Beyond the Skill Sheet: From Memorization to Mastery

This may make some EMS instructors uncomfortable, but students must memorize their skill sheets. Many educators fear memorization creates “cookbook medics,” which often leads them to discourage it. Imagine a classroom where students perform every skill flawlessly yet freeze the moment a situation strays from the script. However, I would argue the opposite: when used intentionally, memorization is not a barrier to critical thinking—it’s the foundation that allows it to develop.

Let’s compare learning skill sheets to cooking. The first time you try a new recipe, you follow the steps exactly. The second time, you adjust the seasoning to taste. A few times later, you might swap out proteins or make other changes, and eventually, you end up with your own dish. Learning skills should follow the same pattern. Students need to memorize the skill sheets, then explore ways to adjust wording and steps to give the skill their own flavor. After mastering this, they learn to edit with purpose and develop their own flow. The final step follows the original structure, but each outcome looks slightly different.

Memorizing the Steps

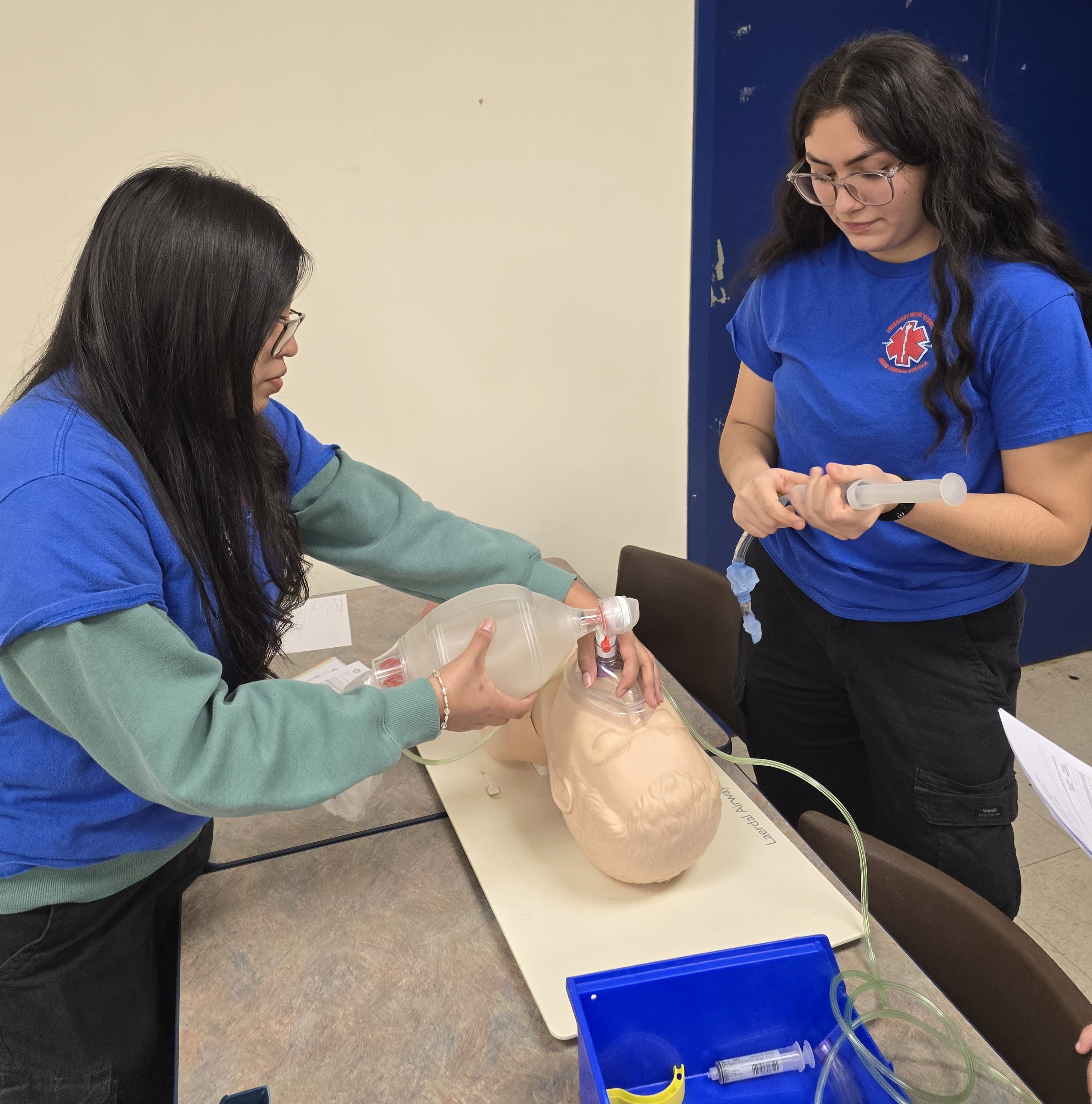

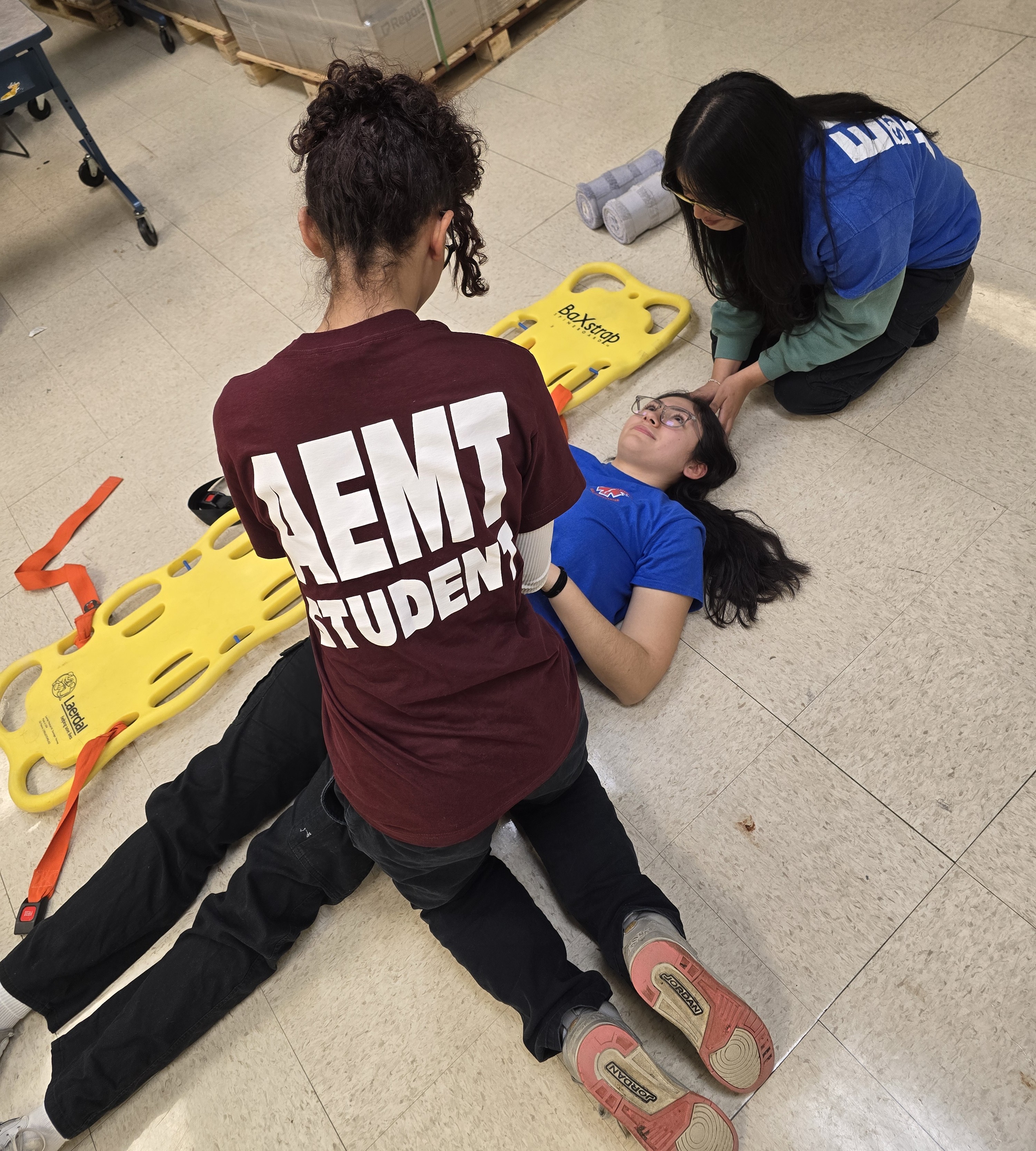

The first step is memorization. We implement this through “I do, we do, you do” instruction, guiding students step by step in small groups or individually. Students are quizzed and participate in hands-on skill practice sessions to reinforce accuracy and sequencing. Instructors can also provide a skills challenge through the “Ring of Fire” exercise. This fast, controlled, high-pressure activity has students form a circle while one student performs as many steps of a newly learned skill as possible from memory. The rest of the class must actively track each step mentally, preparing to continue the skill when it becomes their turn. When the performing student misses a step or makes an error, the next student immediately begins again at step one. This structure promotes focused observation, repeated mental rehearsal, and early exposure to performance pressure without overwhelming learners. As students gain proficiency, the activity can later evolve into sequential or popcorn-style performance to reinforce flow, endurance, and confidence.

Collectively, these structured practice activities shift learning from passive observation to active, simulated experience, aligning with the core principles of Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience.1 Once memorization is solid, students are ready to personalize the skill steps and move to the next phase.

Personalizing the Recipe

In the personalizing phase, students take the steps they’ve memorized and start to season them, adjusting for their own style while keeping the core recipe intact. Some students rely heavily on medical terminology, explaining each step exactly as written. Others combine steps into single sentences and use plain English. Both approaches are valid if the outcome meets clinical standards. Students continue this cycle throughout skill development, learning to personalize without losing accuracy. With personalization in place, they can transition into the modifying phase.

In this phase, students learn to think, not just perform. They combine multiple skill sheets into realistic scenarios, multitask, prioritize steps, and explain the reasoning behind their choices. They also troubleshoot basic problems that arise during skills practice. During this phase, allowing students to struggle, rather than immediately stepping in to help, is crucial for growth. Critical thinking begins to flourish, supported by purposeful, repetitive practice and instructor feedback.

This approach is backed by research. K. Anders Ericsson’s 1993 study "The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance" emphasized that skill development depends on deliberate practice, not mere repetition.2 In the classroom, structured opportunities for practice, feedback, and refinement provide exactly this scaffold for growth.

Owning the Recipe

The final phase is creating their own recipe. Students move from following instructions to fully owning their skills. Their methods reflect training, but each student executes skills uniquely. This ensures preparation for the unpredictable realities of the field. No-win scenarios are particularly valuable at this stage. Students must respond when treatments fail or plans collapse. They also need to explain and defend every action. Even a short timeout to justify a field diagnosis reinforces both practical skills and the knowledge required for the NREMT.

By this stage, students can handle most real-world problems. How do they respond if oxygen runs out, suction is broken, or when another shift fails to restock the bag? They must think critically and adapt on the fly. Debriefing evolves from a basic review to a deep discussion. After each scenario, ask: Why did you do that? Why not take a different approach? How would your plan change under different conditions? Bring the entire class into the discussion. In EMS and fire culture, crews often gather around the kitchen table to reflect on calls, and this informal exchange is where much learning occurs. Bringing this tradition into the classroom reinforces skills, critical thinking, and comfort with giving and receiving constructive feedback.

This kitchen table debriefing directly applies to William C. McGaghie’s article A critical review of simulation-based medical education research: 2003–2009, which identified 12 features to maximize skill and knowledge retention.3 In practice, this single activity incorporates multiple features: students give and receive immediate feedback, engage in deliberate practice by repeating scenarios, measure outcomes through timed skills or success criteria, refine mastery through repeated debriefs, and simulate high-stakes decision-making, all reinforcing the progression from memorization to mastery.

This entire model also aligns with David Allen Kolb’s Learning Cycle described in Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) or Experiential Learning Cycle.4 Students begin with concrete experience by following the recipe. They then reflect, modify, and actively experiment, gradually mastering skills while building critical thinking. This cycle continues beyond the classroom, reinforcing lifelong learning necessary for effective field performance.

Memorization is not the enemy when used as a stepping stone. Just as we teach students to memorize signs and symptoms of diseases while reminding them, “The patient may present differently. They didn’t read the textbook,” we can teach skills the same way. Guiding students from memorization to mastery helps them think critically while building confidence and competence.

Next time you teach skills, let your students follow the recipe, taste test their skills, and gradually add their own flavor. By doing so, you prepare them not just to pass exams, but to thrive in the unpredictable realities of the field. Memorization becomes the foundation, and mastery and critical thinking follow naturally.

References

1. Dale, E. (1969). Audiovisual methods in teaching (3rd ed.). Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

2. Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

3. Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

4. McGaghie, W. C., Issenberg, S. B., Petrusa, E. R., & Scalese, R. J. (2010). A critical review of simulation-based medical education research: 2003–2009. Medical Education, 44(1), 50–63.

About the Author

Ryan Cogdill is an EMS educator, innovator, and mentor shaping the next generation of prehospital providers. He leads the nation’s first high school AEMT capstone program and engages students in promoting school and community safety through initiatives like HeartSafe School and Survive Alive House. Using technology and flipped, mastery-based learning, he maximizes classroom time for hands-on skills and ensures students achieve deep understanding. He also continues hands-on work as a firefighter and on a rural county ambulance, blending classroom instruction, field experience, and student-driven community initiatives to make EMS education practical, engaging, and impactful.