Recurrent Martorell Ulcer in a Patient With Hypertension: A Therapeutic Success With Pentoxifylline

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Martorell ulcer is a rare skin condition that occurs in individuals with a history of long-standing uncontrolled hypertension. Martorell ulcer is often misdiagnosed on initial evaluation. Treatment primarily consists of tight pharmaceutical control of blood pressure and skin grafting. These treatments have high rates of success and often result in complete healing of the ulcer. Case Report. A 68-year-old female with Martorell ulcer on the posterolateral aspect of the left lower limb was unable to undergo either of the aforementioned primary treatments because of a complicated history of cerebral hypoperfusion secondary to multiple strokes that necessitated maintaining her blood pressure at a higher than normal range. After little success with local wound care, the patient was placed on pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day. Complete healing of the Martorell ulcer was observed, and weaning from pentoxifylline occurred over the course of 28 days. Five months later, the patient presented with recurrence of Martorell ulcer, this time on the contralateral lower limb. Prompt treatment with pentoxifylline was implemented, and the ulcer was completely healed in 29 days. Conclusion. This unique case highlights pentoxifylline as a potentially effective alternative treatment for Martorell ulcer in patients who are unable to undergo first-line treatments. The reproducibility of healing on recurrence in this case further supports consideration of this medication in select patients.

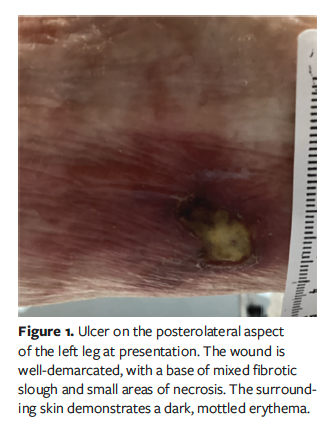

Martorell hypertensive ischemic leg ulcer is an underappreciated and often misdiagnosed clinical entity that can pose a diagnostic challenge to those unfamiliar with its presentation. These ulcers occur predominantly in older female patients with uncontrolled hypertension (HTN) and present as an exquisitely painful, well-demarcated lesion with purple-reddish edges and a mixed fibrinous and necrotic base with surrounding livedo racemosa.1 The anatomic location on the posterolateral lower leg is a defining characteristic of Martorell ulcer, with 52% of cases presenting bilaterally.2-4 All patients with Martorell ulcer have a history of HTN, and many also have type 2 diabetes mellitus and/or a high burden of cardiovascular disease, including smoking history, peripheral arterial disease, or history of ischemic stroke.1

Accurate diagnosis is crucial because other similar manifestations (eg, pyoderma gangrenosum) are treated with immunosuppression, which comes with risks to the patient.2 Biopsies of Martorell ulcer can show cutaneous calcific arteriolosclerosis; however, this finding has been shown to be nonspecific.5 Many biopsies of these lesions are taken too superficial, resulting in inconclusive biopsy results that can confound the diagnosis.6 Thus, biopsy is not considered mandatory for diagnosis, but it is still recommended to rule out other etiologies, such as pyoderma gangrenosum or other vasculitides. The clinical characteristics of Martorell ulcer can overlap with those of other conditions stemming from impaired microcirculation, such as livedoid vasculopathy and calciphylaxis, hindering prompt identification and treatment.7

Accurate diagnosis of Martorell ulcer is largely based on patient history and clinical presentation.7,8 First-line treatment consists of pharmaceutical antihypertensive agents because the etiology of the ulcer stems from ischemic subcutaneous arteriolosclerosis resulting from chronic HTN.9,10 Specifically, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium channel blockers are recommended, with recent literature revealing the role that calcium influx plays in pathogenesis of Martorell ulcer.10 β-Blockers have been shown to exacerbate Martorell ulcer due to an increase in peripheral resistance.11 With appropriate blood pressure control, recommended treatment next consists of surgical debridement and skin grafting, with reported ulcer healing rates over 90%.2,7 Other treatments that have been proposed in the literature include intravenous prostaglandin E1 infusions, pharmaceutical sympathectomy, wireless microcurrent stimulation, and even nanofat or adipose-

derived stromal cells.12-15

Case Report

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case with accompanying deidentified photographs. This report was exempt from institutional review board approval given its single-patient, retrospective nature. Great care was taken not to use any identifiable patient information in the preparation and presentation of this report.

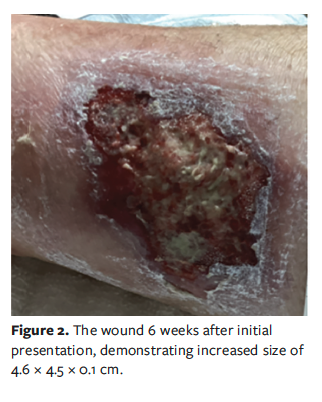

A 68-year-old female with a history of HTN, colon cancer in remission, stage 3 chronic kidney disease, cerebrovascular accident, and type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to a wound care center for evaluation of a painful wound on the posterolateral aspect of the left leg of 3 months’ duration for which she had completed multiple rounds of antibiotic treatment given by her primary care provider with no clinical improvement. The wound was well-demarcated, with a base of mixed fibrotic slough and small areas of necrosis. The surrounding skin demonstrated a dark, mottled erythema (Figure 1). On initial evaluation, the patient’s systolic pressure was 155 mm Hg and diastolic pressure was 79 mm Hg. She was initially diagnosed with a venous leg ulcer and returned for weekly light mechanical debridement because severe pain limited sharp debridement. The wound continued to increase in size over the next 6 weeks (Figure 2), leading to a more extensive workup to elucidate the etiology of this atypical presentation. Laboratory evaluation was unrevealing for underlying causes. Arterial studies revealed normal blood flow to the lower extremities. Biopsy of the site did not support vasculitis, immunobullous disease, or connective tissue disease, and there were nonspecific findings of epidermal necrosis and fibrin, and associated inflammation. Based on the clinical history, which included uncontrolled HTN, and the clinical presentation, a diagnosis of Martorell ulcer was made.

The patient had multiple cerebrovascular accidents 14 years previously, resulting in residual hemiplegia, leaving her bedbound and on home hospice care. She had another major cerebrovascular accident 5 years previously, after which she was treated with apixaban and aspirin 81 mg daily. She was not on antihypertensives, as per her neurologist’s recommendation, in order to maintain cerebral perfusion, with a systolic blood pressure goal of 140 mm Hg to 180 mm Hg. Blood pressure was consistently within this range during visits to the wound care center.

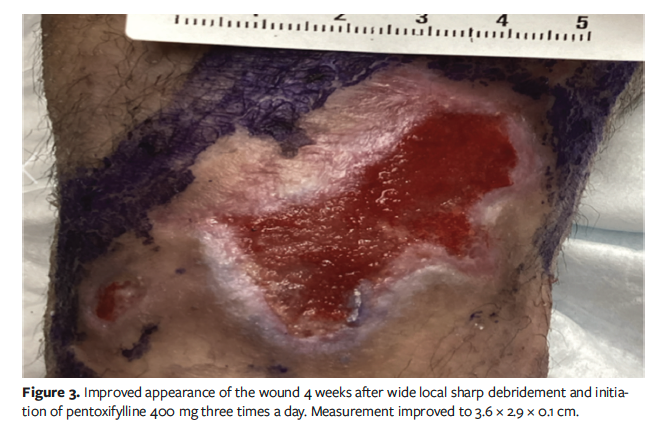

The first-line treatment for Martorell ulcer is tight blood pressure control.6,7 However, this was deemed impossible for this particular patient after discussion with her neurologist. Another treatment that has shown high rates of success is split-thickness skin grafting, which was also not considered given the patient’s poor surgical candidacy and hospice status.2 With the diagnosis of Martorell ulcer established, the patient underwent wide local sharp debridement with anesthetic block and then was prescribed pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day. She experienced rapid improvement in pain, wound size, and quality of the wound base, with rapid resolution of periwound livedo racemosa (Figure 3). The wound healed from its largest size of 8.6 cm × 4.6 cm × 0.3 cm to complete closure (Figure 4) within 3 months after initiation of pentoxifylline.

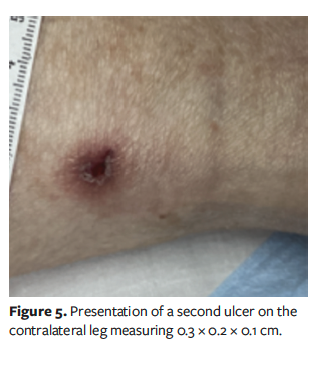

After the successful closure of the wound, the patient underwent a 28-day taper, and then pentoxifylline was discontinued. She remained ulcer-free for 5 months before presenting again with a very similar ulcer—this time on the contralateral leg (Figure 5). This posterolateral right leg ulceration was caught earlier than the ulcer on the left leg because the patient had already been established with the wound care team and her family had become vigilant participants in her hospice care. Anatomic location, near-identical contralateral wound appearance, and the patient’s persistently elevated blood pressure all suggested that this was a recurrence of Martorell ulcer. The patient was immediately restarted on pentoxifylline for treatment. Complete resolution of the Martorell ulcer was observed after only 29 days.

Because the patient was already receiving hospice care, and given the fairly rapid recurrence of the Martorell ulcer, the decision was made jointly with the patient’s family to continue pentoxifylline indefinitely to prevent recurrence in the future.

Discussion

Because the patient discussed in the current case report could not undergo pharmaceutical antihypertensive therapy and was not a candidate for surgical options such as grafting, alternate treatment methods were sought. In a case study published in 1996, Pavithran16 reported successful treatment of a Martorell ulcer using pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day, with healing occurring at 3 weeks and with no recurrence after taper. Given the unique clinical picture of the patient in the present case report, this treatment approach was implemented in her case.

Pentoxifylline is a xanthine derivative that is primarily used to treat peripheral vascular disease.17 Pentoxifylline has several effects beneficial to wound healing, including increasing oxygenation of peripheral tissues by lowering blood viscosity and reducing inflammation by repressing leukocyte function and inhibiting cytokine release. It also causes vasodilation by increasing levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in the smooth muscle of arterioles. Additionally, pentoxifylline acts as an antiplatelet agent by stimulating prostaglandin production and inhibiting phosphodiesterase.18

In clinical trials, pentoxifylline has been reported to successfully treat diffuse dermal angiomatosis, psoriasis, colitis, leishmaniasis sores, colorectal anastomosis, radiotherapy-induced ulcers, burn scars, and venous ulcers.18-21 One review of studies with a combined total of 864 patients found that pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day with compression was more effective than compression alone for healing venous leg ulcers.22 Similarly, Landry et al23 reported increased healing rates for diabetic foot ulcerations with the use of pentoxifylline. The benefits to microvascular perfusion in arteriolosclerotic tissues are of special interest for the application of pentoxifylline in the treatment of Martorell ulcer and are major contributing factors to the successful treatment of the patient presented in the current case report.

Limitations

This case report has limitations. First, the diagnosis of Martorell ulcer was made clinically, without true confirmation by histopathology, perhaps due to the superficial nature of the biopsy sample. While biopsy is not required for diagnosis and often results in nonspecific findings, the absence of histopathologic confirmation may limit diagnostic certainty. Second, the exclusion of skin substitute products in the treatment algorithm is a limitation. Although cellular and/or tissue-based products are an important therapeutic option for complex wounds, they were not pursued in this case. This decision was based on the patient’s poor candidacy for such products given her hospice status and, subsequently, the rapid clinical improvement and wound closure observed with pentoxifylline, which precluded the need to seek insurance approval for more advanced interventions. This exclusion may limit the generalizability of this case to other patients who may not be surgical candidates but who could be candidates for cellular and/or tissue-based skin substitutes. Finally, the current report is limited because it presents a single patient and cannot be used for generalization to the broader population. Despite these limitations, the reproducibility of ulcer healing on recurrence strengthens the case for pentoxifylline as a potentially effective therapeutic option in select patients with comorbidities and Martorell ulcer.

Conclusion

Although pentoxifylline has been investigated as a treatment approach for several dermatologic pathologies, most commonly venous leg ulcers, to the knowledge of the authors of the current report, the only study to date reporting the effect of pentoxifylline on Martorell ulcer is from Pavithran’s16 case report of a single patient in 1996. The patient in the current case report could not undergo the standard of care treatment of antihypertensives and skin grafting, which led to the decision to attempt management with pentoxifylline as the main treatment modality along with standard wound care. This case highlights pentoxifylline as a potentially effective treatment for Martorell ulcer in patients for whom conventional therapies are unsuitable.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Peter A. Sorensen, DPM, MHA; and Katherine Palmisano, MD

Affiliation: Ascension St. Vincent Hospital, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case with accompanying deidentified photographs. This report was exempt from institutional review board approval because of its single-patient, retrospective nature.

Correspondence: Peter A. Sorensen, DPM, MHA, 6698 Wimbledon Dr., Zionsville, IN 46077; peter.sorensen@ascension.org

Manuscript Accepted: September 8, 2025