Successful Treatment of a Scalp Arteriovenous Malformation With Ulcerative Hemorrhage and Localized Alopecia

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Scalp arteriovenous malformation (AVM) and its clinical course associated with ulcerative hemorrhage and local alopecia are rarely reported. Case Report. An 18-year-old male presented to a vascular anomalies center with scalp AVM and ulcerative hemorrhages over a 6-month period due to post-excision recurrence, initially associated with thinning hair and scalp erythema around the AVM lesion. After meticulous debridement, the patient was immediately given an ethanol embolization. He was advised against home wound care to prevent possible hemorrhage. After several effective interventional sessions over an 18-month period, not only was the AVM lesion extensively eliminated, but restoration of hair growth around the lesion was observed. This phenomenon may be attributed to the alleviation of deep, high-flow AVM steal phenomenon, which in turn restored normal blood supply to superficial layers, promoting ulcer healing and hair regrowth. Conclusion. This report suggests that scalp AVMs can be accompanied by AVM-related alopecia, which may recover after ethanol embolization. This report also suggests that restrictive debridement during multiple intervention sessions can be feasible in ulcerated AVMs with a high risk of hemorrhage.

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are high-flow vascular malformations that can arise from genetic mutations or trauma.1,2 Cutaneous and soft tissue AVMs present clinically as pulsatile swellings with skin erythema and elevated skin temperature. Pathologically, AVMs are characterized by the absence of normal capillary beds, resulting in microfistulae, dilated and tortuous vessels forming a tangled vascular mass, and pathological venous hypertension.3 Notably, scalp AVMs may be associated with localized alopecia at the affected site, although this association is rarely reported. Surgical resection may lead to recurrence due to unavoidable residual abnormal lesions; interventional embolization may be a more effective treatment option instead.1,4

This report presents a case of a patient with postoperative recurrent scalp AVM, presenting with massive hemorrhage and alopecia. The AVM symptoms and localized alopecia improved following interventional embolization with limited debridement. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient, permitting the publication of the case details and images.

Case Report

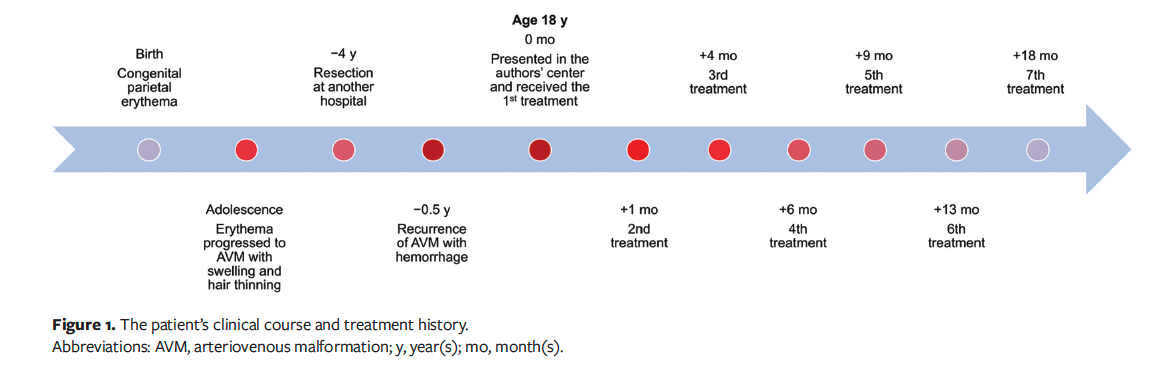

An 18-year-old Han Chinese male presented to the Vascular Anomalies Center of the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital, with a severely crusted and bandaged scalp wound on the parietal region. He reported a history of a simple erythema without soft tissue swelling on the parietal region since birth, which gradually developed into a pulsatile and warm swelling during adolescence, accompanied by hair loss and thinning in the affected area. Following surgical resection of the scalp AVM at another hospital, the lesion rapidly enlarged and ulcered, with recurrent hemorrhage (Figure 1). The patient had been applying a dressing to control the bleeding at the time he presented to the authors’ center. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) heart function classification and echocardiography ruled out AVM-related heart failure, and the AVM was classified as Schobinger stage III.5 The patient also reported persistent low-grade fever and anemia since the ulceration. There was no family history of AVMs or cutaneous erythema.

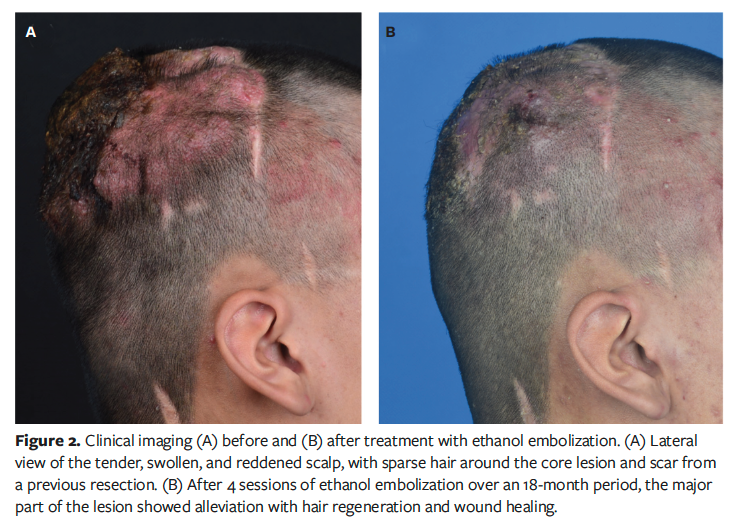

The dressing was removed gently with saline, revealing an erythematous, raised, and tender scalp with a previous coronal scar. Sparse hair and palpable pulsatile masses were evident around the central affected area (Figure 2A). The wound was purulent and malodorous, with maggots, consistent with a chronic infected state.

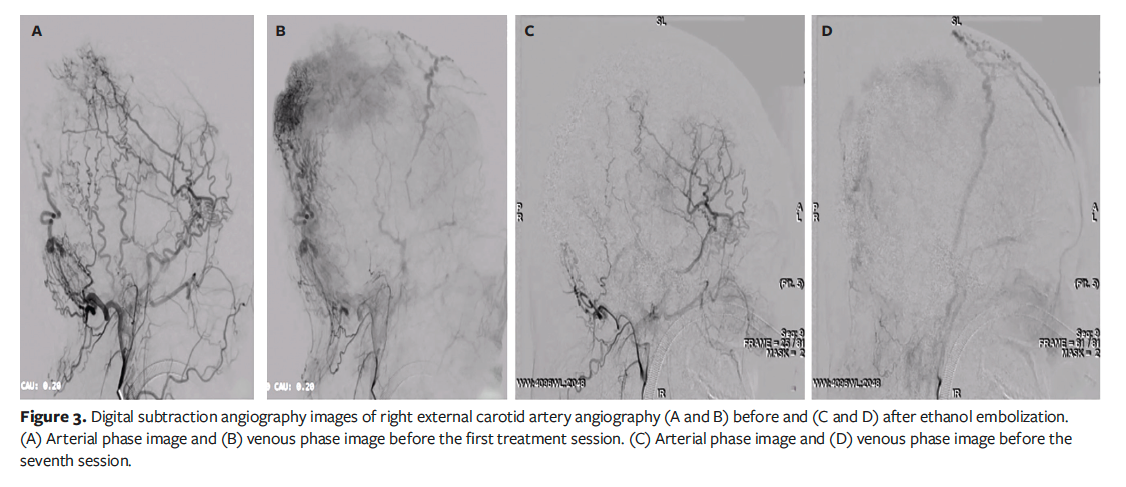

Given the high risk of hemorrhage due to the high intravascular pressure within the lesion, ethanol embolization was performed under digital subtraction angiography (DSA) guidance and general anesthesia.6 A percutaneous femoral arterial sheath was placed using the Seldinger technique. Bilateral internal carotid angiography and vertebral angiography ruled out intracranial AVM. Subsequent bilateral external carotid angiography via a vertebral catheter delineated lesion vascularization deriving from bilateral occipital and superficial temporal arteries with right-sided dominance. Then, meticulous debridement of the wound was performed. Puncturing access to hemorrhagic foci was achieved under DSA guidance using 22-gauge needles. Focal fistulae were verified through local contrast injection prior to injecting absolute ethanol in 2-mL aliquots via the needle. An iterative sequence of manual contrast injection followed by ethanol embolization was performed at multiple puncturing sites. The first treatment was terminated upon achieving a cumulative ethanol dose of 0.5 mL/kg, followed by meticulous layered wound dressing using sequential absorbable hemostatic cellulose fabric and gelatin sponge, petrolatum gauze, cotton gauze, and cotton bandage, all wrapped with a tubular elastic net head bandage. After the first treatment, the hemorrhage was controlled, but the main body of the AVM persisted. To minimize the risk of accidental hemorrhage, the patient was advised against any kind of home wound care, such as self-debridement, and was urged to undergo debridement during subsequent treatments at the authors’ center. This advice was given after a thorough discussion with the patient. He agreed, and hemorrhage was not encountered during this period.

The patient underwent 6 further embolization sessions over the following 18 months, each accompanied by thorough debridement (Figure 1). No antibiotics were administered throughout the treatment course. After a total of 4 ethanol treatments, follow-up DSA revealed a significant reduction in the abnormal vascular network (Figure 3). Clinically, the patient’s wound healed, the pulsatile mass disappeared, and the scalp flattened significantly (Figure 2B). Unexpectedly, hair regrowth was observed in the previously alopecic areas of the patient’s scalp. The affected areas, characterized by sparse hair and erythema, showed a significant increase in hair density and thickness following ethanol embolization. However, the original coronal surgical scar and some small scars at the treatment site remained.

Discussion

with AVM with ulceration and massive hemorrhage should be extremely cautious. Any temptation to debride should be avoided, despite the presence of purulent exudate in the ulcerated wound. Any debridement involving removal of dressings and fluid lavage is risky, because the wound is friable and highly susceptible to rupture and massive hemorrhage, leading to fatal hypovolemic shock.

In the present case, except for the first procedure, all debridements were performed in the angiography suite. The patient was advised to avoid any debridement at home or in primary care centers between treatments, because patients and primary care practitioners may have insufficient understanding of the risks associated with AVMs. Usually, patients with AVM are concerned about the infection status of the wound, so these medical recommendations require thorough communication and risk disclosure between the doctor, patient, and family.

Debridement of ulcerated AVMs requires methodical precision. Existing dressings should be removed layer by layer with adequate saline wetting. Dressings that are dry with the tissue should be gently separated. After complete separation, the wound should be rinsed with alternating saline and 0.05% povidone-

iodine solutions. Notably, to avoid compromising healing, the authors of the present report did not use hydrogen peroxide in all debridements in this case. Granulation oozing and minor bleeding is acceptable and patients can be allowed to continue debridement, whereas inadvertent lesion rupture accompanied by arterial pulsatile hemorrhage, as occasionally occurred in the present case, necessitates immediate ethanol treatment targeting the hemorrhagic site.

The dressing used after each treatment was selected primarily based on the risk of hemorrhage. For lesions with a high risk of bleeding, absorbable hemostatic materials were used, such as cellulose fabrics and gelatin sponges in the innermost layer, followed by petroleum gauze to lubricate and reduce local adhesions, and finally covered with cotton gauze and wrapping bandage. Through successive ethanol treatment sessions achieving therapeutic cumulative dosimetry, the risk of hemorrhage decreased, and the hemostatic materials were gradually discontinued. Additionally, as the tissue grew and the granulation of the wound completed epithelialization, the discontinuation of any dressings or coverings could also be considered.

Throughout the treatment period, the improvement of the scalp ulcer and infection was gradual and synchronous, although the temporal relationship between the restoration of the skin barrier and the improvement of infection in the disease course remains unclear. However, it is clear that the improvement of infection in this case was not delayed due to limited debridement.

To the knowledge of the authors of the present report, there have been no reports of regional alopecia associated with scalp AVMs. However, this phenomenon appears to be explainable by pathophysiological theory.

From a pathophysiological and hemodynamic perspective, AVMs introduce a low-resistance pathway into the local circulation, diverting blood flow away from the high-resistance cutaneous capillary bed, leading to ischemic changes known as the “steal phenomenon.”7 Previous studies have suggested that this phenomenon is the mechanism underlying ulceration in AVM lesions. The authors of the present report hypothesize that this mechanism may also contribute to hair loss in patients with scalp AVMs—the diverted blood flow reduces the adequate nutrient supply to hair follicles, disrupting the local microenvironment and promoting hair loss. By interventional embolization, ethanol destroys endothelial cells in abnormal vessels, forming microthrombi.8 Following treatment, the low-resistance AVM pathway is disrupted and occluded, reversing the steal phenomenon and restoring normal blood flow to the capillary bed supplying hair follicles. Therefore, reperfusion of capillaries in the follicular layer may be crucial for hair regeneration.9

Although these speculations are not supported by skin biopsy (considering the risk of bleeding and difficulty in hemostasis), they are corroborated by similar findings reported by Ünlü and de Vries.10 Those authors described a patient with severe occlusion of the branches of the aortic arch who experienced complete recovery of alopecia and scalp ulceration after vertebral artery stent placement. In ischemic alopecia and ulceration due to insufficient blood supply, the primary aim of treatment is to correct the reduced blood flow in the superficial skin caused by the lesion. In AVMs, this is achieved by occluding the high flow of the fistula using embolic agents or embolic materials.

In peripheral AVMs, absolute ethanol embolic agents are more commonly used due to their non-retention, biodegradability, and unique chemical cytotoxic effect on endothelial cells. Other liquid embolic agents, such as glue and Onyx (Medtronic), act in a different mechanism. They are injected in liquid but solidify and form casts within the vessel and are much less effective than ethanol in killing endothelial cells.11 The use of the aforementioned liquid embolic agents may cause cosmetic changes, and there are reports of some long-term recanalization.12,13 Ethanol embolization may need to be performed under general anesthesia by an experienced surgeon or interventional radiologist. The dose of ethanol is limited by body weight, and in the clinical practice of the authors of the present report, the dosage per treatment generally does not exceed 0.5 mL/kg. There have also been reports of dosage up to 1 mL/kg, but this is associated with a high risk of fatal cardiovascular events.14 For stable patients with AVM, there should be at least a 2-month interval between treatments.

Although the scalp of the patient in the present report was exposed to angiography-

related X-rays during multiple treatments, there was no radiation-induced hair loss as previously reported.15

Limitations

Although this case report discusses effective protocols for the treatment and management of scalp AVMs at risk for bleeding and baldness, it has limitations. The most important limitation is the lack of pathologic evaluation of the ulcerated granulation tissue and areas of alopecia to clarify the patterns of wound recovery and hair growth.

Conclusion

The authors of the present report successfully treated a case of scalp AVM with ulceration, hemorrhage, and localized alopecia using ethanol embolization. Appropriate interventional embolization is crucial for wound healing and hair regrowth of scalp AVMs. For safety reasons, clinicians may consider limiting debridement in patients with AVMs accompanied by massive hemorrhage. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying localized alopecia caused by scalp AVMs.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Yuxi Chen, MD; Bin Sun, MD, PhD; Xi Yang, MD, PhD; Chen Hua, MD, PhD; and Xiaoxi Lin, MD, PhD

Affiliations: Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Acknowledgments: Drs Chen and Sun contributed equally to this manuscript.

Disclosure: This report is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (YG2023ZD13), the Top Priority Research Center of Shanghai–Plastic Surgery Research Center, Shanghai (2023ZZ02023), and the Fundamental Research Program Funding of Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (JYZZ241). The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this report.

Ethical Statement: The report has been waived from ethical review by the institutional review board of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital. Written patient consent was obtained for the publication of recognizable patient photographs or other identifiable material, with the understanding that this information may be publicly available.

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this report are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Correspondence: Chen Hua, MD, PhD; Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, No. 639 Zhizaoju Road, Shanghai 200011, China; E-mail: worson78@163.com

References

1 Liu AS, Mulliken JB, Zurakowski D, Fishman SJ, Greene AK. Extracranial arteriovenous malformations: natural progression and recurrence after treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(4):1185-1194. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d18070

2 Couto JA, Huang AY, Konczyk DJ, et al. Somatic MAP2K1 mutations are associated with extracranial arteriovenous malformation. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(3):546-554. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.018

3 Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(3):412-422. doi:10.1097/00006534-198203000-00002

4 Hua C, Jin Y, Yang X, et al. Midterm and long-term results of ethanol embolization of auricular arteriovenous malformations as first-line therapy. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(5):626-635. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2018.01.017

5 Kohout MP, Hansen M, Pribaz JJ, Mulliken JB. Arteriovenous malformations of the head and neck: natural history and management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(3):643-654. doi:10.1097/00006534-199809010-00006

6 Jin Y, Yang X, Hua C, et al. Ethanol embolotherapy for the management of refractory chronic skin ulcers caused by arteriovenous malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(1):107-113. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2017.09.013

7 Holman E. The physiology of an arteriovenous fistula. Am J Surg. 1955;89(6):1101-1108. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(55)90471-2

8 Yakes WF. Endovascular management of high-flow arteriovenous malformations. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2004;21(1):49-58. doi:10.1055/s-2004-831405

9 Corona-Rodarte E, Cano-Aguilar LE, Baldassarri-Ortego LF, Tosti A, Asz-Sigall D. Pressure alopecias: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90(1):125-132. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.07.009

10 Ünlü Ç, de Vries JPPM. Ischaemic scalp ulceration and hair loss. The Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1375. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60929-6

11 Gilbert P, Dubois J, Giroux MF, Soulez G. New treatment approaches to arteriovenous malformations. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2017;34(3):258-271. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1604299

12 Thiex R, Wu I, Mulliken JB, Greene AK, Rahbar R, Orbach DB. Safety and clinical efficacy of Onyx for embolization of extracranial head and neck vascular anomalies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(6):1082-1086. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2439

13 Bauer AM, Bain MD, Rasmussen PA. Onyx resorbtion with AVM recanalization after complete AVM obliteration. Interv Neuroradiol. 2015;21(3):351-356. doi:10.1177/1591019915581985

14 Wang D, Su L, Fan X. Cardiovascular collapse and disseminated intravascular coagulation as complications of ethanol embolization of arteriovenous malformations in the upper lip: case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72(2):346-351. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2013.07.036

15 Wen CS, Lin SM, Chen Y, Chen JC, Wang YH, Tseng SH. Radiation-induced temporary alopecia after embolization of cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2003;105(3):215-217. doi:10.1016/s0303-8467(03)00007-6