Acid-Fast Bacilli Staining for Nonhealing Ulcers: A Case Report of Cutaneous Mycobacterium chelonae Infection

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Cutaneous infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are rare, and they can be challenging to treat, often requiring prolonged therapy with multiple antibiotics. Although recent literature challenges the idea of routine acid-fast bacilli (AFB) testing in diabetic foot infections, this report presents a case of Mycobacterium chelonae (M chelonae) infection in a patient with nonhealing ulceration. Case Report. A 64-year-old female with no history of immunocompromise and no recent surgical history presented with a rapidly growing ulceration despite appropriate antibiotic therapy based on routine aerobic culture results. After AFB cultures were obtained, she was found to have NTM infection with M chelonae, and the ulceration was healed without recurrence after treatment for 4 months with linezolid and clarithromycin. Conclusion. This case highlights the potential inoculation of M chelonae, even in immunocompetent patients without known inoculation injury, and it highlights the value of AFB cultures in patients who do not progress with standard wound care therapies and routine aerobic cultures.

Introduction

Cutaneous infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are challenging to treat, requiring multiple antibiotics for months of therapy. Wentworth et al1 evaluated the prevalence of cutaneous NTM infections and noted a 3-fold increase from January 1, 1980, to December 31, 1999, compared with January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2009; specifically, there was an increase in the number of infections due to Mycobacterium chelonae (M chelonae) and Mycobacterium abscessus. Most mycobacteria require prolonged incubation, and there is a low incidence of positive cultures from biopsy samples in diabetic foot ulcerations and infections.2 Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining and culture is usually not performed as a part of routine practice.

M chelonae can cause cutaneous infections and can infect immunocompetent patients.3 Typically, it presents after inoculation, occurring after medical procedures; it is not uncommon to find M chelonae in health care settings, because it resists standard decontamination processes.4

This case report describes a patient with a chronic foot ulcer who was found to have M chelonae infection after lack of healing with standard of care.

Case Report

A 64-year-old female presented with an increasingly enlarging wound on the medial aspect of her left heel. She noted no clear etiology for the wound, denying any accident, injury, trauma, or shoe irritation. She had been self-managing the wound with conservative treatments, including topical antibiotic and dry sterile dressings for several weeks without improvement. Past medical history was significant for mild peripheral arterial disease (PAD) with previous stent placement of bilateral iliac arteries (right toe brachial index [TBI] of 0.87 and ankle-brachial index [ABI] of 0.96, and left TBI of 0.65 and ABI of 0.95, with triphasic flow noted to bilateral dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulse) and type 2 diabetes mellitus, with the most recent A1c of 5.5%. She was a former 22.5 pack per year smoker and had quit smoking 10 years prior to the onset of this wound. Her diabetes was treated with dapagliflozin 10 mg daily and dulaglutide 0.75 mg once weekly. She was medically managed for her PAD with clopidogrel 75 mg daily, rosuvastatin 40 mg daily, and cilostazol 50 mg twice daily.

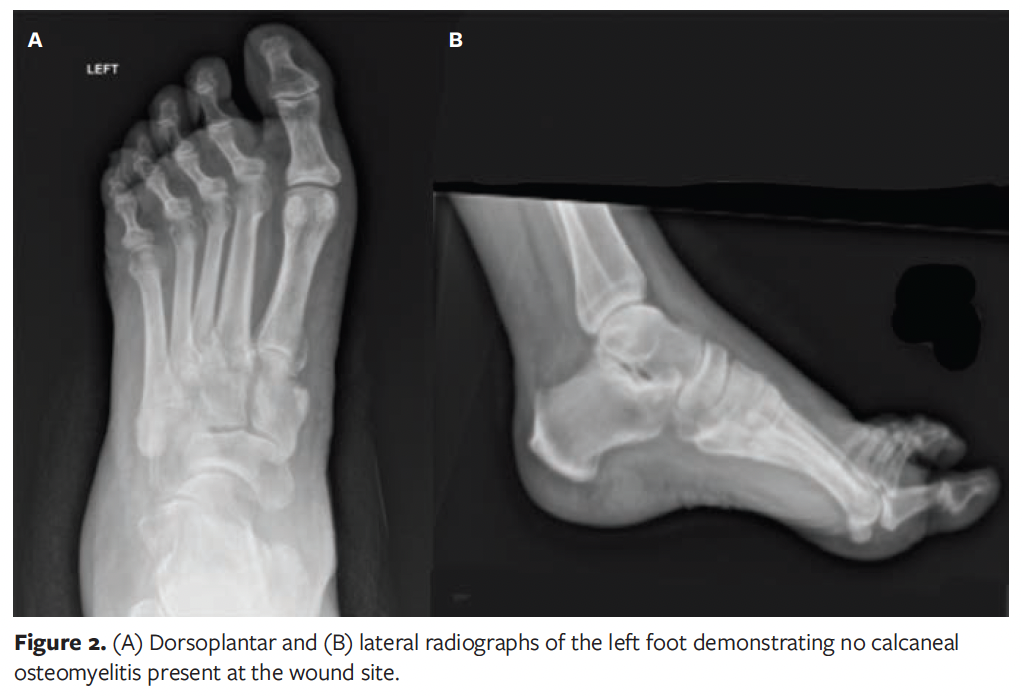

At the time of presentation to the authors of this case report, patient had been presenting on a weekly basis to an outside podiatrist for approximately 8 weeks (Figure 1). In addition to receiving care from the outpatient podiatrist, the patient had been following up intermittently with her vascular surgeon, who believed the patient did not need further surgical intervention and deemed her to have “mild arterial disease” at the time of this wound. The patient’s treatment included routine debridement, application of silver-enhanced alginate (ie, silver alginate), and off-loading with a tall controlled ankle motion boot/removable cast walker. During this time, the patient was monitored for signs of osteomyelitis to the left calcaneus with serial foot radiographs and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which showed no evidence of calcaneal osteomyelitis (Figure 2). The patient was also monitored for signs of worsening arterial status to the lower extremities, with no status change during the progression of this wound. She was deemed medically optimized from a vascular surgery standpoint.

Of note, prior to hospitalization with the authors of the present study, there were 3 inpatient hospitalizations due to increased pain, erythema, and swelling during the treatment course. Detailed social and medical history were reviewed. The patient reported no recent travel or sick contacts. She did report a bout of significant depression during which she neglected self-care and household chores, resulting in overall poor housing conditions.

During the first hospitalization, the patient was placed on empiric intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam for 3 days and then was transitioned to oral azithromycin for 14 days in the outpatient setting. Although this antibiotic regimen appeared to improve some of her infection symptoms, such as erythema and swelling, during several follow-up appointments the patient’s medial foot wound continued to enlarge, and a new wound developed on the lateral side of her foot. During this follow-up course, MRI had ruled out calcaneal osteomyelitis, and deep soft tissue cultures were obtained. Those cultures were sent for aerobic and anaerobic analysis and showed “no growth.”

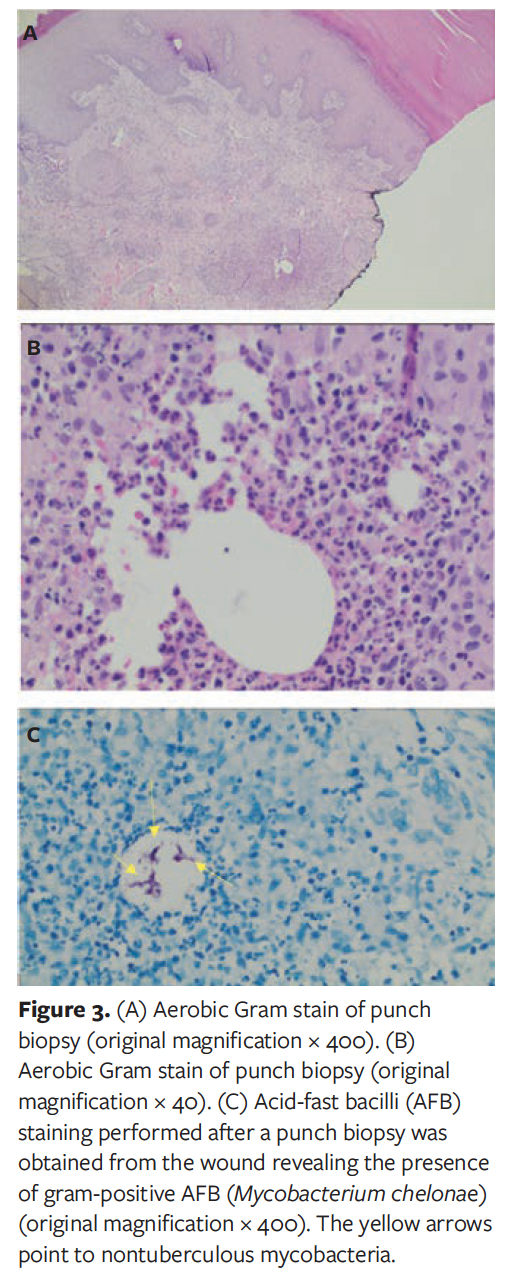

Following her second hospitalization, the patient received several intravenous antibiotics—initially vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam. During this hospitalization, a repeat deep soft tissue culture was sent for analysis and revealed “possible actinomyces.” Due to this finding, the patient was transitioned to intravenous penicillin daily via a peripherally inserted catheter line for 6 weeks in the outpatient setting. However, even with this antibiotic regimen, her wounds continued to increase in size for 3 weeks to 4 weeks and then stabilized. Because these wounds increased in size over the month-long period, and because they did not heal over an 8-week period, it was suggested that the patient be readmitted to the hospital for further workup, including a punch biopsy, possibly followed by discharge to subacute rehabilitation to help aid in strict non-weight bearing status to the left lower extremity. The need for a punch biopsy was secondary to other concerning diagnoses, including Marjolin ulcer or squamous cell carcinoma. During the patient’s third hospitalization, a tissue culture from a 3-mm punch biopsy was sent, along with tissue for microbiology for aerobic, anaerobic, fungal, and AFB cultures. AFB smears revealed the presence of AFB (Figure 3). The patient was then transferred to a tertiary hospital for further antibiotic and wound care recommendations.

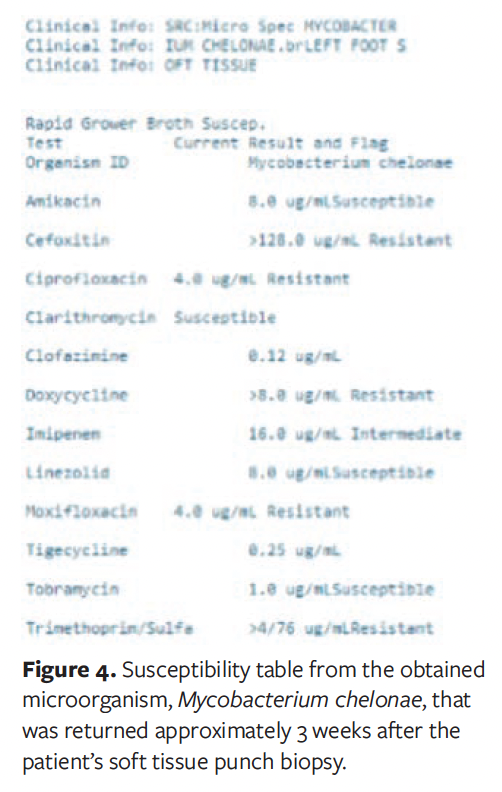

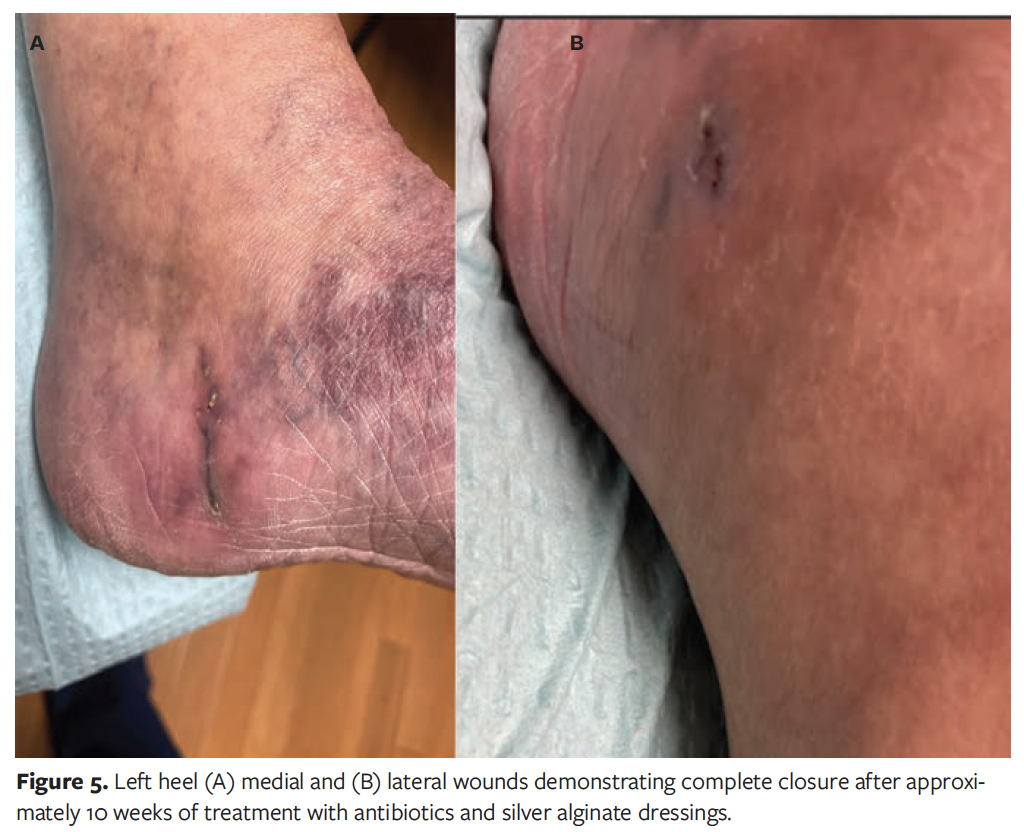

At transfer, the patient’s history was reviewed, again revealing no recent surgeries and no changes to her daily routine, including no recent travels outside of Canada and the United States or unique sick contacts. The patient had stated that she was in good health, with the only immunosuppressive condition being diabetes mellitus, which was well controlled, with A1c of 5.5%. Further workup was initiated, including an interferon gamma release assay for tuberculosis, which was negative. Her chest radiograph showed no pathology. AFB culture from previously obtained foot biopsy grew M chelonae after 10 days; susceptibility testing results were returned after 14 more days (Figure 4). After consultation with infectious diseases specialists, a 4-month course of oral linezolid 600 mg daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily was recommended, as well as silver alginate dressing changes. After 10 weeks of this treatment regimen, the patient’s wounds healed (Figure 5).

Discussion

M chelonae often causes extrapulmonary infections. In the case of the patient in the present report, 2 questions arose: How was this microbe transmitted to the patient? How did it evade detection for so long? Typically, M chelonae presents as a localized skin and soft tissue infection after a procedure or catheter infection. Additionally, this microbe can be found in aquatic or soil environments. While the patient discussed herein initially presented with this wound in the late summer months, she denied walking barefoot in the garden, as well as any sick contacts in the hospital.

For this patient, routine bacterial culture from a deep tissue swab did not yield the correct microbe of etiology, instead identifying it as a possible actinomyces or gram-negative rod infection. Identification of M chelonae requires AFB culture techniques and usually requires an average 15-day incubation period. Other AFB can take up to 6 to 8 weeks to grow in culture.

There is also a question of whether every nonhealing wound requires evaluation for AFB infection. Several recent studies have evaluated positive results from AFB cultures from soft tissue and bone samples over 5- and 10-year periods, and found a less than 1% positive rate.2,5,6 Castellino et al2 recently sought to determine the value of sending all cultures for AFB stains at their institution. Over a 3-year period, AFB stains were performed in 1449 soft tissue cultures, resulting in only 2 positive results, for an incidence of 0.0014%. On average, the cost of each AFB culture was $78.2 While obtaining routine AFB cultures for every wound is not economical or clinically necessary, the case described in the present report supports previous recommendations suggesting comprehensive wound reevaluation and consideration of wound biopsy within 30 days of standard therapy and lack of progression toward healing.7 On a re-biopsy, it may be appropriate to specifically order AFB cultures, because these organisms require incubation methods different from those for bacterial or fungal organisms.

For patients with soft tissue infections with M chelonae, it is fortunate that this microbe rarely progresses to osteomyelitis in patients who are not on active chemotherapy and in those who have not received a transplant. Treatment can take 6 months or longer and requires a combination of antibiotics to prevent development of antibiotic resistance. Of reported treatment methods, infection was resolved in 87.5% and 75% of patients treated with intravenous aminoglycosides or clarithromycin respectively in 1 study; however, toxicity must be taken into consideration, especially for aminoglycosides.7

In the case described in the present report, after susceptibility testing results were returned the patient was treated with a combination of linezolid and clarithromycin with close laboratory monitoring. The decision to treat with oral linezolid and clarithromycin was multifactorial. First, linezolid has excellent activity and tissue penetration in extrapulmonary NTM.8 Second, another study found that when clarithromycin was used to treat M chelonae, ulcer healing occurred in 81.8% of patients within 6 months, with no evidence of relapse or positive AFB cultures on routine follow-up.9 Finally, although linezolid is typically prescribed to be taken twice per day, due to its side effect profile, the length of treatment required for NTM infections, and clinical experience, the choice was made to prescribe it to be taken once per day, which is also in accordance with guidelines.10 This combination of therapy was successful, and the patient’s wounds healed after about 10 weeks.

In addition, it is often important to choose the correct wound care dressings for appropriate wound management, because even with correct antibiotics, wound care dressing can be a barrier to wound healing. In the present case, during the patient’s final hospitalization there was a focus on the best topical wound care product to assist with wound healing after appropriate oral antibiotics were chosen. A review of the literature on this topic revealed a paucity of recommendations for topical treatments, often only focused on oral antibiotic treatment. One study investigated the effectiveness of silver’s bactericidal properties and found that it achieved 100% bactericidal activity against both rapidly and slowly growing mycobacteria for up to 7 days.11 Given that both wounds in the present case were shallow and the primary evidence supported the use of silver coupled with the wounds’ characteristic of excessive drainage, silver alginate was selected as the most suitable product for treatment.

Limitations

This present study is limited in that it only reports on a single case that presented to a tertiary academic hospital. A further limitation is that continuity of care was interrupted as the patient required input from the academic institution, but stated she lived too far away from this institution to follow long care. Due to this, serial imaging and workup could not be followed as it would be in standard case reports.

Conclusion

While the incidence of positive AFB cultures from soft tissue samples is low, NTM infections still do occur in patients with foot wounds. In the patient described in this report, if AFB cultures had not been obtained, her wounds would not have been treated appropriately and she may have progressed to calcaneal osteomyelitis, with consequent detrimental effects on her mobility and quality of life. It is recommended to send AFB cultures as part of the workup for nonhealing wounds that have been unresponsive to 4 weeks to 6 weeks of standard therapy.

Author and Public Information

Authors: Stephanie Behme, DPM1; Shiwei Zhou, MD1; Andrew Brown, DPM2; and Gary M. Rothenberg, DPM, CDCES, CWS1

Affiliations: 1University of Michigan, Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; 2Henry Ford Genesys Hospital, Grand Blanc, MI, USA

Disclosure: The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or other conflicts of interests.

Ethical Approval: Written and informed consent as well as photo consent was obtained for publication of the case report and associated images.

Correspondence: Stephanie Behme, DPM; University of Michigan Medical School, 24 Frank Lloyd Wright Drive, Lobby C, Ann Arbor, MI 48106; behmest@med.umich.edu

Manuscript Accepted: June 11, 2025

References

1. Wentworth AB, Drage LA, Wengenack NL, Wilson JW, Lohse CM. Increased incidence of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, 1980 to 2009: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(1):38-45. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.06.029

2. Castellino LM, McCormick-Baw C, Coye T, et al. Limited clinical utility of routine mycobacterial cultures for the management of diabetic foot infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(11):ofad558. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad558

3. Dumic I, Lutwick L. Successful treatment of rapid growing mycobacterial infections with source control alone: case series. IDCases. 2021;26:e01332. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01332

4. Cusumano LR, Tran V, Tlamsa A, et al. Rapidly growing Mycobacterium infections after cosmetic surgery in medical tourists: the Bronx experience and a review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;63:1-6. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2017.07.022

5. Tokarski AT, O'Neil J, Deirmengian CA,

Ferguson J, Deirmengian GK. The routine use of atypical cultures in presumed aseptic revisions is unnecessary [published correction appears in Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(6):2043]. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(10):3171-3177. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2917-7

6. Shah M, Relhan N, Kuriyan AE, et al. Endophthalmitis caused by nontuberculous mycobacterium: clinical features, antimicrobial susceptibilities, and treatment outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;168:150-156. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2016.03.035

7. Sheehan P, Jones P, Caselli A, Giurini JM, Veves A. Percent change in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4-week period is a robust predictor of complete healing in a 12-week prospective trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1879-1882. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.6.1879

8. Wallace RJ Jr, Brown-Elliott BA, Ward SC, Crist CJ, Mann LB, Wilson RW. Activities of linezolid against rapidly growing mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(3):764-767. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.3.764-767.2001

9. Wallace RJ Jr, Tanner D, Brennan PJ, Brown BA. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for cutaneous (disseminated) infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(6):482-486. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00006

10. Daley CL, Iaccarino JM, Lange C, et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1):2000535. doi:10.1183/13993003.00535-2020

11. Bowler PG, Welsby S, Towers V. In vitro antimicrobial efficacy of a silver-containing wound dressing against mycobacteria associated with atypical skin ulcers. Wounds. 2013;25(8):225-230.