Diagnosing Pressure Injuries—Why History, Context, and Caution Still Matter

A SAWC Fall session on pressure injuries urged clinicians to slow down, broaden the diagnostic lens, and avoid shortcuts derived from electronic health records, photographs, or emerging artificial intelligence (AI) tools. The session was framed around a simple but often overlooked imperative: “Look at the whole patient.” That theme anchored case vignettes and practical reminders about how misclassification occurs and how to prevent it.

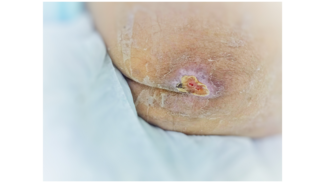

The presentation opened by distinguishing true pressure injuries from look-alike lesions that share surface features but differ in cause, risk, and management. The speaker, Samuel Nwafor MD, FACP, FAPWCA, emphasized that busy inpatient workflows, cross-coverage, and variable training can promote pattern recognition at the expense of a deliberate differential diagnosis. During admissions and handoffs, essential elements of the history are frequently lost; however, a careful history remains the diagnostic anchor. “There are so many things that look like pressure,” Nwafor noted, underscoring how trauma, device-related injury, moisture-associated skin damage, ischemia, and dermatologic conditions can mimic pressure patterns.

Several cases illustrated how anchoring on a label—especially one inherited from another setting—can obscure the true etiology. Documentation inertia was a recurring contributor: a term carried forward in notes or a templated description that hardened into a diagnosis without bedside re-examination. Nwafor encouraged clinicians to spend “a few precious minutes before you walk into the room” reviewing the clinical course and then verifying it against the patient’s current physiology, mobility, devices, and microenvironment (bed, chair, splints, lines).

Training variability emerged as a modifiable risk. New staff, float teams, and cross-disciplinary coverage benefit from concise, scenario-based refreshers that contrast pressure injury morphology with common mimics. The session also highlighted the operational pressures that favor rapid clicks over nuanced description, a dynamic that increases downstream utilization—consultations, testing, and treatments—when the initial label is incorrect.

Technology received both praise and caution. Bedside photography can aid serial assessment and communication, but images decontextualize the patient and flatten nuance. Nwafor also warned against uncritical reliance on algorithms trained on narrow datasets: “We have to be very careful as to how we form this future and what type of algorithms are being used to train the artificial intelligence software.” If datasets underrepresent diverse skin tones, body habitus, or care environments, tools may propagate bias—misclassifying lesions or missing early changes in populations for whom accuracy is most critical.

Ultimately, the session advocated disciplined clinical reasoning over reflex. Clinicians should revisit the differential at each transition, interrogate discordant details, and avoid carrying forward a diagnosis that no longer fits. Photographs and decision aids should support—not replace—hands-on examination and patient-specific context.

Key Takeaways for Practice

• Recenter the bedside examination. Begin with the history and a full-skin, device-aware assessment before accepting a prior label. When uncertain, describe findings in plain terms and rebuild the differential.

• Audit care transitions. At admission, transfer, and discharge, verify that the wound etiology aligns with the evolving clinical picture. Do not allow templated language or inherited documentation to substitute for an independent assessment.

• Train for look-alikes. Provide brief, recurring education that contrasts pressure injuries with device-related trauma, moisture/irritant damage, ischemic lesions, and dermatologic mimics to reduce misclassification.

• Use images judiciously. Bedside and telehealth photographs are helpful for trend tracking, but they cannot convey pressure, perfusion, pain, or device forces. Pair images with in-person findings.

• Scrutinize AI outputs. Treat algorithmic suggestions as prompts rather than verdicts—particularly in diverse patient populations and across skin tones. Demand diverse training data and transparency.

The session concluded where it began: with clinical curiosity. Each wound is an opportunity to test assumptions, align diagnosis with mechanism, and tailor treatment to the person, not merely to the picture.