Phytotherapy for Chronic Wound Management in the Era of Antibiotic Resistance

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Chronic wounds, which exhibit prolonged inflammation, impaired healing, and vulnerability to infections, remain a global health challenge, largely driven by the persistence of microbial biofilms and escalating antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Biofilm protects pathogens from the host’s immune defenses and conventional antibiotic treatments, sustaining wound chronicity and fostering resistance. Due to the inefficacy of traditional antibiotics in penetrating biofilms and mitigating resistant strains, alternative therapeutic strategies are urgently required. Objective. To review the literature on the use of phytocompounds in chronic wound care. Methods. Various databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science were thoroughly surveyed by using keywords “phytocompounds, chronic wounds, wound healing, antimicrobial activity, antibiofilm activity and phytotherapy.” Results. Findings indicate that the compounds, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids, target various biological pathways, disrupt quorum sensing, and suppress virulence factors, making them valuable for disrupting biofilms and managing AMR. Phytocompounds such as coumarin, tannic acid, resveratrol, and berberine have the potential to enhance wound healing by reducing oxidative stress, promoting clotting, stimulating collagen synthesis, and combating infection. This review highlights complications associated with chronic wounds and explores beneficial phytocompounds for their management. Conclusion. Phytotherapy may play a role in managing wounds by promoting healing, preventing infection, and reducing the need for resistant antibiotics. Combining natural agents with traditional treatments presents a novel and integrative pathway to overcome the limitations posed by antibiotic resistance and biofilm-associated chronicity. While current findings are promising, further validation is needed to fully establish their clinical applications.

Plants and phytocompounds exhibit wound healing properties, promoting tissue regeneration and preventing chronic wounds. Many phytoconstituents possess antioxidant and antibacterial properties and can activate the pathways responsible for skin repair.1 Phytoconstituents also stimulate cytokine production, particularly interleukin (IL) 1β, which is important for the early-phase innate response, the chemotactic factor platelet-

derived growth factor (PDGF), growth factors, transforming growth factor (TGF) β, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), which affect the proliferating activity of fibroblasts and keratinocytes and help in tissue regeneration and wound healing.2

Phytocompounds offer biocompatibility, low toxicity, and a low-cost profile, supporting their clinical potential.3 A combination of phytocompounds often demonstrates enhanced antimicrobial and healing effects by working synergistically for chronic wound healing.

The current literature review emphasizes factors that delay chronic wound healing and provides information regarding plant-derived phytochemicals with antimicrobial and wound healing activity.4 It highlights the therapeutic potential of phytocompounds individually and in synergistic combinations for chronic wound healing.

Mechanism and Classification of Wound Healing

Wound healing represents a complex biological process that is characterized by intricate interactions among various cell types and the extracellular matrix (ECM). The repair mechanism is governed by soluble mediators, including growth factors and cytokines, which coordinate the sequential yet overlapping phases of healing.5 A deviation from these stages is observed in chronic wounds, which remain arrested in a prolonged pro-inflammatory phase. Wounds can be categorized based on origin, tissue involvement, and the method of closure as acute or chronic wounds. Acute wound infections arise when active bacteria in planktonic form penetrate healthy tissue within the wound.6 Unlike acute wounds, chronic wounds are marked by a prolonged healing process, often complicated by age, diabetes, vascular diseases, obesity, malnutrition, and mechanical stress. These wounds, frequently encountered in elderly individuals or in those with the aforementioned conditions, tend to be colonized by polymicrobial communities, forming biofilms that hinder wound repair. Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) stands out as the most common pathogen in chronic wounds, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa; other notable bacteria include Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.7,8 The diminished migratory capacity of cells, persistent inflammation, elevated proteolytic enzyme activity, and concurrent reduction in protease inhibitors are key features distinguishing chronic wounds from their acute counterparts.9

Methods

A comprehensive literature survey was conducted using PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science databases by using the keywords “phytocompounds, chronic wounds, wound healing, antimicrobial activity, antibiofilm activity, and phytotherapy”. The search covered publications from January 2000 to June 2025. Articles were screened for relevance, focusing on peer-reviewed experimental studies and clinical trials directly related to phytocompounds and wound healing.

Phases of Wound Healing

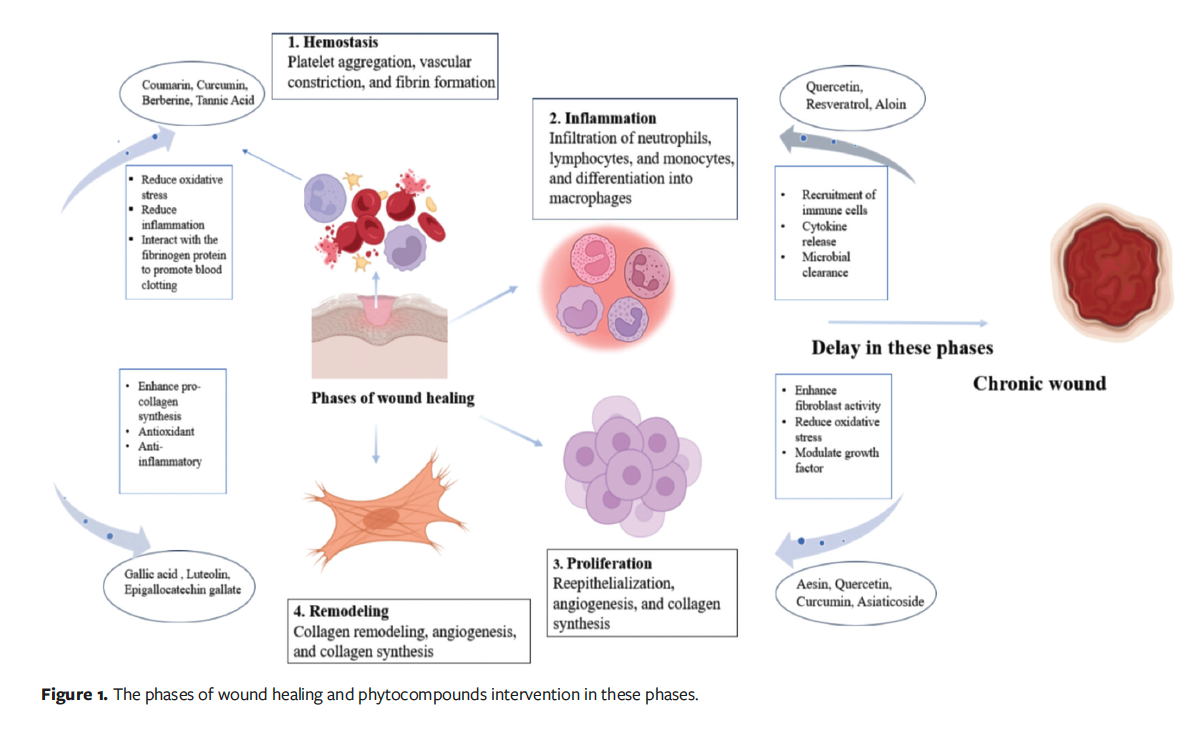

Figure 1 shows the 4 phases of wound healing: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling.

Hemostasis phase

The initial phase, hemostasis, occurs immediately after injury and typically lasts from minutes to a few hours, and this is followed by the inflammatory phase, which generally lasts 1 to 3 days but can extend to 5 to 7 days in some cases.10 As soon as injury occurs healing starts, and discharge of lymphatic fluids and blood occurs, leading to hemostasis. To prevent further blood loss, intrinsic and extrinsic pathways are activated. At the endothelial injury site, platelets start aggregating because of arterial vasoconstriction and release of adenosine 5'-diphosphate, which leads to thrombus formation.11,12 Growth factors such as VEGF, PDGF, bFGF, and TGF-α and -β stimulate cell proliferation and the production of ECM components in the skin, thereby supporting wound healing.13 Coumarin, a benzopyrone compound, helps in hemostasis by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation at the injury site. Coumarin may stabilize the vascular environment and support early clot formation. Its vasodilatory properties may improve blood flow around the wound, facilitating the delivery of clotting factors and promoting tissue repair.14,15 Tannic acid facilitates healing by interacting with fibrinogen to promote blood clotting; additionally, it can aid in wound contraction, scavenging free radicals, and stimulating capillary and fibroblast growth.16 Curcumin contributes to the hemostasis phase by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, which stabilizes early blood clots and creates a favorable environment for subsequent tissue repair.17 Berberine may support hemostasis by promoting vascular regeneration and stabilizing blood vessels. Its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory actions may further protect the wound during early healing phase.18

Inflammatory phase

In wound formation, inflammation is accelerated through the release of cytokines and mediators by white blood cells (WBCs) and platelets. Activated platelets release mediators such as serotonin and histamine, which increase vascular permeability and allow the migration of immune and repair cells into the wound site. WBCs consist of lymphocytes, which are important modulators during inflammation, and thus aid in the transition to the subsequent healing phases. Fibroblasts begin to appear 3 to 4 days after injury and migrate along the fibrin matrix formed during the inflammatory phase.19 Neutrophils help in wound decontamination by phagocytosing invading pathogens and clearing cellular debris, thus preparing the wound bed for subsequent healing processes. Monocytes and endothelial cells also attach to the fibrin matrix.20 Under the influence of growth factors from macrophages, fibroblasts proliferate and produce essential components such as glycosaminoglycans and collagen for the granulation tissue matrix. As macrophages decrease, fibroblasts also produce their growth factors, organize collagen into fibers, and create a matrix that supports cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation and strengthens the wounded area.21

Resveratrol reduces inflammation by suppressing cyclooxygenase enzymes and decreasing oxidative stress. It reduced neutrophil infiltration and cytokine production in acute wounds in animal models.22 Some natural phytocompounds, including curcumin and quercetin, are recognized for their anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activity, which can assist in modulating the inflammatory process by reducing the pain and swelling usually seen in wounds.23,24 Aloin, a bioactive compound from aloe vera, accelerates wound healing by increasing fibroblast migration and enhances the production of extracellular matrix proteins, which may regulate tissue repair and reduce scar formation. Its antioxidant activity also inhibits oxidative stress, further supporting effective wound regeneration.25

Proliferation phase

The proliferation phase, which lasts 4 to 21 days, is a key stage in wound healing that involves tissue formation with the support of ECM and collagen.6 Keratinocytes at the edge of the wound start migrating after a few hours, whereas epithelial stem cells and root sheath of hair follicles start proliferating within 2 to 3 days of injury.26 Angiogenesis is a critical element of this phase and itself has 2 phases, comprising the formation of new vessels by sprouting and their subsequent anastomosis.27 Macrophages play a crucial role by producing VEGF necessary for vessel anastomosis. Macrophage-derived factors such as PDGF, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, IL-6, and TGF-β induce the activation of fibroblasts.28 IL-6 is crucial because, in its absence, inflammatory signaling is compromised, angiogenesis is defective, and collagen deposition and reepithelialization are suboptimal. Keratinocytes regulate fibroblast activity by secreting ECM proteins including fibronectin, tenascin C, and laminin 332, creating a feedback loop that aids continuous tissue regeneration.29 During this stage, oxidative stress reduction and modulation of growth factor activity are also essential, as they support balanced fibroblast activation and stable angiogenesis. Quercetin promotes wound healing by boosting collagen and fibronectin synthesis, thereby accelerating wound closure and supporting cell proliferation.30 Another compound, Aesin, contributes by enhancing fibroblast migration and angiogenesis, which facilitates granulation tissue formation.31 Curcumin also supports healing process by reducing oxidative stress and modulating growth factor signaling (eg, TGF-β, VEGF), creating a regenerative microenvironment.17 Asiaticoside, derived from Centella asiatica, stimulates collagen type 1 synthesis and supports neovascularization, strengthening tissue repair and reepithelialization.32

Remodeling phase

The remodeling phase facilitates the replacement of scar tissue with granulation by forming blood vessels.33 During this stage, newly produced tissue strengthens and becomes more pliable. Enhanced production of collagen improves the skin’s flexibility and resistance to tearing. Macrophages regain their ability to engulf debris during reepithelialization. Regulatory macrophages remove unnecessary ECM and cells essential for preventing infection during healing.20 Natural compounds such as epigallocatechin gallate can enhance pro-collagen synthesis to accelerate tissue regeneration and effectively heal wounds.34 Myricetin, a flavonoid, has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties. It helps regulate inflammatory cytokines and supports the restructuring of collagen fibers during wound healing.35

Luteolin reduces inflammation and oxidative stress, which supports tissue regeneration. It also enhances collagen synthesis and regulates the key signaling pathways involved in remodeling, contributing to better wound closure.36

Complications Associated With Chronic Wounds

Bacterial biofilms (BBFs) complicate chronic wounds, hinder treatment, and promote antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Bacterial infection depends on the bacterial species present, their virulence, and their ability to resist the host immune response.

Role of biofilm in chronic wound complications

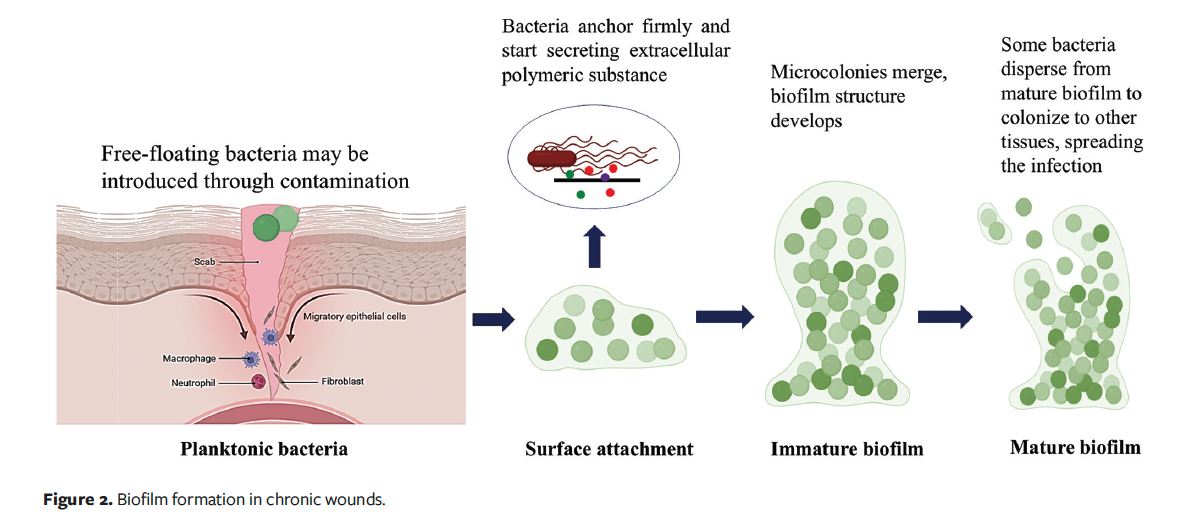

In a chronic wound, the BBF is a cohesive structure of bacteria that sticks to the wound bed and interacts with the ECM secreted by the film.37 Biofilm formation is the key reason for many chronic infections, leading to treatment failure and recurrence of multidrug resistance.38 The transition from free-floating planktonic bacteria to biofilm formation involves a complex system of signaling, spatial reorganization, and changes in gene expression.39 BBF exhibits growth similar to plankton cells, and as the bacteria expand, they adjust to their surroundings.40 Biofilm formation includes adherence of the microorganisms to a surface; their proliferation results in microcolony formation, leading to growth and differentiation41 (Figure 2). Extracellular DNA, proteins, polysaccharides, water, and other elements are the primary constituents of BBF, contributing to its structure, integrity, and function.42 Bacteria and endotoxins increase the number of inflammatory mediators, which leads to a never-ending cycle of wound inflammation.43

Patients are severely affected by biofilm infections because they are difficult to heal and delay patients’ recovery.44 Compared to planktonic cells, biofilms are more resilient due to several features, such as high cell density, low growth rates, persister cells, nutrition oxygen gradients, efflux pumps, horizontal gene transfer, and high mutation rates. In chronic wounds, necrotic tissue and debris facilitate the attachment of bacteria, which provide a favorable environment for biofilm formation.45 Biofilm formation acts as a mechanical barrier, causing resistance to topical and systemic antibiotics due to the exopolysaccharide (EPS) matrix. Biofilm prevents the entry of antibiotics, and it also transfers the plasmid-mediated antimicrobial resistance gene.46 Biofilms can elevate IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, and TNF-α; can trigger chronic inflammation; and can lead to wound bed senescence due to oxidative stress and protease-mediated degradation of receptors and cytokines.47

Phytocompounds have antibiofilm and antimicrobial activity with a nontoxic nature and biocompatibility.48,49 Several phytocompounds act as signal molecule antagonists by competing at their receptor binding sites to halt quorum-sensing pathways.48,49 Inhibiting such pathways can check biofilm growth by preventing the formation of adhesins as well as extracellular polymeric substances. Furthermore, phytochemicals can suppress bacterial pathogenicity through the downregulation of crucial factors that control host tissue invasion, immune escape, and virulence.48,49 It has been observed that phytocompounds can inhibit biofilm formation by regulating quorum-sensing mechanisms and nucleotide-based secondary messengers.50

Quorum sensing is a chemical signaling system among bacterial cells that regulates biofilm formation by altering various cellular processes.51 Phytocompounds such as quercetin may impede biofilm formation by blocking bacterial adhesion, reducing EPS production, altering cell surface hydrophobicity, and also preventing colonization by disrupting quorum-sensing pathways.52 Coumarin is another phytocompound that may act by influencing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel activity, and serine protease action.53

Antibiotic resistance: a critical challenge in wound care management

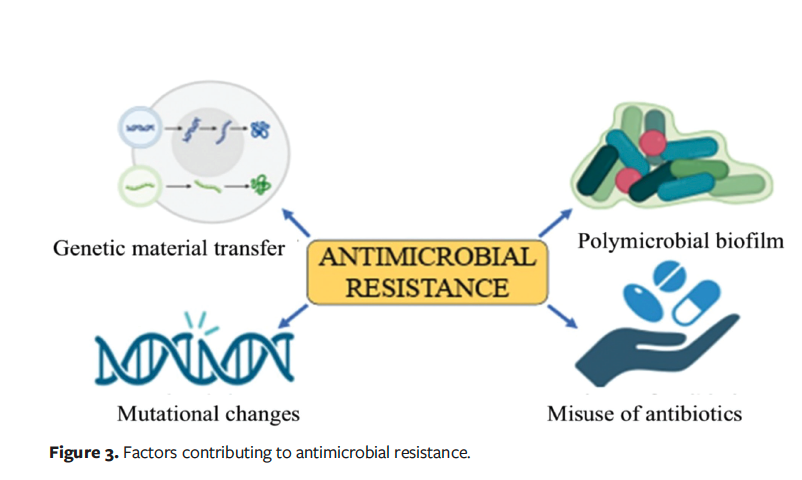

AMR occurs as microorganisms naturally evolve resistant strains through erroneous replication or the exchange of resistant traits. This phenomenon is exacerbated by the misuse and overuse of antimicrobial agents, which accelerates the development of drug-resistant strains (Figure 3). Factors such as inadequate infection control, poor sanitation, and improper food handling contribute to the further proliferation of resistant microorganisms. Globally, the emergence and dissemination of new resistance mechanisms threaten the effectiveness of standard treatments for common infectious diseases. AMR can result in increased mortality and disability among individuals who would otherwise recover. As AMR spreads, many medical procedures once considered safe now carry heightened risks without effective antimicrobial treatments.54

Systemic antibiotic therapy may be necessary for infected wounds; however, its improper use may increase antibiotic resistance and adverse effects. The increase in multidrug resistance is also cause for alarm. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the most often encountered multidrug-resistant pathogens include penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae and methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA).55 The World Health Organization estimated that resistance to antibiotics poses a danger to human health worldwide and might result in 10 million deaths yearly by the year 2050.56 Bacterial skin and subcutaneous tissue infections rank sixth globally in terms of infectious syndromes that result in deaths attributed to AMR.56 Microorganisms adapt to antibiotic treatment, leading to genetic modifications and their survival. The excessive use and misuse of antibiotics, incorrect diagnosis and prescription practice, diminished patient sensitivity, self-medication, and poor personal hygiene practice lead to resistance.57

Phytocompounds have garnered attention for their potential to combat antibiotic resistance and promote wound healing. Phytochemicals act through various mechanisms to combat resistance, for example, disruption of the bacterial membrane, inhibition of quorum sensing, and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.58,59 In a recent mouse model, quercetin and rutin demonstrated antibacterial, antibiofilm, and wound healing activities, and their combination with gentamycin enhanced the therapeutic outcomes.60 In a different study, berberine, an alkaloid, had a multifaceted mechanism of action, including intercalation into bacterial DNA, which may disrupt replication and transcription processes.61 It inhibited bacterial enzymes such as RNA polymerase, DNA gyrase, and topoisomerase, impeding nucleic acid synthesis, making berberine a promising phytochemical candidate for addressing antibiotic resistance.61

The prolonged healing processes of chronic wounds, which are frequently worsened by compromised vascularization, inflammation, and microbial colonization, pose considerable problems. The process of germs encasing themselves in a protective matrix, known as biofilm development, makes matters worse by obstructing wound healing and decreasing the efficacy of antimicrobial therapies. A wide range of bioactive compounds with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and wound healing characteristics are available to address these challenges, including curcumin, quercetin, coumarin, resveratrol, and bromelain.

Role of Phytotherapeutics in the Management of Chronic Wounds

Chronic wound persistence is largely due to prolonged inflammation and infection. The clinical management of chronic wounds continues to pose a significant challenge, notwithstanding substantial therapeutic advances. Several complications associated with traditional treatments must be addressed, including AMR, systemic toxicity, and severe adverse effects. These challenges highlight the necessity for developing secure and alternative pro-healing agents for efficient wound repair. The utilization of phytoconstituents has been embraced with considerable interest owing to their favorable safety profile and economic viability. The compounds modulate various signaling pathways, including TGF-β, NF-κB, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), enhancing wound repair. These constituents promote cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and angiogenesis while suppressing inflammation. Significant attention has been directed toward the development of diverse phytoconstituent-based topical delivery systems, including hydrogels, films, foams, sponges, fibers, and nanoformulations. These topical formulations enhance the pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties of phytoconstituents.62

Several studies have provided experimental support for the use of phytocompounds as effective agents in wound healing. Eugenol extracted from Cinnamomum tamala leaves was evaluated in a diabetic wound model in rats.63 Eugenol demonstrated enhanced wound contraction, granulation, and tensile strength due to its antidiabetic, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties. A well-structured murine study evaluated geraniol-loaded nanophytosomes that were coated with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA/Nphs-GNL) for their efficacy against MRSA-infected wounds.59 The study included detailed physicochemical characterization of the nanoparticles, robust control, and histological and molecular markers such as bFGF, COL1A, and CD31 to validate wound healing progression. In that study, the PVA/Nphs-GNL formulation reduced bacterial load, promoted granulation tissue formation, and increased proliferative markers. Though promising, the study’s limitation lies in the use of a murine model; human trials are necessary to establish the treatment’s efficacy and safety.64

Phytocompounds and their role in chronic wound healing

Phytocompounds are biological substances synthesized by plants. Nearly half of recent new chemical entities introduced into therapy were derived from natural products.65 Phytochemicals exhibit wound healing potential because of their anti-

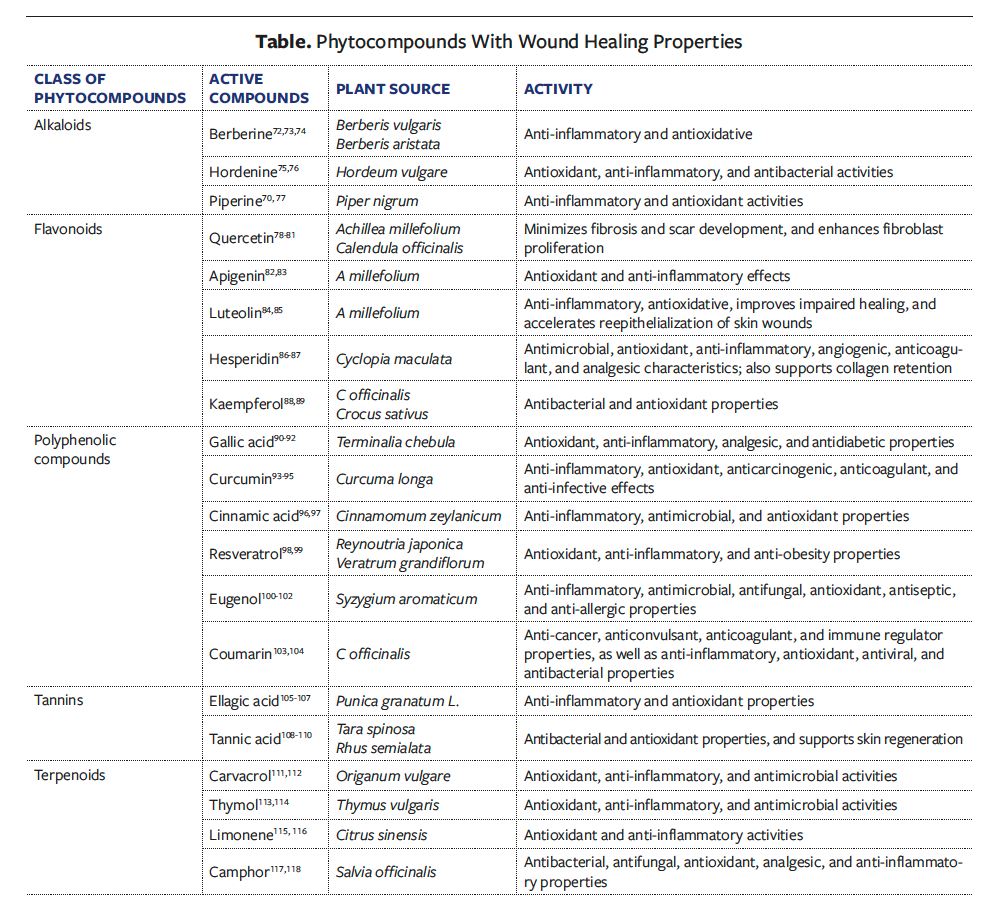

inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and platelet aggregation inhibition properties.65 Phytocompounds demonstrate significant wound healing potential because they enhance cellular processes essential for tissue repair and modulate critical biochemical pathways.66 Phytocompounds of various classes are being examined for their wound healing potential; these classes include flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, tannins, and polyphenols.

One of the noteworthy bioactive phytocompounds for chronic wounds is quercetin, a flavonoid, which can enhance wound healing by increasing hydroxyproline levels while also aiding bone generation and the repair of excisional wounds. In a murine model, quercetin also induced M2 macrophage polarization to help with diabetic wound healing and reduced the symptoms of atopic dermatitis.67 Topically administered quercetin in mouse models has been shown to prevent oxidative damage and to facilitate quicker wound healing through the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, MAPK, and NF-κB pathways.68 Piperine is an alkaloid with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties.69 Piperine has been shown to elevate TGF-β levels and promote collagen repair.70

Curcumin, a polyphenolic compound, has long been recognized for its wound healing potential; it exhibits antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-infective, and anti-inflammatory properties. Curcumin efficiently inhibits inflammation by its ability to modulate major inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-α, and it reduces oxidative stress by decreasing the expression of oxidative enzymes. In the proliferative phase, curcumin stimulates the migration of fibroblasts, promotes granulation tissue formation, and increases collagen deposition, thus enhancing reepithelialization. It triggers the expression of TGF-β that leads to the proliferation of fibroblasts and wound contraction in the remodeling stage of wound healing. All the combined actions make curcumin a powerful healing agent for tissue repair and regeneration.71 Phytocompounds recognized for their wound healing potential are listed in the Table.

The international trade of medicinal and aromatic plants has expanded substantially, with research reports indicating that their export and import value increased by nearly 98% from 2010 to 2023, reaching $4.18 billion in exports and $4.25 billion in imports.119 Additionally, the global plant extract market, valued at $33.9 billion in 2022, is projected to grow at an annual rate of 12%, reaching $94.1 billion by 2031.120 India’s phytochemical sector demonstrates 6.2% compound annual growth rate potential between 2023 and 2033, indicating substantial growth.120

Of the many phytocompounds that have been studied, a topical formulation of curcumin has shown promise in clinical evaluations for wound and ulcer management. Additionally, curcumin-based hydrogel dressings are under investigation for their wound healing potential due to their ability to promote collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and re-epithelialization. Although curcumin is not US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved as a stand-alone drug, it is incorporated in several FDA-registered topical medical devices and over-the-counter wound care formulations. For example, CuraMed (Terry Naturally by EuroPharma USA) and Curcumin C3 Complex (Sabinsa), used in nutraceutical and cosmeceutical formulations, are generally recognized as safe certified and are widely marketed for their therapeutic benefits.121,122

Bromelain, a proteolytic enzyme complex extracted from pineapple stems, has been clinically incorporated into topical formulations and wound dressings as NexoBrid (Vericel Corporation). A bromelain-based enzymatic debriding agent was approved by the FDA in December 2022 for eschar removal in burn wounds, which also has shown promise for chronic wound management due to its antimicrobial and tissue-preserving properties.123,124 In addition to their clinical efficacy, such phytocompound-based interventions offer a cost-effective alternative to conventional synthetic drugs. The studies cited in the current review span a broad spectrum, from in vitro assessments and animal models to early-phase clinical evaluations, indicating consistent biological activity and therapeutic potential. Although these findings are scientifically and methodologically validated before publication, a critical comparative analysis of their clinical significance, mechanistic pathways, and translational value is essential, and there is a need for clinical trials.

Combinatorial Therapy for Chronic Wound Management

It has been discovered that plant antimicrobials can enhance the effectiveness of conventional medications when used in combinations.125 In current clinical practice, different antibiotics combinations with diverse mechanisms of action can mitigate the emergence of antibiotic resistance and enhance treatment efficacy. Combination therapy can reduce toxicity, reduce resistance to drugs, achieve synergistic antimicrobial efficacy, and broaden the antibacterial range.126 Combination therapies involving β-lactamase inhibitors and antibiotics have shown effective counter-resistance. Combinations such as amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (Augmentin; GSK) and piperacillin with tazobactam (Tazocin; Pfizer) have been shown to effectively tackle resistant pathogens.127

Additionally, phytochemical-based drugs have gained attention due to plants’ ability to produce complex bioactive mixtures that can target multiple biological processes simultaneously, potentially increasing therapeutic efficiency.128 The efficacy of Helichrysum pedunculatum leaf extract combined with 8 different antibiotics against bacteria causing wound infections was reported in a study published in 2009.126 Results depicted significant antibacterial activity, with an 18-mm to 27-mm inhibition zone and minimum inhibitory concentration ranging between 0.1 mg/mL and 5.0 mg/mL. The combination of the compound and the antibiotic led to inhibition of the growth of bacteria, showing synergy.126

The synergistic interaction between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin, ibuprofen, diclofenac, and mefenamic acid with antibiotics such as cefuroxime and chloramphenicol was examined against MRSA.129 NSAIDs are recognized for their antibacterial properties and have been investigated as adjuncts to antibiotic therapy against MRSA. Specifically, ibuprofen and aspirin synergized when combined with cefuroxime against MRSA.129 That article also highlighted the potential of phytocompound-based synergistic therapies in managing chronic wounds, presenting both in vitro evidence and therapeutic relevance to support their integration into future clinical applications.

Limitations

Despite the increasing interest in phytotherapy in wound care, it has some major limitations, including unknown bioavailability in most compounds. There are almost no phase 1 safety trials, and there are no phase 2 dosing trials. The safety of these compounds is unclear. Clinical efficacy trials requiring prospective randomized controlled protocols of sufficient power to determine actual clinical efficacy are far away. Moreover, establishing accurate and consistent dosages remains difficult due to variability in composition. Future efforts should focus on standardized formulations, dosage, optimization, and well-designed clinical trials to ensure efficacy and safe therapeutic use.

Conclusion

Key phytocompounds, including terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids, have a variety of modes of action that include modulating inflammatory responses, targeting microbial pathogens, and promoting tissue regeneration. Advances in phytochemical analysis and screening continue to facilitate the discovery of novel phytocompounds from diverse plant sources, opening new avenues for chronic wound therapy. The road to adoption of these novel phytocompounds in Western medicine requires significant financial backing. To pursue meaningful phytotherapy research, sufficient capital must be leveraged to perform all the required steps that could potentially lead an agent or agents in this category to become recognized biopharmaceuticals that have a place in wound medicine

Author and Public Information

Authors: Kajal Rawat, MSc; and Reema Gabrani, PhD

Affiliations: Jaypee Institute of Information Technology, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to acknowledge the Jaypee Institute of Information Technology for infrastructure facilities and support.

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflict of interest.

Author Contributions: Kajal Rawat: Conceptualization, writing, editing, and figures. Reema Gabrani: Editing, reviewing and supervision.

Correspondence: Reema Gabrani, PhD; A 10, Sector 62, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, 201309; reema.gabrani@jiit.ac.in

Manuscript Accepted: August 7, 2025

References

1. Landge MM. Review of selected herbal phytoconstituents for wound healing treatment. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2024;13(3):208-215. doi:10.22271/phyto.2024.v13.i3c.14961

2. Tsioutsiou EE, Giachetti D, Miraldi E, Governa P, Magnano AR, Biagi M. Phytotherapy and skin wound healing. Acta Vulnologica. 2016;14(3):126-139.

3. Shedoeva A, Leavesley D, Upton Z, Fan C. Wound healing and the use of medicinal plants. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:2684108. doi:10.1155/2019/2684108

4. Cedillo-Cortezano M, Martinez-Cuevas LR, López JAM, Barrera López IL, Escutia-Perez S, Petricevich VL. Use of medicinal plants in the process of wound healing: a literature review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(3):303. doi:10.3390/ph17030303

5. Eming SA, Martin P, Tomic-Canic M. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(265):265sr6. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337

6. Sankar S, Kodiveri Muthukaliannan G. Deciphering the crosstalk between inflammation and biofilm in chronic wound healing: phytocompounds loaded bionanomaterials as therapeutics. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2024;31(4):103963. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2024.103963

7. Davis M, Hom D. Current and future developments in wound healing. Facial Plast Surg. 2023;39(5):477-488. doi:10.1055/s-0043-1769936

8. Malone M, Bjarnsholt T, McBain AJ, et al. The prevalence of biofilms in chronic wounds: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. J Wound Care. 2017;26(1):20-25. doi:10.12968/jowc.2017.26.1.20

9. Tan MLL, Chin JS, Madden L, Becker DL. Challenges faced in developing an ideal chronic wound model. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2023;18(1):99-114. doi:10.1080/17460441.2023.2158809

10. Hu Y, Yu L, Dai Q, Hu X, Shen Y. Multifunctional antibacterial hydrogels for chronic wound management. Biomater Sci. 2024;12(8):2460-2479. doi:10.1039/D4BM00155A

11. Ninan N, Thomas S, Grohens Y. Wound healing in urology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;82-83:93-105. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2014.12.002

12. Wallace HA, Basehore BM, Zito PM. Wound Healing Phases. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

13. Raziyeva K, Kim Y, Zharkinbekov Z, Kassymbek K, Jimi S, Saparov A. Immunology of acute and chronic wound healing. Biomolecules. 2021;11(5):700. doi:10.3390/biom11050700

14. Raj RK, Gunasekaran S, Gnanasambandan T, Seshadri S. Spectroscopic and theoretical studies of 4-chloro-3-formyl-6-methylcourmarin (4C3F6MC). Int J Curr Res Aca Rev. 2015;3(3):110-129.

15. desJardins-Park HE, Gurtner GC, Wan DC, Longaker MT. From chronic wounds to scarring: the growing health care burden of under- and over-healing wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2022;11(9):496-510. doi:10.1089/wound.2021.0039

16. Mohammadzadeh V, Mahmoudi E, Ramezani S,

Navaeian M, Taheri RA, Ghorbani M. Design of a novel tannic acid enriched hemostatic wound dressing based on electrospun polyamide-6/hydroxyethyl cellulose nanofibers. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023;86:104625. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2023.104625

17. Alven S, Nqoro X, Aderibigbe BA. Polymer-based materials loaded with curcumin for wound healing applications. Polymers (Basel). 2020;12(10):2286. doi:10.3390/polym12102286

18. Qiao W, Niu L, Jiang W, Lu L, Liu J. Berberine ameliorates endothelial progenitor cell function and wound healing in vitro and in vivo via the miR-21-3p/RRAGB axis for venous leg ulcers. Regen Ther. 2024;26:458-468. doi:10.1016/j.reth.2024.06.011

19. Holzer-Geissler JCJ, Schwingenschuh S, Zacharias M, et al. The impact of prolonged inflammation on wound healing. Biomedicines. 2022;10(4):856. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10040856

20. Rodrigues M, Kosaric N, Bonham CA, Gurtner GC. Wound healing: a cellular perspective. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):665-706. doi:10.1152/physrev.00067.2017

21. Ruszczak Z. Effect of collagen matrices on dermal wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55(12):1595-1611. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.003

22. de Sá Coutinho D, Pacheco MT, Frozza RL,

Bernardi A. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol: mechanistic insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1812. doi:10.3390/ijms19061812

23. Arifin AF, Rijal S, Idrus HH. Phytochemicals in medicinal plants in wound healing. International Journal of Medical Science and Dental Research. 2023;6(05):107-113.

24. Eshete MA, Molla EL. Cultural significance of medicinal plants in healing human ailments among Guji semi-pastoralist people, Suro Barguda District, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2021;17(1):61. doi:10.1186/s13002-021-00487-4

25. Dewi NP, Vedora MP, Vani AT, Abdullah D, Triansyah I. Effect of aloin extract on the increase of fibroblast cell expression on healing of wound wounds of horse white rats (Rattus norvegicus) by the aging process. MSJ: Majority Science Journal. 2023;1(4):171-179. doi:10.61942/msj.v1i4.92

26. Lau K, Paus R, Tiede S, Day P, Bayat A. Exploring the role of stem cells in cutaneous wound healing. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(11):921-933. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00942.x

27. Affolter M, Zeller R, Caussinus E. Tissue remodelling through branching morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(12):831-842. doi:10.1038/nrm2797

28. Fantin A, Vieira JM, Gestri G, et al. Tissue macrophages act as cellular chaperones for vascular anastomosis downstream of VEGF-mediated endothelial tip cell induction. Blood. 2010;116(5):829-840. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-12-257832

29. Iorio V, Troughton LD, Hamill KJ. Laminins: roles and utility in wound repair. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4(4):250-263. doi:10.1089/wound.2014.0533

30. Gopalakrishnan A, Ram M, Kumawat S, Tandan S, Kumar D. Quercetin accelerated cutaneous wound healing in rats by increasing levels of VEGF and TGF-β1. Indian J Exp Biol. 2016;54(3):187-195.

31. Zhang L, Wang H, Wang T, et al. Potent anti-inflammatory agent escin does not affect the healing of tibia fracture and abdominal wound in an animal model. Exp Ther Med. 2012;3(4):735-739. doi:10.3892/etm.2012.467

32. Hou Q, Li M, Lu YH, Liu DH, Li CC. Burn wound healing properties of asiaticoside and madecassoside. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(3):1269-1274. doi:10.3892/etm.2016.3459

33. Xue M, Jackson CJ. Extracellular matrix reorganization during wound healing and its impact on abnormal scarring. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4(3):119-136. doi:10.1089/wound.2013.0485

34. Agize M, Asfaw Z, Nemomissa S, Gebre T. Ethnobotany of traditional medicinal plants and associated indigenous knowledge in Dawuro Zone of Southwestern Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2022;18(1):48. doi:10.1186/s13002-022-00546-4

35. Sklenářová R, Svrčková M, Hodek P, Ulrichová J, Franková J. Effect of the natural flavonoids myricetin and dihydromyricetin on the wound healing process in vitro. J Appl Biomed. 2021;19(3):149-158. doi:10.32725/jab.2021.017

36. Siaghi M, Karimizade A, Mellati A, et al. Luteolin-

incorporated fish collagen hydrogel scaffold: an effective drug delivery strategy for wound healing. Int J Pharm. 2024;657:124138. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124138

37. Wei D, Zhu XM, Chen YY, et al. Chronic wound biofilms: diagnosis and therapeutic strategies. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(22):2737-2744. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000523

38. Harika K, Shenoy VP, Narasimhaswamy N, Chawla K. Detection of biofilm production and its impact on antibiotic resistance profile of bacterial isolates from chronic wound infections. J Glob Infect Dis. 2020;12(3):129-134. doi:10.4103/jgid.jgid_150_19

39. Goswami AG, Basu S, Banerjee T, Shukla VK. Biofilm and wound healing: from bench to bedside. Eur J Med Res. 2023;28(1):157. doi:10.1186/s40001-023-01121-7

40. Koo H, Allan RN, Howlin RP, Stoodley P, Hall-

Stoodley L. Targeting microbial biofilms: current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(12):740-755. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2017.99

41. Diban F, Di Lodovico S, Di Fermo P, et al. Biofilms in chronic wound infections: innovative antimicrobial approaches using the in vitro Lubbock chronic wound biofilm model. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2):1004. doi:10.3390/ijms24021004

42. Jensen PØ, Kolpen M, Kragh KN, Kühl M. Microenvironmental characteristics and physiology of biofilms in chronic infections of CF patients are strongly affected by the host immune response. APMIS. 2017;125(4):276-288. doi:10.1111/apm.12668

43. Seth AK, Geringer MR, Hong SJ, Leung KP, Mustoe TA, Galiano RD. In vivo modeling of biofilm-infected wounds: a review. J Surg Res. 2012;178(1):330-338. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2012.06.048

44. Puca V, Marulli RZ, Grande R, et al. Microbial species isolated from infected wounds and antimicrobial resistance analysis: data emerging from a three-years retrospective study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(10):1162. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10101162

45. Zhao G, Usui ML, Lippman SI, et al. Biofilms and inflammation in chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013;2(7):389-399. doi:10.1089/wound.2012.0381

46. Di Domenico EG, Farulla I, Prignano G, et al. Biofilm is a major virulence determinant in bacterial colonization of chronic skin ulcers independently from the multidrug resistant phenotype. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(5):1077. doi:10.3390/ijms18051077

47. Li P, Tong X, Wang T, et al. Biofilms in wound healing: a bibliometric and visualised study. Int Wound J. 2023;20(2):313-327. doi:10.1111/iwj.13878

48. Hrynyshyn A, Simões M, Borges A. Biofilms in surgical site infections: recent advances and novel prevention and eradication strategies. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(1):69. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11010069

49. Ghosh S, Lahiri D, Nag M, et al. Phytocompound mediated blockage of quorum sensing cascade in ESKAPE pathogens. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(1):61. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11010061

50. Prakash B, Veeregowda BM, Krishnappa.G. Biofilms: a survival strategy of bacteria. Curr Sci. 2003;85(9):1299-1307.

51. Brooun A, Liu S, Lewis K. A dose-response study of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(3):640-646. doi:10.1128/AAC.44.3.640-646.2000

52. Mu Y, Zeng H, Chen W. Quercetin inhibits biofilm formation by decreasing the production of EPS and altering the composition of EPS in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:631058. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.631058

53. Neelgundmath M, Dinesh KR, Mohan CD, et al. Novel synthetic coumarins that targets NF-κB in hepatocellular carcinoma. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25(4):893-897. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.065

54. Huttner A, Harbarth S, Carlet J, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: a global view from the 2013 World Healthcare-Associated Infections Forum. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2013;2(1):31. doi:10.1186/2047-2994-2-31

55. Hernandez R. The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of chronic wounds. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19(6):326-337. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00091.x

56. Monk EJM, Jones TPW, Bongomin F, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in bacterial wound, skin, soft tissue and surgical site infections in Central, Eastern, Southern and Western Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024;4(4):e0003077. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0003077

57. Uddin TM, Chakraborty AJ, Khusro A, et al. Antibiotic resistance in microbes: history, mechanisms, therapeutic strategies and future prospects. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(12):1750-1766. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2021.10.020

58. Silva E, Teixeira JA, Pereira MO, Rocha CMR, Sousa AM. Evolving biofilm inhibition and eradication in clinical settings through plant-based antibiofilm agents. Phytomedicine. 2023;119:154973. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154973

59. Harakeh S, Khan I, Almasaudi SB, Azhar EI, Al-Jaouni S, Niedzweicki A. Role of nutrients and phyto-compounds in the modulation of antimicrobial resistance. Curr Drug Metab. 2017;18(9):858-867. doi:10.2174/1389200218666170719095344

60. Almuhanna Y, Alshalani A, AlSudais H, et al. Antibacterial, antibiofilm, and wound healing activities of rutin and quercetin and their interaction with gentamicin on excision wounds in diabetic mice. Biology (Basel). 2024;13(9):676. doi:10.3390/biology13090676

61. Yadav H, Mahalvar A, Pradhan M, Yadav K, Kumar Sahu K, Yadav R. Exploring the potential of phytochemicals and nanomaterial: a boon to antimicrobial treatment. Med Drug Discov. 2023;17:100151. doi:10.1016/j.medidd.2023.100151

62. Pattnaik S, Mohanty S, Sahoo SK, Mohanty C. A mechanistic perspective on the role of phytoconstituents-based pharmacotherapeutics and their topical formulations in chronic wound management. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2023;84:104546. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2023.104546

63. Soni R, Mehta NM, Srivastava DN. Wound repair and regenerating effect of ethyl acetate soluble fraction of ethanolic extract of Cinnamomum tamala leaves in diabetic rats. Eur J Exp Biol. 2013;3(3):43-47.

64. Babaei P, Farahpour MR, Tabatabaei ZG. Fabrication of geraniol nanophytosomes loaded into polyvinyl alcohol: a new product for the treatment of wounds infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Tissue Viability. 2024;33(1):116-125. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2023.11.002

65. Khaire M, Bigoniya J, Bigoniya P. An insight into the potential mechanism of bioactive phytocompounds in the wound management. Pharmacogn Rev. 2023;17(33):43-68. doi:10.5530/097627870153

66. Thangapazham RL, Sharad S, Maheshwari RK. Phytochemicals in wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2016;5(5):230-241. doi:10.1089/wound.2013.0505

67. Fu J, Huang J, Lin M, Xie T, You T. Quercetin promotes diabetic wound healing via switching macrophages from M1 to M2 polarization. J Surg Res. 2020;246:213-223. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2019.09.011

68. Salehi B, Machin L, Monzote L, et al. Therapeutic potential of quercetin: new insights and perspectives for human health. ACS Omega. 2020;5(20):11849-11872. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c01818

69. Derosa G, Maffioli P, Sahebkar A. Piperine and its role in chronic diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;928:173-184. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41334-1_8

70. Alsareii SA, Ahmad J, Umar A, Ahmad MZ, Shaikh IA. Enhanced in vivo wound healing efficacy of a novel piperine-containing bioactive hydrogel in excision wound rat model. Molecules. 2023;28(2):545. doi:10.3390/molecules28020545

71. Farhat F, Sohail SS, Siddiqui F, Irshad RR, Madsen DØ. Curcumin in wound healing—a bibliometric analysis. Life (Basel). 2023;13(1):143. doi:10.3390/life13010143

72. Akhter MH, Al-Keridis LA, Saeed M, et al. Enhanced drug delivery and wound healing potential of berberine-loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite gel: characterization and in vivo assessment. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1238961. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1238961

73. Cometa S, Licini C, Bonifacio MA, Mastrorilli P, Mattioli-Belmonte M, De Giglio E. Carboxymethyl cellulose-based hydrogel film combined with berberine as an innovative tool for chronic wound management. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;283:119145. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119145

74. Wang F, Wang X, Hu N, Qin G, Ye B, He JS. Improved antimicrobial ability of dressings containing berberine loaded cellulose acetate/hyaluronic acid electrospun fibers for cutaneous wound healing. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2022;18(1):77-86. doi:10.1166/jbn.2022.3225

75. Xu Z, Zhang Q, Ding C, et al. Beneficial effects of hordenine on a model of ulcerative colitis. Molecules. 2023;28(6):2834. doi:10.3390/molecules28062834

76. Vidyavarsha SJ, Kariyil BJ, Unni V, et al. In vitro antibacterial activity of andrographolide and hordenine against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus aureus. J Vet Anim Sci. 2022;53(3). doi:10.51966/jvas.2022.53.3.407-412

77. Alves FS, Cruz JN, de Farias Ramos IN, et al. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity effects of extracts of Piper nigrum L. and piperine. Separations. 2022;10(1):21. doi:10.3390/separations10010021

78. Doersch KM, Newell-Rogers MK. The impact of quercetin on wound healing relates to changes in αV and β1 integrin expression. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2017;242(14):1424-1431. doi:10.1177/1535370217712961

79. Nain A, Tseng YT, Gupta A, et al. NIR-activated quercetin-based nanogels embedded with CuS nanoclusters for the treatment of drug-resistant biofilms and accelerated chronic wound healing. Nanoscale Horiz. 2023;8(12):1652-1664. doi:10.1039/D3NH00275F

80. Mi Y, Zhong L, Lu S, et al. Quercetin promotes cutaneous wound healing in mice through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;290:115066. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2022.115066

81. Beken B, Serttas R, Yazicioglu M, Turkekul K,

Erdogan S. Quercetin improves inflammation, oxidative stress, and impaired wound healing in atopic dermatitis model of human keratinocytes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2020;33(2):69-79. doi:10.1089/ped.2019.1137

82. Salehi B, Venditti A, Sharifi-Rad M, et al. The therapeutic potential of apigenin. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):1305. doi:10.3390/ijms20061305

83. Ginwala R, Bhavsar R, Chigbu DI, Jain P, Khan ZK. Potential role of flavonoids in treating chronic inflammatory diseases with a special focus on the anti-inflammatory activity of apigenin. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019;8(2):35. doi:10.3390/antiox8020035

84. Chen LY, Cheng HL, Kuan YH, Liang TJ, Chao YY, Lin HC. Therapeutic potential of luteolin on impaired wound healing in streptozotocin-induced rats. Biomedicines. 2021;9(7):761. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9070761

85. Xi M, Hou Y, Wang R, et al. Potential application of luteolin as an active antibacterial composition in the development of hand sanitizer products. Molecules. 2022;27(21):7342. doi:10.3390/molecules27217342

86. Kodous AS, Abdel-Maksoud MA, El-Tayeb MA, et al. Hesperidin-loaded PVA/alginate hydrogel: targeting NFκB/iNOS/COX-2/TNF-α inflammatory signaling pathway. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1347420. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1347420

87. Rehman U, Sheikh A, Alsayari A, Wahab S,

Kesharwani P. Hesperidin-loaded cubogel as a novel therapeutic armamentarium for full-thickness wound healing. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2024;234:113728. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2023.113728

88. Al-Ghanayem AA, Alhussaini MSR, Asad M, Joseph B. Kaempferol promotes wound-healing in diabetic rats through antibacterial and antioxidant effects, devoid of proliferative action. Bioscience Journal. 2024;40:e40015. doi:10.14393/BJ-v40n0a2024-68974

89. Rofeal M, El-Malek FA, Qi X. In vitro assessment of green polyhydroxybutyrate/chitosan blend loaded with kaempferol nanocrystals as a potential dressing for infected wounds. Nanotechnology. 2021;32(37). doi:10.1088/1361-6528/abf7ee

90. Yang DJ, Moh SH, Son DH, et al. Gallic acid promotes wound healing in normal and hyperglucidic conditions. Molecules. 2016;21(7):899. doi:10.3390/molecules21070899

91. Yağcılar AP, Okur ME, Ayla Ş, et al. Development of new gallic acid loaded films for wound dressings: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024;102(5):106407. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2024.106407

92. Croitoru AM, Ayran M, Altan E, et al. Development of gallic acid-loaded ethylcellulose fibers as a potential wound dressing material. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(Pt 5):126996. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126996

93. Kumari A, Raina N, Wahi A, et al. Wound-healing effects of curcumin and its nanoformulations: a comprehensive review. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(11):2288. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14112288

94. Kiti K, Suwantong O. The potential use of curcumin-

β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex/chitosan-loaded cellulose sponges for the treatment of chronic wound. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164:3250-3258. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.190

95. Salehi B, Rodrigues CF, Peron G, et al. Curcumin nanoformulations for antimicrobial and wound healing purposes. Phytother Res. 2021;35(5):2487-2499. doi:10.1002/ptr.6976

96. Naghavi M, Tamri P, Soleimani Asl S. Investigation of healing effects of cinnamic acid in a full-thickness wound model in rabbit. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2021;16(1):e97669. doi:10.5812/jjnpp.97669

97. Mingoia M, Conte C, Di Rienzo A, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel cinnamic acid-based antimicrobials. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15(2):228. doi:10.3390/ph15020228

98. Hecker A, Schellnegger M, Hofmann E, et al. The impact of resveratrol on skin wound healing, scarring, and aging. Int Wound J. 2022;19(1):9-28. doi:10.1111/iwj.13601

99. Zhou X, Ruan Q, Ye Z, et al. Resveratrol accelerates wound healing by attenuating oxidative stress-induced impairment of cell proliferation and migration. Burns. 2021;47(1):133-139. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2020.10.016

100. Khadim H, Zeeshan R, Riaz S, et al. Development of eugenol loaded cellulose-chitosan based hydrogels; in-vitro and in-vivo evaluation for wound healing. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2024;693:134033. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.134033

101. Zhou R, Zhang W, Zhang Y, et al. Laponite/lactoferrin hydrogel loaded with eugenol for methicillin-

resistant Staphylococcus aureus-infected chronic skin wound healing. J Tissue Viability. 2024;33(3):487-503. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2024.05.006

102. Li M, Li F, Wang T, Zhao L, Shi Y. Fabrication of carboxymethylcellulose hydrogel containing β-cyclodextrin–eugenol inclusion complexes for promoting diabetic wound healing. J Biomater Appl. 2020;34(6):851-863. doi:10.1177/0885328219873254

103. Mohammad A, Hassanzadeh-Taheri M, Zardast M, Honarmand M. Efficacy of topical application of coumarin on incisional wound healing in BALB/c mice. Iranian Journal of Dermatology. 2020;23(2):56-63. doi:10.22034/ijd.2020.110925

104. Dutra FVA, Francisco CS, Carneiro Pires B, et al. Coumarin/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes promote acceleration and improvement of wound healing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(24):30900-30914. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c05069

105. Illescas-Montes R, Rueda-Fernández M, González-Acedo A, et al. Effect of punicalagin and ellagic acid on human fibroblasts in vitro: a preliminary evaluation of their therapeutic potential. Nutrients. 2023;16(1):23. doi:10.3390/nu16010023

106. Fan G, Xu Z, Tang J, Liu L, Dai R. Effect of ellagic acid on wound healing of chronic skin ulceration in diabetic mice and macrophage phenotype transformation. J Biomater Tissue Eng. 2019;9(8):1108-1113. doi:10.1166/jbt.2019.2116

107. Zhang T, Guo L, Li R, et al. Ellagic acid–cyclodextrin inclusion complex-loaded thiol–ene hydrogel with antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties for wound healing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(4):4959-4972. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c20229

108. Wekwejt M, Małek M, Ronowska A, et al. Hyaluronic acid/tannic acid films for wound healing application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;254(Pt 3):128101. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128101

109. Mndlovu H, du Toit LC, Kumar P, Choonara YE. Tannic acid-loaded chitosan-RGD-alginate scaffolds for wound healing and skin regeneration. Biomed Mater. 2023;18(4). doi:10.1088/1748-605X/acce88

110. Chen Y, Tian L, Yang F, et al. Tannic acid accelerates cutaneous wound healing in rats via activation of the ERK 1/2 signaling pathways. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2019;8(7):341-354. doi:10.1089/wound.2018.0853

111. Fauzian F, Garmana AN, Mauludin R. The efficacy of carvacrol loaded nanostructured lipid carrier in improving the diabetic wound healing activity: In vitro and in vivo studies. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2024;14(3):231-243. doi:10.7324/JAPS.2024.153862

112. Mir M, Permana AD, Ahmed N, Khan GM, Rehman AU, Donnelly RF. Enhancement in site-specific delivery of carvacrol for potential treatment of infected wounds using infection responsive nanoparticles loaded into dissolving microneedles: a proof of concept study. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2020;147:57-68. doi:10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.12.008

113. Najafloo R, Behyari M, Imani R, Nour S. A mini-review of thymol incorporated materials: applications in antibacterial wound dressing. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;60:101904. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2020.101904

114. Nagoor Meeran MF, Javed H, Al Taee H, Azimullah S, Ojha SK. Pharmacological properties and molecular mechanisms of thymol: prospects for its therapeutic potential and pharmaceutical development. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:830. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00380

115. Ahmad M, Khan TH, Ansari MN, Ahmad SF. Enhanced wound healing by topical administration of d-limonene in alloxan induced diabetic mice through reduction of pro-inflammatory markers and chemokine expression. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(Suppl 2):P29. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-S2-P29

116. d’Alessio PA, Mirshahi M, Bisson JF, Bene MC. Skin repair properties of d-Limonene and perillyl alcohol in murine models. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2014;13(1):29-35. doi:10.2174/18715230113126660021

117. Duda-Madej A, Viscardi S, Grabarczyk M, et al. Is camphor the future in supporting therapy for skin infections? Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(6):715. doi:10.3390/ph17060715

118. Smriti, Kumari N, Sharma VK. Efficacy of neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf extracts in combination with camphor with respect to wound healing in animals. The Pharma Innovation Journal. 2021;10(10):824-829.

119. Zamani S, Fathi M, Ebadi MT, Máthé Á. Global trade of medicinal and aromatic plants. A review. J Agric Food Res. 2025;21:101910. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2025.101910

120. Madhavi BLR, Pruthvi N, Chandur U, Sundari SP. Phytopharmaceutical industry in India: an insight towards its growth and sustenance. APTI Women’s Forum Newsletter. 2024;3(3). https://aptiwfn.com/abstracts/articledetail/4c081fd3673e4b2aa8b3d1f0003a9745

121. Kotha RR, Luthria DL. Curcumin: biological, pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and analytical aspects. Molecules. 2019;24(16):2930. doi:10.3390/molecules24162930

122. Hegde M, Girisa S, BharathwajChetty B, Vishwa R, Kunnumakkara AB. Curcumin formulations for better bioavailability: what we learned from clinical trials thus far? ACS Omega. 2023;8(12):10713-10746. doi:10.1021/acsomega.2c07326

123. Shoham Y, Gasteratos K, Singer AJ, Krieger Y,

Silberstein E, Goverman J. Bromelain-based enzymatic burn debridement: a systematic review of clinical studies on patient safety, efficacy and long-term outcomes. Int Wound J. 2023;20(10):4364-4383. doi:10.1111/iwj.14308

124. Doyno C. NexoBrid for eschar removal in thermal burns: anacaulase-bcdb improves current standard of care for deep partial thickness and/or full thickness thermal burns. Drug Topics. 2023;167(2):30-31.

125. Sibanda T, Okoh AI. The challenges of overcoming antibiotic resistance: plant extracts as potential sources of antimicrobial and resistance modifying agents. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6(25):2886-2896.

126. Aiyegoro OA, Afolayan AJ, Okoh AI. Synergistic interaction of Helichrysum pedunculatum leaf extracts with antibiotics against wound infection associated bacteria. Biol Res. 2009;42(3):327-338.

127. Abreu AC, McBain AJ, Simões M. Plants as sources of new antimicrobials and resistance-modifying agents. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29(9):1007-1021. doi:10.1039/c2np20035j

128. Abreu AC, Serra SC, Borges A, et al. Combinatorial activity of flavonoids with antibiotics against drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microb Drug Resist. 2015;21(6):600-609. doi:10.1089/mdr.2014.0252

129. Chan EWL, Yee ZY, Raja I, Yap JKY. Synergistic effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on antibacterial activity of cefuroxime and chloramphenicol against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;10:70-74. doi:10.1016/j.jgar.2017.03.012