Tracking Sleep Leads to Updated Shift Start Times for Colorado Agency

Scott Coduto, a firefighter/paramedic and field instructor for West Metro Fire Rescue in Lakewood, CO, has a one-hour morning commute to work. The early shift start time and long hours, punctuated by calls, can wreak havoc on his sleep.

Coduto said a lack of rest has a tremendous impact on job performance. “Recalling details of protocols or even recollecting the story from a patient becomes challenging when trying to operate on little rest,” he said. “The constant decision of do I go work out and stay healthy or should I go take a nap to catch up on sleep or try to stay ahead of the anticipated sleep loss is a very real concern to me every shift.”

As it is with many others in emergency medicine.

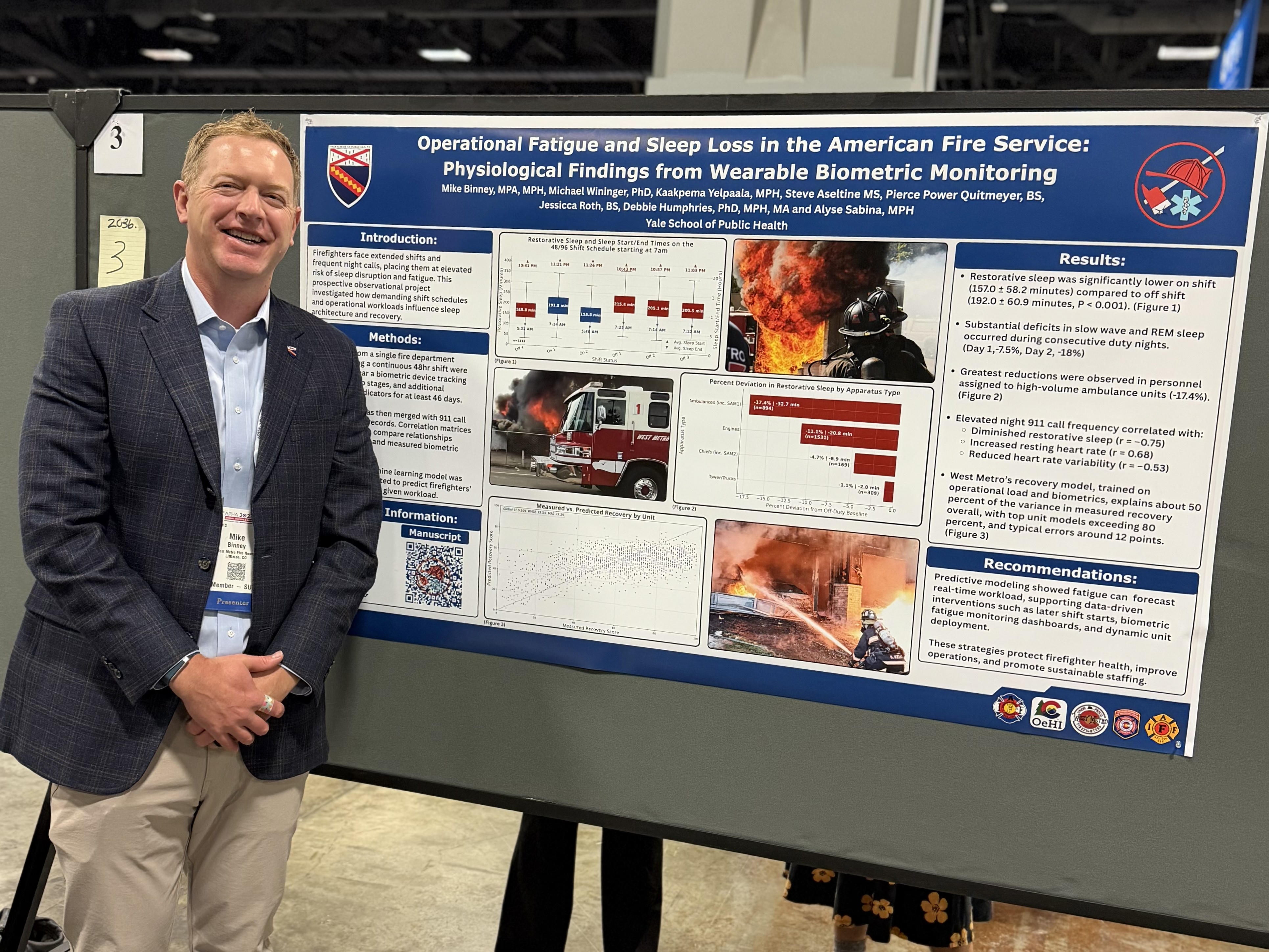

Mike Binney, assistant chief, District 1, C-Shift, noted agencies nationwide have different shift schedules and people have strong opinions about what's best. “There’s not one schedule that fits all,” he said. “The schedules they develop are more about balancing the needs of the labor group, what the city or district can afford and how they want to prioritize.”

Three years ago, Binney needed to complete a project while working on his master’s degree in public health-informatics at Yale School of Public Health. He heard about the daughter of one of the fire-rescue chiefs who uses the WHOOP fitness tracker in her professional cycling. Binney thought it would be an opportunity to measure something that hadn’t been measured before.

Binney teamed up with the Colorado Office of eHealth Innovation, the International Association of Firefighters, the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention & Control, and the Colorado Professional Firefighter Association for funding and other support for a sleep study.

A pilot study compared crew members on shifts to administrative employees who volunteered to participate. The WHOOP was placed on 166 people, with data measured in the background. There was a significant difference between the two groups.

The study showed rescue workers averaged about six hours of sleep each day on a 48-hour shift, with the 7 a.m. start time compelling them to wake up more than an hour earlier than their natural sleep cycle on their shifts’ first and last days. Overnight calls showed a precipitous drop in recovery metrics or heart rate variability.

Getting the right amount of sleep during a 48-hour shift be difficult, not only at stations that see a larger number of calls, but at every station. Crew members lose sleep in constant anticipation.

Coduto said common sleep habits he notices among crews includes a routine of staying up later than normal waiting for the inevitable call. Additionally, crew members can’t get back to sleep after a night call and decide to stay up, further contributing to sleep deprivation.

“Despite having good nights of sleep at work, crews often feel tired going home and need a day of rest to recover from work,” Coduto said. “This is directly contributed to always having to feel ready while at work and some restless nights.”

The study primarily focused on sleep as it could be tied back to operational data.

“We had everyone's information while they were not at work, so we had good naturalistic data of what people do on their days off and how that impacts their recovery,” Binney said.

West Metro Fire Rescue was able to isolate the lowest 25% of baseline sleepers, then follow them across six months of using the WHOOP.

“We were able to measure an increase in their sleep efficiency and their slow wave sleep, so we validated using this tool as a wellness device as well as collecting the data,” Binney said. “It’s a balance between just doing some nerdy data science project and actually finding something that will help people improve at least one domain in their life. We were able to consider using this within our Employee Assistance Program if somebody comes to our group and says they’re having trouble sleeping.”

As a result of the study, shift start times have been changed to 9 a.m. Union members passed the shift change start time by a wide margin.

West Metro Fire Rescue’s study has been picked up by Joel M. Billings, PhD, an assistant professor at Embry‑Riddle Aeronautical University, Dr. Brittany Hollerback, and Sara Jahnke, PhD, director and senior scientist with the Center for Fire, Rescue & EMS Health Research at the National Development & Research Institutes–USA.

“They’re two of the prominent sleep researchers in this space,” Binney said. “They're comparing to our baseline data and adding in questions like how the families feel and how have other things changed in a crew member’s life since we transitioned (the hours).”

Binney noted more agencies nationwide are starting to examine shift hours. News reports show similar strategies in Lake County, Florida; Greenville, North Carolina; and Plano, Texas, among others.

“What we’ve learned from the study is there is a better way we can manipulate the hours within the day to not artificially take sleep opportunity away from people just because we've always done it this way,” he added. “I was on a very busy ambulance for a long time. It was almost like a joke—as soon as you made your bed, you knew you were going to get a call and as soon as you laid down, you would just lay there and think ‘any second that red light in the room is going to light up and we're going to be off again. You don’t let your guard down.”

The study has measured how much deep sleep people get at work versus at home, showing that even subconsciously, people's bodies and minds aren't able to fully slow down when they're on duty. Without enough sleep and the right types of sleep, emergency medicine crew members are at higher risk for metabolic issues and cancer.

“The most important sleep people get from a cognitive perspective is the sleep between 4 a.m. and 8 a.m., depending on the person,” Binney said. “That’s where a lot of REM sleep comes in. Part of the driving factor of why we selected a 9 a.m. start time was yes, there'll be calls, but there are calls everywhere and anywhere at any given time. We’re trying to use our data to find a window in which we can still do shift change that's not waking people up earlier than they need to be up on both ends of their commute and their time to go home.”

While a lack of good sleep can affect job performance, Binney noted “even though our sample size is huge, we're collecting the information in the background to see if there is a higher likelihood of vehicle accidents. We have it well built out in our quality management platform that we'll be able to see during the 48-hour period if there is a relationship between those things, which don’t happen often. Everybody has anecdotal stuff of ‘I was so tired, I don't remember driving home’. Even across three years, we don't have enough information to tie directly any of that together.”

The next frontier is understanding not just the first responders’ biodata, but the periphery of the unintended benefits and costs of starting later, Binney said.

Binney said the data is owned by the union, differentiating the project form others, and addressing data privacy concerns. Crew members don’t want someone from management or the department be able to see what they’re doing at any given time based on a fitness tracker.

“It’s not an open records request thing, allowing the union to be selective on who they share the biodata with for research purposes,” Binney said.

Another benefit of a later start time is that crew members who have relied on caffeine to stay alert during long shifts may see a reduced dependence on it.

“It also doesn't help that the hospitals have cases of energy drinks,” Binney said. “When you drop off a patient, it's almost like a Pavlovian response—drop off a patient, get an energy drink. That’s a concern.”

Coduto notes his own caffeine consumption is higher while he’s at work to provide the energy to do his job. “On my days off, I either need to maintain the same levels of consumption to keep up with demands of family and life or I have to detox from caffeine for a couple of days, which comes at the cost of not being very productive,” he said. “I personally use the cancer risk as motivation to stay fit and not overeat, while balancing my caffeine and sleep habits as best as I can.”

Crew members will continue to wear the sleep tracking devices for several months under the new schedule for making comparisons; the agency has a contract with WHOOP through the end of the year.

“Trying to stick to the scientific method, I think we should remain curious and as we collect the information,” Binney said. “We’re also going to tie in that qualitative information, present it back to our members and be able to say, ‘here was the change. If this was so much of a pain in your home, maybe it's not worth it and we need to look at something completely different. I also want to avoid that we created a project looking for a solution that we reverse engineered.

“I’ve tried to stay far away from the policy implementation side, where my role in this project is to just create a clean data set and not let any biases interfere with its interpretation or implementation so I can give an honest and data-centered product to our administrative staff so they can think about all the unintended consequences.”

Binney advises other agencies interested in embarking on a similar mission to consider data privacy and incorporate funding and partnering with research universities and local labor groups. “Maybe then we'll start to come towards some sort of evidence-based consensus on the safest and healthiest way to do what we do,” Binney said. “All of this blends into the larger wellness umbrella of what we're doing, why we do this job, and how we can help the people who are doing the job.”

Coduto said with the later shift start time, he still plans to leave his house before 5 a.m. to get to Denver, using the extra time to work out or study before shift. His commute home falls after peak traffic hours, enabling him to get home to have lunch with his son. Coduto said he is pleased to be part of a study collecting scientific data within the department to drive best practice policies and procedures—how shift change time data will compare to previous collected data and real-time benefits, including considering an even later start time.

“Having real scientific data to prove the benefits is incredibly valuable and gives actual scientific weight to what we are doing,” he added. “I hope it can help prevent more of the health risk of the profession and allow people to retire healthy and happy from this career.”