Challenges in Cadaveric Skin Graft Survival in Organ Transplant Recipients on Immunosuppressive Regimens: A Case Report

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Complex wound management in solid organ transplant recipients presents several challenges due to impaired tissue healing resulting from chronic immunosuppressive therapy. Although some studies suggest prolonged cadaveric skin graft survival in appropriately selected immunosuppressed patients, the long-term efficacy of this approach remains unclear. The cases presented in this report describe 2 solid organ transplant recipients who experienced delayed failure of cadaveric skin grafts, highlighting the potential role of alternative wound management strategies over traditional autologous split-thickness skin grafting (STSG). Case Report. A 59-year-old male with end-stage renal and liver disease who underwent a liver-kidney transplant 3 months prior presented with a hematoma and overlying skin necrosis to his lower extremity. After serial debridements, a 25 cm × 9 cm cadaveric skin graft was applied along with negative pressure wound therapy. Despite initial adherence, the allograft subsequently failed by 4 weeks post-procedure. Similarly, a 62-year-old male with a history of diabetes-related renal disease and liver-kidney transplant 6 years prior presented with a necrotizing soft tissue infection to his lower extremity. After serial debridements, a 28 cm × 12 cm cadaveric graft was applied. The allograft initially adhered, but it gradually disintegrated by 8 weeks post-procedure. During close clinical follow-up, both patients declined subsequent STSG in favor of continued local wound care. Conclusion. These cases underscore the unpredictable long-term efficacy of cadaveric skin grafting in chronically immunosuppressed patients, emphasizing the need for extended follow-up and improved wound healing strategies in this patient population.

Introduction

In 1881, John Girdner first described the use of cadaveric skin to cover burn wounds.1 Since then, cadaveric skin grafting has become a cornerstone of complex wound management. These allografts promote wound healing by serving as an extracellular matrix scaffold that stimulates cell migration, leading to neodermis formation.2 This process provides biological wound coverage, while reducing fluid, protein, and electrolyte loss and preparing the wound bed for definitive reconstruction with an autologous skin graft.2 Human skin allografts are particularly useful when patients lack sufficient healthy donor skin for autografting or require a viable wound bed before reconstruction.

Although cadaveric skin grafts are often used as temporary biological dressings, their role in promoting wound healing in chronically immunosuppressed patients remains poorly understood. Following grafting, allogeneic skin grafts trigger a strong host immune response, primarily mediated by recipient T lymphocytes, activating an inflammatory cascade that ultimately leads to graft rejection.3,4 Even when transplanted over fully excised burn wounds, allogeneic skin grafts are typically rejected within 3 to 4 weeks.4-6

Emerging evidence suggests that chronic immunosuppression may prolong skin allograft survival in animal models.7-10 However, clinical data supporting its ability to extend allograft viability by modulating the host immune response and reducing rejection risk remain limited to clinical reports from single institutions.11-17 While some reports suggest prolonged cadaveric skin graft survival in immunosuppressed patients, long-term efficacy of this approach remains unclear.18,19

The current case report presents 2 patients on chronic immunosuppressive agents after solid organ transplantation who experienced delayed skin allograft failure.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 59-year-old male presented to the authors’ clinic for evaluation of a left lower extremity wound that developed after he struck his leg against a piece of furniture. His medical history included Bell’s palsy, hypertension, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation on therapeutic anticoagulation, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and end-stage liver and kidney disease. Three months prior to presentation, he had undergone liver and kidney transplantation and was since appropriately maintained on immunosuppressive therapy. His maintenance immunosuppression regimen included tacrolimus 4 mg twice daily and mycophenolic acid 360 mg twice daily.

On examination, the affected extremity had a large hematoma with overlying skin necrosis (Figure 1A). He subsequently underwent 3 separate procedures for complete hematoma evacuation and debridement of necrotic skin. The resulting wound was managed with negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), and 1 month later, examination revealed a well-granulated wound bed (Figure 1B). Given the patient’s significant comorbidities, including the need for long-term immunosuppression, the risks and benefits of skin autograft versus allograft application were discussed with him. He elected to proceed with application of a cadaveric skin graft.

Intraoperatively, the wound bed exhibited excellent granulation tissue and improved contour. Cryopreserved cadaveric skin (PureSkin; AlloSource) was thawed per manufacturer instructions, applied to the wound, and secured with chromic sutures (Figure 1C). The area of the cadaveric skin graft was approximately 200 cm². At the case’s conclusion, the wound measured 25 cm × 9 cm × 0.5 cm, and NPWT was continued postoperatively.

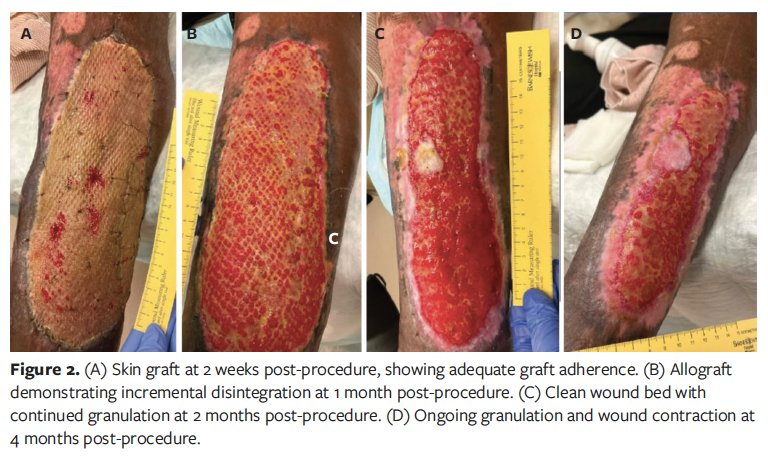

Postoperatively, the patient was followed regularly in the outpatient wound care clinic while remaining on his immunosuppression and anticoagulation regimens, with frequent medical evaluations by the organ transplant service and his primary care physician. At his 2-week follow-up visit, the cadaveric skin graft had adhered well, and the wound demonstrated healthy pink granulation tissue throughout the graft interstices (Figure 2A). However, in the following weeks the graft was incrementally rejected. At 1 month post-procedure, although the wound bed remained clean and continued to granulate well, the cadaveric skin graft had failed to adhere (Figure 2B). The possibility of application of a split-thickness skin graft (STSG) was discussed at multiple visits; however, the patient was hesitant to proceed with another operation, particularly one requiring a donor site. Consequently, he opted for continued local wound care. His wound remains on a slow healing trajectory by secondary intention (Figure 2C, 2D).

Patient 2

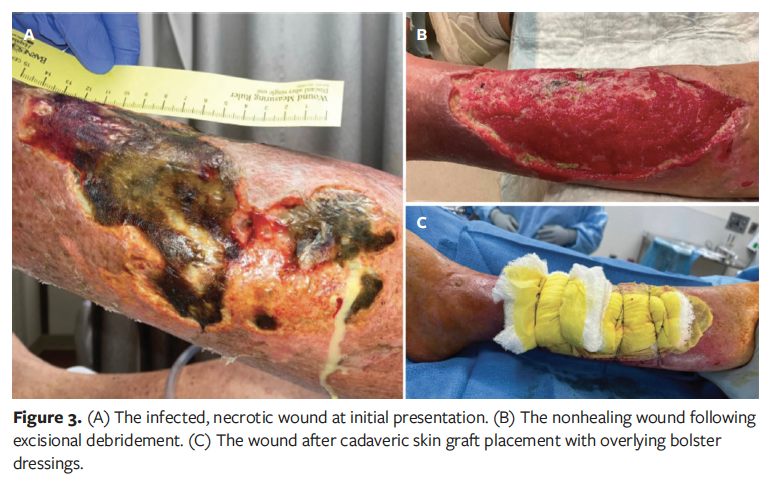

A 62-year-old male was transferred for acute management of an infected, necrotic left lower extremity wound (Figure 3A). His medical history included hypertension, T2DM, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and end-stage liver and kidney disease requiring a liver and kidney transplant 6 years prior. On examination, the wound was covered with eschar and had a small amount of foul-smelling purulent drainage. The patient was taken to the operating room for incision and drainage with excisional debridement of the eschar. Post-debridement, the wound measured 24 cm × 10 cm × 1 cm and wound cultures grew group B Streptococcus.

One month later, the patient was evaluated in the clinic and was deemed a suitable candidate for cadaveric skin graft application to facilitate ongoing soft tissue regeneration (Figure 3B). His maintenance immunosuppression regimen at that time included tacrolimus extended-release formulation 1 mg daily, mycophenolate mofetil 360 mg twice daily, and prednisone 5 mg daily. Shortly thereafter, the patient underwent further excisional debridement and application of a cadaveric skin graft. The same type of cryopreserved cadaveric allograft used for patient 1 was thawed and applied to the wound. The allograft was secured to the skin edges with staples and sutures. The area of the cadaveric skin graft was approximately 400 cm2. A bolster was then sutured to the skin to improve graft apposition (Figure 3C). At the procedure’s conclusion, the wound measured 28 cm × 12 cm.

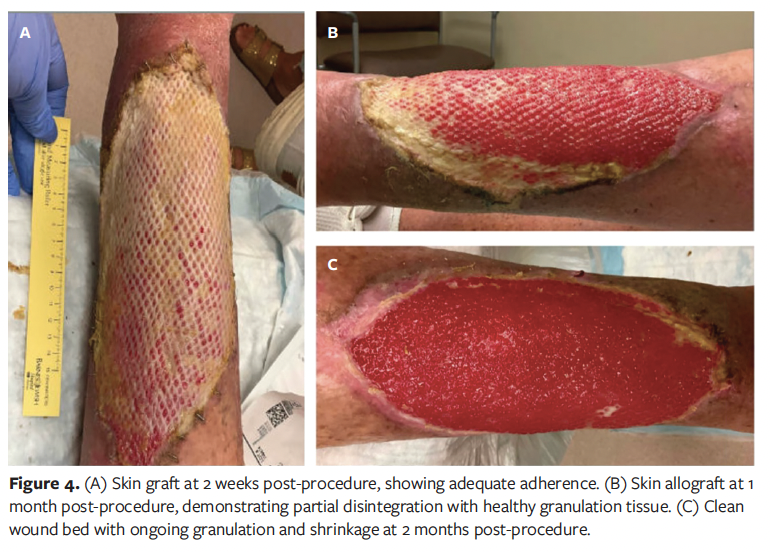

At the 2-week follow-up visit, the skin allograft had adhered well, and granulation tissue was present throughout the wound bed (Figure 4A). At 1 month post-procedure, healthy pink granulation tissue had continued to proliferate from the wound edges, and a clean eschar had formed at one margin (Figure 4B). The upper third of the wound was entirely beefy red/pink, while the lower third retained some adherent yellow cadaveric graft, which was supporting new skin and granulation growth. The patient reported no pain or discomfort and remained active, walking and performing household tasks.

By 2 months post-procedure, the cadaveric skin graft had largely disintegrated, but the wound remained healthy in appearance and continued to shrink in size (Figure 4C). Given the wound dimensions, complete closure was deemed unlikely without further intervention. The option to proceed with application of a STSG was discussed with the patient and his family. However, they preferred to continue with local wound care, with plans to reassess the need for STSG in the future. Unfortunately, the patient subsequently died from pulmonary disease nearly 3 months after the skin graft procedure, preventing further follow-up.

Discussion

Managing complex wounds in patients on chronic immunosuppression presents unique challenges. These issues were underscored in an 8-year, single-center review by Abu El Hawa et al20 of solid organ transplant recipients with extremity wounds requiring surgical intervention, which demonstrated high rates of failed minor amputations and frequent progression to major amputation. In non-immunosuppressed patients, a staged approach using cadaveric skin grafts followed by STSG has been shown to be an effective strategy for managing complex wounds of various etiologies.2 Cadaveric skin grafts can serve as an intermediate step in wound reconstruction by improving the quality of the wound bed through biological coverage while also allowing clinicians to evaluate the potential for successful STSG take. In a single-institution, retrospective analysis of 25 patients who underwent this treatment approach, Olivera Whyte et al2 demonstrated favorable outcomes, reporting a mean engraftment percentage of 96.6% for cadaveric skin grafts and 90.6% for subsequent STSG. Cadaveric skin grafts may be particularly advantageous for immunosuppressed patients who are at risk of recurrent or multiple wounds throughout their lifetime. By minimizing donor site morbidity, these allografts preserve autologous tissue for potential future use. However, the long-term viability of cadaveric allografts in this patient population remains uncertain.

The role of immunosuppressive therapy in prolonging allograft survival has been well documented in animal models.7,8,10,21-24 Jones et al10 investigated allograft survival in a porcine model by comparing 5 control pigs who received no immunosuppression with 9 pigs receiving daily doses of systemic tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. The immunosuppressed pigs all successfully accepted radial forelimb osteomyocutaneous flap transplants, with only 1 exhibiting mild rejection that had minimal effect on wound healing. Similarly, Lima et al7 studied the effects of FTY720, an immunosuppressive agent that reduces circulating T cells, on fully mismatched skin allografts in mice. The authors found that FTY720 administration extended graft survival from 12.6 days to 16.6 days. Although systemic immunosuppression may enhance allograft survival, it is also associated with increased toxicity risks.10 To mitigate these risks, local immunosuppressive strategies have been explored. Olariu et al8 demonstrated that high-dose intragraft tacrolimus injection on postoperative day 1 improved allograft survival in rat hind limb transplantation without causing hepatic or renal toxicity. These findings suggest that targeted application of immunosuppressive agents may offer a safer alternative to long-term systemic therapy for promoting allograft viability.

Despite promising preclinical results, clinical studies investigating skin allograft survival in immunosuppressed human subjects have yielded mixed findings.11-19 A large case series published in 2004 by Wendt et al13 examined 6 patients on standard renal transplant immunosuppressive regimens who received human skin allografts. All 6 allografts demonstrated complete initial engraftment and long-term survival. Notably, 2 patients discontinued immunosuppressive therapy after renal transplant rejection (1 after 6 weeks, the other after 5 years). In the latter case, although the allograft cells were eventually replaced by autogenous cells, acute rejection did not occur, and the graft persisted clinically. However, other studies have reported contradictory results, raising concerns about the long-term viability of skin allografts in immunosuppressed patients.18,19

In the present case report, 2 solid organ transplant recipients initially exhibited successful allograft take, but ultimately they experienced delayed graft failure despite maintaining their prescribed immunosuppressive regimens. These findings highlight the complex interplay between host immunity, immunosuppressive therapy, and skin allograft survival. In both cases, the cadaveric skin grafts provided early benefits, including reduced fluid and protein loss, infection prevention, and enhanced wound healing. However, despite initial adherence, the grafts failed to integrate long-term and were ultimately rejected within weeks. These findings suggest that although immunosuppressive therapy may prolong allograft survival in some appropriately selected patients, it does not guarantee sustained integration in all immunocompromised individuals. The variability in outcomes may be influenced by factors such as existing comorbidities, time since transplantation, and immunosuppression dosing.

Additionally, both patients in the present report declined further surgical intervention despite being offered definitive reconstruction with autologous STSG after signs of graft rejection emerged. This aligns with the authors’ institutional experience that some patients with nonhealing wounds following an unsuccessful surgical intervention often hesitate to pursue additional procedures, instead opting for ongoing local wound care. Emerging therapies, including cellular, acellular, and matrix-like products (CAMPs), are being explored as alternatives to standard STSG to reduce the need for repeated operations.25-27 Although CAMPs have demonstrated promising wound healing outcomes, further comparative studies are needed to elucidate their physiological mechanisms and clinical efficacy.26,27

Limitations

The small sample size of this case report may limit the generalizability of the authors’ findings. Additionally, variations in immunosuppressive agents and time since organ transplantation among included patients may further complicate interpretation. Larger, prospective studies are needed to better define the relationship between long-term immunosuppressant use and skin allograft survival.

Conclusion

The cases presented in this report underscore the challenges of managing complex wounds in immunocompromised patients and highlight the limitations of cadaveric skin grafting in this patient population. While prior research suggests that chronic immunosuppressive therapy may prolong skin allograft survival, this case report suggests that long-term graft integration is not always successful. Additionally, these findings emphasize the need for extended follow-up of these patients and further research exploring alternative wound healing strategies, particularly for patients who are reluctant to undergo repeat surgical procedures (eg, STSG).

Author and Publication Information

Authors: Steven Tohmasi, MD, MPHS¹; Carolyn Tsung, BA1; Ariana Naaseh, MD, MPHS1; Jennifer Yu, MD, MPHS2; John P. Kirby, MD1; and Lindsay M. Kranker, MD1

Affiliations: 1Section of Acute and Critical Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA; 2Section of Abdominal Transplant Surgery, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA

Acknowledgments: This work was presented at the Poster Session of the 2025 Symposium on Advanced Wound Care (SAWC) Spring Meeting | Wound Healing Society (WHS) Annual Meeting in Grapevine, TX, April 30-May 4, 2025.

Authorship Contributions: All authors substantially contributed to the work’s conception, manuscript drafting, and revision for intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the article prior to publication.

Disclosure: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. S.T. and A.N. received salary support via the Washington University School of Medicine Surgical Oncology Basic Science and Translational Research Training Program grant T32CA009621 from the National Cancer Institute. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute. The other authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval: This case report was deemed exempt by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board. Informed written consent was obtained from both patients and/or their families before publication of their cases.

Correspondence: Lindsay M. Kranker, MD; Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S. Euclid Ave, MSC-8109-0043-1160, St. Louis, MO 63110; kranker@wustl.edu

Manuscript Accepted: September 22, 2025

References

1. Girdner JH. Skin-grafting with grafts taken from the dead subject. Medical Record (1866-1922). 1881;20(5):119.

2. Olivera Whyte LM, Izquierdo ME, Gutiérrez Pachón DM, Rodríguez JA, Prezzavento GE. Versatility in the use of cadaveric skin grafts for wound management. Wounds. 2024;36(9):303-311. doi:10.25270/wnds/24004

3. Marino J, Paster J, Benichou G. Allorecognition by T lymphocytes and allograft rejection. Front Immunol. 2016;7:582. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00582

4. Gardner CR. The pharmacology of immunosuppressant drugs in skin transplant rejection in mice and other rodents. Gen Pharmacol. 1995;26(2):245-271. doi:10.1016/0306-3623(94)00113-2

5. Bravo D, Rigley TH, Gibran N, Strong DM,

Newman-Gage H. Effect of storage and preservation methods on viability in transplantable human skin allografts. Burns. 2000;26(4):367-378. doi:10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00169-2

6. Hansbrough JF, Mozingo DW, Kealey GP, Davis M, Gidner A, Gentzkow GD. Clinical trials of a biosynthetic temporary skin replacement, Dermagraft-Transitional Covering, compared with cryopreserved human cadaver skin for temporary coverage of excised burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1997;18(1 Pt 1):43-51. doi:10.1097/00004630-199701000-00008

7. Lima RSM, Nogueira-Martins MF, Silva HT Jr, Pestana JOM, Bueno V. FTY720 treatment prolongs skin graft survival in a completely incompatible strain combination. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(4):1015-1017. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.052

8. Olariu R, Denoyelle J, Leclère FM, et al. Intra-graft injection of tacrolimus promotes survival of vascularized composite allotransplantation. J Surg Res. 2017;218:49-57. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.046

9. Solari MG, Washington KM, Sacks JM, et al. Daily topical tacrolimus therapy prevents skin rejection in a rodent hind limb allograft model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(2 Suppl):17S-25S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318191bcbd

10. Jones JW Jr, Ustüner ET, Zdichavsky M, et al. Long-term survival of an extremity composite tissue allograft with FK506-mycophenolate mofetil therapy. Surgery. 1999;126(2):384-388.

11. Vyas KS, Burns C, Ryan DT, Wong L. Prolonged allograft survival in a patient with chronic immunosuppression: a case report and systematic review. Wounds. 2017;29(6):159-162.

12. Mindikoğlu AN, Cetinkale O. Prolonged allograft survival in a patient with extensive burns using cyclosporin. Burns. 1993;19(1):70-72. doi:10.1016/0305-4179(93)90105-h

13. Wendt JR, Ulich T, Rao PN. Long-term survival of human skin allografts in patients with immunosuppression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(5):1347-1354. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000112741.11726.91

14. Pomahac B, Garcia JA, Lazar AJ, Tilney N, Orgill DP. The skin allograft revisited: a potentially permanent wound coverage option in the critically ill patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(6):1755-1758. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a65b1b

15. Matsumine H, Morioka K, Kawate H, et al. Successful surgical treatment of severe burn in an immunocompromised patient under long-term treatment for frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32(3):e110. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e318217fa88

16. Burke JF, May JW Jr, Albright N, Quinby WC, Russell PS. Temporary skin transplantation and immunosuppression for extensive burns. N Engl J Med. 1974;290(5):269-271. doi:10.1056/nejm197401312900509

17. Hardy K, Mullens C, McCulloch I, Manders EK, Ueno C. Prolonged allograft survival in immunocompromised patients. ACS Case Reviews in Surgery. 2020;2(5):22–27.

18. Eldad A, Benmeir P, Weinberg A, et al. Cyclosporin A treatment failed to extend skin allograft survival in two burn patients. Burns. 1994;20(3):262-264. doi:10.1016/0305-4179(94)90197-x

19. Delikonstantinou I, Philp B, Kamel D, Barnes D, Dziewulski P. A major burn injury in a liver transplant patient. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2016;29(3):206-208.

20. Abu El Hawa AA, Bekeny JC, Dekker PK, et al. Surgical management of lower extremity wounds in the solid organ transplant patient population: surgeon beware. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2022;11(1):10-18. doi:10.1089/wound.2020.1380

21. Ding Q, Mohib K, Kuchroo VK, Rothstein DM. TIM-4 identifies IFN-γ-expressing proinflammatory B effector 1 cells that promote tumor and allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2017;199(7):2585-2595. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1602107

22. Silva FR, Silva LBL, Cury PM, Burdmann EA, Bueno V. FTY720 in combination with cyclosporine—an analysis of skin allograft survival and renal function. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6(13-14):1911-1918. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2006.07.014

23. Lopes CT, Gallo AP, Palma PVB, Cury PM, Bueno V. Skin allograft survival and analysis of renal parameters after FTY720 + tacrolimus treatment in mice. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(3):856-860. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.02.051

24. Inamura N, Nakahara K, Kino T, et al. Prolongation of skin allograft survival in rats by a novel immunosuppressive agent, FK 506. Transplantation. 1988;45(1):206-209. doi:10.1097/00007890-198801000-00042

25. Liden BA, Liu T, Regulski M, et al. A multicenter retrospective study comparing a polylactic acid CAMP with intact fish skin graft or a collagen dressing in the management of diabetic foot ulcers and venous leg ulcers. Wounds. 2024;36(9):297-302. doi:10.25270/wnds/24060

26. Wu S, Carter M, Cole W, et al. Best practice for wound repair and regeneration use of cellular, acellular and matrix-like products (CAMPs). J Wound Care. 2023;32(Sup4b):S1-S31. doi:10.12968/jowc.2023.32.Sup4b.S1

27. Nherera LM, Banerjee J. Cost effectiveness analysis for commonly used human cell and tissue products in the management of diabetic foot ulcers. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7(3):e1991.