Single-Stage Breast Reconstruction With Immediate Free Nipple Grafting in Goldilocks Mastectomy Using Composite Nipple Graft and “Donut” Areolar Full-Thickness Skin Graft Shared From Noncancerous Breast

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Questions

- What are the differences between the application of the Goldilocks technique in this patient and other prevalent non-implant post-mastectomy breast reconstruction methods?

- How can free nipple grafting (FNG) be used in conjunction with the Goldilocks method of breast reconstruction?

- Is there risk of cancer recurrence after mastectomy, and what is the risk of cancer occurrence in the nipple-areolar complex after sharing from the noncancerous breast?

- What are the benefits of a single-stage mastectomy and reconstruction, and why would immediate FNG be employed during Goldilocks for single-stage breast reconstruction?

Case Description

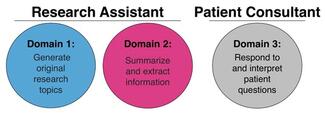

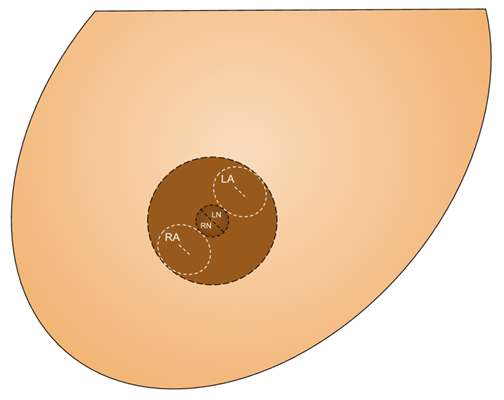

A 68-year-old woman with a medical history of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, appendectomy, 2 C-sections, and a hysterectomy presented after mammogram and ultrasonography screening with a subcentimeter mass at the 6 o'clock position 13 cm from the nipple of the left breast. Diagnosis was confirmed by core needle biopsy, which demonstrated a triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma grade 3. Genetic testing found the patient to be positive for a BRCA1 mutation. The breasts were pendulous and grade 3 ptotic. The patient reported wearing a K-cup bra size, with the left breast being much larger than the right (Figure 1). Based on the patient’s wishes to have reconstruction without the use of implants and to have the nipple-areolar complexes (NACs) lifted, bilateral Goldilocks mastectomy with immediate bilateral NAC reconstruction was performed in a single procedure.

Figure 1. Preoperative markings in a patient with left-sided breast cancer. The patient had grade 3 ptosis and was not a candidate for nipple-sparing mastectomy. The right nipple areolar complex (NAC) was marked for use in the creation of bilateral NACs. The markings denote the distances of the anatomical structures in relation to the new nipples (7 = new nipple to inframammary fold, 14 = new nipple to sternum, 22/23 = new nipple to clavicle with left clavicle slightly higher, 25 = suprasternal notch to new nipple).

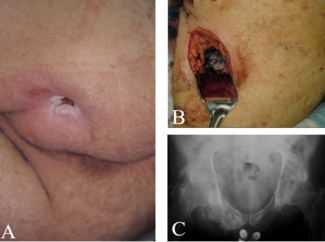

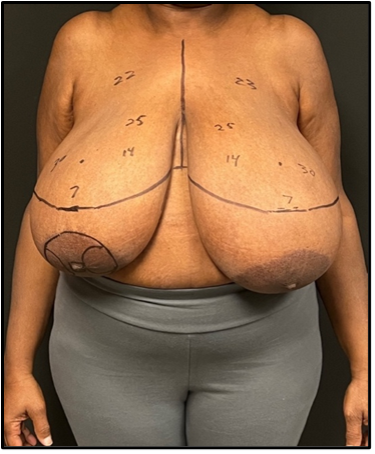

A full-thickness “donut” areolar skin graft and composite nipple graft were harvested from the noncancerous right breast. “Donut” describes the circular shape of the areolar full-thickness skin grafts used to reconstruct both the cancerous and noncancerous side. The composite nipple graft was taken from the noncancerous side, divided into halves, and fashioned into 2 separate composite nipple grafts (Figures 2, 3). Follow-up showed excellent shape and symmetry of the breasts, and the NACs were adherent and healing well (Figure 4). In 1 stage, the Goldilocks procedure achieved mound reconstruction, reduction, and lift with conclusive nipple restoration using the patient’s noncancerous tissue with no delay in adjuvant therapy, including radiation (Figure 5).

Figure 2. Schematic diagram showing markings used in the “donut” areolar skin graft and composite nipple graft technique. The incisions for the “donut” areolar graft are depicted in white, labeled RA (right areola) and LA (left areola). Outlined in black are the incisions used to harvest the composite nipple graft, in which the nipple is halved, thereby producing the RN (right nipple) and LN (left nipple). To construct the new nipple-areolar complexes, the RN and LN will be placed inside the central “donut hole” of the RA and LA, respectively.

Figure 3. Postoperative patient image after Goldilocks mastectomy with immediate free nipple grafting using a composite nipple graft and a “donut” areolar full-thickness skin graft shared from the noncancerous breast. The left breast was larger, and no implants were used postoperatively in anticipation of radiation.

Figure 4. Postoperative image 4 weeks after radiation of the left breast, with fair symmetry.

Figure 5. The final result 10 months after the initial procedure with well-healed and adherent reconstructed nipple-areolar complexes, with good symmetry despite radiation of the left breast.

Q1. What are the differences between the application of the Goldilocks technique in this patient and other prevalent non-implant post-mastectomy breast reconstruction methods?

Among the various surgical techniques used for breast reconstruction after mastectomy, the Goldilocks technique has emerged as a notable approach for select patients since its inception in 2012.1 This technique makes use of the patient’s own residual cutaneous tissue flaps from a skin-sparing mastectomy to create a fully autologous breast mound. Patients indicated for this method typically have excess skin and subcutaneous tissue that allows for effective use of the redundant tissue available after mastectomy. Such patients will present with macromastia or moderate to severe ptosis.1-4 The patient discussed in this report was obese and wished to avoid the use of implants for reconstruction while optimizing breast projection and fullness.

The Goldilocks mastectomy offers a suitable middle ground between implantation and classic non–implant-based methods of breast reconstruction in patients who contraindicate for such procedures.1 Traditional options for autologous post-mastectomy breast reconstruction are myocutaneous flaps, skin/fat flaps, or hybrid flap techniques that involve fat grafts.5 Perforator flaps like the deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) or alternative non–abdominal-based flaps like the profunda artery perforator and lateral thigh perforator flaps are generally considered superior to myocutaneous flaps such as the transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) because they do not compromise the musculature yet maintain the same benefits of a myocutaneous flap.5,6 Generally, autogenous flaps are reserved until after radiation is completed. While these reconstruction methods offer a considerable ability to sculpt and project the breast with favorable cosmetic results, deficits in the use of flaps for reconstruction are the increased length of time and complexity of the procedures, which is in contrast to the faster and relatively simpler Goldilocks procedure.7 Autologous flaps harvested from distant body sites also present the potential for flap and donor-site complications, uniquely hernia or abdominal bulge in the case of TRAM flaps.7,8 This is in contrast to the postoperative complications associated with the Goldilocks procedure, which are notably fewer and localized only to the breast region under reconstruction. In fact, Chaudhry et al reported an overall complication rate of less than 10% for the Goldilocks procedure.9 Importantly, obese patients are at an increased risk of the complications associated with prosthetic and distant autologous flaps and are, therefore, often contraindicated for these breast reconstruction methods.1,8,10 Thus, the Goldilocks technique can provide a safe option for patients of this demographic by avoiding the risk of these complications while simultaneously offering the advantages of shorter operative and recovery times.7

A disadvantage of the Goldilocks method is that the post-reconstruction breast size is limited by the pre-mastectomy breast size.7 In addition, the mastectomy skin flap thickness plays a part in the final breast volume and can be highly variable.7 For patients seeking to improve post-reconstruction asymmetry, address contour issues, or adjust volume, adjunctive autologous fat grafts can be harvested from areas of high adiposity and used to lipofill the breast.5 However, this compromises the benefits of the single surgical operation that the Goldilocks mastectomy offers. Depending on the techniques of the surgeon, lateral redundant breast tissue is another possible disadvantage of the Goldilocks mastectomy; this could also require a secondary stage to address, thereby nullifying the original single-stage advantage of the technique.9 Historically, the NAC was removed during a Goldilocks reconstruction because of the nature of the procedure, which involved the lower areolar border being tucked under the skin envelope of the upper pole—an obvious disadvantage due to the suboptimal aesthetics and loss of sensation.1 Recent innovations have been made to maintain the NAC and thus improve the technique11; however, these methods make use of a dermal pedicle to maintain blood supply to the NAC, which is less reliable, and do not describe composite nipple grafting with a “donut” areolar full-thickness skin graft, as we do here.

Q2. How can free nipple grafting (FNG) be used in conjunction with the Goldilocks method of breast reconstruction?

In the original description of the Goldilocks mastectomy by Richardson and Ma, the procedure did not salvage the NAC.1 Thus, further procedures were developed to allow for the preservation of the NAC, increasing patient satisfaction and improving psychological well-being.12-14 One such adaptation is the nipple-sparing Goldilocks mastectomy, which uses a dermal pedicle to preserve the nipple.15 One study concluded that the procedure was an appealing choice for patients with large or ptotic breasts. However, there were some complications, including ischemia of the NAC and subsequent loss of the nipple, total and partial flap loss, seroma development, and superficial NAC necrosis.15

The high risk of NAC ischemia and resulting nipple necrosis is the primary reason why nipple-sparing mastectomies are seldom offered to patients with large or ptotic breasts.12,14 An alternative method of NAC preservation that may be beneficial to these patients is free nipple grafting (FNG). Free nipple grafts are full-thickness skin grafts in which the nipple is harvested and relocated onto deepithelialized tissue in the most desirable location on the new breast mound.12,16 FNG also provides an option for constructing 2 separate nipple grafts from a single, split nipple—a valuable technique for patients who possess only 1 NAC.12,13

FNG has reportedly lead to high patient satisfaction and aesthetically pleasing outcomes in these patients.12 Superficial necrosis of the nipple is possible with FNG, though it is temporary and resolves as the necrotic eschar is shed.16 Additional complications of FNG include loss of sensation to the nipple and inability to breastfeed, as well as NAC hypopigmentation, which can be remedied by using a thicker graft.16 Lastly, some amount of nipple protrusion may be lost with FNG.15

In patients with extensive breast cancer, FNG may not be possible from both sides. However, the nature of FNG lends itself to extensive tissue sampling of the NAC. If cancer is undetectable via an intraoperative subareolar frozen section, grafting may continue.17 Bilateral FNGs from the bilateral NAC has been reported with the Goldilocks techinque.10 Our FNG reconstruction with the Goldilocks method was performed from 1 NAC on the noncancerous side and was therefore smaller. Composite grafts have a better chance of revascularizing if small. Procedures that offer NAC preservation may be an appropriate treatment option when it is oncologically safe and when a favorable postoperative NAC position can be achieved following mastectomy. Thus, there should be no dimpling or distortion of the NAC prior to grafting, as these features may suggest oncologic risk. The ideal NAC position should be at or above the inframammary fold to be a candidate for nipple-sparing mastectomy. Aside from cases where cancer may involve the NAC or when the NAC location is suboptimal, FNG provides a safe alternative that allows for excellent placement.

Q3. Is there risk of cancer recurrence after mastectomy, and what is the risk of cancer occurrence in the NAC after sharing from the noncancerous breast?

When evaluating options for breast reconstruction following a mastectomy, it is essential to consider the residual breast tissue, the viability of autologous tissue, and the patient’s genetic predisposition to future breast cancers. Surgical techniques significantly influence the quantity of tissue remaining, with studies on skin-sparing mastectomy indicating that 5% to 60% of cases retain residual breast tissue, particularly in flaps thicker than 5 mm.18 Surgeons must carefully evaluate whether the tissue they intend to leave behind is viable for future reconstruction, as clearing margins is of utmost priority. Some cases from the studies referenced previously left behind residual disease, thus compromising the initial purpose of the procedure. In a similar 2014 study, 76.2% of specimen margins from 206 breasts following mastectomy were found to be positive for breast tissue. The majority of the residual tissue was found in the lower outer quadrant and the middle circle of the superficial dissection plane, thus indicating that these are high-risk regions that may require special care to ensure adequate margins.19 Even when residual tissue appears benign, a more comprehensive removal of all breast tissue may offer a more reliable approach to minimizing the risk of cancer recurrence.

The use of autologous tissue in breast reconstruction has been a well-established method following total mastectomy. However, given the significant risk of cancer recurrence in breast tissue despite aggressive surgical measures, the potential for reconstruction using benign tissue from the contralateral breast warrants consideration. Unfortunately, data on the risk of recurrence associated with this approach remains limited. A review of the literature did identify a notable case in which a breast cancer patient developed invasive ductal carcinoma in the shared/unaffected nipple following DIEP flap reconstruction and NAC reconstruction using tissue from the contralateral, noncancerous breast. Approximately 7.5 years postoperative, scrape cytology revealed a new primary malignancy in the transplanted nipple tissue.20 Only 1 other report was found, which cited Paget disease arising 6 years after nipple reconstruction with tissue obtained from the contralateral/unaffected side.21 To our knowledge, these cases represent the only known cases of cancer arising in the nipple after transplantation from noncancerous grafted NAC tissue. Therefore, this risk is minuscule, and NAC sharing is considered safe.

In conclusion, when pursuing breast reconstruction post-mastectomy, emphasis should be placed on clearing all cancerous margins and considering the potential risks associated with residual tissue. In regard to NAC reconstruction, the use of nipple grafts harvested from the contralateral noncancerous NAC tissue is considered a safe method of reconstruction, as the advent of cancer in NAC tissue has been shown in literature to be exceedingly rare. Even given its profoundly low rate of occurrence, clinicians should still recognize the potential for de novo cancers to develop in grafted nipple tissue.

Q4. What are the benefits of a single-stage mastectomy and reconstruction, and why would immediate free nipple grafting be employed during Goldilocks for single-stage breast reconstruction?

The decision to implement an FNG in conjunction with the Goldilocks mastectomy to constitute a single-stage mastectomy and reconstructive procedure is rooted in several clinical and patient-conscious considerations. These considerations are the same as those for a single-stage mastectomy and breast reconstruction. In this case cancer, severe ptosis, and a history of preexisting comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia further supported the decision for single-stage mastectomy and immediate free nipple grafing.22 By combining the mastectomy, breast reconstruction, and FNG procedures, a single operation reduces the number of surgeries needed and decreases the overall time the patient spends under anesthesia. This can also lead to a shorter recovery time, as the patient only needs to recover from a single surgery.23

Schwartz et al have described a single-stage Goldilocks and free nipple graft for 1 breast combined with only areola grafting for the other breast.23 Using our shared double “donut” areolar full-thickness skin grafts and halved composite nipple grafts, we provide a symmetric and true 1-stage reconstruction of both mounds and NACs with bilateral nipples. During these immediate reconstructive procedures, the oncological surgeon and plastic surgeon can coordinate to ensure the optimal use of tissues to achieve a better aesthetic result than if the procedures were conducted separately.

Undergoing mastectomy and reconstruction with simultaneous placement of the FNG can have psychological and emotional benefits. Having a breast contour and nipple graft in place after surgery can mitigate the negative body image and self-esteem impacts of a mastectomy and nipple loss. This can also alleviate anxiety associated with awaiting a second surgery in the future. Likewise, combining procedures may reduce the overall medical costs associated with multiple hospital stays, surgeries, and recovery periods, thereby reducing the stress associated with money and scheduling. While not all patients are candidates for single-stage procedures because of longer and more complex surgery, health conditions, or personal preference, an immediate single-stage operation is often preferred because of the combined benefits of improved psychological well-being, better aesthetic results, and a more streamlined surgical and recovery process.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Colton H. Connor, BS1; Shriya Dodwani, BA1; Quinton L. Carr, BA1; Claire Fell, BS1; Sierra Shockley, MS1; Ryan Cantrell, BS1; Wilson Huett, MD2; Bradon J. Wilhelmi, MD2

Affiliations: University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky; 2Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky

Correspondence: Bradon J. Wilhelmi, MD, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville, 550 South Jackson Street, ACB 2nd Floor, Louisville, KY 40202, USA. Email: bradon.wilhelmi@louisville.edu

Ethics: The patients in this document have been provided informed consent on the use of their images and granted the use of their images for scientific publications.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

References

1. Richardson H, Ma G. The Goldilocks mastectomy. Int J Surg. 2012;10(9):522-526. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.08.003

2. Zavala KJ, Kwon JG, Han HH, Kim EK, Eom JS. The Goldilocks technique: an alternative method to construct a breast mound after prosthetic breast reconstruction failure. Arch Plast Surg. 2019;46(5):475-479. doi:10.5999/aps.2018.00808

3. Ogawa T. Goldilocks mastectomy for obese Japanese females with breast ptosis. Asian J Surg. 2015;38(4):232-235. doi:10.1016/j.asjsur.2013.07.003

4. Krishnan NM, Bamba R, Willey SC, Nahabedian MY. Explantation following nipple-sparing mastectomy: the Goldilocks approach to traditional breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(4):795e-796e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000001130

5. Garza R III, Ochoa O, Chrysopoulo M. Post-mastectomy breast reconstruction with autologous tissue: current methods and techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(2):e3433. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000003433

6. Blondeel PN. One hundred free DIEP flap breast reconstructions: a personal experience. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52(2):104-111. doi:10.1054/bjps.1998.3033

7. Ghanouni A, Thompson P, Losken A. Outcomes of the Goldilocks technique in high-risk breast reconstruction patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152(4S):35S-40S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000010354

8. Chang DW, Wang B, Robb GL, et al. Effect of obesity on flap and donor-site complications in free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(5):1640-1648. doi:10.1097/00006534-200004050-00007

9. Chaudhry A, Oliver JD, Vyas KS, Alsubaie SA, Manrique OJ, Martinez-Jorge J. Outcomes analysis of Goldilocks mastectomy and breast reconstruction: a single institution experience of 96 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119(8):1047-1052. doi:10.1002/jso.25465

10. Schwartz JC. Goldilocks mastectomy: a safe bridge to implant-based breast reconstruction in the morbidly obese. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5(6):e1398. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001398

11. Richardson H, Aronowitz JA. Goldilocks mastectomy with bilateral in situ nipple preservation via dermal pedicle. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(4):e1748. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001748

12. Egozi D, Allwies TM, Fishel R, Jacobi E, Lemberger M. Free nipple grafting and nipple sharing in autologous breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(9):e3138. doi:10.1097/gox.0000000000003138

13. Westrick E, Mostovych A, MacDavid J, Simpson A, Wilhelmi BJ. The double donut: a safe and simple option for immediate nipple areolar complex reconstruction in skin-sparing mastectomy patients with contraindications to nipple-sparing mastectomy. Eplasty. 2023;23:e37.

14. Bovill JD, Deldar R, Wang J, Greenwalt I, Fan KL. Modified goldilocks nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate prepectoral implant-based reconstruction: a case report. Gland Surg. 2022;11(5):927-931. doi:10.21037/gs-22-74

15. Setit A, Bela K, Khater A, Elzahaby I, Hossam A, Hamed E. Nipple sparing Goldilocks mastectomy, a new modification of the original technique. Eur J Breast Health. 2023;19(2):172-176. doi:10.4274/ejbh.galenos.2023.2023-2-1

16. Vazquez OA, Yerke Hansen P, Komberg J, Slutsky HL, Becker H. Free nipple graft breast reduction without a vertical incision. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(3):e4167. doi:10.1097/gox.0000000000004167

17. Schwartz JD, Skowronksi PP. Extending the indications for autologous breast reconstruction using a two-stage modified Goldilocks procedure: a case report. Breast J. 2017;23(3):344-347. doi:10.1111/tbj.12737

18. Cao D, Tsangaris TN, Kouprina N, et al. The superficial margin of the skin-sparing mastectomy for breast carcinoma: factors predicting involvement and efficacy of additional margin sampling. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(5):1330-1340. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9795-8

19. Griepsma M, de Roy van Zuidewijn DB, Grond AJ, Siesling S, Groen H, de Bock GH. Residual breast tissue after mastectomy: how often and where is it located? Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(4):1260-1266. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3383-x

20. Kimura M, Narui K, Shima H, et al. Development of an invasive ductal carcinoma in a contralateral composite nipple graft after an autologous breast reconstruction: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2020;6(1):203. doi:10.1186/s40792-020-00962-2

21. Basu CB, Wahba M, Bullocks JM, Elledge R. Paget disease of a nipple graft following completion of a breast reconstruction with a nipple-sharing technique. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60(2):144-145. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e31806a592b

22. Rapisarda IF, Cook LJ, Gilani SNSG, Bonomi R. Nipple-sparing skin-reducing mastectomy for women with large and ptotic breasts: a 6-year, single-centre experience with the bipedicled dermal flap approach. Indian J Surg. 2021;83(Suppl 2):446-453. doi:10.1007/s12262-021-02725-1

23. Schwartz JC, Skowronski PP. Total single-stage autologous breast reconstruction with free nipple grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3(12):e587. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000000563