Assessing the Knowledge of Patients With Diabetes About Foot Care and Prevention of Foot Complications in Cameroon, West Africa

©2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. As the incidence of diabetes continues to rise throughout the world, including Africa, diabetic foot complications are a significant factor in morbidity, hospital length of stay, and health care costs. An emphasis on prevention through patient education may reverse this trend. Objective. To survey patients with diabetes in Cameroon, West Africa, to assess their knowledge about foot care and prevention of complications, with the goal of improving diabetic foot education across a hospital system. Methods. The sample included 130 patients with diabetes at 2 hospitals within the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services. Participants were seen in outpatient clinics or as inpatients. Nurses trained in wound care conducted the study between December 23, 2021, and August 26, 2022. Investigators administered an examiner-designed oral survey to collect foot care knowledge and disease-related data and performed a standard diabetic foot examination to assess for evidence of sensory, motor, or autonomic neuropathy. Participants were assigned a risk category based on the history and examination results. Afterward, each participant was taught about diabetic foot care. Results. An oral survey found that patients knew little about foot care or its role in preventing foot complications. Using the International Diabetes Federation risk categorization for diabetic foot complications, 81% of the participants were found to be at high risk or very high risk for foot ulceration and amputation. Conclusion. These findings demonstrate the need for improved teaching on self-care of the feet and personal measures to prevent wounds and amputations during education of patients with diabetes and at sites where patients with diabetes encounter the health care system.

Abbreviations: CBCHS, Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; IDF, International Diabetes Federation; SD, standard deviation.

Background

The global prevalence of diabetes continues to rise. A 2021 report estimated that 463 million people worldwide had diabetes at that time and projected an increase to 578 million by 2030 and to 700 million by 2045.1,2

While diabetes and its complications remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, the situation in Africa is staggering. The IDF estimates that Africa will have the highest increase in the number of people with diabetes among all regions by 2045, at 129%. The proportion of those with undiagnosed diabetes is also highest in the Africa region, at 53.6%.3 Diabetes and the ensuing complications burden health services in many African countries, where resources are often in short supply.4 Among the poorer countries in Africa, foot complications are the leading cause of increased hospital stays for patients with diabetes. These complications are associated with significant mortality, constituting a major public health problem.5

As defined by the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot, the diabetic foot is “infection, ulceration, or destruction of tissues of the foot of a person with currently or previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus, usually accompanied by neuropathy and/or peripheral arterial disease in the lower extremity.”6 Prior studies have shown that peripheral neuropathy frequently leads to diabetic foot ulcers and their complications.7 Researchers estimate that “comprehensive diabetic foot assessments and foot care, based on prevention, education, and a multidisciplinary team approach, may reduce foot complications and amputations by up to 85%.”8

A significant challenge for many countries in Africa is the implementation of educational and follow-up programs that could improve the outcomes of diabetic foot complications. With insufficient numbers of trained medical personnel and facilities, most of sub-Saharan Africa lacks the diabetic foot management model that is standard in Europe and North America.9 Without education on diabetic foot care, patients often ignore early lesions, try unsuccessful home therapy, or go to traditional healers, leading to late presentations and an increased likelihood of complications.8

Due to limited resources, health care for individuals with diabetes in Cameroon has focused primarily on management of the disease rather than prevention. Prevention and early intervention, however, are the keys to minimizing the complications that lead to amputation.10,11 It is motivation and action by the patients with diabetes themselves that will lead to better outcomes.12 In a 2016 article titled “Diabetic Foot: An African Perspective,” Abbas10 wrote, “education remains the most powerful preventive tool in underdeveloped countries, and should be an integral part of prevention programs, and be simple and repetitive.”

The CBCHS encompasses 15 hospitals and 27 satellite clinics in 8 of Cameroon’s 10 regions. This system provides access to monthly diabetes clinics with regular education regarding medication, nutrition, exercise, and self-monitoring. Most hospitals and large clinics offer some foot care education. As of this writing, the CBCHS has 30 nurses working in 15 facilities who have completed a 1-year training program in evidence-based wound care. The investigators of the current study felt that the hospital system afforded a unique opportunity to provide more effective education to patients with diabetes who are at risk of foot complications. The investigators felt that the first step was to survey patients for more information on their own knowledge about caring for their feet and preventing complications.

Methods

Overall study design

An investigator-developed survey was administered orally to those who consented to participate, followed by a standard diabetic foot examination, which included a monofilament test. The patient and family, if present, were then taught about diabetic foot care.

Sample and setting

The study included patients previously diagnosed with diabetes who were seen by wound care nurses at Mbingo Baptist Hospital, a 300-bed teaching and referral hospital in a rural setting in the Belo subdivision of the North West region, and Bafoussam Baptist Hospital, a 102-bed hospital located in Bafoussam, a city of 1.8 million people, in the West region of Cameroon, West Africa. Using a convenience sampling method, participants were recruited from among patients with diabetes who were seen in the outpatient wound clinics, in outpatient diabetes clinics, or as inpatients.

All participants were 21 years of age or older with a diagnosis of diabetes and were able to communicate orally with the investigator. In Cameroon, patients and staff speak multiple languages fluently. Though the written explanation of the study and its purposes and the consent form were in English, the questionnaire and examination questions were administered orally. Language was not a barrier if the investigator could communicate in the language spoken by the participant. Participants were excluded if they were younger than 21 years of age, cognitively impaired, unable to communicate verbally, or employed by the CBCHS.

The investigators explained the purpose of the study and the planned procedures to the prospective participants and invited them to ask questions before signing a written consent form. Afterward, the survey was administered orally, and a diabetic foot examination was performed. Following the examination, the nurse investigators taught the patient and family, if present, about diabetic foot care.

The data were collected between December 23, 2021, and August 26, 2022.

Ethical acknowledgment

Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board Institutional Review Board (IRB#2021-72) on December 20, 2021.

Instruments

Each of the investigators was a wound care nurse. For this study, they developed a nonvalidated knowledge assessment survey. The investigators read the questions to the participants and recorded their answers. The only demographic data collected were the participants’ age and sex.

The knowledge assessment included questions about each patient’s diabetes history, including how long ago the patient had been diagnosed with diabetes, whether they had ever had a foot examination by a nurse or doctor, whether they had been informed about diabetic foot care, and whether they checked their feet at home, and if so, how often. The investigators asked the patients if they had ever had a lower extremity wound, not specifically a foot wound, and, if so, how it started, how long they waited before consulting, where the consultation took place, and how long they received care. The investigators asked if patients had had an amputation and, if so, what was the cause.

The criteria for admission to this study was having diabetes. A lower extremity wound for a patient with diabetes is still a diabetic wound, and the presence of diabetes affects wound healing. The investigators asked patients to list what foot problems would cause them to consult, what they knew about preventive measures for foot complications, whether they attended a diabetes clinic, and, if so, where.

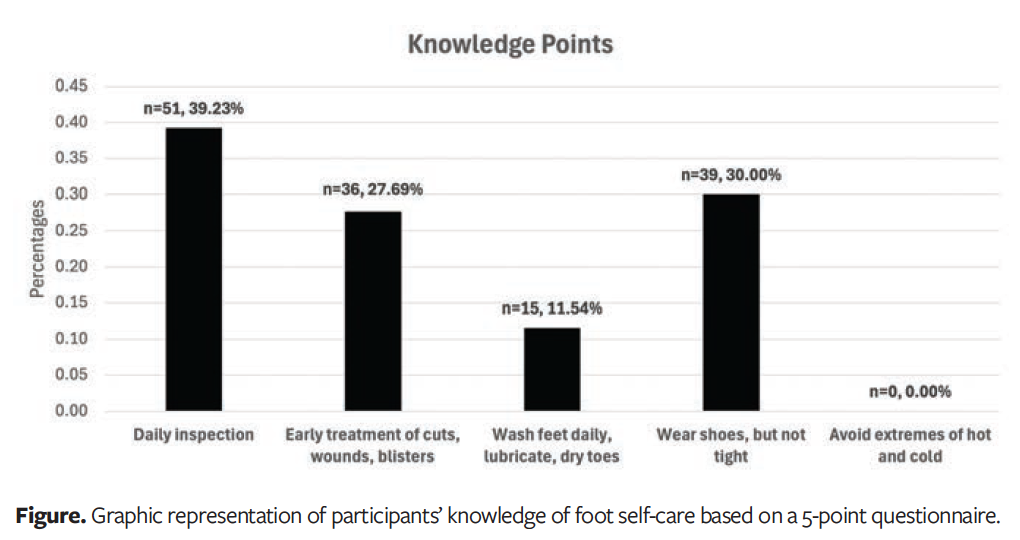

The 5 responses sought from patients related to preventive care of their feet were as follows: (1) check feet daily for any cuts, wounds, callus, or blisters; (2) consult early for any of the aforementioned findings; (3) clean feet daily, but do not soak in water, and dry between toes and lubricate, except between toes; (4) always wear shoes, but not shoes that are too tight; and (5) avoid extremes of hot or cold. Participant responses were then tabulated.

The results of the foot examination were documented on a form developed within the CBCHS and used in its diabetic foot clinics. This form was altered by eliminating patient identifiers such as name, village, and phone number. Patients were identified on all forms by an assigned number. Disease-related data included the date of diagnosis and the most recent HbA1c results, if available. For the foot examination, the presence of any deformities was noted, such as ingrown toenails, footdrop, altered gait, Charcot foot, or fixed ankle or great toe joint, as well as whether there was normal range of motion of the foot. Nail bed color and thickness were also noted. Nail hyperkeratosis was noted as “suspicious for onychomycosis.”

The investigators could not do thermal sensation testing, and they did not have access to tuning forks. The skin temperature was recorded as “elevated” or “cool to touch.” It was noted whether pedal pulses were palpable; if they were not palpable, a handheld Doppler device was used to search for a pulse. Ankle-brachial index was assessed on participants whose pulses were not palpable. The presence or absence of foot pain was noted and, if present, whether the pain worsened at night. Participants were asked if they had pain or discomfort that increased with either ambulation or elevation. A monofilament test was done on each patient using a Semmes-Weinstein 5.07 monofilament exerting 10 g of pressure. A 10-point monofilament examination, which is standard in the CBCHS hospital system, was used. The inability to feel 1 of the 10 tested points indicated a failure of the examination.13

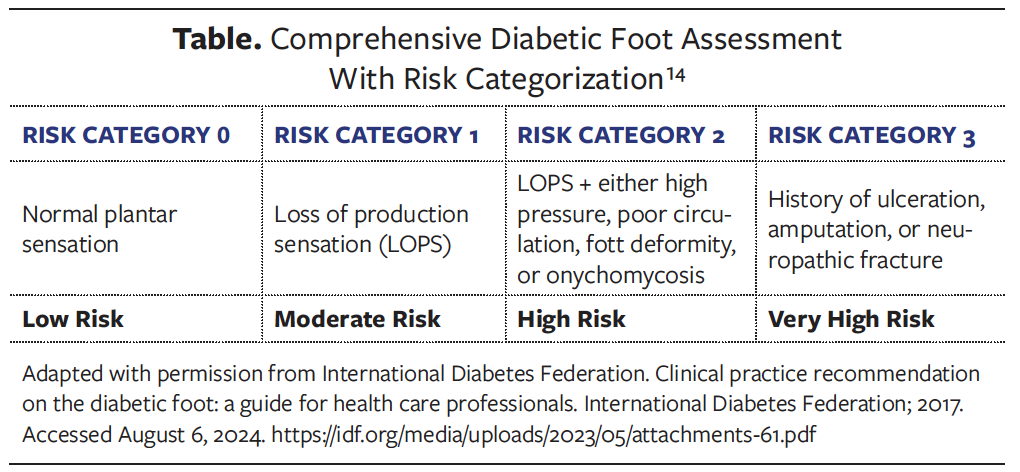

Afterward, using the guidelines in the IDF Clinical Practice Recommendation on the Diabetic Foot–2017, each patient was assigned a risk category based on their history and examination.14 The patient was at low risk (category 0) if they had no evidence of peripheral neuropathy or peripheral vascular disease; at moderate risk (category 1) if there was some loss of protective sensation; at high risk (category 2) if they had some loss of protective sensation plus either an area of high pressure, poor circulation, foot deformity, or onychomycosis; and at very high risk (category 3) if they had a history of ulceration, amputation, or a neuropathic fracture (Table).

Study procedures

The investigators at each hospital were nurses trained in wound care. The onsite wound care supervisor held a training session with the investigators at the onset of the study, reviewing the instructions, the order in which the investigators would present the study parameters, the need for signed consent forms, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The nurse investigators reviewed the knowledge survey and the diabetic foot examination form again with their supervisors at each location before the study commenced. The enrollment and data collection were all done in 1 visit. Inpatients with diabetes who were not in a critical state were invited to participate in the study. Likewise, patients with diabetes seen in the wound care clinic or in a monthly diabetes clinic were invited to participate. Only the nursing investigators could enroll a new patient in the study.

Outcome measures

The patients’ responses to the 5 questions about self-care for their feet were tabulated to identify areas where diabetes education could affect preventative measures to avoid foot wounds and amputations. Using the IDF risk categorization chart, each patient was assigned a risk category based on their history and examination.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corporation). The demographic parameters of all participants were summarized into frequencies and percentages. Bar charts and pie charts were used for nominal variables. Participants who did not answer all questions were treated as “user missing” (dropped) from the particular variables during analysis. The Chi-square test was used to determine the association between variables. Alpha was set at .05 as the level of significance based on a 2-sided test.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 131 respondents were initially enrolled in the study. One enrollee was excluded after it was discovered that she did not have diabetes. The mean (SD) age of the 130 participants was 59.2 (14.4) years (range, 28-101 years). The majority of patients (51.5% [n = 67]) were aged 36 to 40 years. Of the 130 participants, 67 were females (51.5%) and 63 were males (48.5%).

Of the 130 participants, 77.69% (n = 101) indicated that they had never had a foot examination, and 22.31% (n = 29) said they had previously had a foot examination.

Sixty-nine participants (53.10%) either previously or currently had a lower extremity wound. Of these, most (52.2% [n = 36]) consulted more than 2 days after the onset of their wound. Additionally, most consulted at a health facility (76.7% [n = 53]), 3.3% (n = 2) received care from a nurse in the community, 10% (n = 7) went to a traditional healer, and 10% (n = 7) did self-care.

Of the total participants, 15 (11.5%) reported having had an amputation.

Of the 44 participants with a recorded HbA1c value, the mean (SD) HbA1c was 9.8% (3.4%) (range, 4.6%-17.3%). Thirty-six of the 44 patients with a recorded HbA1c value (81.8%) had an abnormal result (>6.5%).

Monofilament test

Monofilament testing revealed abnormal results in 84.6% of patients (n = 110) and normal results in 13.8% (n = 18). One patient did not have a monofilament test due to the location of a large wound, and for another patient the result was not recorded. An equal number of male and female participants had abnormal monofilament tests, while more females had normal results.

Foot care and prevention of complications: participant responses

Patient knowledge about self-care of their feet was determined using a 5-point questionnaire of self-care that is regularly taught when educating patients with diabetes.15 Of the 130 participants in the current study, 39.23% (n = 51) said their feet should be inspected daily; 27.69% (n = 36) said they should seek early treatment for cuts, wounds, or blisters; 11.54% (n = 15) said they should wash their feet well, dry well, and lubricate except between the toes; and 30% (n = 39) said they should always wear well-fitting shoes. This last item was not counted as a positive response if they only mentioned wearing shoes and did not refer to the fit. No participants said that they should avoid extremes of hot and cold, and 40.0% (n = 52) of the participants did not list any of the 5 points (Figure).

IDF risk category distribution

As noted above, based on their history and foot examination, the participants were assigned a risk category per the IDF Clinical Practice Recommendations for the Diabetic Foot.14

The goal of these IDF guidelines is to protect the diabetic foot from skin breakdown and to prevent foot ulceration and lower limb amputations by taking preventative measures early in the disease process. Treatment of the foot in the low risk, moderate risk, and high risk categories (0, 1, and 2, respectively) may prevent advancement to the very high risk category 3.

Results from the 130 patients revealed that 55.38% (n = 72) were at very high risk, 26.15% (n = 34) were at high risk, 5.38% (n = 7) were at moderate risk, and 10.0% (n = 13) were at low risk for foot ulceration and amputation. Four patients (3.08%) could not be categorized due to insufficient data.

An interesting subset of the total 130 patients were the 22 who were diagnosed with diabetes in the previous 3 months. Of those 22 patients, 14 had an active wound and an additional 3 had already had an amputation. Twenty had an abnormal foot examination, including 3 with Charcot foot. Seventeen of the 22 newly diagnosed patients had abnormal results on the monofilament test, indicating that they already had peripheral neuropathy at the time of diagnosis. Overall, 19 of the 22 recently diagnosed patients were in a high risk or very high risk category, indicating that they had advanced foot disease at the time of diagnosis of their diabetes.

Discussion

Using a 5-point knowledge assessment, the investigators of the current study asked patients to list what factors they were aware of for personal foot care and prevention of diabetic foot complications. As noted above, 39.23% of the 130 participants listed awareness of the recommendation for a daily foot examination; 27.69% knew to seek early consultation when symptoms began; and 11.54% said they should wash their feet daily, dry them, and lubricate the skin on their feet. Thirty percent listed the importance of always using protective, well-fitting footwear. No participants listed avoidance of extremes of hot and cold. Forty percent of the patients did not list any of the 5 foot care activities, indicating a lack of knowledge of self-care and measures to prevent foot wounds and amputation. These findings emphasize the need for improved diabetic foot education to equip patients to better care for their feet and thereby avoid foot complications.

Based on the IDF risk categorization for diabetes-related foot complications, 55.38% of the patients were in the very high risk category, and 26.15% were in the high risk category, indicating the extreme vulnerability of this patient population for diabetic foot wounds and amputation.

The study results indicate that most patients with diabetes in the CBCHS clinics and hospitals know little about caring for their feet and how they can prevent complications. Many of the patients enrolled in the current study attended a diabetes clinic at 1 of the 2 hospitals. Although the study investigators did not note whether each participant’s attendance was routine or a 1-time event, those who attended a clinic had at least some access to education on diabetic foot care. These findings also show that 81.52% of patients (n = 106) were in a high risk or very high risk category. This indicates a population with multiple risk factors that are often precursors to diabetic foot infection and eventual amputation, including peripheral neuropathy, a history of previous ulceration, cracks, fissures, and fungal infections.10,15 These results are similar to those from studies done in Tanzania and Nigeria, where similar challenges, such as late arrival, inconsistent care, and a lack of patient education, have been documented.8,16,17

A 2018 study at Mbingo Baptist Hospital found that poorly managed or untreated medical diseases, specifically diabetes and peripheral vascular disease, were the most common reasons for amputations, as opposed to trauma or oncology, further supporting the importance of preemptive patient education to prevent amputations.18

Limitations

One limitation of the current study is the lack of a previously validated standardized form. Additionally, there were no pre- and post-study results to establish a causal relationship between patient education and what participants knew about diabetic foot care. Participants were not thoroughly assessed for peripheral vascular disease in a population at increased risk for this disease. While foot temperature and the presence or absence of pedal pulses were noted, ankle-brachial index screening was not done on each patient. Participants were not questioned about the use of tobacco products. Each person was asked if they had ever had a lower extremity wound, not a foot wound specifically.

Conclusion

Most of the participants in the current study were unable to tell the investigators what they could do to protect their feet and avoid diabetes-related complications. All patients were identified in a hospital or clinic where they were seeking health care. This survey of 130 patients with diabetes indicates that the majority of them (n = 110 [84.6%]) had already lost some protective sensation that puts them at risk for future complications. There is a great need to educate patients in diabetic foot care at the time of diagnosis and at each subsequent visit to a health facility in order to prevent future complications. Medical and nursing staff must also be educated about the principles of diabetic foot care and then incorporate this teaching into every health care encounter with patients with diabetes.

The fact that many patients recently diagnosed with diabetes already had peripheral neuropathy, a wound, or an amputation at the time of diagnosis indicates the need for widespread screening for diabetes in asymptomatic populations. Early diagnosis of diabetes, patient education, and intervention should decrease late complications, including amputation.11

Author & Publication Information

Authors: Carolyn Kohler Brown, BSN, RN, CWCN1; Celestine Kejeh, NA2; Christel Limnyuy, APNA1; Loveline Mboni, SRN, MPH3; Theressia Ngansi, SRN2; Becky Nguesseh, NA1; and Providence Ndim, APNA3

Affiliations: 1Mbingo Baptist Hospital, Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services, Belo subdivision, Cameroon; 2Bafoussam Baptist Hospital, Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services, Bafoussam, Cameroon; 3Nkwen Baptist Hospital, Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services, Bamenda, Cameroon

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board Institutional Review Board (IRB#2021-72) on December 20, 2021.

Correspondence: Carolyn Kohler Brown; Wound Care Educator, Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services, Wound Care, PO Box 1684, Johns Island, SC 29457 USA; ckohlerb@gmail.com

Manuscript Accepted: November 21, 2024

References

1. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1047-1053. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047

2. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 10th ed. Published online 2021. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition

3. International Diabetes Federation. Clinical practice recommendation on the diabetic foot: a guide for health care professionals. International Diabetes Federation; 2017. Accessed August 6, 2024. https://idf.org/media/uploads/2023/05/attachments-61.pdf

4. Boulton AJM, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1719-1724. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67698-2

5. Bakker K, Abbas Z, Pendsey S. Step by step: improving diabetic foot care in the developing world. Pract Diabetes Int. 2006;23(8):365-369. doi:10.1002/pdi.1012

6. Van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J, et al. Definitions and criteria for diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(S1):e3268. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3268

7. Abbas ZG, Lutale J, Archibald LK. Rodent bites on the feet of diabetes patients in Tanzania. Diabet Med. 2005;22(5):631-633. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01488.x

8. Abbas ZG. Managing the diabetic foot in resource-poor settings: challenges and solutions. Chronic Wound Care Manag Res. 2017;4:135-142. doi:10.2147/CWCMR.S98762

9. Abbas ZG, Archibald LK. The diabetic foot in sub-Saharan Africa: a new management paradigm. Diabetic Foot J. 2007;10(3):128-136.

10. Abbas ZG. Diabetic foot – an African perspective. JSM Foot Ankle. 2016;1(1):1005.

11. Lavery LA, La Fontaine J, Kim PJ. Preventing the first or recurrent ulcers. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97(5):807-820. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2013.05.001

12. Abbas ZG, Archibald LK. Challenges for management of the diabetic foot in Africa: doing more with less. Int Wound J. 2007;4(4):305-313. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00376.x

13. Smieja M, Hunt DL, Edelman D, Etchells E, Cornuz J, Simel DL. Clinical examination for the detection of protective sensation in the feet of diabetic patients. International Cooperative Group for Clinical Examination Research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(7):418-424. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.05208.x

14. Adapted with permission from International Diabetes Federation. Clinical practice recommendation on the diabetic foot: a guide for health care professionals. International Diabetes Federation; 2017. Accessed August 6, 2024. https://idf.org/media/uploads/2023/05/attachments-61.pdf

15. Abbas ZG. Preventive foot care and reducing amputation: a step in the right direction for diabetes care. Diabetes Manag. 2013;3(5):427-435. doi:10.2217/DMT.13.32

16. Adigun I, Olarinoye J. Foot complications in people with diabetes: Experience with 105 Nigerian Africans. Diabetic Foot J. 2008;11(1):36-42.

17. Ngim NE, Ndifon WO, Udosen AM, Ikpeme IA, Isiwele E. Lower limb amputation in diabetic foot disease: experience in a tertiary hospital in southern Nigeria. Afr J Diabetes Med. 2012;20(1):13-23.

18. Forrester JD, Teslovich NC, Nigo L, Brown JA, Wren SM. Undertreated medical conditions vs trauma as primary indications for amputation at a referral hospital in Cameroon. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(9):858-860. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1059