Patient-Reported Outcomes Favor Below-Knee Over Above-Knee Amputation in Patients With Nontraumatic Lower Extremity Wounds

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Below-knee amputation (BKA) and above-knee amputation (AKA) are often last-resort treatment options for chronic lower extremity (LE) wounds. Objective. To compare, for the first time, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in patients who underwent BKA or AKA for nontraumatic chronic LE wounds. Methods. PROMs (20-item Self-Reporting Questionnaire [SRQ-20], Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Pain Intensity 3-item scale [PROMIS-3a], Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale [CD-RISC], and Lower Extremity Functional Scale [LEFS]) were collected for patients who underwent AKA or BKA and who presented to a tertiary wound center between June 2022 and October 2024. Mental well-being (SRQ-20), pain intensity (PROMIS-3a), resilience (CD-RISC), and function (LEFS) were measured at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years postoperative. Results. Of 96 patients, 22 (22.9%) underwent AKA and 74 (77.1%) underwent BKA. Significant differences were observed between patients who underwent AKA versus BKA in mean (SD) overall function (LEFS, 33.9 [13.7] vs 47.4 [25.2]; P = .003), psychological distress (SRQ-20, 5.6 [4.3] vs 3.1 [3.9]; P = .002), and pain intensity (PROMIS-3a, 58.9 [10.4] vs 48.2 [13]; P = .001). Conclusion. The study results indicate that patients who have undergone AKA have higher pain intensity, more psychological distress, and lower function compared with patients who have undergone BKA. These findings underly the importance of performing a BKA when possible.

Major lower extremity amputation (MLEA) is generally considered a last resort for nonhealing leg wounds; it is performed with the goal of restoring ambulatory function and prior quality of life (QOL). In choosing the optimal level of amputation above the ankle, the physician relies on a multitude of unique characteristics to ensure the most beneficial outcome. Despite advancements in surgical techniques and limb salvage protocols, 5-year mortality rates following MLEA remain high.1 When stratified by amputation level, the 5-year mortality risk is substantially higher following above-knee amputation (AKA) compared with below-knee amputation (BKA).2 It is important to distinguish that mortality following BKA or AKA primarily reflects the underlying disease or diseases leading to the amputation, rather than the amputation itself. Despite this disparity in mortality, BKA and AKA rates remain nearly identical for nontraumatic lower extremity (LE) amputations.3 Due to the high morbidity and mortality rates following any MLEA, all aspects of the decision-making and rehabilitation processes must be thoroughly studied to optimize surgical approach and recovery.

Surgical complications, wound healing, and reamputation rates following BKA and AKA are well studied.4 Outside of these traditional postoperative end points, there is a lack of patient-

reported outcome measures (PROMs) in this comorbid patient population. PROMs are validated self-reported measurements of a patient’s health condition, functional status, or mental behavior that provide further insight into the patient’s recovery beyond objective metrics.5,6 PROMs are particularly important in the MLEA population because of the immense effect of MLEA on QOL and because of the causes of functional limb amputation. PROMs provide insight into how an amputee perceives their new function and pain, among other QOL measures, as they navigate through recovery. Traditional clinical research otherwise fails to capture these patients’ perception of their recovery.

Recently, there has been a concerted effort to incorporate PROMs into clinical research across all specialties to help guide and enhance decision-making.7 In the MLEA population, PROMs can help physicians analyze patients’ recovery by assessing ambulatory values, mental health scores, and expectations postoperatively. This then allows physicians to adjust postoperative care accordingly. Although significant morbidity and mortality within the MLEA population is well-

documented, there is a lack of QOL and functional research in the population undergoing AKA versus BKA.

This is the first study to compare PROMs in patients who underwent BKA or AKA for nontraumatic chronic LE wounds. The PROMs used in the current study are the 20-item Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20), the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Pain Intensity 3-item scale (PROMIS-3a), the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), and the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS).

Methods

Study design

After institutional review board deemed this study exempt, a cross-sectional study was conducted at the authors’ Center for Wound Healing between June 2022 and October 2024. Patients who underwent either BKA or AKA for chronic LE wounds, defined as wounds not progressing toward healing within 4 weeks of standard care, were included. Senior authors (C.E.A., R.C.Y.) performed all procedures with consistent techniques. Further inclusion criteria were patients aged 18 years and older, those who had undergone BKA or AKA in the past 6 years (2019-2024), and those who completed all questions in at least 1 survey set from 1 month to 5 years postoperatively.

Data collection

Patient characteristics, preoperative factors, wound history, surgical techniques, and postoperative outcomes were gathered from electronic medical records. Demographics included age, sex, race, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus (DM), and other comorbidities. Race was included in this study to investigate if disparities in perceived recovery exist between races. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated to quantify comorbidity burden.8 Patients were classified by the highest level of amputation in either leg.

PROMs

PROMs were emailed to patients 4 days before their clinic appointments. For incomplete surveys, reminders for survey completion were sent 1 day prior to the appointment. QR codes linking to the PROMs were displayed in clinic rooms and waiting areas. PROMs were attributed to visits at 1-, 3-, and 6-month and 1-, 3-, and 5-year intervals postoperatively. Pain and function were evaluated using the PROMIS-3a and the LEFS, respectively. Psychological distress was evaluated using the SRQ-20. Resiliency was assessed using the CD-RISC.

The PROMIS-3a measured current, average, and worst pain over the past 7 days, with higher T-scores indicating greater pain intensity.9 Scores were reported as normalized T-scores based on a reference mean of 50 and a SD of 10, with higher scores indicating more pain. The LEFS assesses functional ability in daily tasks, with each question rated from 0 to 4 based on difficulty of completion (0 = “extreme difficulty or unable to perform activity,” and 4 = “no difficulty”).10 The total raw score for the 20-item LEFS ranges from 0 to 80, with lower scores indicating more disability.10 The percentage of maximal function was obtained by summing the responses, multiplying by 100, and dividing by the maximum raw score of 80. The SRQ-20, developed by the World Health Organization, was used in paper form for independent patient completion.11 The SRQ-20 uses a “yes” or “no” format to detect psychological distress within the last 30 days (“yes” = 1, and “no” = 0). The total “yes” responses yield a maximum score of 20, with scores of 8 or above indicating the need for further mental health evaluation.11 The SRQ-20 was selected for its psychometric validity and suitability for self-administration. The CD-RISC quantifies resilience by generating a raw score from 25 items, which patients rank on a scale of 0 to 4 based on resistance to potential QOL disruption (0 = “not true at all,” and 4 = “true nearly all of the time”).12 A higher CD-RISC raw score equates to greater resilience.

Statistical analysis

Comparative analyses were conducted between the AKA and BKA groups. STATA (version 18.0; StataCorp LLC) was used to conduct paired t tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and univariate chi-square tests to then analyze normally distributed continuous data, nonnormally distributed continuous data, and categorical data, respectively. The Fisher exact test was used for cell contents less than 5. A P value less than .05 defined statistical significance. Regression analysis was performed to determine the effects of possible confounding variables identified in patient and surgical characteristic analysis. Variables that were identified as significant covariates from univariate regression analysis were used to create multivariable models.

Results

A total of 96 patients met inclusion criteria for the study, of which 22 (22.9%) underwent AKA and 74 (77.1%) underwent BKA. The median postoperative time points of survey completion were similar between patients in the AKA and BKA groups: 7.5 months (IQR, 32.5) and 10.8 months (IQR, 18.9), respectively (P = .845).

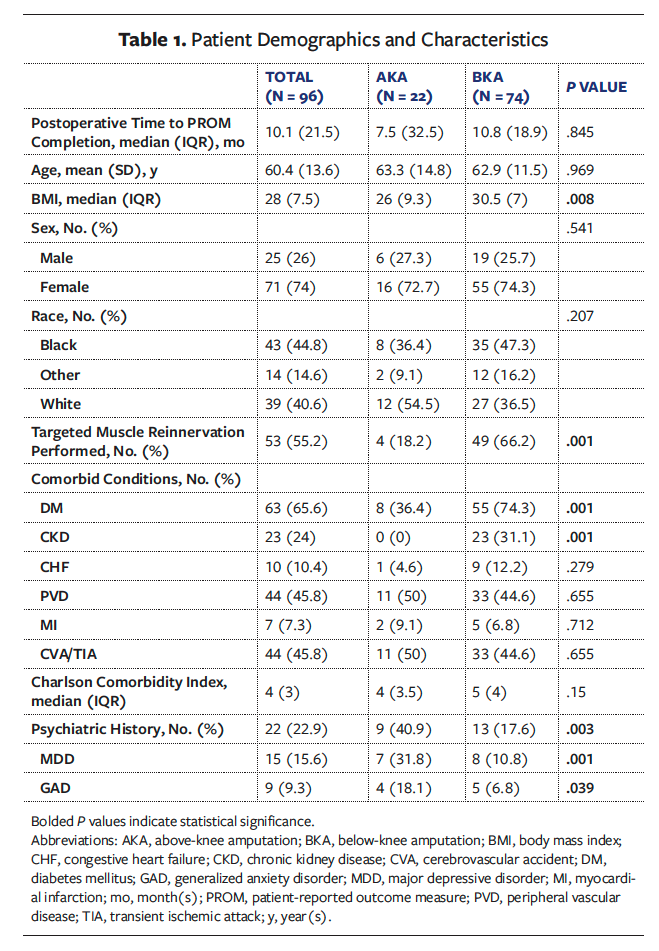

Table 1 displays patient characteristics. The average (SD) age of the total cohort was 60.4 (13.6) years, with no significant age difference between groups (P = .969). There were no significant differences in the distribution of sex (P = .541) or race (P = .207) between the 2 groups. The median BMI was significantly higher in the BKA group than in the AKA group (30.5 and 26.0, respectively; P = .008). The incidence of DM was significantly higher in the BKA group compared with the AKA group (74.3% and 36.4%, respectively; P = .001). Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was present exclusively in the BKA group (31.1% and 0%, respectively; P = .001). There were no significant differences between the groups for other evaluated comorbid conditions, including congestive heart failure (P = .279) and peripheral vascular disease (P = .655). Psychiatric history was significantly higher in AKA patients compared with BKA patients (major depressive disorder, 31.8% and 10.8%, respectively, P = .001; generalized anxiety disorder, 18.1% and 6.8%, respectively, P = .039). The CCI scores were not significantly different between the groups (P = .15), with the total cohort demonstrating a median score of 4 (IQR, 3), reflecting a 53% 10-year survival rate. Targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) was performed at a significantly higher rate in the BKA group compared with the AKA group (66.2% and 18.2%, respectively; P = .001).

Functional outcomes

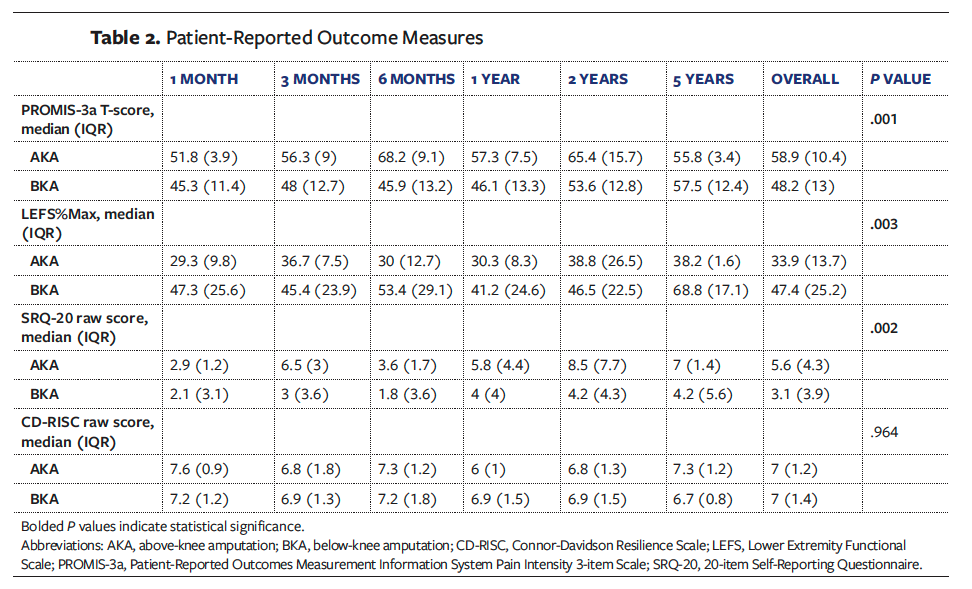

Postoperative PROMs are displayed in Table 2. Significant differences were observed between patients after AKA versus BKA in terms of mean overall function, as measured by the LEFS. Patients who underwent BKA reported a significantly higher overall median (IQR) LEFS score compared with those who underwent AKA (47.4 [25.2] and 33.9 [13.7], respectively; P = .003). Overall median (IQR) SRQ-20 scores were significantly lower in the BKA group compared with the AKA group (3.1 [3.9] and 5.6 [4.3], respectively; P = .002), reflecting lower psychological distress among patients who underwent BKA. There was no significant difference between groups in patients who scored 8 or above on the SRQ-20 scale (P = .351). As noted previously, scoring 8 or above signifies the need for further mental health evaluation. Pain intensity, as measured using the PROMIS-3a, was significantly lower in the BKA group compared with the AKA group (median [IQR], 48.2 [13] and 58.9 [10.4], respectively; P = .001). There was no significant difference in median (IQR) overall resilience (CD-RISC) scores between the BKA and AKA groups (7 [1.4] and 7 [1.2], respectively; P = .964).

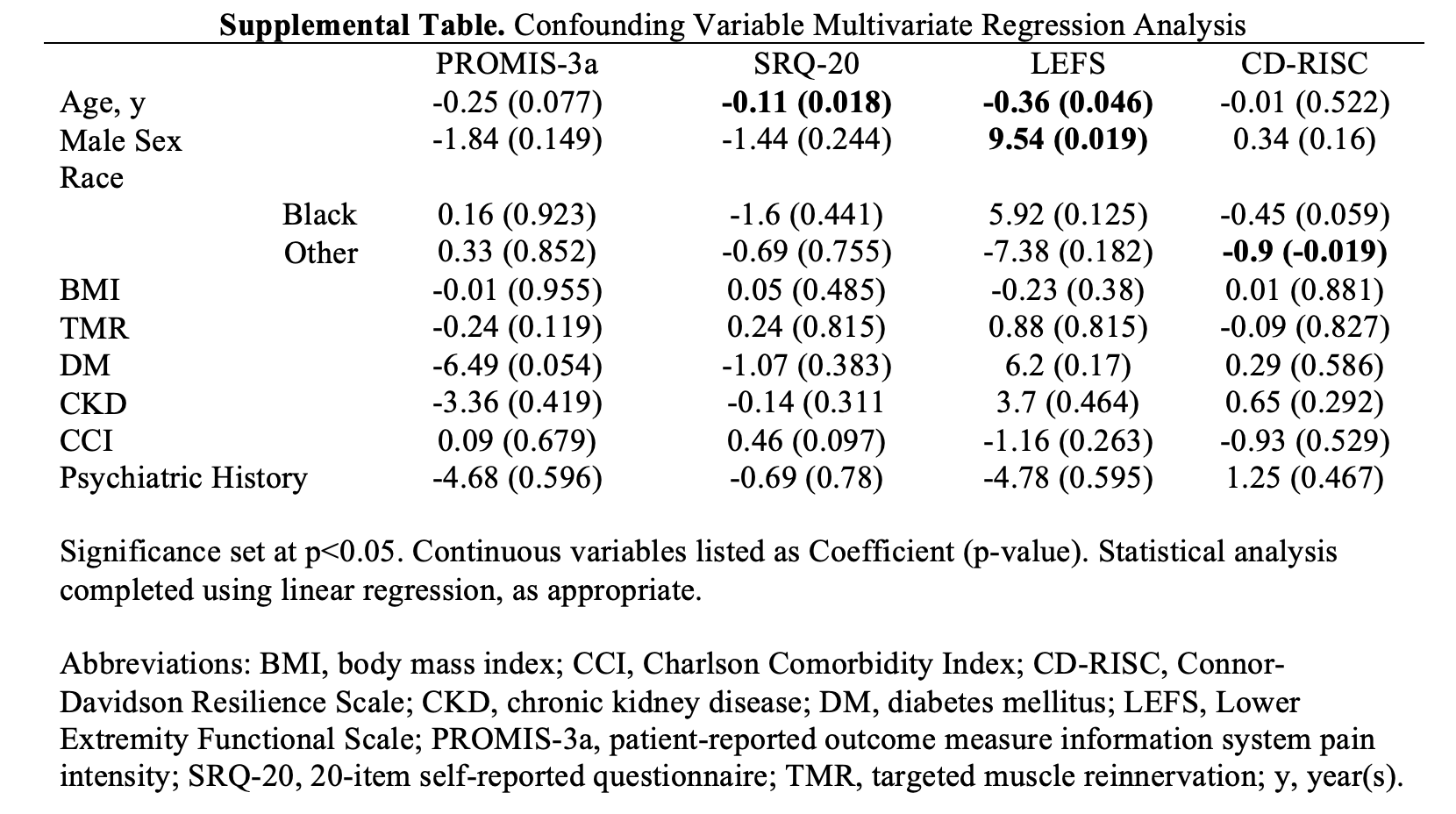

Results of multivariate regression analysis of patient characteristics are reported in the Supplemental Table. Older age was associated with lower psychological distress (SRQ-20, r = −0.11, P = .018) and lower function (LEFS, r = −0.36, P = .046). Male sex was a significant covariate for function (LEFS, odds ratio = 9.54, P = .019).

Discussion

This is the first study comparing postoperative PROMs between individuals with chronic nonhealing LE wounds who underwent nontraumatic AKA or BKA. In performing MLEA for nontraumatic LE wounds, the ideal end goal is a rapid return to baseline ambulatory function because of the importance of such function in extending lifespan in this population.13-15 However, BKA and AKA continue to be performed at a similar rate regardless of literature showing that AKA generally has higher morbidity and mortality compared with BKA.3,4 Patients suitable for a BKA ostensibly may receive an AKA instead due to ease of procedure or shorter surgical time, which is comparable to denying that patient potentially improved functional outcomes.

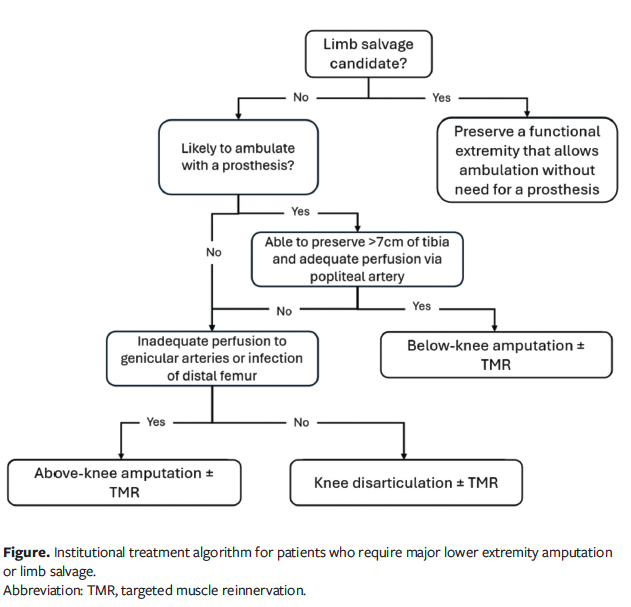

The present study shows that BKAs were performed at much higher rates than AKAs (77.1% and 22.9%, respectively) at the Center for Wound Healing because of its systematic approach to MLEA.13,14 The rates of BKA and AKA at the Center for Wound Healing are much higher than the nationwide rate; between 1993 and 2021, the ratio of BKA to AKA nationwide was 1.3:1.16 Nonambulatory patients are not treated with BKAs but instead preferably undergo knee disarticulation. This decision is partly due to the ease of performing TMR compared with AKA, because the sensory nerves required to make sensory-motor nerve anastomoses more closely match the isolated motor nerve size in knee disarticulation. The longer stump allows for better function in aiding trunk positioning and in sitting given the augmented ability to offload pressure and transfer with a longer stump. If there is insufficient blood flow to the knee, then AKA is performed. The authors’ institutional approach to MLEA decision-making is summarized in the Figure.

In the present study, patients who underwent BKA reported significantly higher postoperative functional capacity compared with those who underwent AKA across all time intervals. In BKA, preservation of the knee joint and restoration of the insertion of the gastrocnemius–soleus complex as well as the peroneal and anterior tibial muscles contributes to more efficient ambulation with a prosthesis and less energy expenditure.17,18 It also prevents the wasting of these muscles, thus prolonging the soft tissue padding over the tibia and fibula and diminishing the risk of soft tissue breakdown within the prosthesis. Without the knee joint present, AKA requires twice as much energy expenditure for ambulation compared with BKA and is not distal-end weight bearing.19 Prostheses for AKAs have more undesirable factors, such as increased weight, given the extra length required and the addition of a knee joint to the prosthesis construct. Furthermore, rehabilitation rates are higher with BKA compared with AKA, with approximately 65% to 91% of patients post-BKA ambulating with prostheses compared with less than 33% of patients doing so post-AKA after 6 months.20-22 At the institution where the present study was conducted, amputations are generally performed at or above the knee when the knee cannot be preserved due to wound location or significant lack of distal blood flow. If the patient is ambulatory at baseline, then every effort is taken to preserve the knee for eventual prosthesis fitting and use. All patients then undergo vigorous rehabilitation postoperatively to return as close to their baseline function as possible. The benefits of preserving the knee joint, increased postoperative function, and improved rehabilitation strongly validate that patients should undergo BKA whenever possible.

Although in the present study there were significantly lower levels of psychological distress in the BKA population compared with the AKA population, there was no significant difference in patients who scored 8 or above on the SRQ-20, which equates to no indication for mental health evaluation in this population. This finding coincides with existing literature that showed no significant difference in psychological distress between the 2 groups.23 However, patients undergoing any type of LE amputation are associated with higher rates of depression compared with the general population, as well as with higher rates of grief, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder.24 In the present study, there were more patients with prior psychiatric diagnosis (major depressive and generalized anxiety disorder) in the AKA group than in the BKA group, which may have influenced the observed between-group results. Psychological distress may ostensibly be greater in patients who had no ambulatory ability or who lost ambulatory ability, which occurs more in patients with AKA than in patients with BKA.25 Although, in the present study, regression analysis showed that prior psychiatric diagnosis was not a significant covariate regarding SRQ-20 scores, patients with AKA may be susceptible to other stressors that the SRQ-20 may not capture. Patients with AKA may have more pathology, such as advanced peripheral vascular disease, which may potentially affect psychological distress. Continued postoperative clinic visits for these patients may not only assess functional progress but may also provide a multidisciplinary environment in which mental health can be addressed and assessed in this vulnerable population. Moreover, addressing psychiatric diagnosis perioperatively in a multidisciplinary team setting may help improve psychological distress and overall functional outcomes.

Pain was markedly lower in the patients with BKA compared with those with AKA. AKA has shown a greater predisposition to the development of both neuropathic and residual pain.26 In addition to greater physical and mental relief, reduced postoperative stump pain may be associated with increased mechanical function or rehabilitation tolerance.27 If a patient experiences significant stump pain, they may not tolerate prosthesis use and thus would experience significant difficulty with ambulation and therefore not ambulate. Psychiatric disease has been shown to be independently associated with development of neuropathic pain after MLEA, whereas DM and elevated creatinine levels were associated with lower odds of developing neuropathic stump pain.26 However, in the current study, psychological diagnoses, DM, and CKD were not significant covariates in regard to pain scores (PROMIS-3a) after regression analysis despite higher rates of DM and CKD in patients with BKA and higher rates of prior psychiatric diagnosis in patients with AKA. The PROMIS-3a may not adequately assess neuropathic pain because the questions center around pain intensity rather than quality. Using a PROM that is validated for evaluating neuropathic pain may better expose the difference in postoperative neuropathic pain given the different patient characteristics between the BKA and AKA groups.

One method of pain reduction after MLEA is TMR, which has been shown to prevent symptomatic neuroma formation and reduce neuropathic pain after BKA and AKA.26,28 In the current study, BKA was associated with significantly higher rates of concurrent TMR. This is reflective of the institutional protocol since 2019 for TMR to be performed in all patients undergoing BKA. TMR is much more difficult in AKA because of the size discrepancy between the sciatic nerve and the branch of the motor nerve. There is also a need to flip the patient’s position to prone to perform the TMR in the posterior thigh; AKA is performed with the patient supine. The patient’s medical condition may preclude prone positioning or may necessitate a shorter operation, with traction neurectomies performed instead. However, regression analysis did not show TMR to be a significant covariate regarding PROMIS-3a scores. TMR may provide improved amputee postoperative pain, which may lead to better ambulation rates (91%) , as shown in a study of 100 BKAs with TMR by Chang et al.29

The ultimate decision of which type of MLEA to perform in nontraumatic patients with chronic wounds is made based on several patient- and physician-based factors. BKA requires adequate tibial length to function as a lever arm postamputation (7 cm to 20 cm from the joint line), to prevent contracture and minimize shear forces given the larger area of the amputation. The longer the tibia, the lower the shear pressure per centimeters squared and the better the moment arm, thus allowing for better function. Additionally, the longer the tibia the greater the chance to preserve the tibia in the event of surgical complications or a new distal ulceration.13 Preservation of the tibia avoids conversion to an AKA.

Adequate flow of the popliteal artery on preoperative angiography would help ensure perfusion of the BKA posterior flap and prevent complications, although the posterior flap has been shown to survive despite popliteal artery occlusion.30 A patient who is ambulatory at baseline may be more likely to undergo BKA due to ease of prosthesis use and more rapid return of function. Conversely, proximal wounds or extensive severe infections that require prohibitive margins of resection may require AKA. Severe vascular compromise of the extremity may also lead to AKA, such as an occluded popliteal artery without significant collateral flow to the lower leg. AKA may also be perceived to be a simpler procedure because there is no need to assess tibial, fibular, and flap length, and the surgical time is shorter. Given the better functional outcome with BKA, shorter surgical time and simpler surgery never justifies performing an AKA in a patient who is eligible for BKA. A functional BKA almost doubles the published 5-year survival rate in individuals with DM, and that is because they can ambulate.4 If an AKA must be performed, myodesis of the muscle groups (quadriceps, adductors, hamstrings) may help preserve strength in the thigh and prevent muscle wasting, thus assisting in wound healing and rehabilitation potential.31,32 Although the institution of the authors of the present study consistently performs myodesis, others may not take extra time to perform the muscle stabilization, which may ultimately affect patient function and prosthesis use. The findings of the present study that patients with AKA have greater postoperative pain and less function compared with patients with BKA suggest that the appropriate procedure was performed on the appropriate patient.

Through-knee amputation (TKA), or knee disarticulation, promotes ease of transfer, promotes preservation of the adductor muscle insertion, enhances energy conservation, and provides a distal-end weight bearing stump in patients who are nonambulatory at baseline.33 However, this technique is not commonly performed, and performing the surgery may be dependent on surgeon experience with the procedure. Additionally, an available prosthetist who is comfortable and familiar with making a TKA prosthesis is required. Generally, TKAs are performed in patients who cannot walk or who are unable to have an amputation shorter than a residual 7 cm tibia. It also requires a noninfected distal femur and adequate perfusion of the soft tissues of the proximal leg.14 Such requirements result in far fewer TKAs being performed than BKAs or AKAs. TKAs aim to maximize residual limb length, which, in comparison to AKAs, may be the difference in patients’ ability to perform acts of daily living, including transferring to wheelchairs or out of bed. Future studies incorporating PROMs in a comparative analysis of TKA, BKA, and AKA could provide additional detail about postoperative rehabilitation of patients in each group.

If a BKA does not heal or develops infection, stump revision may be required, depending on the extent of infection or wound. Given the functional and mortality benefits favoring BKA, it is imperative to preserve or salvage the BKA if possible. Depending on the institution, specialists in vascular surgery or interventional radiology may perform endovascular interventions to revascularize the BKA. If the vasculature is not amenable to endovascular intervention, a vascular surgeon may perform a bypass, such as femoral–femoral or femoral–popliteal (depending on the level of stenosis or occlusion), to aid wound healing. If the patient does not have concerns for vascular insufficiency and the wound extent does not necessitate BKA revision, then a wound care team, if available, can assist with negative pressure wound therapy or advanced dressings to aid in wound healing.35 If a stump revision is required, the residual tibial stump may be reduced to as little as 7 cm from the knee to accommodate for further myocutaneous debridement and creation of a new healthy posterior flap. Given the shorter tibial length, the patient must undergo intense physical rehabilitation to prevent contracture and maintain functionality of the BKA. If there is severe vascular compromise that is not amenable to revascularization, if the extent of wound and infection prevent creation of a healthy posterior flap or tibial length greater than or equal to 7 cm, or if there is continued debilitating pain despite TMR and/or optimal multimodal pain regimen, then a TKA can be performed to preserve limb length. AKA can be performed if no surgeon is available to perform TKA, or if the patient is not amenable to a TKA.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional retrospective design precludes the ability to establish causality. Furthermore, the reliance on patient-reported outcomes introduces the potential for response bias. Additionally, the smaller sample size in the AKA group may limit the generalizability of the findings. As part of the inclusion criteria, some participants filled out only 1 survey set, and thus their function, pain intensity, and psychological distress or resilience were not tracked over time. The lack of preamputation PROMs makes it difficult to compare changes in pre- and postamputation function or to determine whether patients had preexisting depressive symptoms. Moreover, the patients with BKA and AKA were not evenly matched for preoperative functional, physical, or mental status, extent of tissue necrosis, or extent of arterial disease. Future research with larger, prospective cohorts and pre- and postoperative objective functional assessments would help to validate and expand upon these results.

Conclusion

This is the first study to compare BKA and AKA postoperative PROMs in patients with nontraumatic, chronic nonhealing wounds. Patients with BKA have significantly higher function scores and lower pain scores compared with patients with AKA. These outcomes highlight the benefits of preserving the knee joint when possible. The relative heterogeneity of PROMs across groups may reflect that the decision for level of amputation was appropriately made for the intended patients.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Ryan P. Lin, MD1; Danny S. Chamaa, BS2; Sami Ferdousian, MS1; Rachel N. Rohrich, BS1; Isabel A. Snee, BS2; Richard C. Youn, MD1; Karen K. Evans, MD1; and Christopher E. Attinger, MD1

Affiliations: 1Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, USA; 2Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Disclosures: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: This study received institutional review board exemption Study 00004145.

Correspondence: Ryan P. Lin, MD; MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, 3800 Reservoir Road, NW, Washington, DC 20007; Ryan.Lin@medstar.net

Manuscript Accepted: October 21, 2025

References

1. Moxey PW, Gogalniceanu P, Hinchliffe RJ, et al. Lower extremity amputations--a review of global variability in incidence. Diabet Med. 2011;28(10):1144-1153. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03279.x

2. Fan KL, DeLia D, Black CK, et al. Who, what, where: demographics, severity of presentation, and location of treatment drive delivery of diabetic limb reconstructive services within the National Inpatient Sample. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(6):1516-1527. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006843

3. Harding JL, Andes LJ, Rolka DB, et al. National and state-level trends in nontraumatic lower-extremity amputation among U.S. Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes, 2000-2017. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(10):2453-2459. doi:10.2337/dc20-0586

4. Zolper EG, Deldar R, Haffner ZK, et al. Effect of function-based approach to nontraumatic major lower extremity amputation on 5-year mortality. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;235(3):438-446. doi:10.1097/XCS.0000000000000247

5. Churruca K, Pomare C, Ellis LA, et al. Patient-

reported outcome measures (PROMs): a review of generic and condition-specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expect. 2021;24(4):1015-1024. doi:10.1111/hex.13254

6. Kosinski M, Nelson LM, Stanford RH, Flom JD, Schatz M. Patient-reported outcome measure development and validation: a primer for clinicians. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12(10):2554-2561. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2024.08.030

7. Bull C, Teede H, Watson D, Callander EJ. Selecting and implementing patient-reported outcome and experience measures to assess health system performance. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(4):e220326. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0326

8. Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, Patierno C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: a critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91(1):8-35. doi:10.1159/000521288

9. Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179-1194. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011

10. Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. Phys Ther. 1999;79(4):371-383.

11. Beusenberg M, Orley JH, World Health Organization. A user‘s guide to the Self Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2174412

12. Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76-82. doi:10.1002/da.10113

13. Brown BJ, Attinger CE. The below-knee amputation: to amputate or palliate? Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013;2(1):30-35. doi:10.1089/wound.2011.0317

14. Brown BJ, Crone CG, Attinger CE. Amputation in the diabetic to maximize function. Semin Vasc Surg. 2012;25(2):115-121. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2012.04.003

15. Molina CS, Faulk J. Lower Extremity Amputation. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

16. Kougias P, Sharath SE, Ferguson C, et al. Turning tides: evolving comorbidity profiles, demographic shift, and the unexpected rise of major lower extremity amputations. Ann Surg. 2025;282(3):429-438. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000006813

17. Agarwal A, Morton RL. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to guide clinical care: recommendations and challenges. Med J Aust. 2022;217(2):111. doi:10.5694/mja2.51625

18. Ihmels WD, Miller RH, Esposito ER. Residual limb strength and functional performance measures in individuals with unilateral transtibial amputation. Gait Posture. 2022;97:159-164. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.07.257

19. Jones DW, Farber A. Review of the Global Vascular Guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(2):161-162. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4928

20. McGinnis A, Weber Z, Zuhaili B, Garrett HE Jr. Mobility rates after lower-limb amputation for patients treated with physician-led collaborative care model. Ann Vasc Surg. 2024;105:99-105. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2024.02.010

21. MacCallum KP, Yau P, Phair J, Lipsitz EC, Scher LA, Garg K. Ambulatory status following major lower extremity amputation. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;71:331-337. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2020.07.038

22. O’Meara R, Chawla K, Gorantla A, et al. The impact of sociodemographic variables on functional recovery following lower extremity amputation. Ann Vasc Surg. 2025;110(Pt B):317-336. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2024.07.095

23. Abdel Rahim A, Tam A, Holmes M, Mittapalli D. The effect of amputation level on patient mental and psychological health, prospective observational cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;84:104864. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104864

24. Jo SH, Kang SH, Seo WS, Koo BH, Kim HG, Yun SH. Psychiatric understanding and treatment of patients with amputations. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2021;38(3):194-201. doi:10.12701/yujm.2021.00990

25. Daso G, Chen AJ, Yeh S, et al. Lower extremity amputations among veterans: have ambulatory outcomes and survival improved? Ann Vasc Surg. 2022;87:311-320. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2022.06.007

26. Lans J, Groot OQ, Hazewinkel MHJ, et al. Factors related to neuropathic pain following lower extremity amputation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150(2):446-455. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000009334

27. Leal NTB, de Araujo NM, de Oliveira Silva S, et al. Pain management in the postoperative period of amputation surgeries: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(21-22):7718-7729. doi:10.1111/jocn.16846

28. Boctor MJ, Klosowiak JL, Moradian S, Taritsa I, Dumanian GA, Ko JH. Targeted muscle reinnervation in above knee amputation: surgical technique. Neurosurg Focus Video. 2023;8(1):V12. doi:10.3171/2022.10.FOCVID2293

29. Chang BL, Mondshine J, Attinger CE, Kleiber GM. Targeted muscle reinnervation improves pain and ambulation outcomes in highly comorbid amputees. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(2):376-386. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000008153

30. Alfawaz A, Kotha VS, Nigam M, et al. Popliteal artery patency is an indicator of ambulation and healing after below-knee amputation in vasculopaths. Vascular. 2022;30(4):708-714. doi:10.1177/17085381211026498

31. Fabre I, Thompson D, Gwilym B, et al. Surgical techniques of, and outcomes after, distal muscle stabilization in transfemoral amputation: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2024;98:182-193. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2023.07.105

32. Ranz EC, Wilken JM, Gajewski DA, Neptune RR. The influence of limb alignment and transfemoral amputation technique on muscle capacity during gait. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2017;20(11):1167-1174. doi:10.1080/10255842.2017.1340461

33. Parry JA, Neufeld E. Knee disarticultion versus transfemoral amputation: the prosthetist’s perspective. J Orthop Trauma. 2022;36(9):e358-e361. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000002364

34. Balan N, Qi X, Keeley J, Neville A. A novel strategy to manage below-knee-amputation (BKA) stump complications for early wound healing and BKA salvage. Am Surg. 2023;89(10):4055-4060. doi:10.1177/00031348231175504