Fluorescein Dye-Assisted Tangential Excision and Skin Grafting in Hand Burns: Achieving Optimal Cosmetic and Functional Outcomes

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Burned hands require special attention and prompt treatment because of their vital functional importance. With fluorescein dye, it is possible to visualize vascular dermal layers to assist with the removal of nonviable skin through tangential excision.

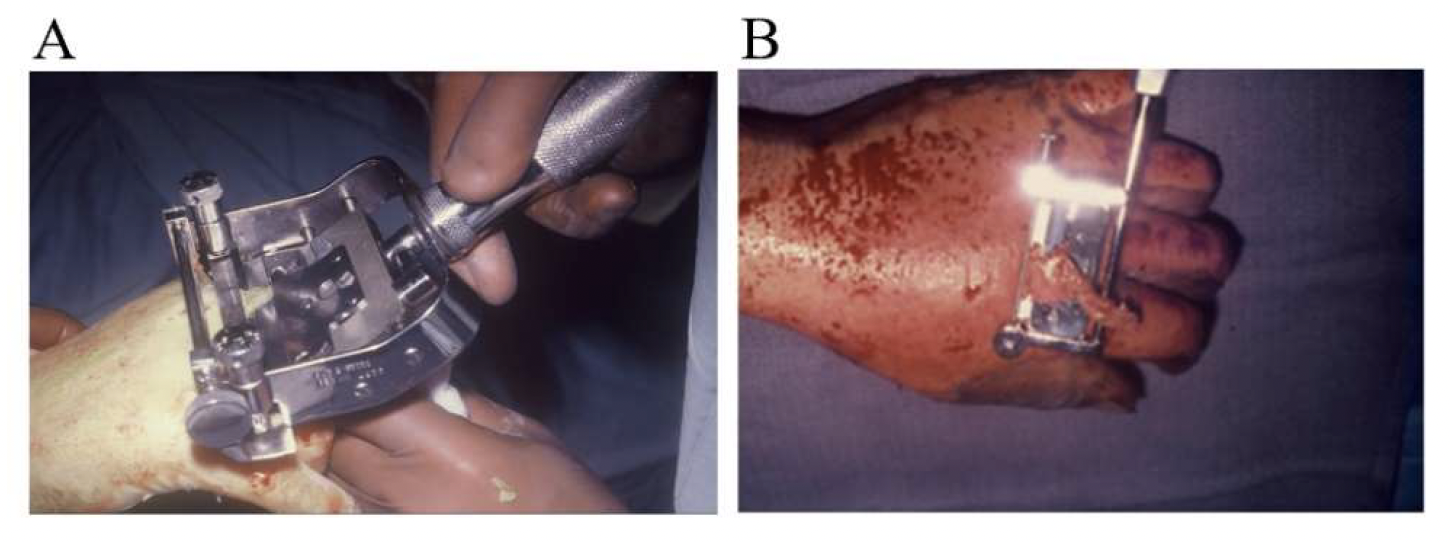

Methods. Within 24 to 48 hours after a burn, 5 mg of fluorescein dye was injected intradermally and a Wood light was used to determine burn depth. Under anesthesia, an Air Brown (Zimmer Biomet) or castroviejo dermatome and a free-hand or Humby knife was used to excise the burned skin. Split-thickness layers approximately 0.015 inches thick were removed until strong fluorescence was noted.

Results. Observation indicators were used to assess the quality of the skin graft outcomes. No cases of infection, seromas, hematomas, or contractures were seen. Additionally, patients experienced reasonable cosmetic and functional outcomes within weeks to months following grafting.

Conclusions. Excision and split-thickness skin grafting with fluorescein dye and tangential excision can achieve desirable results and restore both cosmetic and functional outcomes.

Introduction

Burns and burn-related injuries represent a significant public health problem globally, with over 11 million new cases reported each year worldwide.1 The American Burn Association estimates that, in the United States, 1.1 million burn injuries require medical attention annually, with up to 10 000 deaths due to burn-related infections.2

Hand burns in particular require special attention and prompt treatment because of the hands’ vital functional importance. These burns can result from various etiologies, including spilling hot liquids, chemical injuries, thermal injuries via flame, or electrical injuries.3 Among the most common hand burns are partial thickness (second-degree) burns, which occur when the burn extends through the epidermis and into the dermis at varying depths. These burns are often very painful, erythematous, blistered, and moist, and blanch with pressure.4 However, in cases where deeper layers of the skin are involved, blanching may be absent. With fluorescein dye, nonviable skin layers can be removed via tangential excision until viable layers are reached, as indicated by the luminescence of the fluorescein dye under a Wood’s light.

When the burn impacts only the superficial dermis, conservative treatment methods often provide satisfactory outcomes. These methods include cooling with cold water, cleansing with soap, applying topical antibacterial agents such as silver sulfadiazine, and managing pain.5-7 However, deeper burns, particularly deep second-degree burns, carry increased risks, including loss of hand function, infection leading to sepsis, hypovolemia, hypothermia, prolonged healing, and hypertrophic scarring.8-10 This report describes a technique the authors have found effective in treating deep partial-thickness (second-degree) burns.

Methods and Materials

Technique

Early tangential excision of the burned hand was performed as soon as the patient’s clinical condition stabilized, typically within 24 to 48 hours after the burn. Five mg of fluorescein dye were injected intradermally prior to surgery, and the patient was evaluated 30 to 60 minutes later for possible allergic reactions. Adults were injected with 10 mg/kg of fluorescein dye (10 mg/kg) intravenously, and children under 10 years old received 5 mg/kg. A Wood light was used 10 minutes after injection to determine whether the burn was a deep second-degree burn and to assist the surgeon in removing thin layers of skin. Fluorescence in a deeper layer indicated that a vascular dermal layer had been reached. Fine bleeding after split-thickness excision was another indicator that a perfused layer of skin had been reached.

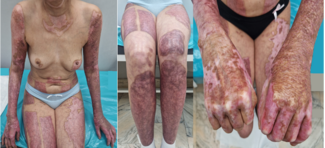

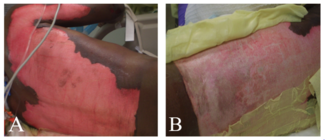

The procedure was performed under either general anesthesia or an upper extremity nerve block. Figure 1 demonstrates the hand 10 to 15 minutes after intravenous injection of the fluorescein dye, showing the absence of fluorescence. We utilized an Air Brown (Zimmer Biomet) or castroviejo dermatome (Figure 2A) for the dorsum of the hands and reserved a free-hand or Humby knife to excise burned skin from the digits (Figure 2B). Split-thickness layers of burned skin approximately 0.015 inches thick were removed until good fluorescence was noted, as shown in Figure 3. In the vast majority of deep second-degree hand burns, 1 pass of the dermatome sufficed. Thin- to medium-thickness (0.015-0.018 inches) split-thickness skin grafts were then harvested from an unburned site (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Ten to 15 minutes after intravenous injection of fluorescein dye.

Figure 2. Dorsum of the hand, utilizing an (A) Air Brown dermatome (Zimmer Biomet) or (B) Humby knife to excise the burn skin from the digits.

Figure 3. Fluorescence is noted immediately after removal of split-thickness layers of burned skin.

Figure 4. Split-thickness skin grafts harvested from an unburned site on the dorsal aspect of the wrist.

The hand was dressed with fine mesh petrolatum gauze, and a normal saline-dampened gauze dressing was applied. The hand and wrist were immobilized with a volar splint. The skin graft recipient sites were inspected 2 days after grafting, and any blood or serum collection was drained. All dressings and the splint were removed within 10 days, and gentle hand exercises were initiated. Outcome assessments were conducted through observational evaluation of the skin graft quality at 6-months postoperative (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Outcomes 6 months after surgery.

Results

In this study, 20 patients underwent tangential excision of a burned hand assisted by a fluorescein dye visualization method. The skin-graft take was estimated on a scale of 0% (total graft loss) to 100%. Areas of "no-take" were clinically assessed and defined by the percentage of surface area of rejection and exposure of deep dermal or subcutaneous tissues. Using this method, 16 of 20 (80%) patients showed 100% graft take. However, 4 of 20 (20%) patients exhibited a 5% to 10% graft loss, not due to infection or hematoma. These losses were most likely caused by areas of hypovascularity, leading to the inability to vascularize the overlying skin grafts. The partial graft loss did not affect the healing period or physical therapy. Although some degree of hypertrophic scarring was noted in the majority of patients, none resulted in contractures or functional deficits. Additionally, no cases of allergy to fluorescein dye were observed in this study. Despite this small rate of complications, all 20 patients were satisfied with their functional outcomes and their ability to return to work.

Discussion

Early excision of deep second- and third-degree burns has been well established in the burn literature.11-13 Due to the functional importance of hands, we recommend early excision of burned skin and split-thickness skin grafting with the use of fluorescein dye. The authors found that early excision minimizes common problems, including wound infection, contracture, and prolonged healing.

Other studies have evaluated the differences in outcomes between early and delayed excision and skin autografting, showing that early grafting provides significantly improved outcomes in terms of infection rates and even patient mortality, making early tangential excision one of the gold standard techniques in burn care.14-16

Fluorescent dyes, such as indocyanine green (IG), have been shown to be nontoxic, rapidly excreted into bile by the liver, and routinely used in other fields, including ophthalmology, for visualizing choroidal circulation and measuring cardiac/hepatic output.17-18 While this dye is considered extremely safe and is used widely in medicine, some rare side effects include toxic reactions, which are extremely rare and were not observed in this study.18 Additionally, other studies have reported success in using IG fluorescein dye to differentiate viable from nonviable tissue and to estimate burn depth.17,19 In fact, the use of fluorescein dye to determine viability has been well described in previous literature, including in the assessment of skin flap viability in pigs and in determining mastectomy skin-flap viability following autologous tissue reconstruction.20

The current standard for assessing the adequacy of burn excision relies on visualizing the deep dermis and detecting punctate bleeding after tangential excision.21 In functionally and cosmetically sensitive areas, such as the hands and face, debridement must be performed with greater caution to preserve critical structures. Fluorescent dye may help achieve more precise resection of nonviable tissue, potentially improving outcomes. However, in deeper burns, tangential excision may extend beyond the penetration of fluorescein dye, and its visibility can be influenced by regional circulation. Future studies should compare graft outcomes between cases assessed solely by clinical evaluation of punctate bleeding and those supplemented with fluorescein dye to determine the added value of this technique.

Limitations

The lack of a control nonfluorescence group is a limitation of this study; however, we show that both cosmetic and functional outcomes were satisfactory in all patients treated using this technique. More studies are needed to validate this technique in multiple surgical centers.

Conclusions

Early excision of burned skin and split-thickness skin grafting using fluorescein dye and a Wood light can achieve desirable cosmetic and functional outcomes within a reasonable time. Further studies are needed to better elucidate the role of fluorescent dyes in early tangential excision and split-thickness skin grafting for burn repair, particularly in extremities such as the hands, which serve vital functions.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Dylan Singh, MD1; Justin H. Wong, BS1; Alan A. Parsa, MD1; Fereydoun D. Parsa, MD, FACS2

Affiliations: 1Department of Medicine, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii; 2Plastic Surgery Division, Department of Surgery, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii

Correspondence: Fereydoun Don Parsa, MD FACS, 1329 Lusitana Street, Suite 807, Honolulu, HI 96813, USA. Email: fdparsa@gmail.com

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests. No funding was received for this article.

References

- Stokes MAR, Johnson WD. Burns in the third world: an unmet need. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2017;30(4):243-246.

- American Burn Association. Burn Incidence Fact Sheet. Published 2024. Accessed June 4, 2025. https://ameriburn.org/resources/burn-incidence-fact-sheet/

- Hettiaratchy S, Dziewulski P. Pathophysiology and types of burns. BMJ. 2004;328:1427. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7453.1427

- Alharbi Z, Piatkowski A, Dembinski R, et al. Treatment of burns in the first 24 hours: simple and practical guide by answering 10 questions in a step-by-step form. World J Emerg Surg. 2012;7(1):13. doi:10.1186/1749-7922-7-13

- Rowan MP, Cancio LC, Elster EA, et al. Burn wound healing and treatment: review and advancements. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):243. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0961-2

- Kumar RJ, Kimble RM, Boots R, Pegg SP. Treatment of partial-thickness burns: a prospective, randomized trial using Transcyte. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(8):622-626. doi:10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03106.x

- Janzekovic Z. Early surgical treatment of the burned surface. Panminerva Med. 1972;14(7-8):228-232.

- Chiang RS, Borovikova AA, King K, et al. Current concepts related to hypertrophic scarring in burn injuries. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(3):466-477. doi:10.1111/wrr.12432

- Landry A, Geduld H, Koyfman A, Foran M. An overview of acute burn management in the emergency centre. African J of Emerg Med. 2013;3(1):22-29. doi:10.1016/j.afjem.2012.08.004

- Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, Winston B, Lindsay R. Burn wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(2):403-434. doi:10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006

- Goswami P, Sahu S, Singodia P, et al. Early excision and grafting in burns: an experience in a tertiary care industrial hospital of eastern India. Indian J of Plast Surg. 2019;52(3):337-342. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3402707

- Lee KC, Joory K, Moiemen NS. History of burns: the past, present and the future. Burns Trauma. 2014;2(4):169-180. doi:10.4103/2321-3868.143620

- Saaiq M, Zaib S, Ahmad S. Early excision and grafting versus delayed excision and grafting of deep thermal burns up to 40% total body surface area: a comparison of outcome. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2012;25(3):143-147.

- Ong YS, Samuel M, Song C. Meta-analysis of early excision of burns. Burns. 2006;32(2):145-150. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2005.09.005

- Pavoni V, Gianesello L, Paparella L, Buoninsegni LT, Barboni E. Outcome predictors and quality of life of severe burn patients admitted to intensive care unit. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:24. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-18-24

- Ayaz M, Bahadoran H, Arasteh P, Keshavarzi A. Early excision and grafting versus delayed skin grafting in burns covering less than 15% of total body surface area; a non- randomized clinical trial. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2014;2(4):141-145.

- Green HA, Bua D, Anderson RR, Nishioka NS. Burn depth estimation using indocyanine green fluorescence. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128(1):43-49. doi:10.1001/archderm.1992.01680110053005

- Flower RW, Hochheimer BF. A clinical technique and apparatus for simultaneous angiography of the separate retinal and choroidal circulations. Invest Ophthalmol. 1973;12(4):248-261.

- Leonard LG, Munster AM, Su CT. Adjunctive use of intravenous fluorescein in the tangential excision of burns of the hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66(1):30-33. doi:10.1097/00006534-198007000-00005

- Losken A, Styblo TM, Schaefer TG, Carlson GW. The use of fluorescein dye as a predictor of mastectomy skin flap viability following autologous tissue reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61(1):24-29. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e318156621d

- Raghuram AC, Stofman GM, Ziembicki JA, Egro FM. Surgical excision of burn wounds. Clin Plast Surg. 2024;51(2):233-240. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2023.11.002