Comparison of Surgical Complications in Staged Versus Combined Hysterectomy Approach in Masculinizing Bottom Surgery: A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Analysis

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background: Masculinizing (female-to-male) gender-affirming bottom surgeries (GABS) commonly include hysterectomies and can be performed in a staged manner or at the time of masculinizing genital surgery. Prior studies with small patient cohorts have suggested that adopting a combined approach increases the likelihood of complications. This study aimed to characterize patients undergoing gender-affirming masculinizing genital surgery with and without concurrent hysterectomies and determine whether there were additive risks of concurrent procedures.

Methods: The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database was used to identify patients with International Classification of Diseases-9/-10 gender dysphoria diagnoses who underwent masculinizing GABS (intersex for female to male, simple or complex scrotoplasty) from 2012 to 2022. Stratified by the presence of a concurrent hysterectomy, baseline characteristics, preoperative commodities, and 30-day postoperative outcomes were compared between single-stage GABS and those with concurrent hysterectomy.

Results: Of the 113 total patients included, 83 (73.5%) patients had a single-stage GABS and 30 (26.6%) patients had a GABS combined with hysterectomy. Baseline characteristics, including age, gender distribution, and preoperative comorbidities, were comparable between groups. The median operative time and hospital length of stay were similar between groups. However, single-stage GABS patients had higher rates of return to the operating room (14.5% vs 0.0%, P = .03), wound complications (22.9% vs 0.0%, P = .004), and all-cause complications (27.7% vs 6.7%, P = .02).

Conclusions: The results suggest that performing hysterectomies at the time of masculinizing GABS can be safe in appropriately selected patients. These findings highlight the potential safety benefits of combining GABS with hysterectomy and underscore the need for further research into optimizing outcomes for diverse patient populations, as a combined approach may improve efficiency, aid access to care, and improve patient satisfaction.

Introduction

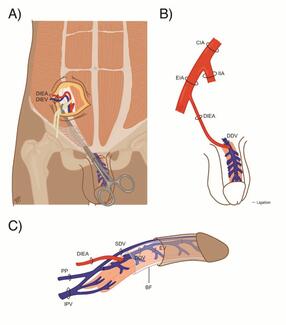

Gender-affirming procedures have significantly increased in prevalence in the past 5 years in the United States, with bottom surgeries being the second most common gender-affirming surgery (GAS).1 Depending on the goals of care, several options for gender-affirming bottom surgery (GABS) exist, including metoidioplasty and phalloplasty, both of which are considered masculinizing for patients assigned female at birth (AFAB).2 The goals of care in performing bottom GAS for transgender men (TGM) include relief of gender dysphoria, standing micturition, phallic sensation, and the ability to perform penetrative intercourse.3 The removal of natal reproductive organs, such as vaginectomies or hysterectomies, is often part of GABS. Common motives for removing the natal organs include affirming one’s gender, taking preventive health measures, and avoiding future gynecologic visits.4 For these reasons, hysterectomies are one of the most commonly performed genital gender affirmation surgeries in transmasculine and nonbinary patients who were AFAB. Masculinizing genital surgery can be done at the time of hysterectomy or later in a staged manner; each approach is associated with its own set of risks and benefits.1-3,5,6

Transgender individuals encounter many obstacles to receiving medical care. Performing a concurrent hysterectomy at the time of GABS may provide added benefits for these individuals7; however, there is considerable debate regarding the safety profiles associated with concurrent hysterectomy at the time of phalloplasty, as the limited number of small studies have had conflicting findings.4,5 There is limited published literature describing postoperative complication rates among individuals undergoing metoidioplasties with concurrent hysterectomies. The combined procedure may allow patients to reach their gender-affirming goals in fewer steps with less downtime, fewer missed wages, and better access to care for some patients. Therefore, it is imperative to assess whether this approach increases postoperative risk. Using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database, we examined differences in 30-day postoperative complications in patients undergoing GABS combined with hysterectomy compared with patients undergoing GABS alone.

Methods

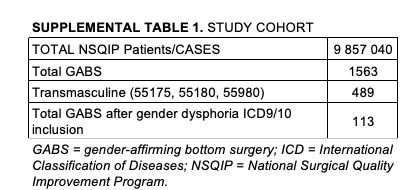

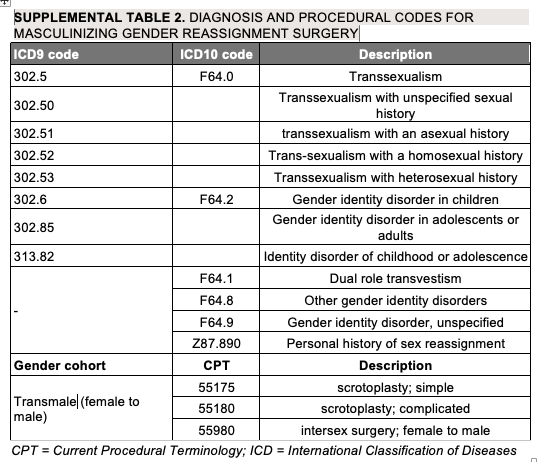

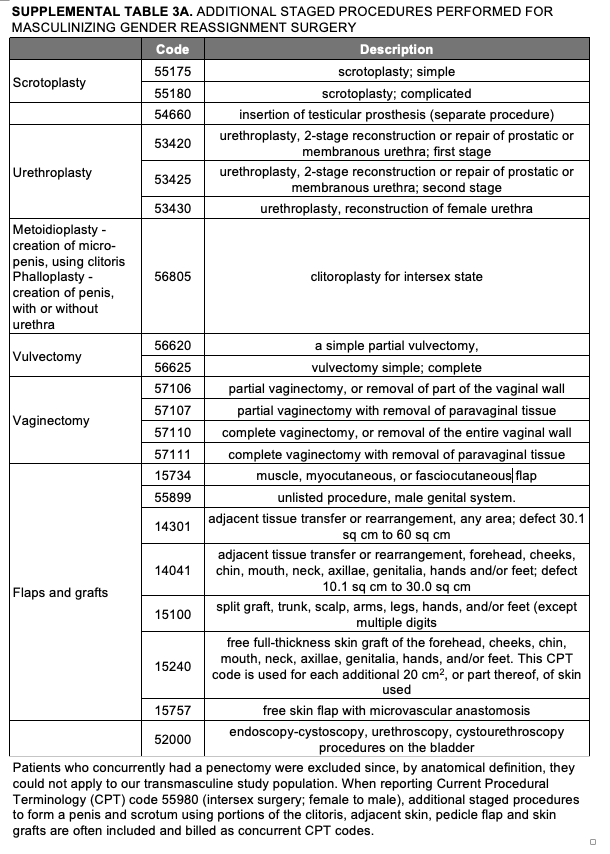

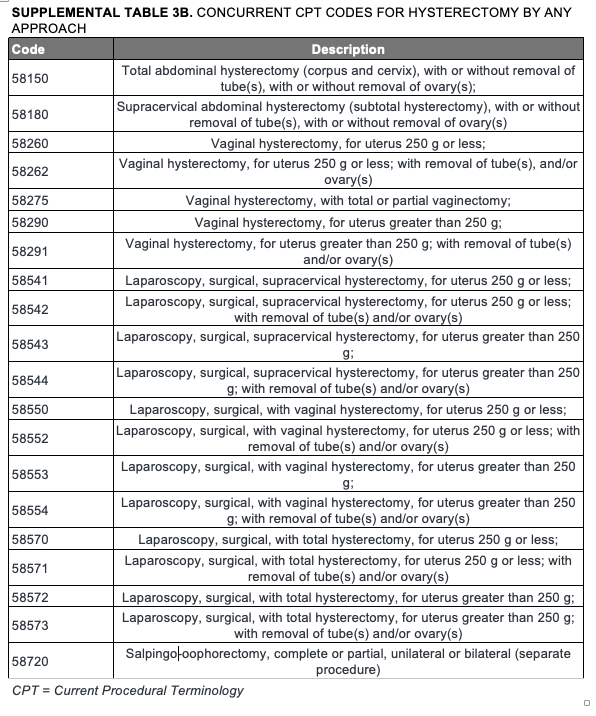

This study was determined to be exempt by our institutional review board. ACS-NSQIP is a database of surgical outcomes used to measure 30-day outcomes of surgical interventions with methods for data collection, sampling, and validation that are well established and have been previously described.8-11 We used the ACS-NSQIP database to identify patients with postoperative diagnosis codes (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-9 and ICD-10) of gender dysphoria who underwent masculinizing gender reassignment bottom surgery by any surgeon from 2012 to 2022. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and Medicare coverage criteria, eligible procedures for TGM (female-to-male) gender reassignment surgery include hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, vaginectomy, vulvectomy, metoidioplasty, phalloplasty, urethroplasty, scrotoplasty, and testicular prosthesis placement. Relevant Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for masculinizing bottom surgery—55980 (intersex surgery), 55175, and 55180 (simple and complicated scrotoplasty)—were included and used to identify qualifying cases (Supplemental Table 1). Patients undergoing concurrent hysterectomy, regardless of surgical approach (open or laparoscopic), were identified using the appropriate concurrent CPT code. When reporting CPT code 55980 (intersex surgery; female-to-male), additional staged procedures such as the formation of a penis and scrotum using portions of the clitoris, adjacent skin, pedicle flaps, and skin grafts are often included and billed concurrently. The full list of included and excluded procedures, along with the corresponding CPT and ICD-9/ICD-10 codes, is detailed in Supplemental Tables 2, 3A, and 3B.

Primary outcomes and statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics, preoperative comorbidities, perioperative outcomes (operative time), and postoperative outcomes (hospital length of stay, reoperation rates, and 30-day readmission rates) between patients undergoing masculinizing bottom surgery with hysterectomy and those undergoing the procedure without hysterectomy were compared. The primary outcomes of interest were the 30-day wound complication rate and the all-cause complication rate of the 2 groups. Wound complications included superficial surgical site infection, deep surgical site infection, organ-space surgical site infection, and wound disruptions. Mild systemic complications included incidences of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) requiring therapy, bleeding resulting in transfusion, pneumonia, sepsis, urinary tract infection, and renal insufficiency. Severe systemic complications included pulmonary embolism, unplanned intubation, ventilator support for greater than 48 hours, dialysis-requiring renal failure, stroke, cardiac arrest with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), myocardial infarction, septic shock, or death. All-cause complications included any adverse events within these categories.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp, Release 18); Student t tests were used for parametric variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for nonparametric data, and χ² tests for categorical variables. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Normally distributed continuous data were reported as means with SDs, while nonparametric continuous data was reported as medians with IQRs. Statistical significance was set at a P value of less than or equal to .05.

Results

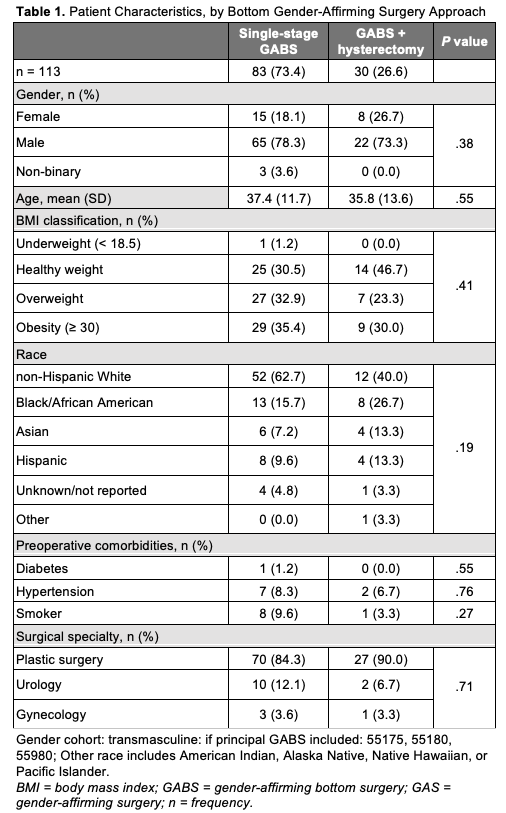

Demographic characteristics and preoperative comorbidities

A total of 113 patients who underwent GABS were included in this study; 83 (73.5%) patients had a single-stage GABS and 30 (26.6%) patients had a GABS combined with hysterectomy. The baseline characteristics and preoperative comorbidities of the 2 groups are summarized in Table 1. The average age of patients in the single-stage GABS group was 37.4 years (SD 11.7), compared with 35.8 years (SD 13.6) in the GABS-with-hysterectomy group (P = .55). Compared with 30% (9/30) of the GABS-with-hysterectomy cohort, 35.4% (29/83) of the single-stage GABS patients were classified as obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) (P = .41). Preoperative comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, and smoking status, were not significantly different between the groups. Smoking prevalence was 9.6% (8/83) in the single-stage group and 3.3% (1/30) in the combined group (P = .27). Diabetes was present in 1 (1.2%) patient in the single-stage group and absent in the GABS-with-hysterectomy group (P = .55). In both groups, most GABS were performed by plastic surgeons: 84.3% (70/83) of single-stage GABS cases and 90% (27/30) of GABS-with-hysterectomy cases. Urologists performed 12.1% (10/83) of the single-stage procedures and 6.7% (2/30) of the combined procedures, while gynecologists accounted for 3.6% (3/83) and 3.3% (1/30) of cases in the single-stage and combined groups, respectively (P = .71).

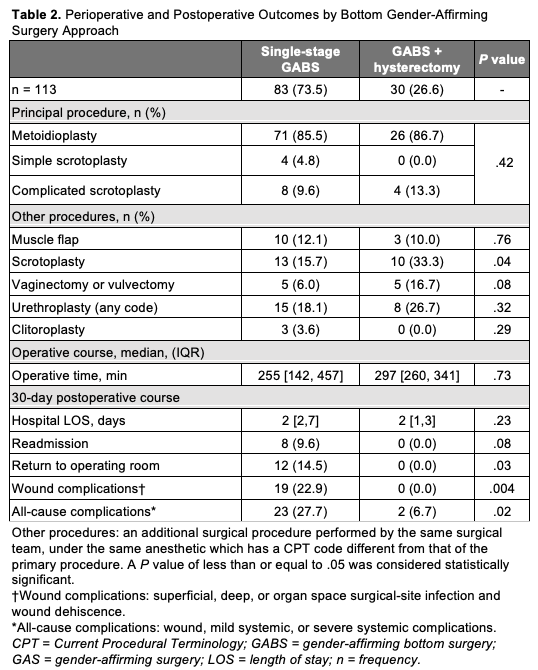

Operative and 30-day complication course

Table 2 summarizes the perioperative and postoperative outcomes for patients undergoing single-stage masculinizing GABS and GABS combined with hysterectomy. Intersex; female-to-male was the most common principal procedure for both groups (P = .42). There were significant differences in the proportion of patients who had concurrent scrotoplasty, with 33.3% of patients in the GABS-with-hysterectomy group undergoing scrotoplasty compared with 15.7% in the single-stage group (P = .04). The proportion of patients who had concurrent vaginectomy/vulvectomy (P = .08), urethroplasty (P = .32), and clitoroplasty (P = .29), was not significantly different between groups. The median operative time was longer for the GABS-with-hysterectomy group (297 minutes) than for the single-stage GABS group (255 minutes); however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .73). The median length of hospital stay was 2 days for both groups; this difference was also not statistically significant. However, the rate of return to the operating room was significantly higher in the single-stage GABS group than in the GABS-with-hysterectomy group (14.5% vs 0.0%, P = .03). While readmission rates were higher in the single-stage GABS group (9.6%) compared with the combined group (0.0%), this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .08). Wound complications occurred only in the single-stage group (22.9%) (P = .004). All-cause complications were significantly more common in the single-stage GABS group compared with the combined group (27.7% vs 6.7%, P = .02).

Discussion

GABS for patients who were AFAB, such as metoidioplasty or phalloplasty, can be performed in single or multiple stages. Hysterectomies are commonly performed for the treatment of gender dysphoria and subsequent preparation for gender affirmation surgery.12,13 In order to promote operative efficiency and reduce the burden of recovery for patients, some centers have advocated for performing hysterectomies at the time of GABS in appropriately selected patients. Prior studies have shown that the incidence of complication rates following hysterectomies in the GABS patient population is similar to the complication rates found in cisgender women.12 Our study is the largest to date examining complication rates between asynchronous GABS and concurrent hysterectomy. In our ACS-NSQIP cohort of 113 patients, we found no increased risks in the incidence of wound or all-cause complications between patients undergoing masculinizing bottom surgery combined with hysterectomy compared with patients undergoing masculinizing bottom surgery alone. Our findings suggest that offering a hysterectomy at the time of GABS may be a safe option for appropriately selected patients.

While we did not observe significant differences in clinical and demographic characteristics among patients undergoing concurrent hysterectomies compared with those undergoing hysterectomies alone, there were some important findings that warrant discussion. Notably, there were generally lower rates of all examined preoperative comorbidities in the concurrent hysterectomy group, although not statistically significant. These findings suggest that providers may select patients with low-risk profiles when offering concurrent procedures. Additionally, a greater proportion of non-White patients underwent concurrent procedures—nearly double the number of Asian patients and African-American patients compared with White patients. The differences in the racial-ethnic distribution of concurrent procedures warrant consideration of the potential socioeconomic implications underlying the utilization of concurrent procedures. Existing literature has consistently demonstrated health care disparities, including the accessibility of gender-affirming care among non-White patient populations.14,15 Savings in recovery time when using concurrent procedures may be particularly resonant for patients from diverse backgrounds with limited resources who may be encountering additional barriers to gender-affirming care. Plastic surgeons were more frequently the primary surgeons for the principal procedures in those who underwent concurrent surgical procedures. Hysterectomies, often considered secondary procedures, are typically performed by gynecologists, and the predominance of plastic surgeons in performing these interventions highlights the inherently multidisciplinary approach in the delivery of gender-affirming care and surgeries. Close collaboration among plastic surgeons, gynecologists, and urologists may ensure comprehensive patient care.

Studies have shown that a significant proportion of patients who initially seek hysterectomies as a GAS will ultimately pursue GABS.16,17 Additionally, as cervical cancer screening becomes a challenging task post-vaginectomy, hysterectomy prior to vaginectomy is necessary.4,18 While the concurrent approach may streamline surgical interventions and reduce the overall number of procedures, the potential complications associated with urethroplasties, particularly in patients who were AFAB, warrant discussion. Though concurrent vaginectomy and urethral lengthening procedures during GABS are generally considered safe, specific complications, such as neo-urethral fistulas and strictures, may arise.2,3,5 Other common adverse outcomes include issues with voiding, such as dribbling, urethral diverticula, and vaginal remnants.1,2,6 These complications are often associated with longer operative times4; however, the literature on the incidence of lower urinary tract symptoms is limited because of inadequate postoperative follow-up after metoidioplasty. One study analyzing outcomes after concurrent vaginectomy found that a high percentage of TGM with neo-urethral strictures were presenting with vaginal cavity remnants post-surgery.5 Some surgeons advocate for the vaginectomy to be done in a particular stage of the phalloplasty so the vaginal mucosa can serve as grafts for the reconstruction.19 In a retrospective single-center study comparing complication rates in 66 transmasculine patients who underwent a Stage 1 phalloplasty (consisting of a vaginectomy, urethral lengthening, and possible scrotoplasty) with asynchronous or concurrent hysterectomies, results showed that patients undergoing asynchronous hysterectomies have more neo-urethral complications than the concurrent group. Nonetheless, the 2 groups had comparable rates in the incidence of superficial surgical infections and other postoperative complications.4 Although these procedure-specific complications are not reported in the ACS-NSQIP and may present beyond a 30-day postoperative period, the length of hospital stay and the proportion of patients remaining in the hospital for more than 30 days can still provide useful information for both plastic surgeons and urologists participating in the surgical care of these patients.

Though anecdotal in practice, some providers remain conservative in their surgical approach to offering GABS, fearing a greater recovery burden due to the number of concurrent procedures. Given the considerable uncertainty regarding the risk associated with concurrent hysterectomy at the time of masculinizing bottom surgery, some surgeons selectively offer a 2-stage approach to patients. In turn, patients who strongly desire both a hysterectomy as well as another masculinizing bottom surgery may still only be offered a 2-stage approach given concerns for increased risk of surgical complications following combined procedures.20-22 Although the median total operative time was the same in our study cohort, reoperation rates, wound complications, and all-cause complications were higher in the asynchronous group. We surmise that this is due to the relatively lower risk of patients undergoing the concurrent procedures. Despite all the mixed results of prior studies, our data strongly suggest that offering hysterectomies at the time of GABS is a safe option for many patients. The combined procedure may allow patients to reach their gender-affirming end goals in fewer steps, offer less downtime and missed wages, and allow better access to care for some patients.

Understanding the safety of gender-affirming hysterectomies when performed concurrently with other genital GAS remains vital; there are no standardized or agreed-upon approaches for the safety profile of asynchronous vs concurrent GABS or regarding which patients would benefit from a staged vs a combined procedure. Patients in search of gender-affirming care have unique health care needs and frequently encounter obstacles.7 Only half of state Medicaid programs cover GAS.23 Although federal and state-level policy changes were designed to improve access to gender-affirming care, some policies remain restrictive.24-26 Stringent preoperative requirements for insurance coverage policies perpetuate disparities, as they often require multiple clinician-provided referral letters, with some patients even traveling out of state for GABS.27-30 Additional barriers, specifically in multiple-stage GABS, may include frequent leaves of absence from work due to multiple recovery periods. Offering concurrent GABS may circumvent accessibility issues by allowing those with limited access to care to undergo all necessary GABS procedures simultaneously, therefore improving accessibility and potentially optimizing patient satisfaction.31 Concurrent procedures have the potential to reduce the need to miss work, especially in patients without the financial means and social support for multiple recovery periods.32 Furthermore, combined procedures can be mutually beneficial on a health system and patient level, because limiting multiple procedures to 1 general anesthesia operation and reducing hospital stays offers both cost-effective benefits to the hospital and patient. Based on our study results, appropriately selected patients without significant comorbidities can be safely offered joint hysterectomies at the time of GABS. These findings can better guide surgeons’ preoperative counseling, allowing them to consider a patient’s care goals as well as potential social and health care barriers as they engage in shared decision-making with patients.33

Limitations

The present study utilized a national surgical database to evaluate the safety profile of concurrent hysterectomy and masculinizing GABS, representing the largest patient sample for this topic to the authors’ knowledge. However, the small sample size of the concurrent hysterectomy group (n = 30) and of the study cohort overall reduces the statistical power, subsequently limiting the generalizability of our findings, particularly to populations served outside of NSQIP-participating institutions.34 Although the NSQIP exists to standardize and optimize national reporting of surgical outcomes, institutional variations in medical records and procedural billing may affect data accuracy.35,36 Additionally, the infrequent use of gender dysphoria ICD-9/-10 codes prior to 2015 may underestimate the true patient population. Though the NSQIP database is comprehensive in capturing a robust set of postoperative complications, delayed procedure-specific complications of GABS known to occur well beyond the 30-day postoperative period could not be evaluated.1,6 Although the current findings suggest potential benefits associated with concurrent procedures, caution is advised in generalizing the findings to diverse patient populations. The study was unable to account for factors such as insurance status, income, or social support. Further research is needed to explore outcomes across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, as well as to evaluate patient selection criteria and economic implications.

Conclusions

GAS will continue to be sought by patients seeking symptomatic treatment of gender dysphoria. Complication rates will vary depending on the patients’ preoperative characteristics and the GAS performed, as well as variations in surgical technique. Our results suggest that hysterectomies can be performed safely and in combination with masculinizing GABS in healthy individuals with gender dysphoria. Our study’s findings can inform preoperative patient counseling and guide surgeon risk assessment while optimizing access to care and improving patient satisfaction in this population. These findings can also guide preoperative counseling for patients considering a concurrent hysterectomy with GABS.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Oluwaseun D. Adebagbo, MD1,2; Micaela J. Tobin, BA1;

Affiliations: 1Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; 2Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Fenway Health, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; 4Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Correspondence: Ryan P. Cauley, MD, MPH, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, LMOB 5A, Boston, MA 02215, USA. Email: rcauley@bidmc.harvard.edu

Ethics: IRB Protocol #2024D000147; the work described in this manuscript involves the use of human subjects and has been conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for experiments involving humans, as well as the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) Recommendations.

Funding: Tufts University School of Medicine; The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Award Number T32TR004417. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosures: The abstract was presented at the New England Section of the American Urological Association in Providence, Rhode Island on September 11, 2024 and at Plastic Surgery The Meeting in San Diego, California on September 27, 2024.

References

- Scott KB, Thuman J, Jain A, Gregoski M, Herrera F. Gender-affirming surgeries: a national surgical quality improvement project database analyzing demographics, trends, and outcomes. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;88(5 Suppl 5):S501-S507. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000003157

- Waterschoot M, Hoebeke P, Verla W, et al. Urethral complications after metoidioplasty for genital gender affirming surgery. J Sex Med. 2021;18(7):1271-1279. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.023

- Medina CA, Fein LA, Salgado CJ. Total vaginectomy and urethral lengthening at time of neourethral prelamination in transgender men. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(10):1463-1468. doi:10.1007/s00192-017-3517-y

- Ha B, Morrill MY, Salim AM, Stram D, Weiss E. Differences in surgical complications for stage 1 phalloplasty with concurrent versus asynchronous hysterectomy in transmasculine patients. Perm J. 2022;26(4):49-55. doi:10.7812/TPP/22.054

- Schardein JN, Li G, Zaccarini DJ, Caza T, Nikolavsky D. Histological evaluation of vaginal cavity remnants excised during neourethral stricture repair in transgender men. Urology. 2021;156:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.06.044

- Ferrando CA. Adverse events associated with gender affirming vaginoplasty surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(2):267.e1-267.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.033

- Paidisetty P, Sathyanarayanan S, Kuan-Pei Wang L, et al. Assessing the readability of online patient education resources related to neophallus reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2023;291:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2023.06.012

- Cohen ME, Ko CY, Bilimoria KY, et al. Optimizing ACS NSQIP modeling for evaluation of surgical quality and risk: patient risk adjustment, procedure mix adjustment, shrinkage adjustment, and surgical focus. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(2):336-346.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.027

- Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs' NSQIP: the first national, validated, outcome-based, risk-adjusted, and peer-controlled program for the measurement and enhancement of the quality of surgical care. National VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg. 1998;228(4):491-507. doi:10.1097/00000658199810000-00006

- McNelis J, Castaldi M. "The National Surgery Quality Improvement Project" (NSQIP): a new tool to increase patient safety and cost efficiency in a surgical intensive care unit. Patient Saf Surg. 2014;8:19. doi:10.1186/1754-9493-8-19

- Fink AS, Campbell DA Jr, Mentzer RM Jr, et al. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in non-veterans administration hospitals: initial demonstration of feasibility. Ann Surg. 2002;236(3):344-353; discussion 353-354. doi:10.1097/00000658-200209000-00011

- Bretschneider CE, Sheyn D, Pollard R, Ferrando CA. Complication rates and outcomes after hysterectomy in transgender men. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):1265-1273. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002936

- Ergeneli MH, Duran EH, Ozcan G, Erdogan M. Vaginectomy and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy as adjunctive surgery for female-to-male transsexual reassignment: preliminary report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;87(1):35-37. doi:10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00091-3

- Trilles J, Chaya BF, Brydges H, et al. Recognizing racial disparities in postoperative outcomes of gender affirming surgery. LGBT Health. 2022;9(5):333-339. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2021.0396

- Jolly D, Boskey ER, Ganor O. Racial disparities in the 30-day outcomes of gender-affirming chest surgeries. Ann Surg. 2023;278(1):e196-e202. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000005512

- Carbonnel M, Karpel L, Cordier B, Pirtea P, Ayoubi JM. The uterus in transgender men. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(4):931-935. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.07.005

- Vallée A, Feki A, Ayoubi JM. Endometriosis in transgender men: recognizing the missing pieces. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1266131. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1266131

- Dutton L, Koenig K, Fennie K. Gynecologic care of the female-to-male transgender man. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(4):331-337. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.02.003

- Jun MS, Shakir NA, Blasdel G, et al. Robotic-assisted vaginectomy during staged gender-affirming penile reconstruction surgery: technique and outcomes. Urology. 2021;152:74-78. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.01.024

- Bizic M, Stojanovic B, Bencic M, Bordás N, Djordjevic M. Overview on metoidioplasty: variants of the technique. Int J Impot Res. 2020;33(7):762-770. doi:10.1038/s41443-020-00346-y

- Djordjevic ML, Stanojevic D, Bizic M, et al. Metoidioplasty as a single stage sex reassignment surgery in female transsexuals: Belgrade experience. J Sex Med. 2009;6(5):1306-1313. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01065.x

- Stojanovic B, Bencic M, Bizic M, Djordjevic ML. Metoidioplasty in gender affirmation: a review. Indian J Plast Surg. 2022;55(2):156-161. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1740081

- Zaliznyak M, Jung EE, Bresee C, Garcia MM. Which U.S. states' Medicaid programs provide coverage for gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming genital surgery for transgender patients?: a state-by-state review, and a study detailing the patient experience to confirm coverage of services. J Sex Med. 2021;18(2):410-422. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.11.016

- Patel H, Camacho JM, Salehi N, Garakani R, Friedman L, Reid CM. Journeying through the hurdles of gender-affirming care insurance: a literature analysis. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e36849. doi:10.7759/cureus.36849

- Padula WV, Baker K. Coverage for gender-affirming care: making health insurance work for transgender Americans. LGBT Health. 2017;4(4):244-247. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0099

- Goldenberg T, Reisner SL, Harper GW, Gamarel KE, Stephenson R. State-level transgender-specific policies, race/ethnicity, and use of medical gender affirmation services among transgender and other gender-diverse people in the United States. Milbank Q. 2020;98(3):802-846. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12467

- Wilson EC, Chen YH, Arayasirikul S, Wenzel C, Raymond HF. Connecting the dots: examining transgender women's utilization of transition-related medical care and associations with mental health, substance use, and HIV. J Urban Health. 2015;92(1):182-192. doi:10.1007/s11524-014-9921-4

- Almazan AN, Boskey ER, Labow B, Ganor O. Insurance policy trends for breast surgery in cisgender women, cisgender men, and transgender men. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(2):334e-336e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000005852

- Hauc SC, Long AS, Mozaffari MA, et al. Association of health policy with payment and regional shifts in gender-affirming surgery. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(7):630-631. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.1053

- Downing J, Holt SK, Cunetta M, Gore JL, Dy GW. Spending and out-of-pocket costs for genital gender-affirming surgery in the US. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(9):799-806. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.2606

- Reilly ZP, Fruhauf TF, Martin SJ. Barriers to evidence-based transgender care: knowledge gaps in gender-affirming hysterectomy and oophorectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):714-717. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003472

- Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23(Suppl 1):S1-S259. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

- Robinson IS, Blasdel G, Cohen O, Zhao LC, Bluebond-Langner R. Surgical outcomes following gender affirming penile reconstruction: patient-reported outcomes from a multi-center, international survey of 129 transmasculine patients. J Sex Med. 2021;18(4):800-811. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.01.183

- Knoedler S, Knoedler L, Wu M, et al. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative complications after rhinoplasty: a multi-institutional ACS-NSQIP analysis. J Craniofac Surg. 2023;34(6):1722-1726. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000009553

- Molina CS, Thakore RV, Blumer A, Obremskey WT, Sethi MK. Use of the national surgical quality improvement program in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1574-1581. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3597-7

- Hammermeister K. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: learning from the past and moving to the future. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5 Suppl):S69-S73. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.007