The Use of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in Assessment of Viability and Monitoring of Healthy Trajectories in Skin Tears

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Reliable methods of assessing skin tear flap viability beyond visual inspection would conserve flap tissue and improve outcomes. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is a noninvasive, noncontact means of assessing the oxygenation and perfusion status of superficial tissue. Objective. To determine the viable cross-sectional skin flap area in jeopardized skin flaps using NIRS and to determine the average time to heal of conserved skin flaps compared with historical data. Methods. A single-center prospective cohort study was performed at Madigan Army Medical Center between June 2023 and July 2024. Skin flaps were assessed for viability using NIRS. Conservation of skin flaps instead of flap resection leads to a reduction in wound size. Time to heal of the preserved skin flaps was recorded. Results. The median wound cross-sectional area without the preserved skin flap (9.1 cm2 [IQR, 4.2 cm2-11.7 cm2]) was significantly larger than with the preserved skin flap (1.6 cm2 [IQR, 0.9 cm2-2.9 cm2]; P = .0001). The median time to heal with preserved skin flaps was 22 days (IQR, 21 days-41 days) in the present study, compared with 28 days to 42 days in the literature (P = .82). Conclusion. Although this study was underpowered, wound healing times were shorter than historical averages, suggesting that NIRS is a useful tool for assessing tissue viability and conserving skin flaps that have adequate oxygenation.

Skin flaps are common, and the clinical question is whether to excise or preserve the skin flap. Historically, if skin flaps appeared dusky or started to fail, typically the whole skin flap was removed, creating a larger wound and a delay in healing. However, with removal of the anatomically displaced tissue created by a skin flap, the skin flap cannot act as a skin graft for the areas of tissue that are still viable. Such removal is largely due to imprecision or inability to determine skin flap viability, which has historically been tied to physician gestalt and visual inspection.

Skin tears can be staged following the International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP) Classification System.1 A type 1 skin tear is a linear or flap tear that can be reapproximated to cover the wound bed. A type 2 skin tear involves partial flap loss that cannot be fully reapproximated to cover the wound bed. Type 3 skin tears involve total flap loss, leaving no tissue to cover the wound bed.1 Whenever possible, it is desirable to preserve viable skin flap tissue and prevent the creation of type 2 or type 3 tears with unnecessary debridement. A reliable method of assessing skin flap viability beyond visual inspection would be of immense benefit and likely would result in preservation of more skin flaps and improved outcomes.

One possible method of assessing skin flaps is noncontact near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), which has been used extensively in wound care,2,3 surgical applications,4 and determination of skin flap viability.5-7 As stated by the manufacturer, NIRS uses emitted and reflected wavelengths of near-infrared light (500 nm-900 nm) to determine relative amounts of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin within superficial tissue (SnapshotNIR, Kent Imaging Inc). The relative amounts of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin together can be used as a marker of tissue oxygen saturation (StO2). Assuming that tissue is metabolically active, the level of StO2 can be informative of whether the tissue is perfused. As perfusion is reduced, tissue oxygen extraction increases, causing StO2 to drop to match the metabolic demand.8 As a result, NIRS can be used to noninvasively determine a relative level of perfusion that can provide information on which areas of a skin flap are viable. Additionally, because ischemia is an independent risk factor for skin flap viability,9 assessment of ischemia at the point of care may provide a better understanding of whether a skin flap will fail.

A single-center prospective cohort study was conducted to determine whether using NIRS to assess skin flap viability would lead to flap preservation and shorter times to heal. The aims of this study were to (1) determine the cross-sectional skin flap area that can be preserved when using NIRS to determine skin flap viability and (2) assess the average time to closure using preserved skin flaps to observe if this approach provides benefit compared with historical closure times. The authors of the current study hypothesized that NIRS would be a useful determinant of skin flap viability, resulting in less skin flap excision and reduced healing times compared with the standard 4- to 6-week healing times seen in the literature.10,1

Methods

Study design

This was a single-center prospective cohort study performed at Madigan Army Medical Center in Fort Lewis, WA, between June 2023 and July 2024.

Patients who presented with a skin flap were clinically assessed for viability of tissue. After clinical assessment, patients underwent NIRS to determine the viability of tissue. Tissue exhibiting deoxyhemoglobin values greater than or equal to 0.5 was deemed nonviable and was sharply debrided to prevent infection risk. Any tissue exhibiting StO2 values greater than or equal to 50% was deemed viable and was approximated to normal anatomical position to continue monitoring at subsequent visits. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. This study was deemed exempt from IRB approval given that there were no changes in the standard of patient care.

To determine viability of skin flaps, tissue with a deoxyhemoglobin value greater than 0.5 or an StO₂ value less than 50% was classified as nonviable. Nonviable areas of tissues were excised.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R Software (version 4.3.1; The R Project for Statistical Computing). Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Data are presented as median (IQR). Cross-

sectional wound areas with and without preserved skin flaps were compared using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. The median time to heal was compared with the lower end of wound healing times in the literature (ie, 28 days) using a 1-sample Wilcoxon test.10,11

Results

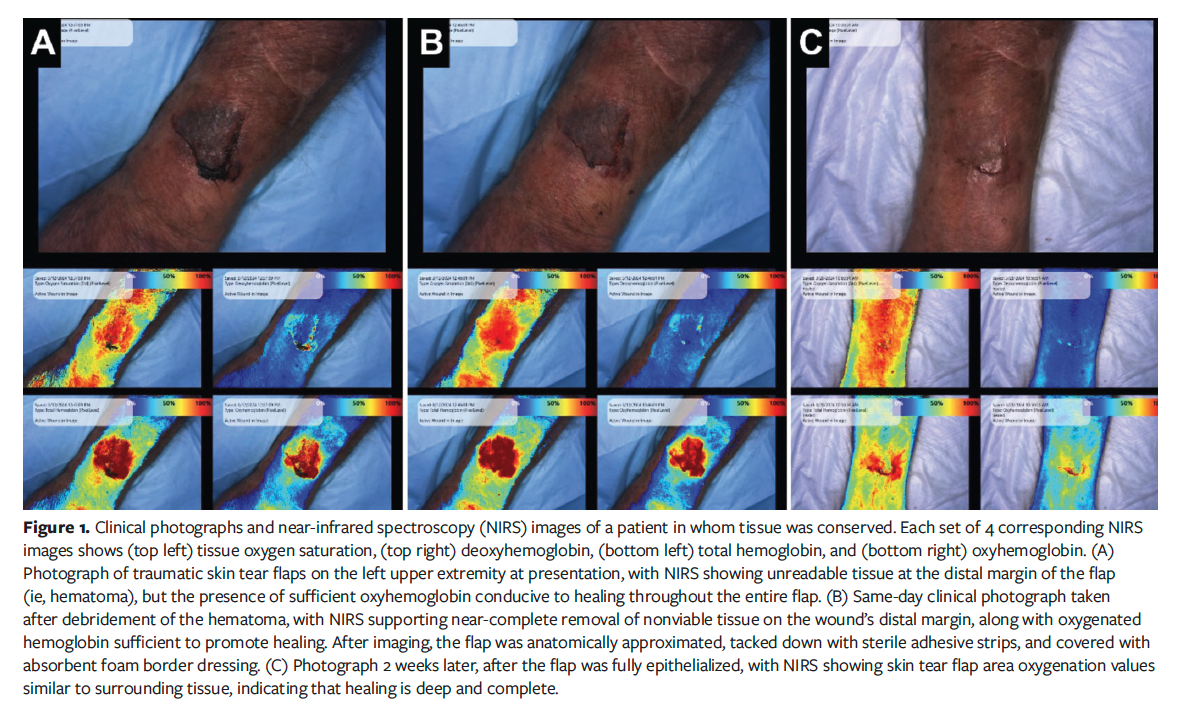

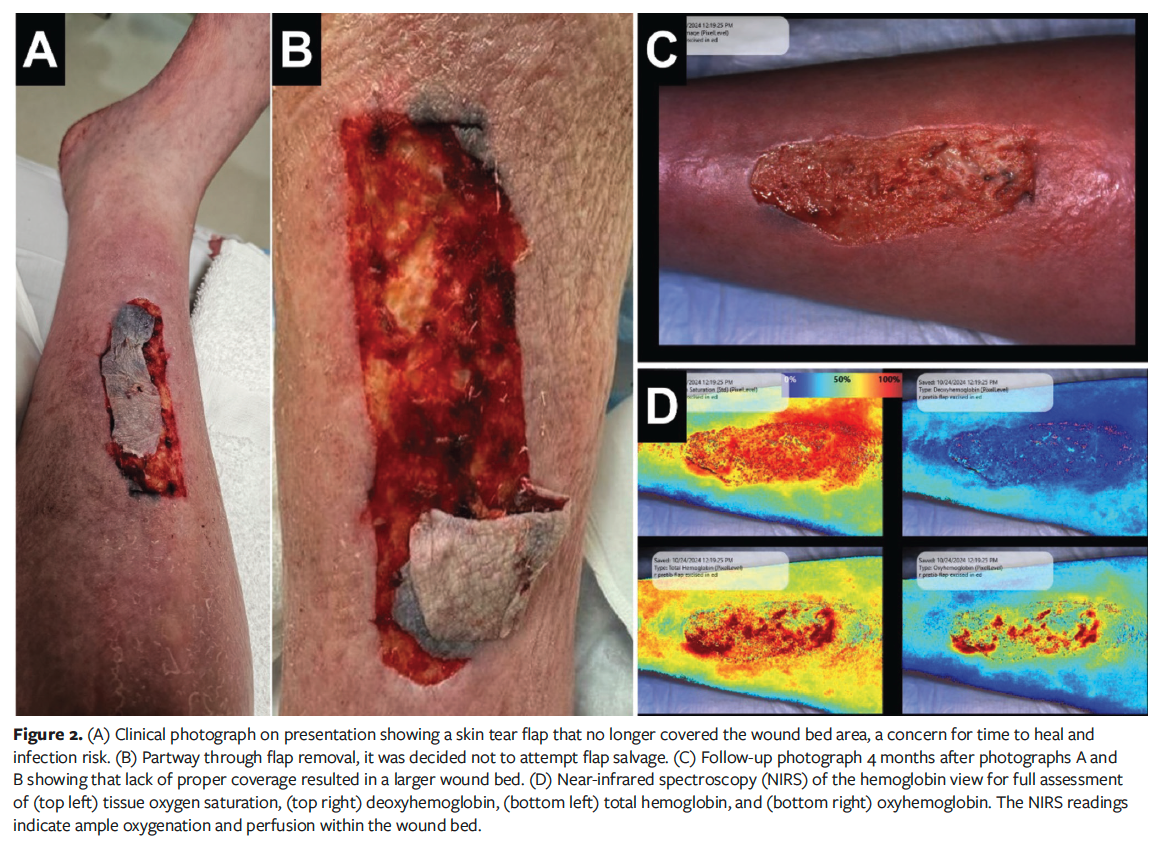

Fourteen skin flaps in 11 patients were studied. The mean patient age was 71 years (range, 26 years-94 years). Eight of the 11 patients had comorbidities, including a history of cancer, congestive heart failure, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Figure 1 demonstrates a case of a successful skin flap conservation and healing process. Skin flaps that did not heal either had contamination prior to initial presentation or occurred in patients with venous disease, which led to excess tension and maceration of skin flap tissue. Figure 2 is an example of deciding not to attempt to salvage a skin flap, resulting in a larger wound.

History of disease did not seem to correlate strongly with the outcome of skin flap healing, however. The oldest patient studied was a 94-year-old male with a history of abdominal aortic aneurysm, anemia, coronary artery disease, stage 3 chronic kidney disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. He presented with a traumatic skin flap to the left radius. NIRS demonstrated values consistent with eschar and nonviable tissue along the distal margin of the skin flap. This was debrided, and the remaining viable skin flap was approximated to normal anatomical position and affixed with sterile adhesive strips. On the next visit, 6 days after initial presentation, the skin flap had begun reepithelialization to reattach to the surrounding skin. The wound was reassessed, and no nonviable tissue was detected. Sixteen days after initial presentation, deep wound healing was noted with 100% coverage and minimal residual inflammation detected by NIRS.

The median wound cross-sectional area without the preserved skin flap (9.1 cm2 [IQR, 4.2 cm2-11.7 cm2) was larger than with the preserved skin flap (1.6 cm2 [IQR, 0.9 cm2-2.9 cm2]; P = .0001). The median relative reduction in wound size with preserved skin flaps was 78% (IQR, 63%-84%), and the median absolute reduction in wound size with preserved skin flaps was 6.2 cm2 (IQR, 2.4 cm2-10.1 cm2).

The median time to heal with preserved skin flaps was 22 days (IQR, 21 days-41 days) in the present study, compared with 28 days to 42 days in the literature (P = .82).10,11

Discussion

The present study has several important findings: preserved skin flaps reduced the cross-sectional area of wounds, and, although underpowered and not statistically significant, there was a reduction in healing times with preserved skin flaps compared with the majority of reported healing times in the literature (ie, within 4.3 weeks).10 The findings in the present study have immediate implications for implementing objective measures of tissue viability that can preserve skin flap tissue and reduce wound sizes and healing times. These benefits would be best realized if NIRS were used in the emergency room.

Patients often present to the emergency room with traumatic skin flaps, which are promptly removed. This immediate removal of skin flaps is highly detrimental because any epidermal coverage is stripped away, thus creating a larger wound and increasing the healing time, resulting in a setback in the healing process. Such removal of any healthy tissue is a net loss, because healthy tissue provides a growth matrix for new tissue growth while also providing innate immune protection from infection by covering the wound. As such, preservation of skin flaps offers patients benefits beyond healing times. While the authors of the current study recognize that common practices and standards support the complete removal of traumatic skin flaps at presentation, the authors contest that practice standards need to be updated to prevent unnecessary re-epithelial formation that could be achieved with preservation of existing skin flaps. Although the best way to determine tissue viability is yet to be determined, monitoring skin flaps with NIRS for assessment of oxygenation and metabolic activity is a logical step forward in physiologic assessment of tissue.

Based on publicly reported wound healing rates, the time to heal for 30 clinics varied from 2.7 weeks to 16 weeks, with the majority of clinics reporting healing within 4.3 weeks.10 At the low end, wound time to healing of approximately 19 days (2.7 weeks) is the best time reported in the literature and is the closest to the median time to heal of 22 days in the current study. While it is hard to draw conclusions concerning why times to heal were similar or different without comparing patient demographics, wound etiologies, comorbidities, and treatment processes, this initial report of approximately 3.1 weeks (22 days) to heal found in the current study is the second-fastest healing time out of 31 centers (compared with the 30 clinics reported by Fife et al10). Thus, while the current study is statistically underpowered to definitively say that the wound healing times found are better than average, anecdotally it seems that preserving skin flaps leads to smaller wounds and to an appreciable reduction in wound healing times.

To determine when a skin flap should be preserved, an objective measure of tissue viability is imperative. While different modalities exist to determine tissue oxygenation and perfusion (eg, transcutaneous oxygen measurement, skin perfusion pressure), they often take considerable time to use or have costs associated with their use. NIRS was used in the present study because it is noncontact, noninvasive, and provides assessment results in less than a minute, allowing it to be readily incorporated into the clinical workflow. While NIRS has proven effective in determining when skin flaps are going to fail,5,6 the precise characteristics that indicate the timing of such failure still need to be determined. The present study used 50% StO₂ based on the study authors’ experience using the NIRS device, but a more conservative approach (eg, 60% StO2) may be more representative of tissue viability in a larger cohort. As assessment modalities are tried and calibrated for tissue viability, the next step would be to arrive at some clinical agreement on which modalities best assess tissue viability and what thresholds should be used. Based on the present investigation, NIRS is a strong contender for being the modality of choice for clinicians to assess skin flap preservation.

Previous work has demonstrated that 3 months after injury, the tensile strength of wounds peaks at 80% of uninjured skin and does not return to 100%.11 Such a reduction in durability likely leads to an increased chance of reinjury and longer healing time.11 With skin flap preservation, however, tensile strength is likely preserved because the tissue originates from an uninjured location. As such, preservation of skin flaps is likely superior to the traditional approach of allowing full reepithelialization as tissue integrity is augmented. Future work comparing tensile strength and occurrence of reinjury in wounds healed by preserved skin flaps vs reepithelialization alone would provide immense benefit because skin flaps likely have additional benefits beyond shorter healing times.

There are also major economic implications of reducing time to heal.12 Billing records show that as of June 2024, a single visit to the Wound Care Clinic at Madigan Army Medical Center costs approximately $200 to either the patient or the insurer. Reducing patient follow-up by 1 week to 2 weeks could save $200 to $400 per patient. Using the number of patients in this study (n = 11), the approximately 2200 specialty wound care clinics in the United States, and the savings of a single visit ($200), this would amount to an annual national savings of $5 million at the absolute lowest end of economic benefit. It is also worth noting that a 5-year retrospective analysis of the US Wound Registry found that jeopardized skin flaps and grafts cost $9358 on average to heal.13,14 While a NIRS device carries an initial upfront capital expenditure, the device will last years, and the burden of cost can be spread between patients and insurance, similar to other advanced vascular testing equipment. In addition to the cost of a NIRS device, wound care facilities would need to train staff (eg, vascular technician, nurse, physician) on the correct use of the device.

Limitations

The current study has multiple limitations worth considering. First, skin flap viability was assessed based on StO2 above 50%. Because skin pigmentation is known to affect StO₂ values,15,16 this arbitrary threshold may cause darker pigmented skin flaps to appear less viable compared with lighter pigmented skin flaps. This, however, is likely not an issue in the current study because any preservation of skin flap would still be better than nothing. Future work should aim to determine the optimal skin flap viability threshold value based on skin flap pigmentation. Second, this study was underpowered, with 14 skin flaps. Because wound healing times are highly variable, a greater number of skin flap cases would provide a better comparison with the existing literature on whether wound closure times are different with preserved skin flaps. Third, this study did not include historical controls without NIRS assessment, and cases were not randomized to control vs preserved skin flap study arms. The authors of the present study have had the best closure success with NIRS assessment of skin flap viability, and it is part of the standard of care at the aforementioned wound healing center; thus, wound closure times were compared against the literature. As such, comparisons to population data are possible; however, there likely are differences in wound and patient treatments that obfuscate the utility of NIRS when compared within the authors’ own practice. Future work should involve NIRS assessment of skin flap viability vs within-center controls and include a multicenter approach to increase generalizability.

Conclusion

Preservation of traumatic skin flaps reduced cross-sectional wound areas while protecting against infection, providing tensile strength, and reducing the amount of reepithelialization required for wound closure. Times to heal were reduced by approximately 1 week when preserved skin flaps were used compared with average time to heal within the literature. NIRS aided in determining the viability of skin flap tissue, which allowed the preservation of tissue and reduced healing times. Clinical standards should be updated to utilize NIRS or other modalities to assess tissue viability and thereby preserve tissue and reduce times to heal in patients with wounds.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Homer-Christian J. Reiter, MS, BSc1,2,3; and Charles Andersen, MD, MAPWCA2,3,4

Affiliations: 1Pacific Northwest University of Health Sciences College of Osteopathic Medicine, Yakima, WA, USA; 2Madigan Army Medical Center, Joint Base Lewis-McChord, WA, USA; 3University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; 4Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, USA

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: Informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study.

Correspondence: Charles Andersen, MD, 9040 Jackson Ave, Tacoma, WA, 98431; cande98752@aol.com

Manuscript Accepted: August 11, 2025

References

1. Van Tiggelen H, LeBlanc K, Campbell K, et al. Standardizing the classification of skin tears: validity and reliability testing of the International Skin Tear Advisory Panel Classification System in 44 countries. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(1):146-154. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18604

2. Reiter HCJ, Andersen CA. Near-infrared spectroscopy with a provocative maneuver to detect the presence of severe peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2023;10(6):101379. doi:10.1016/j.jvscit.2023.101379

3. Landsman A. Visualization of wound healing progression with near infrared spectroscopy: a retrospective study. Wounds. 2020;32(10):265-271.

4. Geskin G, Mulock MD, Tomko NL, Dasta A, Gopalakrishnan S. Effects of lower limb revascularization on the microcirculation of the foot: a retrospective cohort study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(6):1320. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12061320

5. Hill WF, Webb C, Monument M, McKinnon G, Hayward V, Temple-Oberle C. Intraoperative near-infrared spectroscopy correlates with skin flap necrosis: a prospective cohort study. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(4):e2742. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002742

6. Jones GE, Yoo A, King VA, Sowa M, Pinson DM. Snapshot multispectral imaging is not inferior to SPY laser fluorescence imaging when predicting murine flap necrosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(1):85e-93e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006405

7. Rammos CK, Jones GE, Taege SM, Lemaster CM. The use of multispectral imaging in DIEP free flap perforator selection: a case study. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(11):e3245. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000003245

8. Bird JD, MacLeod DB, Griesdale DE, Sekhon MS, Hoiland RL. Shining a light on cerebral autoregulation: are we anywhere near the truth? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2024;44(6):1057-1060. doi:10.1177/0271678X241245488

9. Iamaguchi RB, Takemura RL, Silva GB, et al. Peri-operative risk factors for complications of free flaps in traumatic wounds - a cross-sectional study. Int Orthop. 2018;42(5):1149-1156. doi:10.1007/s00264-018-3854-6

10. Fife CE, Eckert KA, Carter MJ. Publicly reported wound healing rates: the fantasy and the reality. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2018;7(3):77-94. doi:10.1089/wound.2017.0743

11. Almadani YH, Vorstenbosch J, Davison PG, Murphy AM. Wound healing: a comprehensive review. Semin Plast Surg. 2021;35(3):141-144. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1731791

12. Olsson M, Järbrink K, Divakar U, et al. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: a systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27(1):114-125. doi:10.1111/wrr.12683

13. Nussbaum SR, Carter MJ, Fife CE, et al. An economic evaluation of the impact, cost, and Medicare policy implications of chronic nonhealing wounds. Value Health. 2018;21(1):27-32. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2017.07.007

14. Fife CE, Carter MJ. Wound care outcomes and associated cost among patients treated in US outpatient wound centers: data from the US Wound Registry. Wounds. 2012;24(1):10-17.

15. Patel NA, Bhattal HS, Griesdale DE, Hoiland RL, Sekhon MS. Impact of skin pigmentation on cerebral regional saturation of oxygen using near-infrared spectroscopy: a systematic review. Crit Care Explor. 2024;6(2):e1049. doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000001049

16. Suludere MA, Tarricone A, Najafi B, et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy data for foot skin oxygen saturation in healthy subjects. Int Wound J. 2024;21(3):e14814. doi:10.1111/iwj.14814