Advancing Chronic Wound Care With Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Imaging: Clinical Applications, Measurement Parameters, and Insights Into Healing Dynamics

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Chronic wound management is a global health care challenge affecting patient morbidity and quality of life while presenting a substantial economic burden. A critical limitation in effective wound care is the inability to accurately assess microvascular tissue health in real time. This review of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) imaging and its use in wound care emphasizes relevant clinical end points and explores key measurement parameters assessed via NIRS imaging. Objective. To identify, describe, and illustrate NIRS imaging modalities and measurement parameters, and their clinical applications. Results. Clinical studies demonstrated that NIRS imaging can effectively detect poor wound healing early, facilitating timely interventions. Changes in parameters such as oxygenated hemoglobin, deoxygenated hemoglobin, and tissue oxygen saturation have shown strong correlations with wound healing progress, enabling clinicians to make more informed decisions. Conclusion. NIRS imaging advances wound management by providing real-time, noninvasive, and objective data on tissue oxygenation and perfusion. NIRS imaging may objectively complement the standard percentage area reduction assessments during the wound treatment process.

Vascular health is central to wound healing, with oxygen required for almost every step in the healing process.1,2 Despite the importance of vascular assessment, traditional vascular assessment methods, such as pulse volume recording (PVR), ankle-brachial index (ABI), toe brachial index (TBI), and transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TcPO₂), remain limited in their ability to provide real-time insights into the status of microvascular perfusion and oxygenation at the wound site. For example, ABI has conceptual limitations, such as compromised accuracy in individuals with arterial calcification.3 While PVR and TBI are often preferred in patients with calcified arteries,4,5 TBI is limited in patients with forefoot amputation, and PVR may lack accuracy in detecting distal arterial disease or in patients with congestive heart failure or low stroke volume. Moreover, PVR, ABI, and TBI evaluate macrocirculation in the larger vessels and do not provide insights into microcirculation.6 TcPO₂ measurement is used to evaluate microcirculation; however, it is limited to measuring periwound oxygenation because the electrodes must be placed on intact skin.

The microvasculature (vessels <100 µm in diameter) is essential for wound healing; it delivers the oxygen and nutrients required for tissue repair.6,7 Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) imaging offers real-time assessment of tissue oxygenation and microcirculation at wound sites and surrounding areas. This literature review of NIRS imaging in wound care highlights relevant clinical end points and key measurement parameters. The review was conducted by a panel of experts under the auspices of the Wound Care Collaborative Community (WCCC) Tools Work Group (TWG). The objective of the review is to identify, describe, and illustrate NIRS modalities, their measurement parameters, and their clinical applications.

Electromagnetic Spectrum and Near-Infrared Technologies

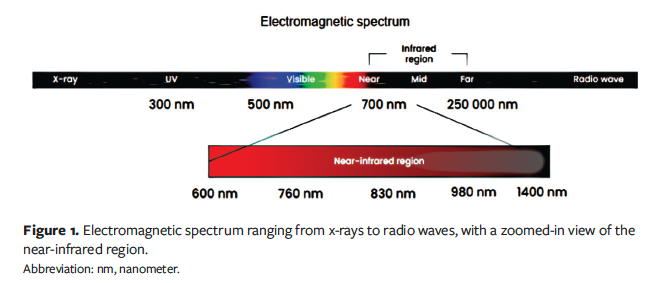

The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses a wide range of wavelengths, including the near-infrared (NIR) region.8 The NIR region is adjacent to the visible region and overlaps with the infrared (IR) region, which extends from about 0.6 µm to 1 mm-2 mm (Figure 1).

Spectroscopic techniques encompass a broad range of technologies that leverage spectroscopic principles. These techniques capture interactions between specific portions of the electromagnetic spectrum and the object (eg, human tissue). Spectral imaging combines spectroscopy with imaging, generating datasets consisting of multiple images of the same object, each captured at different wavelengths or spectral bands (range of wavelengths). NIRS imaging is a type of spectral imaging that utilizes the NIR region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

NIR light can penetrate biological tissues. A study utilizing mathematical modeling of human skin demonstrated that a wavelength of 633 nm penetrates to 1.8 mm, 660 nm penetrates to 2.0 mm, 850 nm penetrates to 2.4 mm, and 900 nm penetrates to 2.5 mm.8 Thus, NIRS penetration depth is commonly referenced as being approximately 2 mm to 3 mm.

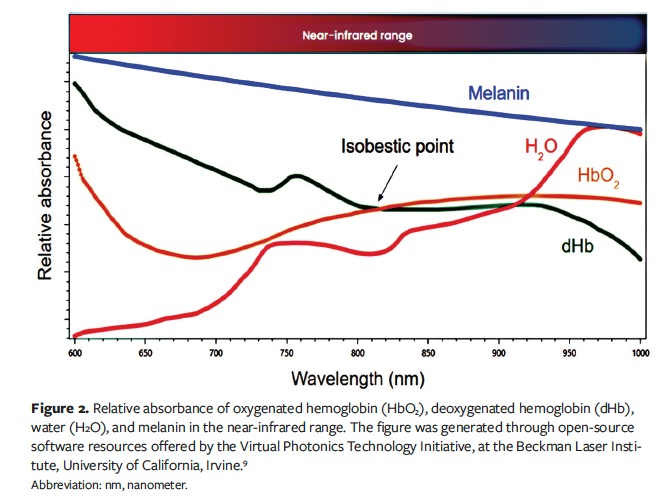

NIRS measures the tissue absorption and scattering of NIR light based on the fundamental principle that wavelength-dependent signal attenuation (absorption) in an object (eg, skin) is directly proportional to the concentration of chromophores. Multiple chromophores exist in skin, but the main chromophores of skin at the NIR region are oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO₂), deoxygenated hemoglobin (dHb), water, and melanin. Most NIRS oximetry imaging systems employ at least 2 distinct wavelengths, 1 above and 1 below 810 nm, because 810 nm serves as an isobestic point where the absorption spectra of dHb and HbO₂ intersect (Figure 2).⁹

NIRS: A Historical Perspective

One of the first milestones in the development of NIRS imaging was the introduction of pulse oximetry in the 1970s.10 Pulse oximeters measure peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂), that is, the percentage of oxygen-saturated hemoglobin in the blood, focusing on systemic blood oxygen levels. By employing 2 wavelengths—red (660 nm) and IR (940 nm)—pulse oximeters calculate the proportion of HbO₂ to total hemoglobin (tHb = HbO₂ + dHb) using the Beer-Lambert law. The formula is: SpO₂ = HbO₂ / (HbO₂ + dHb).

Following pulse oximetry, the development of fiber-based NIRS technologies enabled measurements of tissue oxygen saturation (StO₂) directly beneath the optical fibers, providing a localized assessment of microcirculation oxygenation. Unlike the pulse oximeter’s systemic approach, fiber-based NIRS technologies focus on

local tissue health and perfusion. Fiber-based NIRS measures StO₂ by detecting the absorbance of NIR light by HbO₂ and dHb using the same formula but represented as: StO₂ = HbO₂ / (HbO₂ + dHb).

Modern Solutions: Hyperspectral Imaging, Multispectral Imaging, and Spatial Frequency Domain Imaging

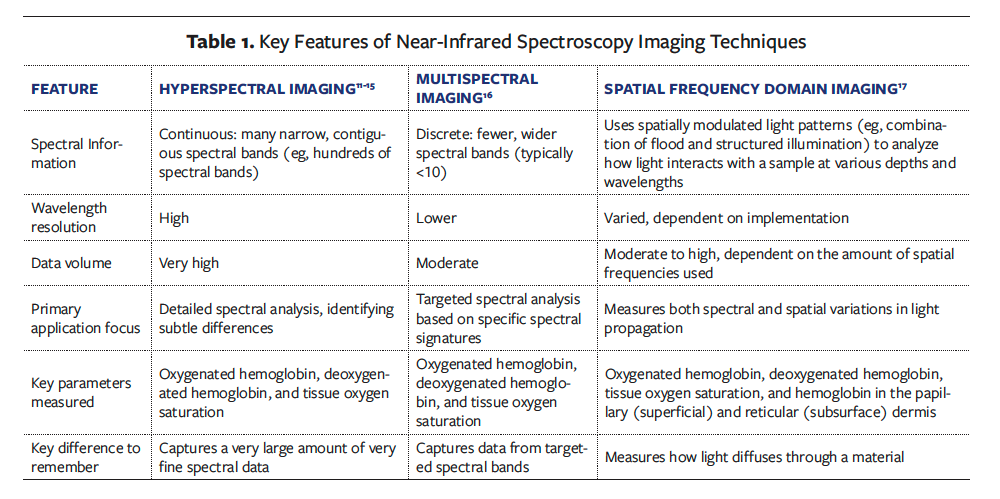

Building on the legacy of pulse oximetry and fiber-based NIRS, modern NIRS imaging techniques enable noncontact, real-time microcirculation imaging over larger tissue areas while retaining the foundational principle of measuring StO₂ through hemoglobin NIR absorbance. Among the most notable NIRS imaging techniques are hyperspectral imaging,11-15 multispectral imaging,16 and spatial frequency domain imaging,17 each with unique features and distinct practical and methodological considerations.

What is common among these techniques is that they all use wavelengths in the visible and/or NIR regions to obtain 2-dimensional maps of StO₂ in the wound bed and surrounding tissue. Table 1 lists key features of these techniques.

Examples of NIRS Imaging Systems Used in Wound Care

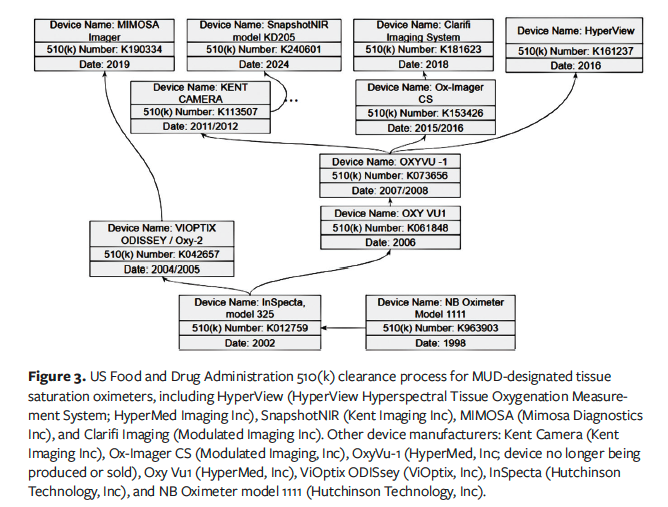

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies devices using a rules-based approach. For example, 21 CFR Part 870.2700 applies to oximeters, with the product code MUD designated for tissue saturation oximeters.18 These devices are risk designated Class II, requiring premarket notification, a 510(k) submission. According to FDA identification (§ 870.2700), an oximeter is a device that transmits radiation at specific wavelengths to measure oxygen saturation based on the amount of reflected or scattered radiation.19

The FDA 510(k) premarket submission process requires submitters to demonstrate that the device is as safe and effective as—meaning substantially equivalent to—a legally marketed predicate device. Figure 3 illustrates the regulatory pathways and predicate devices for several MUD-designated tissue saturation oximeters, including HyperView Hyperspectral Tissue Oxygenation Measurement System (HyperMed Imaging, Inc), SnapshotNIR (Kent Imaging Inc), MIMOSA Imager (Mimosa Diagnostics Inc), and Clarifi Imaging (Modulated Imaging Inc [dba Modulim]).

Typically, NIRS devices emit light at wavelengths ranging from approximately 600 nm to 1000 nm, though this range is not standardized. For all of these devices, as part of FDA clearance, publicly available information typically includes the specific wavelengths (or wavelength range) used. For example, devices may specify individual wavelengths such as 620 nm, 630 nm, 700 nm, 810 nm, 880 nm, and 980 nm, or may provide a range, such as 6 wavelengths between 600 nm and 1000 nm. In NIRS, wavelengths and their specific values are reported because they directly relate to the absorbance and reflectance properties of biological tissues, corresponding to key absorption bands.

Key Measurable Parameters

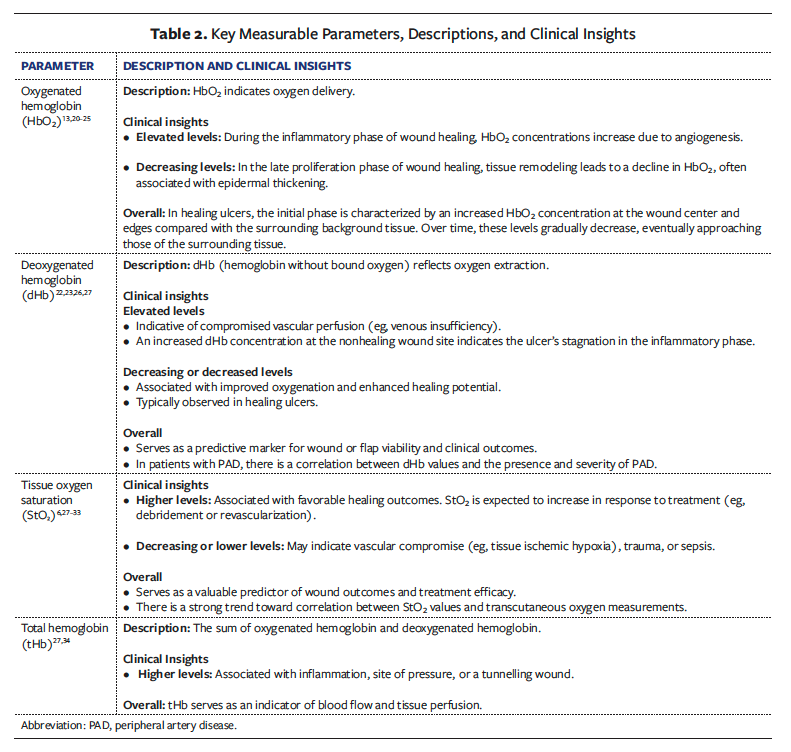

The primary parameters assessed via NIRS include HbO₂, dHb, StO₂, and tHb (Table 2).

Some NIRS imaging systems report HbO₂, dHb, and tHb, and a few can report healing index or some other metrics, but all MUD products must report StO₂. This standardized focus on a single, easily interpretable metric simplifies clinical assessments and supports quicker decision-making.

NIRS Measurements to Predict Wound Healing

Percentage area reduction (PAR) and percentage volume reduction measurements are known clinical end points, with the 4-week PAR serving as a prognostic indicator for evaluating the efficacy of treatments.35-38

While NIRS is not used to measure PAR, it can provide complementary circulatory information that, when integrated with PAR, offers a more comprehensive view of wound healing dynamics. For example, Kounas et al24 evaluated the ability of HbO₂ levels to predict diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) healing in a cohort of 27 patients and observed an inverse correlation between HbO₂ and the percentage of ulcer size reduction.

Longobardi et al39 conducted a single-

center randomized controlled trial involving 81 adults (aged ≥18 years) with hard-to-heal venous leg ulcers (VLUs). The study evaluated simultaneous measurements of StO₂ and wound dimensions to predict the healing trajectory under protocols using conventional treatment alone or in combination with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The findings concluded that NIRS analysis of StO₂ and wound area is effective in predicting the healing course of VLUs.

Clinical Applications of NIRS in Wound Care

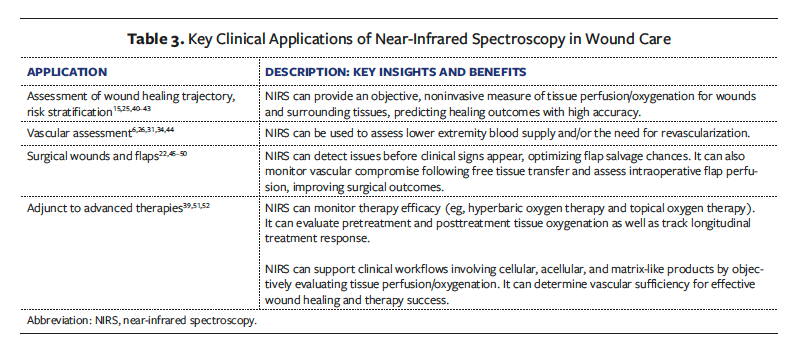

NIRS imaging offers real-time, objective data on tissue oxygenation and perfusion, making it particularly useful for monitoring wounds of varying etiologies and assessing the efficacy of various treatment modalities. Table 3 provides examples of clinical applications of NIRS in wound care.

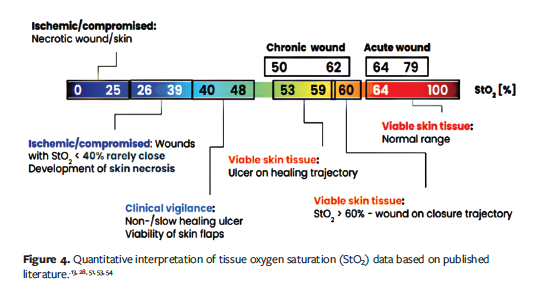

Quantitative Interpretation of StO₂

Studies show that higher StO₂ levels are associated with better healing potential (Figure 4). Landsman53 found that wounds with an average StO₂ level below 40% across the wound bed rarely achieved closure. Nouvong et al13 reported that the mean (SD) StO₂ measured from the dorsal foot was 53% (13%) in DFUs that healed, compared with 47% (12%) in those that did not heal. Similarly, Philimon et al28 found that acute wounds had a mean (SD) StO₂ of 71.38% (7.07%), while chronic wounds had significantly lower levels (56.48% [6.27%]) (P < .05), indicating that chronic wounds, which tend to heal more slowly or fail to heal, are characterized by lower oxygenation. In healthy individuals, Suludere et al54 found that mean StO₂ levels ranged from 64% to 73% on the dorsal foot and from 63% to 72% on the plantar foot, providing a baseline for normal tissue oxygenation. Arnold and Marmolejo55 educated clinicians on the proper interpretation of point-of-care NIRS imaging in daily wound care practice.

NIRS tissue oxygenation images are typically displayed using a jet color map, in which blue indicates low oxygenation and red signifies high oxygenation. As shown in Figure 4, the gradient transitions from blue/green (low) to yellow (mid-range) to orange/red (high).

Significant increases in oxygen saturation during the early stages of treatment are also strongly linked to positive response to treatment and improved healing outcomes. In a series of 5 patients with nonhealing wounds, Cole and Woodmansey51 observed that wounds with a greater than 10% increase in StO₂ within the first week of starting treatment achieved complete healing by 3 to 5 weeks. In contrast, wounds with a smaller increase of 3% to 7% StO₂ within the first week did not heal within 5 weeks.

Challenges in NIRS Imaging

NIRS is based on the principles of light-based imaging, and all light-based imaging techniques are susceptible to various light-related artifacts. One such challenge is the effect of skin tone on imaging results. While NIRS imaging is expected to reliably extract physiological parameters for lighter skin tones (Fitzpatrick skin types I-IV),56 the high absorption of NIR light by melanin in darker skin can distort NIRS readings.57,58 In skin with high melanin content, increased absorption of NIR light occurs, reducing the amount of light that penetrates deeper tissues and is reflected back to the sensors. This elevated absorption can result in artificially lower tissue oxygenation measurements. Algorithms can improve NIRS measurements across all skin tones by labeling different skin tones to enable melanin correction in tissue oxygenation maps.54,59-61 The most common methods for accounting for melanin absorbance include the use of a melanin index, with which the relevant portion of the spectrum is used to estimate melanin content and a corrective factor applied accordingly.57 Alternative approaches rely on image-based analysis combined with deep learning or machine learning algorithms to classify skin tone. Whatever approach is used, NIRS devices should be validated across diverse skin tones to confirm that their correction strategies are effective.

Other artifacts arise from motion, whether from the subject or the equipment, introducing unwanted noise or distortions in the spectral data. Movement-related artifacts affect all imaging systems to some degree, prompting the development of advanced mitigation strategies such as motion detection algorithms and post-processing techniques.

Another group of artifacts arises from geometric factors, such as convex curved surfaces with different depth planes, leading to inaccurate tissue oxygenation measurements on curved or angled surfaces. Curvature correction models have been recently developed to address this issue.62 However, the challenge remains that commercial systems rarely disclose the specifics of the techniques and algorithms they use.

A practical way to mitigate the influence of artifacts (eg, melanin) in real-world applications is to use relative comparisons. This may involve tracking changes over time, such as before and after a procedure (eg, debridement) or between clinic visits, or assessing responses to physiological challenges, such as provocative maneuvers.44 Anatomical comparisons may also be used, such as contrasting the affected area with the contralateral side (eg, left leg vs right leg) or with adjacent healthy tissue, or by applying site-specific indices such as the plantar-palmar index.63

Artifacts caused by motion or geometric factors cannot typically be corrected by the end user in practical settings. However, they are often visually distinctive, allowing users to recognize and address them by simply retaking the image. This underscores the importance of proper training and the user learning curve in acquiring reliable images.

The FDA 2025 draft guidance document titled “Pulse Oximeters for Medical Purposes: Non-Clinical and Clinical Performance Testing, Labeling, and Premarket Submission Recommendations” provides recommendations for nonclinical and clinical performance testing to support premarket submissions for pulse oximeters intended for medical purposes.64 However, the draft guidance does not address oximeters under the product code MUD. The authors of the present review believe there is a need for greater standardization in this area. Standardized performance information from manufacturers would benefit both clinicians and payors.

Future Directions

NIRS imaging is emerging as a valuable tool in advancing wound care, with significant potential for future development. A major innovation on the horizon is integrating artificial intelligence (AI) with advanced medical imaging to create predictive wound healing models as a decision support tool.65-67 Combination of NIRS and AI offers clinicians real-time insights into healing potential, enabling faster and more accurate treatment decisions.68

Innovative spatiotemporal NIRS-based approaches, which are capable of mapping oxygenation flow patterns over time and space, hold promise for a deeper understanding of wound dynamics.69 Spatiotemporal NIR-based imaging methods can map oxygenation flow patterns around DFUs, identifying areas in need of urgent care.

The miniaturization of NIRS technology into smartphone-based imaging devices for point-of-care applications represents another exciting advancement.70-72 Such portable systems could bring real-time monitoring to bedside care, improving accessibility and efficiency, especially in underserved or remote settings. Furthermore, combining NIRS imaging with other diagnostic methods, such as thermal or fluorescence imaging, can enhance wound healing monitoring. For example, smartphone thermography has been used to assess wound healing in second-degree burns by detecting improved blood flow to the burn site, demonstrating high validity in evaluating both healing potential and progression.73 In another study, tissue oxygenation and thermal maps were used together to assess the healing status of DFUs.70 This integrated approach allowed for the differentiation between healing and nonhealing DFUs by providing complementary physiological data.

An interesting future direction for NIRS could be its application in the early detection, prevention, or treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries. Wywialowski74 highlighted tissue perfusion as a key underlying factor in the development and treatment of pressure ulcers. Andersen et al75 conducted a study involving 15 patients (16 wounds), including 3 pressure injuries, using serial imaging to track wound changes over time. Wahab and Lapucha40 discussed the clinical applications of NIRS in chronic pressure injuries, demonstrating that NIRS is a valuable adjunct for wound diagnosis and for selecting the appropriate advanced treatment modality. Bates-

Jensen et al76 and Wyss et al77 investigated the effects of external pressure on tissue oxygenation.

The wound biome, comprising the microbiome and its biochemical interactions, is also critical to advancing chronic wound management.78 NIRS imaging can complement biochemical analysis by providing real-time, noninvasive data on tissue oxygenation and perfusion, contextualizing microbial and metabolic activity. Emerging research also suggests that NIRS could theoretically identify microbes via spectral signatures, potentially enabling a single system to assess physiological and microbial traits.79 Integrating NIRS-derived StO₂ with proteomic or metabolomic profiling can yield a holistic view of wound healing, enhancing diagnostic precision and personalized treatment.

Although several NIRS imaging systems are available on the US market, detailed pricing information is rarely publicly disclosed. Predicate devices such as T.Ox (ViOptix Inc) have been reported to cost around $25 000, with additional per-use expenses of approximately $1450 for disposable probes.80 In contrast, modern NIRS imaging systems are designed without the need for disposable components,46 eliminating ongoing consumable costs and potentially reducing overall long-term expenditures. Looking ahead, cost optimization remains an important factor for enabling future broader adoption of NIRS imaging in both clinical and research settings.

As NIRS technology advances, it is poised to play an even more integral role in early detection, monitoring, and guiding treatment decisions, thus significantly enhancing care pathways for those at risk of chronic wounds. Thus, the authors of the current review, as participating members of the FDA-approved WCCC TWG, will follow up this review with surveys to manufacturers of MUD FDA-listed devices used by wound practitioners to further elucidate their capabilities for use in research and clinical practice, as well as other adoption-related metrics.

Limitations

This literature review of NIRS imaging in chronic wound care is limited by its reliance on published sources, which may not fully reflect the most recent technological advancements or unpublished methodologies. To help address these gaps, the authors of this review are conducting follow-up surveys with manufacturers of FDA-listed MUD devices to further clarify system capabilities. Additionally, the nonsystemic nature of this review presents inherent limitations. Its primary focus is on describing NIRS modalities, measurement parameters, and clinical applications, and it lacks the level of critical appraisal found in systematic reviews.

Conclusion

This comprehensive review underscores the value of integrating NIRS imaging into routine clinical practice, with NIRS imaging offering noninvasive, real-time evaluation of tissue oxygenation and perfusion. By combining traditional wound assessment metrics, such as PAR, with the advanced capabilities of NIRS real-time imaging, health care providers can personalize care using enhanced diagnostic accuracy, optimized treatment strategies, and patient engagement to ultimately improve patient outcomes. As the prevalence of chronic wounds continues to rise, the adoption of innovative tools like NIRS imaging will play an essential role in addressing this growing public health burden.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Alisha Oropallo, MD1-4; Alex G. Ortega-Loayza, MD, MCR4,5; Holly Korzendorfer, PT, PhD, CWS4,6; Francis James, BFA4,7; Peggy Dotson, RN, BS4; Anna Khimchenko, PhD4,8; Vickie R. Driver, DPM, MS4,9; and Sharon Eve Sonenblum, PhD4,10

Affiliations: 1Department of Vascular Surgery, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine, Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, NY, USA; 2Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY, USA; 3Comprehensive Wound Healing Center, Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Northwell Health, Lake Success, NY, USA; 4Wound Care Collaborative Community, Orlando, FL, USA; 5Department of Dermatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA; 6Doctor of Physical Therapy Program, Marist University, Poughkeepsie, NY, USA; 7TRUE-See, New Orleans, LA, USA; 8MIMOSA Diagnostics Inc, Toronto, ON, Canada; 9Washington State University Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine, Spokane, WA, USA; 10Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

Disclosure: A.G.O-L. is the Past President of the Pacific Dermatology Association and serves as an associate editor for Dermatology (Karger) and as an editorial board member of the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. In addition, he is a consultant for Genentech and Guidepoint and an advisor to Bristol Meyer Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. He has received research grants from Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, and Pfizer. He is supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant R01 AR083110. F.J. is the Founder and Chief Product Officer for TRUE-See Systems. A.K. is a Medical Science Liaison (employee) at MIMOSA Diagnostics. All other authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: Because this is a literature review, no patient data were used; as such, no institutional review board or other ethical approval was required.

Correspondence: Sharon Eve Sonenblum, PhD; Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University, 520 Clifton Rd NE, Atlanta, GA 30322; sharoneve@emory.edu

Manuscript Accepted: August 22, 2025

References

1. Schreml S, Szeimies RM, Prantl L, Karrer S, Landthaler M, Babilas P. Oxygen in acute and chronic wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(2):257-268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09804.x

2. Castilla DM, Liu ZJ, Velazquez OC. Oxygen: implications for wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2012;1(6):225-230. doi:10.1089/wound.2011.0319

3. Aerden D, Massaad D, von Kemp K, et al. The ankle-brachial index and the diabetic foot: a troublesome marriage. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25(6):770-777. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2010.12.025

4. Benitez E, Sumpio BE. Pulse volume recording for peripheral vascular disease diagnosis in diabetes patients. J Vasc Diagn. 2015;3:33–39. doi:10.2147/JVD.S68048

5. Singhania P, Das TC, Bose C, et al. Toe brachial index and not ankle brachial index is appropriate in initial evaluation of peripheral arterial disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2024;16(1):52. doi:10.1186/s13098-024-01291-2

6. Bolakale-Rufai IK, Thompson MR, Concha-

Moore K, et al. Assessment of revascularization impact on microvascular oxygenation and perfusion using spatial frequency domain imaging. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(7):rjad382. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjad382

7. Bosetti F, Galis ZS, Bynoe MS, et al. “Small blood vessels: big health problems?”: scientific recommendations of the National Institutes of Health Workshop. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(11):e004389. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004389

8. Bashkatov AN, Genina EA, Kochubey VI, Tuchin VV. Optical properties of human skin, subcutaneous and mucous tissues in the wavelength range from 400 to 2000 nm. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2005;38(15):2543. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/38/15/004

9. Virtual Photonics Technology Initiative by the Laser Microbeam and Medical Program (LAMMP), an NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center at the Beckman Laser Institute and Medical Clinic. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://virtualphotonics.org/software

10. Tekin K, Karadogan M, Gunaydin S, Kismet K. Everything about pulse oximetry—Part 1: history, principles, advantages, limitations, inaccuracies, cost analysis, the level of knowledge about pulse oximeter among clinicians, and pulse oximetry versus tissue oximetry. J Intensive Care Med. 2023;38(9):775-784. doi:10.1177/08850666231185752

11. Khaodhiar L, Dinh T, Schomacker KT, et al. The use of medical hyperspectral technology to evaluate microcirculatory changes in diabetic foot ulcers and to predict clinical outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):903-910. doi:10.2337/dc06-2209

12. Saiko G, Lombardi P, Au Y, Queen D, Armstrong D, Harding K. Hyperspectral imaging in wound care: a systematic review. Int Wound J. 2020;17(6):1840-1856. doi:10.1111/iwj.13474

13. Nouvong A, Hoogwerf B, Mohler E, Davis B, Tajaddini A, Medenilla E. Evaluation of diabetic foot ulcer healing with hyperspectral imaging of oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):2056-2061. doi:10.2337/dc08-2246

14. Yudovsky D, Nouvong A, Pilon L. Hyperspectral imaging in diabetic foot wound care. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(5):1099-1113. doi:10.1177/193229681000400508

15. González-Villacorta PM, López-Moral M, García-Madrid M, García-Morales E, Tardáguila-

García A, Lázaro-Martínez JL. Hyperspectral imaging in the healing prognosis of diabetes-

related foot ulcers. A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Microcirculation. 2025;32(3):e70005. doi:10.1111/micc.70005

16. Sowa MG. SnapshotNIR: A handheld multispectral imaging system for tissue viability assessment. In: Proceedings of the Joint TC1 - TC2 International Symposium on Photonics and Education in Measurement Science. 2019;11144:111440B.

17. Cuccia DJ. Spatial frequency domain imaging (SFDI): a technology overview and validation of an LED-based clinic friendly device. In: Proceedings of SPIE MOEMS-MEMS. 2012;8254:825405.

18. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Product Classification: Oximeter, tissue saturation (Product Code MUD). Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpcd/classification.cfm?id=MUD

19. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 21 CFR § 870.2700: Oximeter. Accessed September 26, 2025. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-H/part-870/subpart-C/

section-870.2700

20. Weingarten MS, Neidrauer M, Mateo A, et al. Prediction of wound healing in human diabetic foot ulcers by diffuse near-infrared spectroscopy: a pilot study. Wound Repair Regen. 2010;18(2):180-185. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475x.2010.00583.x

21. Yudovsky D, Nouvong A, Schomacker K, Pilon L. Monitoring temporal development and healing of diabetic foot ulceration using hyperspectral imaging. J Biophotonics. 2011;4(7-8):565-576. doi:10.1002/jbio.201000117

22. Nguyen JT, Lin SJ, Tobias AM, et al. A novel pilot study using spatial frequency domain imaging to assess oxygenation of perforator flaps during reconstructive breast surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;71(3):308-315. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e31828b02fb

23. Chin JA, Wang EC, Kibbe MR. Evaluation of hyperspectral technology for assessing the presence and severity of peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(6):1679-1688. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2011.06.022

24. Kounas K, Dinh T, Riemer K, Rosenblum BI, Veves A, Giurini JM. Use of hyperspectral imaging to predict healing of diabetic foot ulceration. Wound Repair Regen. 2023;31(2):199-204. doi:10.1111/wrr.13071

25. Kwasinski R, Fernandez C, Leiva K, et al. Tissue oxygenation changes to assess healing in venous leg ulcers using near-infrared optical imaging. Adv Wound Care. 2019;8(11):565-579. doi:10.1089/wound.2018.0880

26. van Schilt KLJ, Hollander EF, Koelemay MJ, van Geloven AAW, Olthof DC. Assessment of microcirculatory changes in local tissue oxygenation after revascularization for peripheral arterial disease with the Hyperview®, a portable hyperspectral imaging device. Vascular. 2023;31(5):961-967. doi:10.1177/17085381221102813

27. Serena T, Tettelbach WH, Rader A, et al. An advanced diagnostic imaging tool to enhance clinical decision-making and wound healing. J Wound Care. 2025;34(4):272-277. doi:10.12968/jowc.2025.0104.

28. Philimon SP, Huong AKC, Ngu XTI. Tissue oxygen level in acute and chronic wound: a comparison study. Jurnal Teknologi. 2020;82(4):131-140. doi:10.11113/jt.v82.14418

29. Cole WE, Coe S, Maislin G, Marmolejo VL. A non-invasive focused extracorporeal shock wave therapy system promotes increased tissue oxygen saturation in chronic wounds in persons with diabetes. Am J Nurs Sci. 2021;10(3):166. doi:10.11648/j.ajns.20211003.14

30. Serena TE, Yaakov R, Serena L, Mayhugh T, Harrell K. Comparing near infrared spectroscopy and transcutaneous oxygen measurement in hard-to-heal wounds: a pilot study. J Wound Care. 2020;29(Sup6):S4–S9. doi:10.12968/jowc.2020.29.Sup6.S4

31. Weinkauf C, Mazhar A, Vaishnav K, Hamadani AA, Cuccia DJ, Armstrong DG. Near-instant noninvasive optical imaging of tissue perfusion for vascular assessment. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(2):555–562. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2018.06.202

32. Bowen RE, Treadwell G, Goodwin M. Correlation of near infrared spectroscopy measurements of tissue oxygen saturation with transcutaneous pO2 in patients with chronic wounds. SM Vasc Med. 2016;1(2):1006.

33. Jafari-Saraf L, Wilson SE, Gordon IL. Hyperspectral image measurements of skin hemoglobin compared with transcutaneous PO2 measurements. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26(4):537–548. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2011.12.002

34. Mazhar A, D’Huyvetter K, Murphy GA, Jett S, Cuccia DJ, Armstrong DG. Noninvasive mapping of hemoglobin microcirculation using spatial frequency domain imaging in patients with history of limb complications who have undergone revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(1):E67.

35. Serena T, Yaakov S, Yaakov R, King E, Driver VR. Percentage area reduction at week 4 as a prognostic indicator of complete healing in patients treated with standard of care: a post hoc analysis. J Wound Care. 2024;33(Sup9):S36–S42. doi:10.12968/jowc.2024.0141

36. Bull RH, Staines KL, Collarte AJ, Bain DS, Ivins NM, Harding KG. Measuring progress to healing: a challenge and an opportunity. Int Wound J. 2022;19(4):734–740. doi:10.1111/iwj.13669

37. Driver VR, Gould LJ, Dotson P, Allen LL, Carter MJ, Bolton LL. Evidence supporting wound care end points relevant to clinical practice and patients’ lives. Part 2. Literature survey. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27(1):80–89. doi:10.1111/wrr.12676

38. Gwilym BL, Mazumdar E, Naik G, Tolley T, Harding K, Bosanquet DC. Initial reduction in ulcer size as a prognostic indicator for complete wound healing: a systematic review of diabetic foot and venous leg ulcers. Adv Wound Care. 2023;12(6):327–338. doi:10.1089/wound.2021.0203

39. Longobardi P, Hartwig V, Santarella L, et al. Potential markers of healing from near infrared spectroscopy imaging of venous leg ulcer: a randomized controlled clinical trial comparing conventional with hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Wound Repair Regen. 2020;28(6):856–866. doi:10.1111/wrr.12853

40. Wahab N, Lapucha MA. Clinical applications of near-infrared spectroscopy in the modern wound care clinic. Today’s Wound Clinic [Internet]; 2021. Accessed March 25, 2025. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/twc/articles/clinical-applications-near-infrared-spectroscopy-modern-wound-care-clinic

41. Lei J, Rodriguez S, Jayachandran M, et al. Assessing the healing of venous leg ulcers using a noncontact near-infrared optical imaging approach. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2018;7(4):134-143. doi:10.1089/wound.2017.0745

42. Wang S, Gu M, Zhang M, Tan X. Research on a burn severity detection method based on hyperspectral imaging. Sensors. 2025;25(5):1330. doi:10.3390/s25051330

43. Wild T, Marotz J, Aljowder A, Siemers F. Burn wound dynamics measured with hyperspectral imaging. Eur Burn J. 2025;6(1):7. doi:10.3390/ebj6010007

44. Reiter HJ, Andersen CA. Near-infrared spectroscopy with a provocative maneuver to detect the presence of severe peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2023;10(6):101379. doi:10.1016/j.jvscit.2023.101379

45. Chen Y, Shen Z, Shao Z, Yu P, Wu J. Free flap monitoring using near-infrared spectroscopy: a systemic review. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76(5):590–597. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000000430

46. Hill WF, Kinaschuk K, Temple-Oberle C. Intraoperative near-infrared spectroscopy can predict skin flap necrosis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12(3):e5669. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000005669

47. Newton E, Butskiy O, Shadgan B, Prisman E, Anderson DW. Outcomes of free flap reconstructions with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) monitoring: a systematic review. Microsurgery. 2020;40(2):268–275. doi:10.1002/micr.30526

48. Lindelauf AAMA, Saelmans AG, van Kuijk SMJ, van der Hulst RRWJ, Schols RM. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) versus hyperspectral imaging (HSI) to detect flap failure in reconstructive surgery: a systematic review. Life (Basel). 2022;12(1):65. doi:10.3390/life12010065

49. Moritz WR, Daines J, Christensen JM, Myckatyn T, Sacks JM, Westman AM. Point-of-care tissue oxygenation assessment with SnapshotNIR for alloplastic and autologous breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11(7):e5113. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000005113

50. Kagaya Y, Miyamoto S. A systematic review of near-infrared spectroscopy in flap monitoring: current basic and clinical evidence and prospects. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71(2):246–257. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2017.10.020

51. Cole W, Woodmansey E. Monitoring the effect of continuous topical oxygen therapy with near-infrared spectroscopy: a pilot case series in wound healing. Wounds. 2024;36(5):154–159. doi:10.25270/wnds/23150

52. Wu S, Carter M, Cole W, et al. Best practice for wound repair and regeneration use of cellular, acellular and matrix-like products (CAMPs). J Wound Care. 2023;32(Sup4b):S1–S31. doi:10.12968/jowc.2023.32.Sup4b.S1

53. Landsman A. Visualization of wound healing progression with near infrared spectroscopy: a retrospective study. Wounds. 2020;32(10):265–271.

54. Suludere MA, Tarricone A, Najafi B, et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy data for foot skin oxygen saturation in healthy subjects. Int Wound J. 2024;21(3):e14814. doi:10.1111/iwj.14814

55. Arnold J, Marmolejo VL. Interpretation of near-infrared imaging in acute and chronic wound care. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(5):778. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11050778

56. Saiko G, Bartlett RL, Ramírez-GarcíaLuna JL. Optical Methods for Managing the Diabetic Foot. CRC Press; 2024.

57. Matas A, Sowa M, Taylor G, Mantsch HH. Melanin as a confounding factor in near infrared spectroscopy of skin. Vibrational Spectroscopy. 2002;28(1). doi:10.1016/S0924-2031(01)00144-8

58. Couch L, Roskosky M, Freedman BA, Shuler MS. Effect of skin pigmentation on near infrared spectroscopy. Am J Analyt Chem. 2015;6(12):911–916. doi:10.4236/ajac.2015.612086

59. Kaile K, Sobhan M, Mondal A, Godavarty A. Machine learning algorithms to classify Fitzpatrick skin types during tissue oxygenation mapping. In: Proceedings of the Biophotonics Congress:

Biomedical Optics 2022 (Translational, Microscopy, OCT, OTS, BRAIN). Optica Publishing Group; 2022. doi:10.1364/TRANSLATIONAL.2022.JM3A.4

60. Leizaola D, Vedere N, Sinclair S, et al. Skin color classification by deep learning and traditional thresholding techniques during NIR imaging. In: Proceedings of the Optica Biophotonics Congress: Biomedical Optics 2024 (Translational, Microscopy, OCT, OTS, BRAIN). Optica Publishing Group; 2024. doi:10.1364/OTS.2024.OW3D.5

61. Leizaola D, Sobhan M, Kaile K, Mondal AM,

Godavarty A. Deep learning algorithms to classify Fitzpatrick skin types for smartphone-based NIRS imaging device (Erratum). Proceedings of the SPIE. 2024; 12516:1251612.

62. Roy HS, Policard CP, Godavarty A. Curvature correction in near-infrared spectroscopy for diabetic foot ulcers: a phantom study. In: Proceedings of Optical Diagnostics and Sensing XXV: Toward Point-of-Care Diagnostics Volume 13316. 2025;133160C. doi:10.1117/12.3042595

63. Niezgoda JA, Das D, Nayem Pinky N, et al. The plantar-palmar index with near infrared spectroscopy as an alternative to the ankle-brachial index for non-invasive evaluation of vascular perfusion and peripheral arterial disease. Int J Tissue Repair. 2025;1(1). doi:10.63676/m0ww6304

64. Center for Devices & Radiological Health. Pulse oximeters for medical purposes - non-clinical and clinical performance testing, labeling, and premarket submission recommendations. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2025. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/pulse-oximeters-medical-purposes-non-clinical-and-clinical-performance-testing-labeling-and

65. Rangaiah PKB, Kumar BPP, Huss F, Augustine R. Precision diagnosis of burn injuries using imaging and predictive modeling for clinical applications. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):7604.

66. Rathore PS, Kumar A, Nandal A, Dhaka A, Sharma AK. A feature explainability-based deep learning technique for diabetic foot ulcer identification. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):6758.

67. Almufadi FN, Alhasson F, Alharbi S. E-DFu-Net: an efficient deep convolutional neural network models for Diabetic Foot Ulcer classification. Biomol Biomed. 2025;25(2):445–460. doi:10.17305/bb.2024.11117

68. Squiers JJ, Thatcher JE, Bastawros DS, et al. Machine learning analysis of multispectral imaging and clinical risk factors to predict amputation wound healing. J Vasc Surg. 2022;75(1):279–285. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2021.06.478

69. Leiva K, Leizaola D, Gonzalez I, et al. Spatial-temporal oxygenation mapping using a near-infrared optical scanner: towards peripheral vascular imaging. Ann Biomed Eng. 2023;51(9):2035–2047. doi:10.1007/s10439-023-03229-7

70. Chiwo FS, Leizaola D, Kaile K, et al. Combining tissue oxygenation and thermal maps to monitor healing status of diabetic foot ulcers using smartphone-based imaging devices. In: Proceedings of the Optica Biophotonics Congress: Biomedical Optics 2024 (Translational, Microscopy, OCT, OTS, BRAIN). Optica Publishing Group; 2024. doi:10.1364/TRANSLATIONAL.2024.TS1B.4

71. Leizaola D, Kaile K, Hernandez M, et al. Tissue oxygenation changes with debridement in DFUs using a smartphone-based NIRS imaging device. In: Proceedings of the Optica Biophotonics Congress: Biomedical Optics 2024 (Translational, Microscopy, OCT, OTS, BRAIN). Optica Publishing Group, 2024. doi:10.1364/TRANSLATIONAL.2024.TM1B.4

72. Rickards T, Roberts C, Smith T, Shittu S, Boodoo C, Cross K. Using near-infrared spectroscopy and education to support older adults with diabetic foot ulcers to age-in-place: a case series. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2024;37(8):422-428. doi:10.1097/ASW.0000000000000146

73. Madian IM, Sherif WI, El Fahar MH, Othman WN. The use of smartphone thermography to evaluate wound healing in second-degree burns. Burns. 2025;51(3):107307. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2024.107307

74. Wywialowski EF. Tissue perfusion as a key underlying concept of pressure ulcer development and treatment. J Vasc Nurs. 1999;17(1):12-16. doi:10.1016/s1062-0303(99)90003-1

75. Andersen C, Reiter HJ, Marmolejo VL. Redefining wound healing using near-infrared spectroscopy. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2024;37(5):243-247. doi:10.1097/ASW.0000000000000115

76. Bates-Jensen BM, Jordan K, Jewell W, Sonenblum

SE. Thermal measurement of erythema across skin tones: implications for clinical identification of early pressure injury. J Tissue Viability. 2024;33(4):745-752. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2024.08.002

77. Wyss JK, Ghazi L, Madden JDW, Shadgan B. Using near-infrared spectroscopy to investigate the effects of externally applied pressure on soft tissue oxygenation for pressure injury prevention. Poster presented at: 2022 UBC SBME Research Day; June 2022.

78. Uberoi A, McCready-Vangi A, Grice EA. The wound microbiota: microbial mechanisms of impaired wound healing and infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2024;22:507-521.

79. Yin M, Li J, Huang L, et al. Identification of microbes in wounds using near-infrared spectroscopy. Burns. 2022;48(4):791-798. doi:10.1016/

j.burns.2021.09.002

80. Berthelot M, Ashcroft J, Boshier P, et al. Use of near-infrared spectroscopy and implantable Doppler for postoperative monitoring of free tissue transfer for breast reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7(10):e2437. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002437