Effect of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy with Instillation and Dwell Time on Health Care Utilization and Costs in South Africa

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d) provides repeated wound cleansing plus the therapeutic benefits of traditional NPWT and has been elevated to a first-line therapy in some regions given evidence of its effectiveness. Objective. To examine the effect of NPWTi-d on health care utilization and costs in South Africa, where NPWTi-d may still be used as a therapy of last resort. Methods. This retrospective study was conducted utilizing a large, South African, private health insurance claims database. A matched cohort of 836 inpatients receiving NPWTi-d or NPWT for various wound types from 2018 through 2022 was created using propensity scoring. Differences in outcomes were compared between groups using t tests. Results. Despite matching, patients who received NPWTi-d were likely more complex than those who received NPWT, as indicated by a longer length of stay (18.5 days and 13.2 days, respectively; P < .001) and higher overall care costs during the index hospital admission. Readmission rates were similar between groups; however, patients who received NPWTi-d were less likely to have visits for wound-related subacute care or rehabilitation (20.1% vs 53.6%). The average cost of this care (in South African rand) was significantly lower for patients receiving NPWTi-d than for those receiving NPWT (R3 231 and R12 317, respectively; P < .001). Conclusion. Although this study had limitations, including a potential selection bias, study data suggest that NPWTi-d may reduce wound-related health care utilization and costs for some patients through decreases in visits for subacute care. More studies are needed to fully assess how NPWTi-d affects wound care pathways, patient outcomes, and costs in South Africa.

Introduction

Wound treatment is particularly challenging in developing nations such as South Africa, where rates of inequality and poverty are high,1 wound care standards are lacking,2 circulatory diseases and diabetes are prevalent,3 injuries are a leading cause of years of healthy life lost,4 and access to health care is often limited.¹ Advanced wound healing technologies may reduce the need for frequent visits with clinicians and use of other wound products, thus reducing health care utilization and costs.5

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) was introduced in the early 1990s.6 It can promote wound healing by utilizing negative pressure to remove exudate and infectious materials from wounds, draw wound edges together, and promote the formation of granulation tissue.7-9 The benefits of NPWT, including earlier wound closure and reductions in operating room (OR) visits and hospital length of stay (LOS), have been demonstrated in various studies, and the therapy is now commonly used in the management of both acute and chronic wounds.5,10,11

Unlike NPWT, which applies negative pressure to wounds in a sealed moist environment, NPWT with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d) allows for wound cleansing through the introduction of a topical wound solution over the wound bed with a set interval of dwell time followed by removal using alternating cycles of negative pressure while the dressing remains in place.12,13 When used with reticulated open cell foam with 1-cm holes (ROCF-CC), NPWTi-d can provide hydromechanical removal of infectious materials, nonviable tissue, and wound debris through the dressing’s mechanical action in conjunction with the process of instilling and allowing topical solutions to soak in the wound bed for ≤30 minutes during the instillation phase.12 Thus, NPWTi-d with ROCF-CC can be a bedside alternative to surgical debridement.12 A growing number of studies, mainly from the United States, have reported lower bacterial bioburden levels, fewer surgical debridements, improved odds of and reduced time to wound closure, and reduced length of therapy (LOT) for patients treated with NPWTi-d versus NPWT alone for various complex wound types.13-16

Although NPWTi-d has gained traction and has been elevated to a first-line therapy in some regions,13,17 its use has been limited in some geographic areas, where it remains a last-resort therapy. In guidelines published in 2022, an international consensus panel recommended use of NPWTi-d as an adjunctive therapy along with debridement and antibiotics for a wide variety of wound types and conditions that could potentially benefit from daily periodic wound cleansing while the dressing remains in place.17 However, the 2021 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines stated that although NPWTi-d shows promise for the treatment of acute infected or chronic wounds that are not healing, there is not enough high-quality evidence to support the case for routine adoption.18 In recently published recommendations based on international research, clinical expertise, and European guidelines, the Wound Healing Association of South Africa (WHASA) affirmed that NPWT reduces tissue edema, increases formation of granulation tissue, increases perfusion, and can reduce wound contamination when used in conjunction with NPWTi-d.5 The WHASA recommended the use of NPWT for a variety of nonhealing wounds, including open fractures, traumatic or surgical wounds, dehisced abdominal and sternal wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, wounds requiring skin grafting, and acute burns, but did not provide guidance for the use of NPWTi-d.5

The lack of large-scale prospective studies examining NPWTi-d, particularly outside the United States where NPWTi-d may be used differently, has been cited by the National Health Service and South African insurers as a barrier to widespread use of NPWTi-d.18 The dearth of data demonstrating whether the initial costs associated with NPWTi-d use can decrease costs of wound therapy in the long term also has limited uptake of NPWTi-d, and it is only authorized by some payers as an adjunctive first-line therapy for infected wounds. To the knowledge of the authors of the current study, no studies have been conducted in the region examining outcomes for patients receiving NPWTi-d. This study sought to address this gap in the literature by examining the effect of NPWTi-d on health care utilization and costs in South Africa.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective, matched cohort analysis was conducted utilizing a large, South African, private health insurance claims database. The study used de-identified data and was exempt from institutional review board review.

Study population

Patients who received NPWTi-d (3M Veraflo Therapy; Solventum Corporation) and NPWT (3M V.A.C. Therapy, Solventum Corporation) during a hospital admission from 2018 to 2022, as indicated by National Pharmaceutical Product Index codes in the billing data, were eligible for study inclusion. Patients with claims for both NPWT and NPWTi-d in the same visit were assigned to the NPWTi-d cohort. Patients with a greater than 5-day lag between use of the 2 products were excluded.

Measures

Patient demographics—including age, sex, and province, as well as payer, admission type, and hospital setting—were extracted from the database. The number of patient comorbidities was calculated based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10)19 codes that were documented for the index admission and/or during the year prior to the index admission if the cost for the ICD-10 code exceeded R1000. Wound types were determined using ICD-10 and/or diagnosis related group (DRG) codes. Wound disruption or infection was determined using ICD-10 diagnosis codes. Health care utilization outcomes were collected for the index hospitalization where NPWTi-d or NPWT was first utilized, and for wound-related readmissions, subacute care, and rehabilitation visits during the LOT as well as in the 60 days following discharge. LOT was calculated as the number of days between the admit date of the initial event and the last wound dressing claim occurring before a gap of greater than 14 days between wound dressing claims. Metrics included LOS, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and number of visits to the OR. Readmissions, subacute care, and rehabilitation visits were determined to be wound-related if the DRG or ICD-10 code was wound-related and/or the patient had a claim for NPWTi-d or NPWT.

Costs in South African rand were extracted from billing data. The cost of the index hospitalization was calculated as the total cost of care, including NPWTi-d and NPWT devices and wound care products. Wound-related hospital readmission costs were calculated as the total cost of hospitalizations occurring within a patient’s LOT during the 60 days following discharge. Costs for wound-related subacute care and rehabilitation visits were calculated as the total costs of these visits occurring within a patient’s LOT during the 60 days following discharge. The average overall treatment cost was the sum of the total costs of the index hospitalization and any wound-related hospital readmissions or subacute care or rehabilitation visits occurring during the LOT. Reported wound care costs only included NPWTi-d or NPWT product costs and were calculated for the index hospitalization and wound-related readmissions and subacute care or rehabilitation visits occurring during the LOT. Daily cost of NPWTi-d or NPWT use was calculated as the total product cost divided by the LOT.

Statistical analysis

A total of 465 patients received NPWTi-d, and 2541 patients received NPWT during the study time frame and met the study inclusion criteria. Propensity score matching was used to simulate conditions of a randomized controlled trial by creating a matched sample in which the distribution of observed covariates was similar between treated and control groups. After the removal of outlier patients with index hospitalization, readmissions, subacute care, or rehabilitation costs beyond the upper interquartile range, propensity scoring was conducted using the PsmPy library in Python20 to match the remaining 418 patients in the NPWTi-d cohort with a similar group of 418 patients who received NPWT using the nearest neighbor matching technique. Propensity scores for each patient were modeled using logistic regression with gender, age, insurance plan, total comorbidities, wound type, the presence of infection or wound disruption, admission type (emergency or elective), and the hospital network included as covariates in the model. After propensity score matching, the standardized mean difference between cohorts for all covariates included in the model was less than 0.15, with a difference of less than 0.10 for the majority, indicating that the matching was effective at reducing variability between the NPWTi-d and NPWT cohorts on observed covariates. Differences in outcomes between groups were compared using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Results

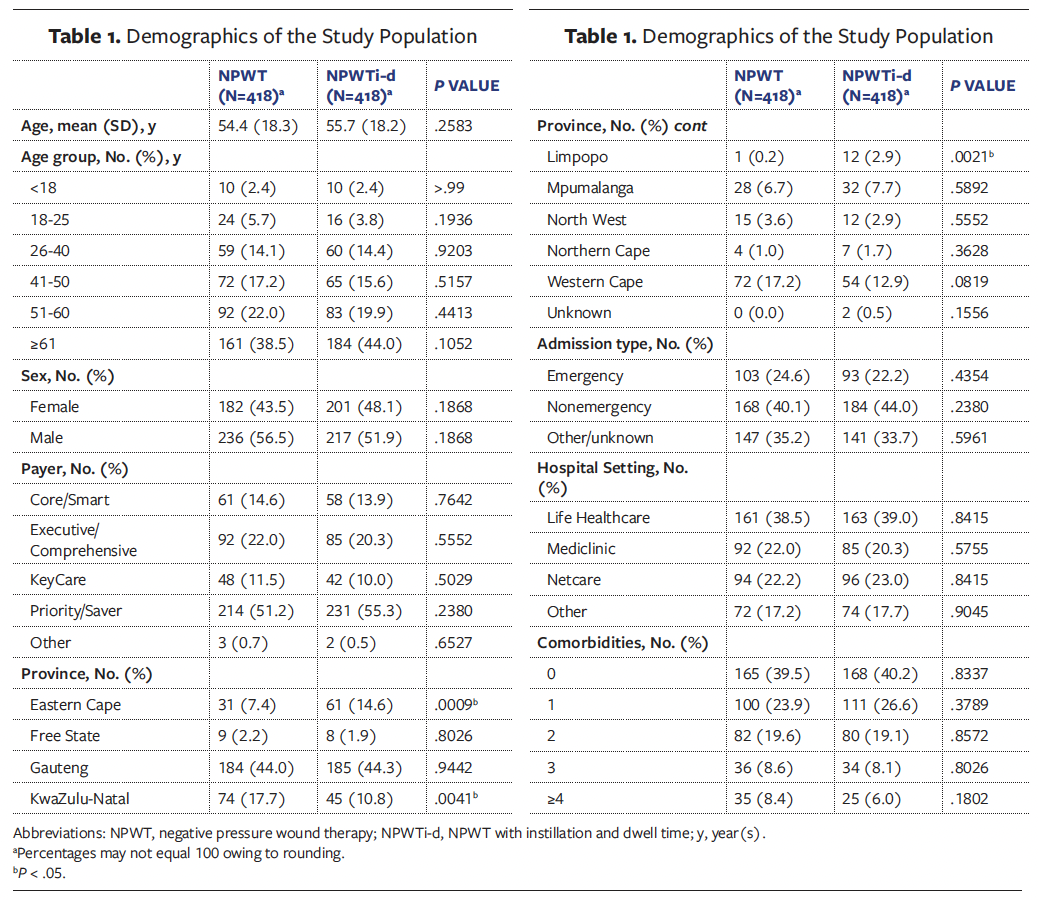

After matching, the NPWTi-d and NPWT cohorts were similar in terms of demographics, except for the province where treatment occurred (Table 1). Over 60% of included patients were aged 51 years or older, and 38.5% of patients who received NPWT and 44% of patients who received NPWTi-d were aged 61 years or older. Most patients in both cohorts had a priority/saver plan. Approximately 44% of patients in both groups received treatment in Gauteng province. A significantly higher percentage of patients in Eastern Cape and Limpopo provinces received treatment with NPWTi-d, while use of NPWT was significantly higher in KwaZulu-Natal province. The percentage of emergency admissions was slightly higher for patients who received NPWT (24.6%) compared with those who received NPWTi-d (22.2%); this difference was not significant. Most patients in both groups had 0 or 1 documented comorbidities.

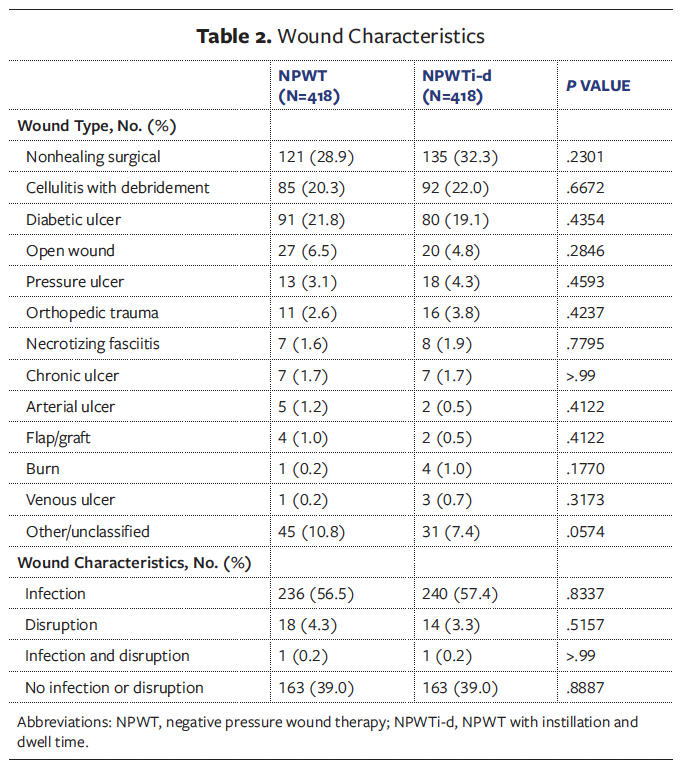

There were no significant differences in wound types between groups (Table 2). The most common wound types for patients receiving NPWT and NPWTi-d, respectively, were nonhealing surgical wounds (28.9% and 32.3%), cellulitis with debridement (20.3% and 22.0%), and diabetic ulcers (21.8% and 19.1%). In both groups, approximately 57% of patients had infected wounds.

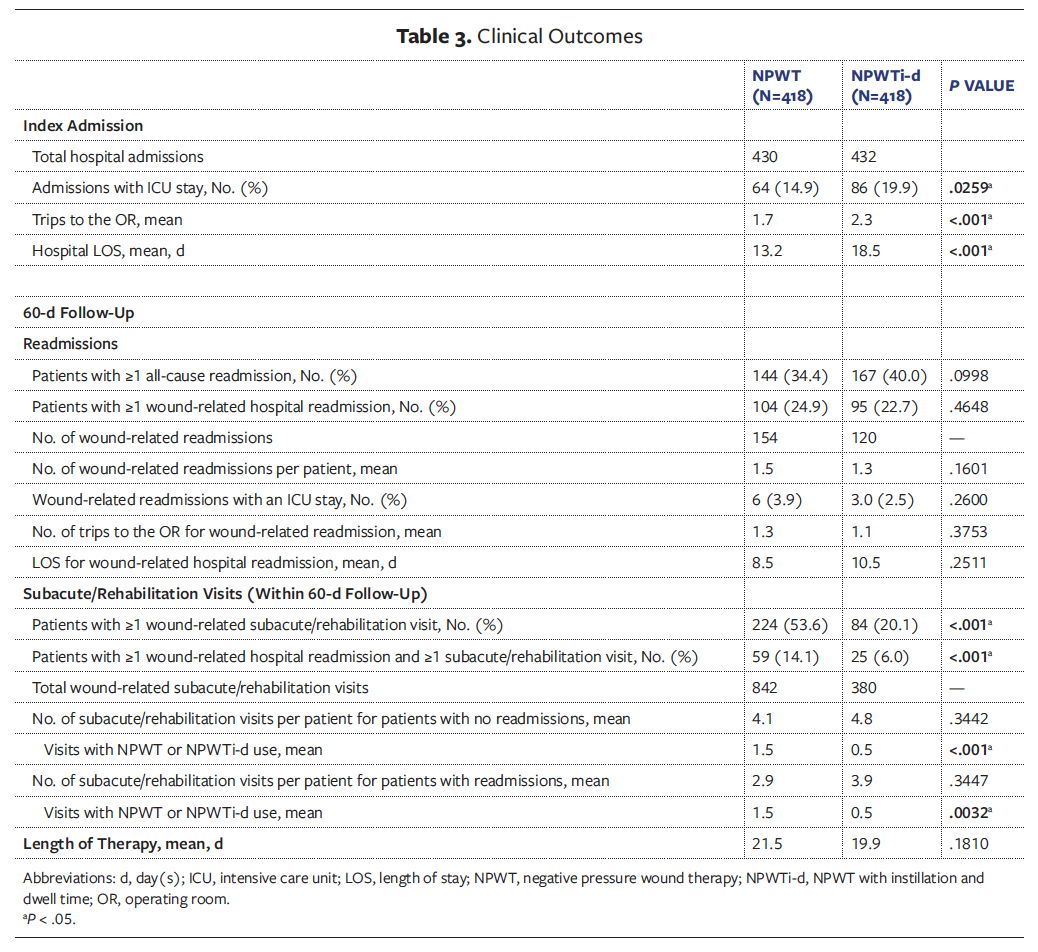

Clinical outcomes are displayed in Table 3. There were a total of 430 and 432 index admissions for unique wounds in the NPWT and NPWTi-d groups, respectively. A significantly higher percentage of admissions for NPWTi-d patients included a stay in the ICU compared with admissions for the NPWT group (19.9% and 14.9%, respectively; P = .0259). The average number of trips to the OR was also significantly higher for patients receiving NPWTi-d than for those receiving NPWT (2.3 and 1.7, respectively; P < .001). Patients receiving NPWTi-d also had a significantly longer mean LOS compared with patients receiving NPWT (18.5 days and 13.2 days, respectively; P < .001).

A higher percentage of patients who received NPWTi-d had at least 1 all-cause readmission in the 60 days following the index wound admission compared with patients who received NPWT (40.0% and 34.4%, respectively; P = .0998). However, fewer patients who received NPWTi-d had a wound-related readmission (22.7% and 24.9%, respectively; P = .4648), and the mean number of wound-related readmissions per patient was slightly lower for these patients compared with patients who received NPWT(1.3 and 1.5, respectively; P = .1601). Patients who received NPWT had more trips to the OR during readmission compared with patients who received NPWTi-d (mean: 1.3 and 1.1, respectively; P = .3753). Readmission mean LOS was higher for patients who received NPWTi-d compared with NPWT (10.5 days and 8.5 days, respectively; P = .2511); however, these differences were not statistically significant.

Patients who received NPWTi-d were significantly less likely than those who received NPWT to have 1 or more wound-related subacute care or rehabilitation visits in the 60 days following the index wound admission (20.1% and 53.6%, respectively; P < .001). Additionally, the percentage of patients who received NPWTi-d who had 1 or more hospital readmission and 1 or more subacute care or rehabilitation visit was lower than the percentage of patients who received NPWT (6% and 14.1%, respectively; P < .001). The total number of subacute care/rehabilitation visits was lower for patients who received NPWTi-d than for patients who received NPWT (380 and 842, respectively). The average number of visits with NPWT or NPWTi-d product use for patients with and without readmissions also was lower for patients who received NPWT (0.5 and 1.5, respectively, for each comparison; P < .001). The average LOT was shorter for patients who received NPWTi-d than for patients who received NPWT (21.5 days and 19.9 days, respectively; P = .1810); this difference was not statistically significant.

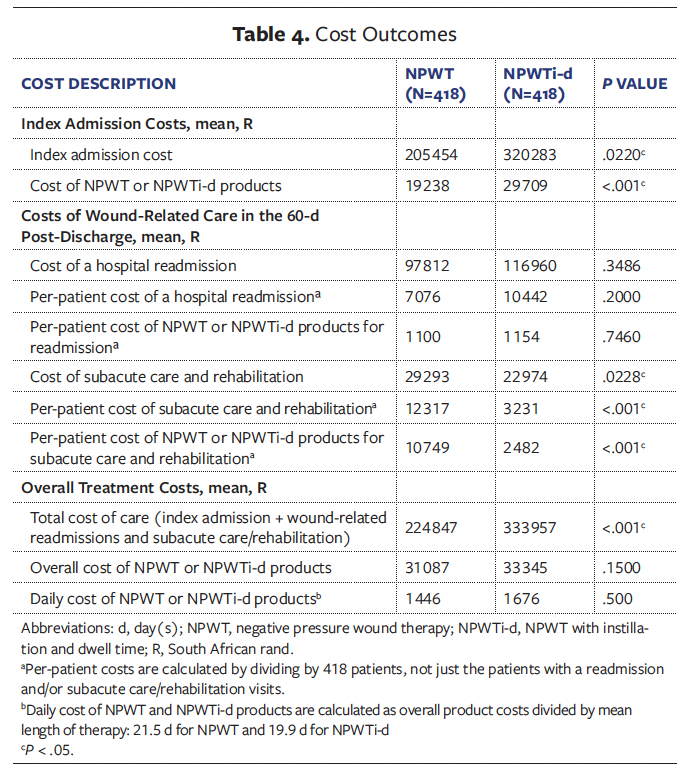

Cost outcomes are displayed in Table 4. The mean total cost of the index admission was significantly higher for patients who received NPWTi-d than for patients who received NPWT (R320 283 and R205 454, respectively; P = .0220), including the cost of NPWTi-d or NPWT products (R29 709 and R19 238, respectively; P < .001). The mean cost of a hospital readmission was higher for patients who received NPWTi-d than for patients who received NPWT, but the difference was not statistically significant (R116 960 vs R97 812, respectively; P = .3486). When averaged across all 418 patients in each cohort and not just patients who had a readmission, the per-patient cost of a readmission was not significantly different for patients who received NPWTi-d vs NPWT (R10 442 and R7 076, respectively; P = .2000), including the cost of NPWTi-d and NPWT products (R1 154 and R1 100, respectively). However, the average cost of subacute care and rehabilitation utilization (R22 974 and R29 293, respectively; P = .0228) as well as the per-patient cost of these visits (R3 231 and R12 317, respectively; P < .001), including per-patient cost of NPWTi-d and NPWT products (R2 482 and R10 749, respectively; P < .001), were significantly lower for patients who received NPWTi-d compared with those who received NPWT.

The overall cost of treatment, including the index hospitalization and wound-

related readmissions and subacute care/rehabilitation visits occurring within 60 days of hospital discharge, was higher for patients receiving NPWTi-d than for patients receiving NPWT (R333 957 and R224 847, respectively; P < .001). The mean overall cost of NPWTi-d and NPWT products (R33 345 and R31 087, respectively; P = .1500) and the average daily cost (R1 676 and R1 446, respectively; P = 0.5000) were slightly higher for NPWTi-d patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Although patients in this study who received NPWTi-d had a longer LOS and higher overall treatment costs during the index hospitalization compared with patients who received NPWT, the study data suggest that NPWTi-d may reduce wound-related health care utilization and costs in the long term through decreases in wound-related subacute care and rehabilitation visits. Nearly 54% of patients who received NPWT had 1 or more subacute care or rehabilitation visits, compared with 20% of patients who received NPWTi-d. When averaged across all the patients included in the study, the average cost of subacute care and rehabilitation for patients with these visits, including product costs, was significantly lower for those who received NPWTi-d than for those who received NPWT. Although patients who received NPWTi-d had a longer mean initial hospital LOS, there was no significant difference in average LOT between groups when accounting for follow-up visits.

Some studies have found the use of NPWTi-d to be associated with reduced index LOS14,15 and costs14 compared with NPWT, while others have found no significant differences in LOS between treatment arms.13,21 In a study comparing outcomes of patients who received NPWTi-d versus NPWT for the treatment of extremity and trunk wounds, Gabriel et al14 found that use of NPWTi-d was associated with reductions in mean LOS (8.1 days vs 27.4 days, respectively), time to wound closure (4.1 days vs 20.9 days, respectively), and OR debridements (2.0 vs 4.4, respectively). In the economic model, use of NPWTi-d showed a potential average reduction of $8143 per patient for OR debridements and $1418 in therapy costs compared with NPWT despite the higher cost of NPWTi-d because the LOT was significantly shorter with NPWTi-d.

In the current study, patients who received NPWTi-d had a significantly longer hospital LOS and significantly higher total cost of care. The higher treatment costs during the initial hospitalization were partly due to the higher cost of the NPWTi-d products compared with NPWT products (R29 709 and R19 238, respectively). The insurer of the patients included in this study absorbed these product costs because it reimbursed hospitals for the costs of NPWTi-d as a first-line treatment provided patients had a positive result on microscopy, culture, and sensitivity (MCS) analysis indicating the presence of infection and had been prescribed antibiotics. The authors of the present study were unable to discern whether the other costs were related to use of either NPWTi-d or NPWT, or other differences between the groups in underlying patient or wound characteristics or treatment received in addition to wound care. For instance, some patients may have been admitted with multiple traumatic injuries, head injuries, or need for ventilation that would require advanced care in addition to wound treatment. In this study, more patients with NPWTi-d had an ICU stay. Some wounds may have also been more complex due to factors such as size, depth, location, and presence of infection, but information on most of these factors was not documented in the claims data used for the study. Hospital LOS also may have been confounded by factors such as hospital discharge procedures and the availability of community care.18 Thus, hospital LOS and associated costs may not be the best outcome measures for wound care because they typically do not account for health care utilization throughout the entire wound healing process.18

Although the authors of the current study attempted to control for potential differences between patients who received NPWTi-d and those who received NPWT through propensity score matching, the authors could only match on elements that were available in data. The presence of infection as indicated by ICD-10 diagnoses codes was included in the model, and 57% of patients in both treatment groups had an infected wound based on documented codes. However, as previously mentioned, the insurer’s funding protocol for the patients included in this study indicated that NPWTi-d is only funded as a first-line treatment for patients with an infection indicated by a positive result on MCS analysis and an antibiotics prescription. Thus, it is probable that some infections were not documented using ICD-10 codes, and patients who received NPWTi-d may have been more likely than patients who received NPWT to have an infected wound that was more complex, given the reimbursement criteria and that NPWTi-d is frequently still used as a therapy of last resort by some clinicians and in some geographic areas.

The timing of the application of NPWTi-d can also influence patient outcomes. In a recent study, early initiation of NPWTi-d was associated with better outcomes compared with late initiation, including reductions in number of debridements, length of time to final procedure, hospital LOS, and cost of the index admission.22 Unfortunately, the data for the current study did not include timestamps indicating when NPWT or NPWTi-d was initiated during the index admission. If NPWTi-d was used frequently as a therapy of last resort and was applied several days after the patient was admitted, then the observed differences in inpatient LOS and costs for patients receiving NPWTi-d vs NPWT may be due to the delay in NPWTi-d application rather than the effectiveness of the device.

Despite the indications that patients who received NPWTi-d were more complex than those who received NPWT, patients who received NPWTi-d were significantly less likely to have a wound-related subacute care or rehabilitation visit in the 60 days following the index wound admission. Perhaps patients who received NPWTi-d were more likely to achieve wound closure at discharge compared with patients who received NPWT (in line with previous research15,23), thus eliminating the need for further visits for wound care. In a meta-analysis examining use of NPWTi-d vs NPWT or standard of care in orthoplastic surgery, De Pellegrin et al23 found that patients treated with NPWTi-d were 2 times as likely to achieve wound closure. Use of NPWTi-d was also associated with a significant reduction in the rate of complications, which is directly correlated with risks for patient and treatment costs.23 In a multisite randomized trial of wounds requiring surgical debridement, Kim et al24 observed a similar time to wound closure for patients who received NPWT vs NPWTi-d; however, patients who received NPWT were over 3 times more likely to be readmitted. In the current study, patients who received NPWTi-d may also have had fewer complications, which may have contributed to the observed reduction in wound-related subacute care or rehabilitation visits.

Although the NPWTi-d product costs were slightly higher compared with the cost of NPWT, the insurer may have achieved cost savings through a reduction in wound-related subacute care and rehabilitation visits following hospitalization. The average cost of wound-related subacute care and rehabilitation for patients who received this care was significantly lower for patients treated with NPWTi-d (R22 974) than for patients treated with NPWT (R29 293). When averaged across all patients included in the study, the cost of subacute care and rehabilitation was R3 231 for patients treated with NPWTi-d vs R12 317 for patients treated with NPWT, including product costs of R2482 and R10 749, respectively. This finding may incentivize payers to cover the additional costs of NPWTi-d, particularly if they will benefit from downstream savings in treatment expenses. Although the overall treatment costs were higher for patients with NPWTi-d due to significantly higher costs incurred during the index admission, it is unclear whether the differences in costs can be attributed to wound care, whereas included subacute and rehabilitation visits were for wound care as indicated by ICD-10 codes and/or the use of NPWTi-d or NPWT.

Most importantly, the observed decrease in wound-related follow-up care for patients who received NPWTi-d may indicate more efficient and effective patient care and could result in improved quality of life. Access to affordable transportation is lacking in some areas of South Africa, making it difficult for patients to attend follow-up visits for wound care.1 Delays in wound healing cause patients additional pain and physical impairment as well as social, psychological, and economic burden.25,26 Wounds may have high levels of exudate and malodor, which can result in negative body image, reduced self-

esteem, and social isolation.25,26 Patients with hard-to-heal wounds may be unable to perform daily activities or return to work, and may require caregiving from family and friends.25,26 Thus, it is important to optimize clinical pathways for wound treatment to help accelerate the healing process and reduce the social and economic burden of wounds on patients and caregivers. The findings of this study suggest that NPWTi-d may provide a means to reduce follow-up wound care and overall LOT.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Data were obtained from a claims dataset. Patients were not randomized to NPWTi-d or NPWT, and there was likely a selection bias underlying the choice of therapy. Despite attempts to control for differences between groups with propensity score matching, patients could only be matched on documented variables. It is likely that patients who received NPWTi-d had more complex wounds and concomitant conditions than patients who received NPWT, which likely contributed to significant differences in initial hospital LOS and costs between groups. There was a lack of wound-specific data in the claims dataset, and study outcomes were limited to health care utilization and costs. There was likely variation in use of NPWTi-d and NPWT across the included facilities, including treatment protocols, timing of therapy initiation, and discharge criteria. Given that study data were obtained from a single South African insurer, albeit one with a large market share, and given the intrinsic challenges to wound care in the region, results may not be generalizable within or outside the country.

Conclusion

The findings from this study suggest that use of NPWTi-d may reduce wound-related subacute care and rehabilitation visits and costs for some patients following hospitalization. Reductions in downstream health care utilization not only result in potential cost savings for payers but also may indicate more efficient and effective care for patients. Despite its limitations, this study suggests that NPWTi-d may accelerate the wound healing process and raises additional questions about decision criteria for use of NPWTi-d in wound treatment. More studies are needed to fully assess how NPWTi-d affects wound care pathways, patient outcomes, and costs in South Africa and how it can be used to optimize healing.

Author & Publication Information

Authors: Maeyane S. Moeng, MBBCh (Wits), Dip PEC (SA), H Dip Surg (SA)1; Suleman Vadia, MBChB, FC Plastic Surgery2; Ashley W. Collinsworth, ScD, MPH3; Siobhan Lookess, BSc, PGDip³; and Paolo Capelli, Laurea3

Affiliations: 1University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa; 2Netcare Milpark Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa; ³Solventum, Maplewood, MN, USA

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Julie Robertson, PhD (an employee of Solventum), for assistance with manuscript editing. The final manuscript has been seen and approved by all authors, and the authors accept full responsibility for the design and conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Disclosure: M.S.M. and S.V. are consultants for Solventum. A.W.C., S.L., and P.C. are employees of Solventum.

Ethical Approval: Owing to its retrospective nature and the utilization of de-identified data, this study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review.

Correspondence: Ashley W. Collinsworth, 12930 W Interstate 10, San Antonio, TX 78249; ACollinsworth@solventum.com

Manuscript Accepted: September 18, 2025

References

1. Naude L, Balenda G, Lombaard A. Autologous whole blood clot and negative-pressure wound therapy in South Africa: a comparison of the cost and social considerations. S Afr Med J. 2022;112(10):800-805. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v112i10.16527

2. Bruwer FA, Botma Y, Mulder M. The ears of a hippopotamus: quality of venous leg ulcer care in Gauteng, South Africa. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020;33(2):84-90. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000617848.46377.ae

3. OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. 2023. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2023_7a7afb35-en.html

4. Bush L, Hendrikse C, Van Koningsbruggen C, Evans K. The burden and outcomes of firearm injuries at two district-level emergency centres in Cape Town, South Africa: a descriptive analysis. S Afr Med J. 2024;114(2):e1176. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2024.v114i2.1176

5. Bruwer FA, Karinos N, Adams K, Weir G, Sander J. The use of negative pressure wound therapy: recommendations by the Wound Healing Association of Southern Africa (WHASA). Wound Healing Southern Africa. 2021;14(2):40-51.

6. Kanapathy M, Mantelakis A, Khan N, Younis I, Mosahebi A. Clinical application and efficacy of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2020;17(6):1948-1959. doi:10.1111/iwj.13487

7. Anchalia M, Upadhyay S, Dahiya M. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time and standard negative pressure wound therapy in complex wounds: are they complementary or competitive? Wounds. 2020;32(12):E84-e91.

8. Diehm YF, Loew J, Will PA, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d) with V. A. C. VeraFlo in traumatic, surgical, and chronic wounds-a helpful tool for decontamination and to prepare successful reconstruction. Int Wound J. 2020;17(6):1740-1749. doi:10.1111/iwj.13462

9. Kim PJ, Silverman R, Attinger CE, Griffin L. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy with and without instillation of saline in the management of infected wounds. Cureus. 2020;12(7):e9047. doi:10.7759/cureus.9047

10. Silverman RP. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time: mechanisms of action literature review. Eplasty. 2023;23:e54.

11. Apelqvist J, Willy C, Fagerdahl AM, et al. EWMA document: negative pressure wound therapy. J Wound Care. 2017;26(Sup3):S1-S154. doi:10.12968/jowc.2017.26.Sup3.S1

12. Acosta J, Galarza L, Marsh M, Martinez RR, Eells M, Collinsworth AW. Effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell in removing nonviable tissue, promoting granulation tissue, and reducing surgical debridements: a systematic literature review. Wound Repair Regen. 2025;33(4):e70059. doi:10.1111/wrr.70059

13. Gabriel A, Camardo M, O’Rorke E, Gold R, Kim PJ. Effects of negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation versus standard of care in multiple wound types: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(1S-1):68S-76S. doi:10.1097/prs.0000000000007614

14. Gabriel A, Kahn K, Karmy-Jones R. Use of negative pressure wound therapy with automated, volumetric instillation for the treatment of extremity and trunk wounds: clinical outcomes and potential cost-effectiveness. Eplasty. 2014;14:e41.

15. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Steinberg JS, et al. The impact of negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation compared with standard negative-pressure wound therapy: a retrospective, historical, cohort, controlled study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(3):709-716. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000438060.46290.7a

16. Yang C, Goss SG, Alcantara S, Schultz G, Lantis II JC. Effect of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation on bioburden in chronically infected wounds. Wounds. 2017;29(8):240-246.

17. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Constantine T, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy with instillation: international consensus guidelines update. Int Wound J. 2020;17(1):174-186. doi:10.1111/iwj.13254

18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The VAC Veraflo Therapy system for acute infected or chronic wounds that are failing to heal. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg54/resources/the-vac-veraflo-therapy-system-for-acute-infected-or-chronic-wounds-that-are-failing-to-heal-pdf-64372116244165

19. World Health Organization. ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nd ed. 2004. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42980

20. Kline A, Lou Y. PsmPy: a package for retrospective cohort matching in Python. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2022;2022:1354-1357.

21. Omar M, Gathen M, Liodakis E, et al. A comparative study of negative pressure wound therapy with and without instillation of saline on wound healing. J Wound Care. 2016;25(8):475-478. doi:10.12968/jowc.2016.25.8.475

22. Collinsworth AW, Griffin LP. The effect of timing of instillation therapy on outcomes and costs for patients receiving negative pressure wound therapy. Wounds. 2022;34(11):269-275. doi:10.25270/wnds/22013

23. De Pellegrin L, Feltri P, Filardo G, et al. Effects of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d) versus NPWT or standard of care in orthoplastic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2023;20(6):2402-2413. doi:10.1111/iwj.14072

24. Kim PJ, Lavery LA, Galiano RD, et al. The impact of negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation on wounds requiring operative debridement: pilot randomised, controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2020;17(5):1194-1208. doi:10.1111/iwj.13424

25. Gupta S, Sagar S, Maheshwari G, Kisaka T,

Tripathi S. Chronic wounds: magnitude, socioeconomic burden and consequences. Wounds Asia. 2021;4(1):8-14.

26. Vowden P, Vowden K. The economic impact of hard-to heal wounds: promoting practice change to address passivity in wound management. Wounds International. 2016;7(2):10-15.