the intervention group completed the study.

Inclusion, exclusion, and withdrawal criteria

Inclusion criteria included males or females aged 18 to 65 years, with wounds of any origin with a size of at least 5 cm2. Adequate level of understanding of the clinical study and voluntary signing of the informed consent form was also required.

Exclusion criteria included history of allergies to collagenase, lyase, or other component of the formula; oncological treatment (active or undergone within the last 6 months); concomitant disease (eg, hypertension, lupus, arthritis, epilepsy), homeopathies, or any other condition that might interfere with the treatment; and pregnancy or breastfeeding; as well as treatment with steroids or with systemic immunosuppression, and requirement for surgery or hospitalization during the study.

The criteria for withdrawal of patients from the study included patient decision to withdraw from the research study, failure to attend a visit (with a margin of error of ±1 day from the stipulated visit date), use of another treatment that affects wound healing, nonadherence to application of the treatment as indicated, and pregnancy during the study.

Product description and clinical procedure

The product studied is a microemulsion containing 2 isoenzymes of collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum (r-Clostridium Histolyticum Collagenase H and r-Clostridium Histolyticum Collagenase G, patented as PB220) and hyaluronate r-lyase (patented as PB72K) as active principles. The complete composition of the microemulsion cannot be fully disclosed due to the proprietary nature of the product, although its mechanism of action and functional characteristics are described. The product consists of a protein-rich microemulsion designed to provide a moist, biocompatible environment while delivering bioactive peptides that promote tissue regeneration. This dermatologically tested formulation does not act as a physical barrier or occlusive dressing; rather, it provides a protective interface with the external environment while modulating the wound microenvironment to support healing.

The indications for use are adjunctive therapy in epidermal regeneration processes in wounds. There were no necessary concomitant treatments prescribed together with novel product application. Conventional nonadherent dressing (Adaptic; Solventum), as well as a secondary dressing and bandage for covering the wound area, were used in both groups.

The clinical investigation was undertaken to comply with the requirements of Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices.

The product was applied every 8 hours, spraying it 3 times per wound directly over the affected area. The follow-up time was 7 days (D7), 14 days (D14) and 21 days (D21) after the baseline (D0).

Because the product was used by the participants at home, adherence was carefully monitored during the experimental period, and product tubes were weighed to assess this issue.

Clinical and histological analyses

Wound area was measured at each follow-up visit, as well as on D0. The baseline median area was 40.0 cm² in the intervention group and 36.0 cm² in the control group.

On D0 and D21 of the study, 4-mm biopsies were obtained. Samples were fixed in paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-µm sections with a microtome (RM2245; Leica) for histological analyses. Afterward, cut samples were deparaffinized in xylol and rehydrated with decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Finally, sections were stained with a hematoxylin-eosin and Masson trichrome stain kit (HT15; Sigma-Aldrich).

The analyses of these stainings were done completely blinded, assigning a number to each sample that could not be related to the type of treatment. The newly formed epithelium was measured by capturing high-resolution digital images using a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc) and the Digital Sight DS-2Mu image analysis software (Nikon Instruments Inc). (According to publicly available compatibility lists from Nikon Instruments, the Digital Sight DS-2Mu does not appear among currently supported models. This suggests that the product may be discontinued.)

A 4-point ordinal scoring scale (1, abundant; 2, moderate; 3, scarce; 4, absent) was used to assess the amount of granulation tissue in the sample, layers of epidermis, presence of areas with edema, and presence of blood vessels. Presence of leukocyte infiltration, collagen fiber orientation, collagen fiber arrangement, and overall perception of mature collagen were also determined. Arrangement of collagen fibers was encoded with a numerical scale (1, reticular; 2, mixed; 3, fascicular), and orientation of the fibers another numerical scale (1, vertical; 2, mixed; 3, horizontal).

Dermatology Life Quality Index

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is a well validated and widely used instrument for assessing quality of life in patients with dermatological conditions. The Spanish version of the DLQI consists of 10 items and covers a time frame of the last 7 days. Each question includes a Likert-type scale with 4 possible responses: 3, very much; 2, a lot; 1, a little; and 0, not at all, along with a fifth response option, “not applicable.” The health dimensions assessed include symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and/or study, personal relationships (including sexuality), and treatment. The final score is obtained by adding the scores of each item, ranging from 0 (minimal impact) to 30 points (maximum impact). Each patient was asked to complete the DLQI at the baseline visit (D0) and again once the wound had fully reepithelialized (if applicable) or at the end of the study.

Product satisfaction survey

The product satisfaction survey is a measurement based on ordinal, subjective variables. It considers parameters related to satisfaction with treatment outcomes from both the patient’s and the health care provider’s perspectives. Responses are expressed as polytomous variables—ie, intensity rated as mild, moderate, or severe; causality as not related, possible, probable, or causal relationship; and severity as yes/no.

Pain assessment

To evaluate the safety of using the product on open wounds, the pain experienced by the patient was assessed at baseline (D0) and at each follow-up visit (D7, D14, and D21) using the visual analog scale (VAS), the most frequently used method for pain assessment. This scale consists of a 100-mm (10-cm) line that represents a continuous spectrum of pain experience. Descriptions appear only at the end points, from “no pain” at one end to “the worst pain imaginable” at the other, with no other markers along the line. The VAS is a simple, robust, sensitive, and reproducible tool, making it useful for reassessing pain in the same patient at different times. Its validity for measuring experimental pain has been demonstrated in numerous studies, and its reliability has also been evaluated, showing satisfactory results.16–19

Adverse effects assessment

For safety evaluation, signs and symptoms corresponding to adverse events during the clinical study were recorded during visits. These records contain information on the nature, severity, onset time, and duration of adverse events; the actions taken to counteract these events; and the likelihood of their association with the study treatment according to the Karch and Lasagna causality assessment criteria,20 along with any other relevant details.

Statistical analyses

Prior to analysis, data distributions were assessed for normality to guide the selection of appropriate statistical methods. The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to each variable to evaluate conformity to a normal distribution. For variables that did not meet the normality assumption, nonparametric methods were applied; normally distributed variables were analyzed using parametric tests.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all primary variables to summarize central tendency and dispersion. Mean, median, standard deviation, first quartile (Q1) and third quartile (Q3), and IQR were reported for continuous variables to provide a comprehensive overview.

To evaluate the efficacy of the novel serum relative to standard care, several statistical tests were conducted based on data distribution characteristics. The Mann-Whitney U test was used, as nonparametric for nonnormally distributed variables, to assess median differences between groups. This was particularly useful for outcomes like granulation tissue formation scores, where data often did not follow a normal distribution. For within-group comparisons over time, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was applied to assess changes in wound healing metrics, such as wound size reduction from baseline to final assessment, within each group independently. This nonparametric test accommodates paired data and is appropriate for evaluating changes in nonnormally distributed variables over time.

All hypothesis tests were 2-tailed, with the significance level set at P < .05 (95% CI). Exact P values were reported when available. All analyses were conducted using Python and R software (version 4.3.1; The R Project for Statistical Computing). The SciPy library in Python was utilized for nonparametric tests, including the Mann-Whitney U and Wilcoxon signed rank tests. Shapiro-Wilk normality tests were performed using scipy.stats.shapiro (The SciPy community).

This combination of advanced statistical studies provided a rigorous statistical framework to evaluate the effect of the novel product on chronic wound healing outcomes.

Results

This study targeted subjects with open wounds of different origins. The intervention group was treated with the novel product, which was applied directly to the wound for 21 days, in addition to the habitual clinical practice, whereas care for the control group followed only the habitual clinical practice during the same period. Both groups received conventional dressing.

The primary end point of the study was to assess the effect of the intervention on wound area reduction. Healing progression (including epithelialization and neovascularization) and pain reduction were secondary end points.

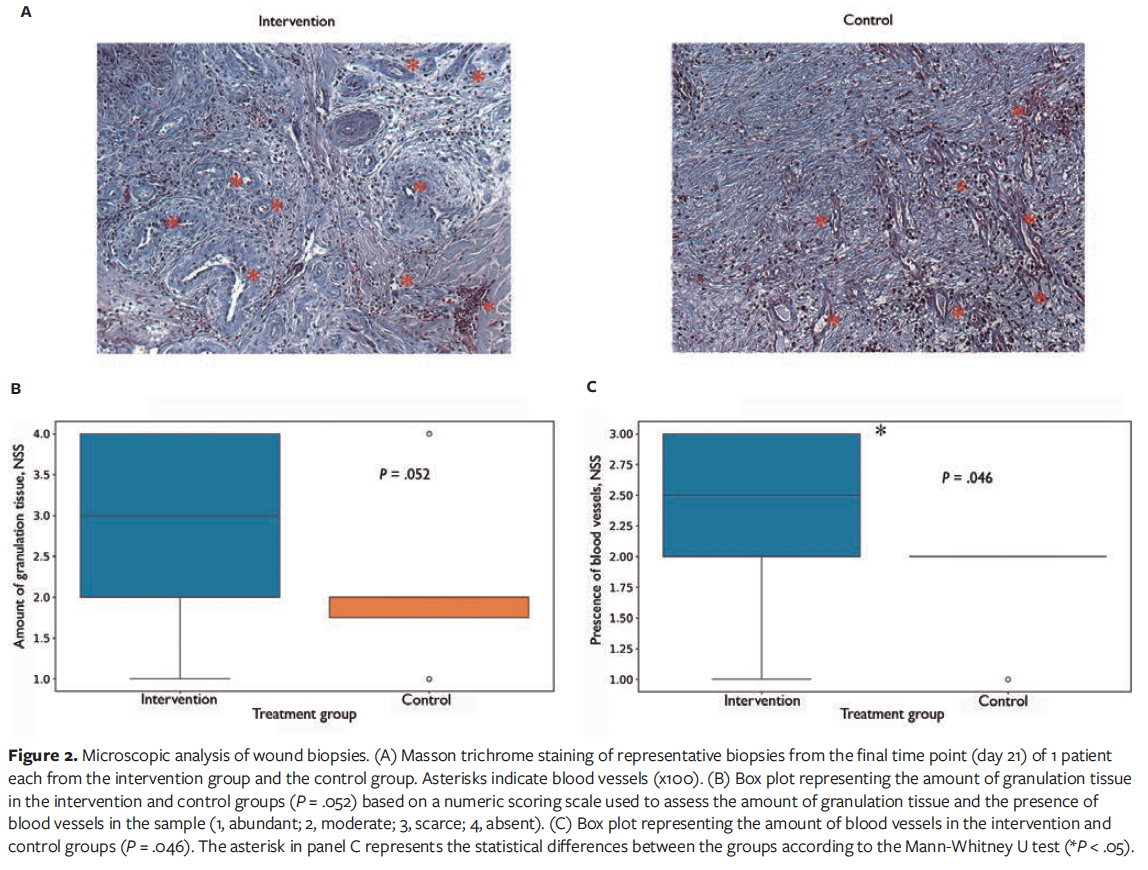

The histopathological evaluation of the biopsies included analysis of wound reepithelialization, the orientation and arrangement of collagen fibers, the amount of collagen present, the granulation of the samples, and the presence and quantity of blood vessels. Biopsy specimens obtained at the start and end of the study demonstrated increased histological improvements in the intervention group.

Epithelialization outcomes

The evaluation of wound reepithelialization was assessed at several intervals throughout the study: D7, D14, and D21. There was a marked increase in the degree of epithelialization over time in both groups, although it did not reach statistical significance among groups at any time point. In the intervention group, the mean epithelialization at baseline (D0) was 45.53%, increasing to 65.87% by D21, showing a 45% improvement (absolute variation, P = .0099). In the intervention group, 79% of patients showed substantial improvement by the end of the study. In the control group, the mean epithelialization increased from 43.21% at baseline (D0) to 66.29% by D21, indicating a 53% improvement (P = .0041). In both groups, 100% of patients showed improvement by D14, and 100% by D21 (linear mixed-effects models, data not shown).

Regarding layers of epidermis, the intervention group showed a 17% improvement in wound epithelialization, compared with only 7% in the control group. However, these differences detected between the intervention and control groups were not statistically significant at any time point, as analyzed by the Wilcoxon test (data not shown).

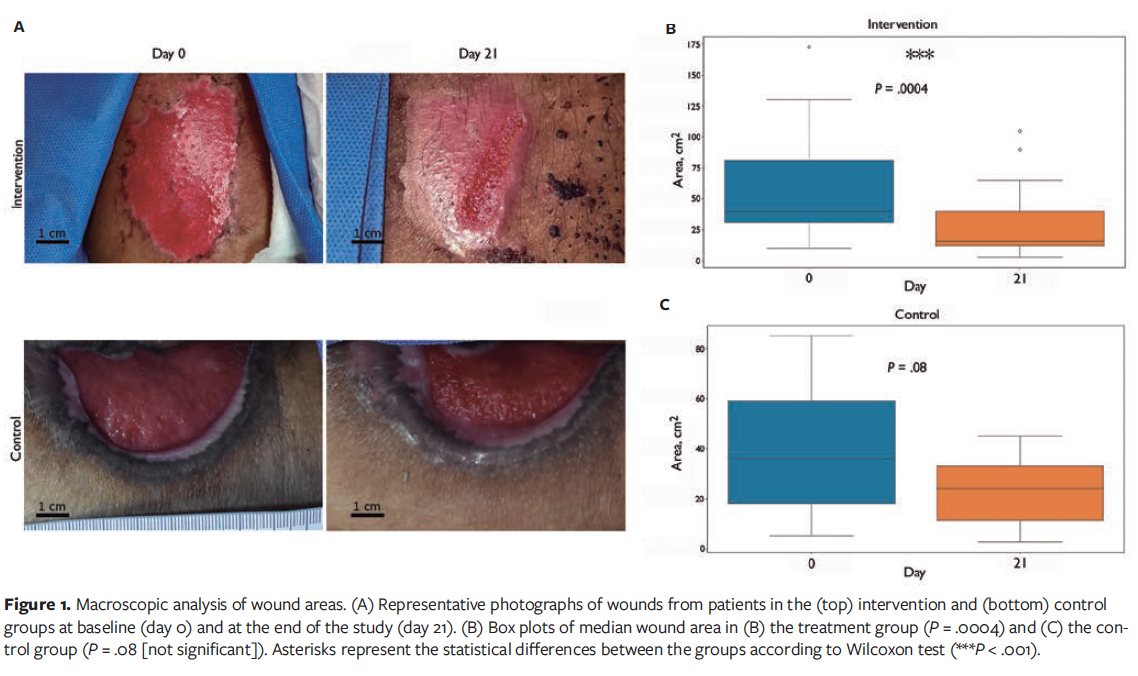

Wound area reduction

The intervention group exhibited a significantly greater reduction in wound area compared to the control group. Figure 1A shows representative photographs of patients in the intervention and control groups at the start and the end of the study. At baseline (D0), the intervention group had a median wound size of 40.0 cm² (Q1, 31.24 cm² and Q3, 81.0 cm²), which reduced to 16.0 cm² by the end of the study (Q1, 12.0 cm² and Q3, 40.0 cm²), corresponding to a significant reduction of 60% (P = .0004) (Figure 1B). The control group showed a smaller reduction, from a median of 36 cm² (Q1, 18.0 cm² and Q3, 59.0 cm²) to 24 cm² (Q1, 11.25 cm² and Q3, 33.0 cm²) (P = .08), achieving only a 33.3% reduction (Figure 1C). Only 1 patient, in the intervention group, achieved complete healing before 21 days.

Histopathological evaluation

Regarding the arrangement and orientation of collagen fibers, there were no statistical differences between groups (Figure 2A).

An increase was observed in granulation tissue formation in the intervention group, approaching significance (P = .052). These data suggest a trend toward increased granulation tissue generation in the novel product-treated samples, although they do not meet conventional thresholds for statistical significance (Figure 2B).

Angiogenesis was statistically more pronounced in the intervention group, with a higher number of newly formed blood vessels observed (Figure 2C). This was quantified using the numeric scoring system described in the “Clinical and histological analyses” section above, showing a median angiogenesis score of 2.5 in the intervention group compared with 2.0 in the control group (P = .046). These findings suggest enhanced angiogenic activity, which may contribute to the improved wound healing observed.

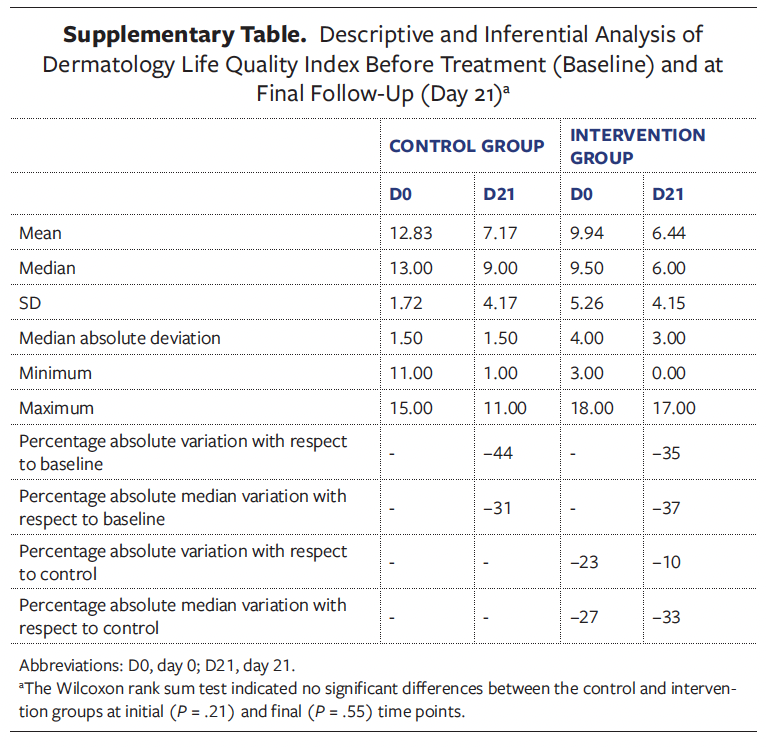

Dermatology Life Quality Index

Both groups reported improvements at the end of the study as compared with the initial time point, as observed in the DLQI scores, which measure the effect of skin diseases on patient quality of life. However, these improvements were not statistically significant between groups (Supplementary Table).

Pain assessment

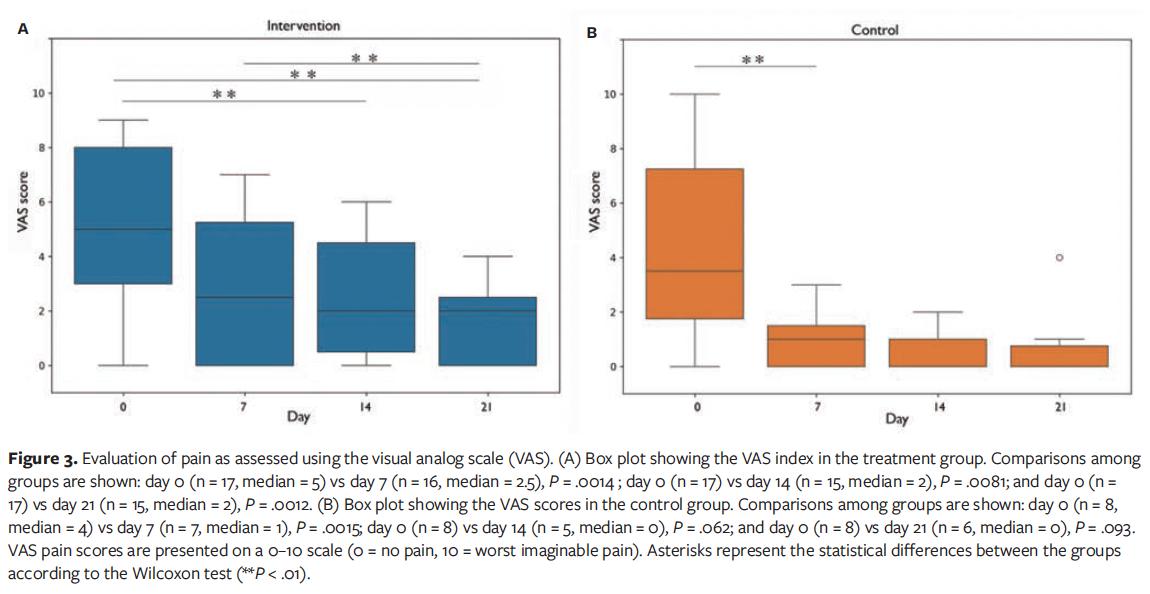

Pain levels were assessed using the VAS. Both groups experienced reductions in pain, although the intervention group reported a higher decrease. In the treatment group who received the novel product, there was a significant improvement in VAS score at D7, D14, and D21 compared with the D0 score, whereas in the control group the only significant improvement occurred from D0 to D7 (Figure 3).

Safety and adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported in either group. The use of the novel product was well tolerated, and no participants experienced significant side effects related to it. Two patients reported mild itching and irritation at a specific time point, but these effects were not considered clinically significant and resolved spontaneously without any additional medical treatment. These reported adverse events fall within the expected group of consequences associated with chemical peel and are recorded in the product’s instructions for use.

Satisfaction

Both patients and clinicians reported high levels of satisfaction with the novel treatment. The intervention group patients rated the product as highly effective, and clinicians indicated they would recommend its use in future treatments.

All intervention group patients expressed a general preference for the product, including its appearance and ease of application on the skin. Additionally, 94% of these patients reported liking the product’s scent, while 88% appreciated the sensation it provided on the wound. All patients in the intervention group agreed that using the product led to improvements in scar appearance, elasticity, pigmentation, color, and size.

After the treatment, the clinicians were completely satisfied with the product’s appearance and ease of application. The product’s aroma, its contribution to reducing wound healing time, the enhancement of wound appearance, and its overall tolerance were rated as satisfactory by the clinicians in 94% of cases.

Discussion

Chronic wounds often remain stalled in the inflammatory phase due to inadequate treatment and underlying comorbidities, resulting in prolonged healing times.21 Although various dressings (films, sponges, hydrogels, powders) have been developed to enhance healing by maintaining a moist environment and promoting angiogenesis,22 traditional dressings often do not actively modulate the wound microenvironment, maintain antimicrobial action, or ensure optimal moisture.23 As research continues to evolve, the integration of other strategies alongside traditional dressings presents a promising frontier in enhancing the efficacy of treatments for chronic cutaneous ulcers.24

Optimizing the wound bed may reduce hospital stay.25 This approach involves the ECM, mainly composed of collagen and hyaluronic acid (HA), which provides structural and biochemical cues vital to cellular function and migration.26–28 Clinical decisions are guided by the TIME principles—that is, tissue debridement, infection control, moisture balance, and edge management.29 Because methods such as surgical debridement are not always feasible, novel agents may serve as valuable alternatives.

The current study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the novel product in enhancing wound healing vs conventional dressing. This product combines hyaluronate lyase, which degrades HA and promotes angiogenesis, with collagenases G and H, which are able to remove damaged tissue and support fibroblast activity, thus providing a powerful combined action.

Hyaluronate lyase has shown significant stability across pH and temperature ranges, thereby enhancing its therapeutic versatility.26 HA degradation has been associated with reduced fibrotic scarring; it may inhibit matrix cells responsible for scar formation, thus creating a favorable environment for scarless tissue repair in fetal healing models.5

Collagen degradation is essential for effective wound healing and tissue remodeling.30 The action of collagenase influences the balance between collagen synthesis and degradation, which is critical in preventing pathological scarring and ensuring proper wound closure.13 By regulating fibroblast activity, collagenase enhances the overall remodeling of the ECM, enabling effective healing responses and minimizing the risk of chronicity in cutaneous ulcers.31

Collagenase G has a preference for cleaving the alpha-1 and alpha-2 chains of collagen.30,32 It acts on native collagen, destabilizing the fibers and facilitating the activity of other enzymes. Collagenase H is more effective in breaking tertiary bonds in more compact collagen fibers. It complements the action of collagenase G by targeting deeper bonds, degrading collagen into smaller fragments. Therefore, both collagenases work synergistically for efficient collagen digestion: collagenase G initiates the process, and collagenase H completes the fragmentation.30,32

The combined application of hyaluronate lyase and recombinant collagenases G and H in the present study is associated with a faster reduction in wound areas. This study indicates that patients receiving the novel product combined with dressings experienced significantly shorter healing times compared with the control group, with complete healing within 21 days reported in 1 patient in the intervention group.

Although the sample size was limited by the number of patients that could be recruited during the established period, a rigorous methodology was used to ensure the quality of data and analysis. The chosen research protocol adhered to established standards and guidelines, drawing from a recommended and previously employed protocol within the same time frame as other studies. In this study, follow-up was conducted at various time points over a 21-day period, when the proliferative phase is expected to take place. This phase is characterized by the formation of granulation tissue and new blood vessels, together with the initiation of epithelialization.4,33,34 The current study shows a trend toward increased granulation tissue formation in the intervention group. However, further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm this potential effect. This trend may indicate that treatment with the novel product supports granulation tissue development, contributing to wound repair by creating a supportive matrix for new tissue formation. This effect can be attributed to collagenase, which facilitates the removal of necrotic tissue, allowing for the regeneration of healthy granulation tissue and the formation of new ECM components.

Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the breakdown of HA by lyase enzymes reduces the viscosity of the ECM, promoting better diffusion of nutrients and enabling the formation of granulation tissue.5,26,33–35

The degradation of high-molecular-weight HA by hyaluronate lyase generates low-molecular-weight HA, which can activate intracellular signaling pathways. This, together with the reduced viscosity, promotes cell migration and proliferation of fibroblasts and endothelial cells, processes that are essential for angiogenesis.36

In this regard, different studies have pointed to an ability of hyaluronate lyase to enhance angiogenesis, because its action on HA can also lead to the release of proangiogenic growth factors and cytokines. Moreover, the lyase enzyme’s role in angiogenesis arises from its ability to influence endothelial cell behaviors essential for vessel formation.36 The present study corroborates this action, because the intervention group presented increased vascularization compared with the control group. Angiogenesis typically occurs during the proliferative phase, developing new blood vessels from preexisting ones for oxygen and nutrient delivery, which is essential to wound repair.5 This finding highlights the angiogenic potential of the novel product, suggesting that it may facilitate healing by promoting vascularization within the wound bed, among other mechanisms of action.

The degradation products of HA by hyaluronate lyase can also participate in signaling pathways that regulate interaction with the ECM components, thereby influencing tissue architecture and function.37 HA has a strong ability to retain water on the wound surface, which can prevent dryness of injured sites and promote faster healing. Moreover, HA has anti-inflammatory properties that also contribute to faster and more effective healing. HA allows debridement in hypertrophic scars and inhibits the increase of tumor growth factor β, an important factor in fibrosis. This decreases the inflammatory response in wounds (another factor contributing to fibrosis) and reduces the formation of erratic collagen fibers, allowing them to organize and distribute in healthy tissue patterns.38,39

Similarly, collagenases have been effective in debridement, removing necrotic tissue, and promoting a healthy wound bed, dermal cell migration, and reepithelialization.30 Although in the present study no significant differences in epithelialization were observed between the intervention and control groups at any time point, both groups demonstrated a marked progression in this process over time. Interestingly, multiple layers of regenerated epidermis were more frequently observed at the wound site in the intervention group compared with controls, indicating early epidermal stratification and reepithelialization. While this difference was not statistically significant, it suggests a biologically relevant trend toward enhanced epidermal regeneration in the treated group.

Other studies conducted in vivo further validated collagenase’s capacity to promote granulation tissue formation, collagen deposition, new blood vessel growth, and reepithelialization.40,41 These effects collectively accelerate the healing process without triggering an immune reaction.40,41

It has been highlighted that collagenase facilitates the removal of debris obstructing healing, simultaneously reducing bacterial load. In particular, this ability to manage biofilm and bacterial load further underscores the potential of these enzymes in improving clinical outcomes.42 Moreover, the novel product evaluated in the present study forms a film over the wound, thereby effectively reducing the risk of infection. For this reason, its formulation does not include any antiseptic or antibiotic agent, thus avoiding potential interference with the enzymatic activity and minimizing the risk of systemic side effects.

Both groups in the current study experienced decreases in pain, with the intervention group showing a greater reduction than the control group. The intervention group demonstrated a significant improvement in VAS score at D7, D14, and D21 compared with D0, whereas the control group only showed a significant improvement from D0 to D7. This lack of significance could be attributed to the smaller sample size in the control group at these time points, which limits the statistical power. Beyond statistical significance, it is established that clinical relevance for pain reduction can be assessed by using the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 1.3 cm on the VAS.43 Gallagher et al43 prospectively validated that a change of approximately 1.3 cm (95% CI, 1.0 cm-1.6 cm) in acute pain on a 10-cm VAS represents the MCID perceived by patients as a real improvement. Although this threshold was derived from acute pain populations, it has been widely cited in chronic wound research as a benchmark. Importantly, in the current study, 94% of patients in the treatment group and 50% of patients in the control group exceeded this threshold at least once during follow-up, a clinically meaningful result. Moreover, while changes in the control group were not statistically significant, some of these patients still experienced clinically meaningful improvements in pain perception.

The safety profile of lyase and collagenases G and H, particularly in clinical applications, is an important consideration due to their biological activity and potential interactions with other substances. These enzymes are generally well-tolerated by patients, with their safety and tolerability affirmed in various studies and confirmed in this study at the concentrations used in the novel product. Because these enzymes are well-tolerated by patients, they have minimal adverse effects, which is crucial for patient adherence in chronic wound management.27,44

Overall, the most important findings of this study lie in the accelerated wound area reduction and enhanced angiogenesis achieved with novel product treatment, along with a trend toward increased granulation. These results underscore the efficacy of this product as a therapeutic intervention in chronic wound management, by revascularizing compromised tissue and contributing to accelerated healing outcomes.

These insights suggest that effective treatment of chronic cutaneous ulcers may benefit from incorporating advancements in therapeutic interventions, including recombinant collagenases and hyaluronate lyase enzymes, to enhance healing processes and optimize patient outcomes. Remarkably, there is only one US Food and Drug Administration-approved product containing collagenase for use in dermal and burn wounds in the United States.45

The evidence from the current study showcases the potential advantages of the novel product over the traditional dressing and supports further investigation into this product as a viable strategy for enhancing wound vascularization and promoting recovery in chronic, nonhealing wounds.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sample size was limited by the number of patients that could be recruited during the established period. Future research with a larger sample size could enhance the generalizability of these findings and allow for a deeper exploration of subgroup variations. Additionally, there was an imbalance in number of patients in each group studied; however, careful statistical adjustments were made to account for this variation. Heterogeneity in outcome hinders the possibility to make meaningful comparisons between groups in some variables, and these should be analyzed in future studies. The duration of wound evolution prior to patient enrollment was not systematically recorded; however, all wounds were clinically classified as chronic by the attending physicians. Future studies should also consider including a control group treated with the emulsification vehicle without the active enzymatic agents in order to isolate and accurately assess the specific contribution of the active components to the observed clinical effects. Moreover, studies with longer experimental times may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the product’s effects on long-term wound healing, including its effectiveness in promoting complete healing and its potential positive effect on the formation of fibrotic scars. Overall, these limitations suggest avenues for future research that could build on these findings and extend their applicability.

Conclusion

The combination of collagenases G and H as well as hyaluronate lyase enzymes used in the novel product studied promoted improvement in angiogenesis and wound healing in chronic cutaneous ulcers in comparison with conventional dressings. According to patient and clinician satisfaction questionnaires, use of the product improved the appearance, elasticity, pigmentation, color, and size of the scar; they also appreciated the ease of application. Moreover, the product demonstrated clinical safety throughout the study, without remarkable side effects.

In this study, the combined action of recombinant collagenases G and H as well as hyaluronate lyase present in the product demonstrated a combined effect, addressing different facets of the wound healing process. The product created an optimal environment for healing chronic cutaneous ulcers, making it a potent therapeutic option in regenerative medicine. Future studies with a larger sample size, a control group treated with the emulsification vehicle without the active enzymatic agents, and longer follow-up are needed to further consolidate and strengthen the evidence supporting the outcomes described in this work.

Author & Publication Information

Authors: Jorge Adrián Garza-Cerna, MD, MSc1; Gabriel Ángel Mecott-Rivera, MD, PhD¹; Yanko Castro-Govea, MD, PhD¹; José Juan Pérez-Trujillo, PhD²; Roberto Montes de Oca-Luna, MD, PhD²; Daniel Salas-Treviño, PhD³; Valeria Kopytina, PhD⁴; and Jorge López Berroa, MD⁴

Affiliations: 1Plastic, Aesthetic, and Reconstructive Surgery Service, University Hospital “Dr. José Eleuterio González,” Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico; 2Department of Histology, Faculty of Medicine, Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico; 3Infectiology Service, University Hospital “Dr. José Eleuterio González,” Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico; 4Proteos Biotech Laboratories, Madrid, Spain

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Guadalupe T. González-Mateo, Rubén Lopez-Aladid, and Javier Carrero from Premium Research for writing support.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, writing, and original draft preparation: V.K. and J.L.B. Assessment of clinical measurements and patient follow-up: J.A.G.-C. Supervision of clinical management and patient follow-up: Y.C.-G. and D.S.-T. Final manuscript review and editing: All authors.

Disclosure: V.K. and J.L.B. are employees of Proteos Biotech. Their affiliation did not influence the data collection, statistical analysis, or interpretation of the study results. The other authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University Hospital “Dr. José Eleuterio González,” in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed written informed consent forms, and the study complied with all applicable clinical and data protection regulations.

Correspondence: Jorge López Berroa, MD, Pbserum office, Avenida de la Osa Mayor, 4, 28023, Madrid, Spain; jorge.lopez@proteosbiotech.com

Manuscript Accepted: August 11, 2025

Recommended Citation

Recommended Citation: Garza-Cerna JA, Mecott-Rivera GA, Castro-Govea Y, et al. Use of a novel debriding agent based on collagenase and hyaluronate lyase to enhance angiogenesis, stimulate healing, and reduce pain in chronic cutaneous wounds. Wounds. 2025;37(10):397-408. doi:10.25270/wnds/24209

References

1. Falanga V, Isseroff RR, Soulika AM, et al. Chronic wounds. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):50. doi:10.1038/s41572-022-00377-3

2. Olsson M, Järbrink K, Divakar U, et al. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: a systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27(1):114-125. doi:10.1111/wrr.12683

3. Sen CK. Human wound and its burden: updated 2020 compendium of estimates. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2021;10(5):281-292. doi:10.1089/wound.2021.0026

4. Hua Y, Bergers G. Tumors vs. chronic wounds: an immune cell’s perspective. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2178. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02178

5. Jung H. Hyaluronidase: an overview of its properties, applications, and side effects. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47(4):297-300. doi:10.5999/aps.2020.00752

6. Markiewicz-Gospodarek A, Kozioł M, Tobiasz M, Baj J, Radzikowska-Büchner E, Przekora A. Burn wound healing: clinical complications, medical care, treatment, and dressing types: the current state of knowledge for clinical practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1338. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031338

7. Simms KW, Ennen K. Lower extremity ulcer management: best practice algorithm. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(1-2):86-93. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03431.x

8. Avila-Rodríguez MI, Meléndez-Martínez D, Licona-Cassani C, Manuel Aguilar-Yañez J,

Benavides J, Lorena Sánchez M. Practical context of enzymatic treatment for wound healing: a secreted protease approach (review). Biomed Rep. 2020;13(1):3-14. doi:10.3892/br.2020.1300

9. Berwick D, Young L, Lee A, Lancaster D, Dheansa B. Local anaesthesia for enzymatic debridement of cutaneous burns: a prospective analysis of 27 cases. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2023;36(1):74-78.

10. Nowak M, Mehrholz D, Barańska-Rybak W, Nowicki RJ. Wound debridement products and techniques: clinical examples and literature review. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2022;39(3):479-490. doi:10.5114/ada.2022.117572

11. Hawthorne B, Simmons JK, Stuart B, Tung R, Zamierowski DS, Mellott AJ. Enhancing wound healing dressing development through interdisciplinary collaboration. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2021;109(12):1967-1985. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.34861

12. Alvarez O, Fernandez-Obregon A, Rogers RS, Bergamo L, Masso J, Black M. A prospective, randomized, comparative study of collagenase and papain-urea for pressure ulcer debridement. Wounds. 2002;14(8):293-301.

13. Ghofrani A, Hassannejad Z. Collagen-based therapies for accelerated wound healing. In: Maj MC, Ikolo F, eds. Cell and Molecular Biology - Annual Volume 2024 [Working Title]. IntechOpen; 2024. doi:10.5772/intechopen.1004079 https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/89478

14. Li F, Xu D. Functional role of R462 in the degradation of hyaluronan catalyzed by hyaluronate lyase from Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Mol Model. 2015;21(8):196. doi:10.1007/s00894-015-2724-z

15. Regulations of the General Health Law Regarding Health Research (Mexico). Official Gazette of the Federation. Published January 6, 1987. Updated February 4, 2014. https://clinregs.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/mexico/HlthResRegs-GoogleTranslation.pdf

16. Duncan JAL, Bond JS, Mason T, et al. Visual analogue scale scoring and ranking: a suitable and sensitive method for assessing scar quality? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(4):909-918. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000232378.88776.b0

17. Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983;17(1):45-56. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(83)90126-4

18. Yarnitsky D, Sprecher E, Zaslansky R, Hemli JA. Multiple session experimental pain measurement. Pain. 1996;67(2-3):327-333. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(96)03110-7

19. Haefeli M, Elfering A. Pain assessment. Eur Spine J. 2006;15 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S17-S24. doi:10.1007/s00586-005-1044-x

20. Karch FE, Lasagna L. Toward the operational identification of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;21(3):247-254. doi:10.1002/cpt1977213247

21. Shi S, Wang L, Song C, Yao L, Xiao J. Recent progresses of collagen dressings for chronic skin wound healing. Collagen and Leather. 2023;5(1):31. doi:10.1186/s42825-023-00136-4

22. Onesti MG, Fioramonti P, Carella S, Fino P, Sorvillo V, Scuderi N. A new association between hyaluronic acid and collagenase in wound repair: an open study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(2):210-216.

23. Roehrs H, Stocco JG, Pott F, Blanc G, Meier MJ, Dias FA. Dressings and topical agents containing hyaluronic acid for chronic wound healing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;7(7):CD012215. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012215.pub2

24. De Francesco F, De Francesco M, Riccio M. Hyaluronic acid/collagenase ointment in the treatment of chronic hard-to-heal wounds: an observational and retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(3):537. doi:10.3390/jcm11030537

25. Saap LJ, Falanga V. Debridement performance index and its correlation with complete closure of diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10(6):354-359. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475X.2002.10603.x

26. Ebraheem MA, El-Fakharany EM, Husseiny SM, Mohammed FA. Purification and characterization of the produced hyaluronidase by Brucella Intermedia MEFS for antioxidant and anticancer applications. Microb Cell Fact. 2024;23(1):200. doi:10.1186/s12934-024-02469-z

27. Fino P, Chello C, Latini C, et al. The combination of hyaluronic acid and collagenase in the treatment of skin ulcers: an open, multicenter clinical study assessing safety and tolerability of Bionect Start®. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2024;28(7):2894-2905. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202404_35920

28. Longinotti C. The use of hyaluronic acid based dressings to treat burns: a review. Burn Trauma. 2014;2(4):162-168. doi:10.4103/2321-3868.142398

29. Bowers S, Franco E. Chronic wounds: evaluation and management. Am Family Phys. 2020;101(3):159-166.

30. Alipour H, Raz A, Zakeri S, Dinparast Djadid N. Therapeutic applications of collagenase (metalloproteases): a review. Asian P J Trop Biomed. 2016;6(11):975-981. doi:10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.07.017

31. Toriseva MJ, Ala-aho R, Karvinen J, et al. Collagenase-3 (MMP-13) enhances remodeling of three-dimensional collagen and promotes survival of human skin fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(1):49-59. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700500

32. Bauer R, Wilson JJ, Philominathan STL, Davis D, Matsushita O, Sakon J. Structural comparison of ColH and ColG collagen-binding domains from Clostridium histolyticum. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(2):318-327. doi:10.1128/JB.00010-12

33. Cabral-Pacheco GA, Garza-Veloz I, Castruita-De la Rosa C, et al. The roles of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in human diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9739. doi:10.3390/ijms21249739

34. Frangogiannis NG. Fibroblast-extracellular matrix interactions in tissue fibrosis. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2016;4(1):11-18. doi:10.1007/s40139-016-0099-1

35. Buhren BA, Schrumpf H, Hoff NP, Bölke E,

Hilton S, Gerber PA. Hyaluronidase: from clinical applications to molecular and cellular mechanisms. Eur J Med Res. 2016;21:5. doi:10.1186/s40001-016-0201-5

36. Liu M, Tolg C, Turley E. Dissecting the dual nature of hyaluronan in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019;10:947. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00947

37. Salih ARC, Farooqi HMU, Amin H, Karn PR, Meghani N, Nagendran S. Hyaluronic acid: comprehensive review of a multifunctional biopolymer. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2024;10(1):63. doi:10.1186/s43094-024-00636-y

38. Aduba DC, Yang H. Polysaccharide fabrication platforms and biocompatibility assessment as candidate wound dressing materials. Bioengineering (Basel). 2017;4(1):1. doi:10.3390/bioengineering4010001

39. Petrey AC, de la Motte CA. Hyaluronan, a crucial regulator of inflammation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:101. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00101

40. Chen J, Gao K, Liu S, et al. Fish collagen surgical compress repairing characteristics on wound healing process in vivo. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(1):33. doi:10.3390/md17010033

41. Helary C, Abed A, Mosser G, et al. Evaluation of dense collagen matrices as medicated wound dressing for the treatment of cutaneous chronic wounds. Biomater Sci. 2015;3(2):373-382. doi:10.1039/c4bm00370e

42. Breite AG, McCarthy RC, Dwulet FE. Characterization and functional assessment of Clostridium histolyticum class I (C1) collagenases and the synergistic degradation of native collagen in enzyme mixtures containing class II (C2) collagenase. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(9):3171-3175. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.09.059

43. Gallagher EJ, Liebman M, Bijur PE. Prospective validation of clinically important changes in pain severity measured on a visual analog scale. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38(6):633-638. doi:10.1067/mem.2001.118863

44. Singh B, Sims H, Trueheart I, et al. A Phase I clinical trial to assess safety and tolerability of injectable collagenase in women with symptomatic uterine fibroids. Reprod Sci. 2021;28(9):2699-2709. doi:10.1007/s43032-021-00573-8

45. McCallon SK, Weir D, Lantis JC II. Optimizing wound bed preparation with collagenase enzymatic debridement. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2015;6(1-2):14-23. doi:10.1016/j.jccw.2015.08.003